An integral part of cybersecurity is anomaly detection, which involves identifying unusual patterns or behaviors in network traffic that could indicate malicious activity, such as a cyber-based intrusion. However, attribution remains one of the ever present challenges in cybersecurity. Attribution involves the process of accurately identifying and tracing the source to a specific threat actor(s).

Given the complexity of digital networks and the sophistication of attackers who often use proxies or other methods to disguise their origin, pinpointing the exact source of a cyberattack is an arduous task. Threat actors can use proxy servers, botnets, sophisticated techniques, false flags, etc. Darktrace’s strategy is rooted in the belief that identifying behavioral anomalies is crucial for identifying both known and novel threat actor campaigns.

The ShadowPad cluster

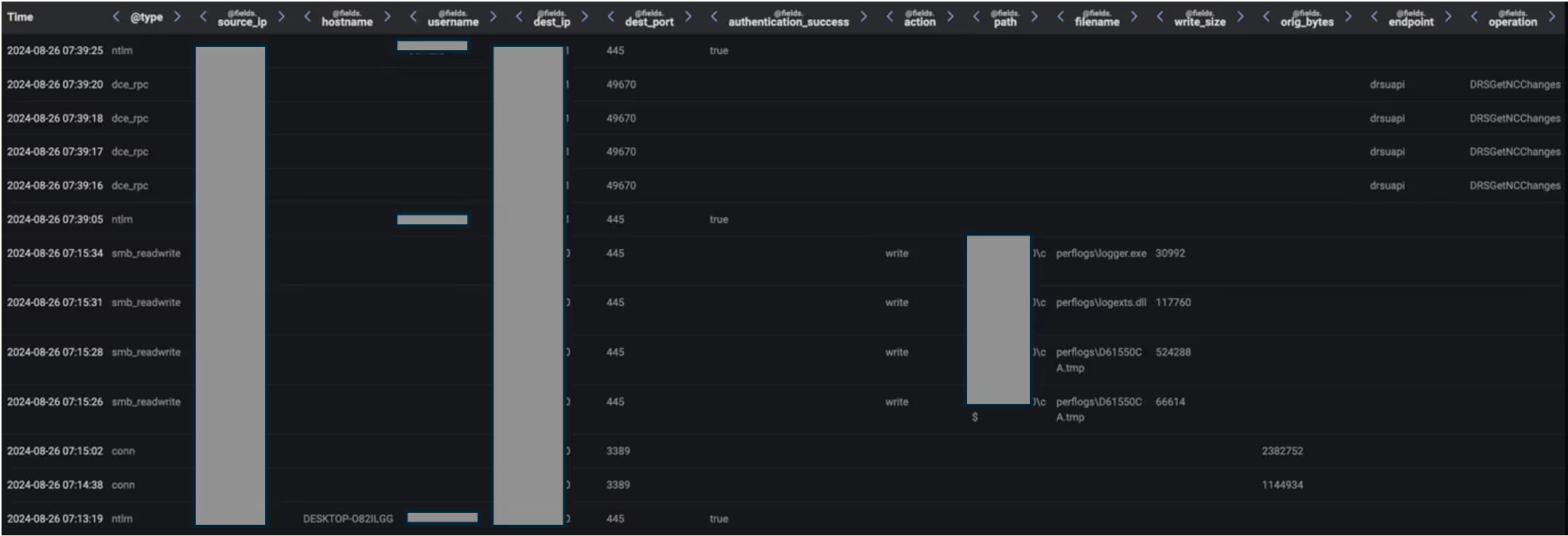

