Introduction: Cerber ransomware

Researchers at Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) received reports of the Cerber ransomware being deployed onto servers running the Confluence application via the CVE-2023-22518 exploit. [1] There is a large amount of coverage on the Windows variant, however there is very little about the Linux variant. This blog will discuss an analysis of the Linux variant.

Cerber emerged and was at the peak of its activity around 2016, and has since only occasional campaigns, most recently targeting the aforementioned Confluence vulnerability. It consists of three highly obfuscated C++ payloads, compiled as a 64-bit Executable and Linkable Format (ELF, the format for executable binary files on Linux) and packed with UPX. UPX is a very common packer used by many threat actors. It allows the actual program code to be stored encoded in the binary, and at runtime extracted into memory and executed (“unpacked”). This is done to prevent software from scanning the payload and detecting the malware.

Pure C++ payloads are becoming less common on Linux, with many threat actors now employing newer programming languages such as Rust or Go. [2] This is likely due to the Cerber payload first being released almost 8 years ago. While it will have certainly received updates, the language and tooling choices are likely to have stuck around for the lifetime of the payload.

Initial access

Cado researchers observed instances of the Cerber ransomware being deployed after a threat actor leveraged CVE-2023-22518 in order to gain access to vulnerable instances of Confluence [3]. It is an improper authorization vulnerability that allows an attacker to reset the Confluence application and create a new administrator account using an unprotected configuration restore endpoint used by the setup wizard.

[19/Mar/2024:15:57:24 +0000] - http-nio-8090-exec-10 13.40.171.234 POST /json/setup-restore.action?synchronous=true HTTP/1.1 302 81796ms - - python-requests/2.31.0

[19/Mar/2024:15:57:24 +0000] - http-nio-8090-exec-3 13.40.171.234 GET /json/setup-restore-progress.action?taskId= HTTP/1.1 200 108ms 283 - python-requests/2.31.0 Once an administrator account is created, it can be used to gain code execution by uploading & installing a malicious module via the admin panel. In this case, the Effluence web shell plugin is directly uploaded and installed, which provides a web UI for executing arbitrary commands on the host.

The threat actor uses this web shell to download and run the primary Cerber payload. In a default install, the Confluence application is executed as the “confluence” user, a low privilege user. As such, the data the ransomware is able to encrypt is limited to files owned by the confluence user. It will of course succeed in encrypting the datastore for the Confluence application, which can store important information. If it was running as a higher privilege user, it would be able to encrypt more files, as it will attempt to encrypt all files on the system.

Primary payload

Summary of payload:

- Written in C++, highly obfuscated, and packed with UPX

- Serves as a stager for further payloads

- Uses a C2 server at 45[.]145[.]6[.]112 to download and unpack further payloads

- Deletes itself off disk upon execution

The primary payload is packed with UPX, just like the other payloads. Its main purpose is to set up the environment and grab further payloads in order to run.

Upon execution it unpacks itself and tries to create a file at /var/lock/0init-ld.lo. It is speculated that this was meant to serve as a lock file and prevent duplicate execution of the ransomware, however if the lock file already exists the result is discarded, and execution continues as normal anyway.

It then connects to the (now defunct) C2 server at 45[.]145[.]6[.]112 and pulls down the secondary payload, a log checker, known internally as agttydck. It does this by doing a simple GET /agttydcki64 request to the server using HTTP and writing the payload body out to /tmp/agttydck.bat. It then executes it with /tmp and ck.log passed as arguments. The execution of the payload is detailed in the next section.

Once the secondary payload has finished executing, the primary payload checks if the log file at /tmp/ck.log it wrote exists. If it does, it then proceeds to delete itself and agttydcki64 from the disk. As it is still running in memory, it then downloads the encryptor payload, known internally as agttydcb, and drops it at /tmp/agttydcb.bat. The packing on this payload is more complex. The file command reports it as a DOS executable and the bat extension would imply this as well. However, it does not have the correct magic bytes, and the high entropy of the file suggests that it is potentially encoded or encrypted. Indeed, the primary payload reads it in and then writes out a decoded ELF file back using the same stream, overwriting the content. It is unclear the exact mechanism used to decode agttydcb. The primary payload then executes the decoded agttydcb, the behavior of which is documented in a later section.

2283 openat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/agttydcb.bat", O_RDWR) = 4

…

2283 read(4, "\353[\254R\333\372\22,\1\251\f\235 'A>\234\33\25E3g\335\0252\344vBg\177\356\321"..., 450560) = 450560

…

2283 lseek(4, 0, SEEK_SET) = 0

2283 write(4, "\177ELF\2\1\1\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\2\0>\0\1\0\0\0X\334F\0\0\0\0\0"..., 450560) = 450560

…

2283 close(4) = 0 Truncated strace output for the decoding process

Log check payload - agttydck

Summary of payload:

- Written in C++, highly obfuscated, and packed with UPX

- Tries to write the phrase “success” to a given file passed in arguments

- Likely a check for sandboxing, or to check the permission level of the malware on the system

The log checker payload, agttydck, likely serves as a permission checker. It is a very simple payload and was easy to analyze statically despite the obfuscation. Like the other payloads, it is UPX packed.

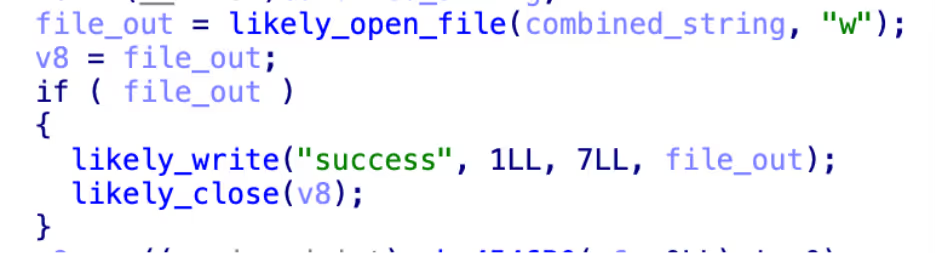

When run, it concatenates each argument passed to it and delimits with forward slashes in order to obtain a full path. In this case, it is passed /tmp and ck.log, which becomes /tmp/ck.log. It then tries to open this file in write mode, and if it succeeds writes the word “success” and returns 0. If it does not succeed, it returns 1.

The purpose of this check isn’t exactly clear. It could be to check if the tmp directory is writable and that it can write, which may be a check for if the system is too locked down for the encryptor to work. Given the check is run in a process separate to the primary payload, it could also be an attempt to detect sandboxes that may not handle files correctly, resulting in the primary payload not being told about the file created by the child.

Encryptor - agttydck

Summary of payload:

- Written in C++, highly obfuscated, and packed with UPX

- Writes log file /tmp/log.0 on start and /tmp/log.1 on completion, likely for debugging

- Walks the root directory looking for directories it can encrypt

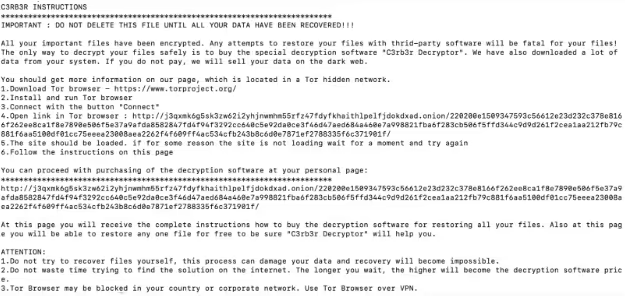

- Writes a ransom note to each directory

- Overwrites all files in directory with their encrypted content and adds a .L0CK3D extension

The encryptor, agttydcb, achieves the goal of the ransomware, which is to encrypt files on the filesystem. Like the other payloads, it is UPX packed and written with heavily obfuscated C++. Upon launch, it deletes itself off disk so as to not leave any artefacts. It then creates a file at /tmp/log.0, but with no content. As it creates a second file at /tmp/log.1 (also with no content) after encryption finishes, it is possible these were debug markers that the attacker mistakenly left in.

The encryptor then spawns a new thread to do the actual encryption. The payload attempts to write a ransom note at /<directory>/read-me3.txt. If it succeeds, it will walk all files in the directory and attempt to encrypt them. If it fails, it moves on to the next directory. The encryptor chooses to pick which directories to encrypt by walking the root file system. For example, it will try to encrypt /usr, and then /var, etc.

When it has identified a file to encrypt, it opens a read-write file stream to the file and reads in the entire file. It is then encrypted in memory before it seeks to the start of the stream and writes the encrypted data, overwriting the file content, and rendering the file fully encrypted. It then renames the file to have the .L0CK3D extension. Rewriting the same file instead of making a new file and deleting the old one is useful on Linux as directories may be set to append only, preventing the outright deletion of files. Rewriting the file may also rewrite the data on the underlying storage, making recovery with advanced forensics also impossible.

2290 openat(AT_FDCWD, "/home/ubuntu/example", O_RDWR) = 6

…

2290 read(6, "file content"..., 3691) = 3691

…

2290 write(6, "\241\253\270'\10\365?\2\300\304\275=\30B\34\230\254\357\317\242\337UD\266\362\\\210\215\245!\255f"

..., 3691) = 3691

2290 close(6) = 0

2290 rename("/home/ubuntu/example", "/home/ubuntu/example.L0CK3D") = 0 Truncated strace of the encryption process

Once this finishes, it tries to delete itself again (which fails as it already deleted itself) and creates /tmp/log.1. It then gracefully exits. Despite the ransom note claiming the files were exfiltrated, Cado researchers did not observe any behavior that showed this.

Conclusion

Cerber is a relatively sophisticated, albeit aging, ransomware payload. While the use of the Confluence vulnerability allows it to compromise a large amount of likely high value systems, often the data it is able to encrypt will be limited to just the confluence data and in well configured systems this will be backed up. This greatly limits the efficacy of the ransomware in extracting money from victims, as there is much less incentive to pay up.

IoCs

The payloads are packed with UPX so will match against existing UPX Yara rules.

Hashes (sha256)

cerber_primary 4ed46b98d047f5ed26553c6f4fded7209933ca9632b998d265870e3557a5cdfe

agttydcb 1849bc76e4f9f09fc6c88d5de1a7cb304f9bc9d338f5a823b7431694457345bd

agttydck ce51278578b1a24c0fc5f8a739265e88f6f8b32632cf31bf7c142571eb22e243

IPs

C2 (Defunct) 45[.]145[.]6[.]112

References

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)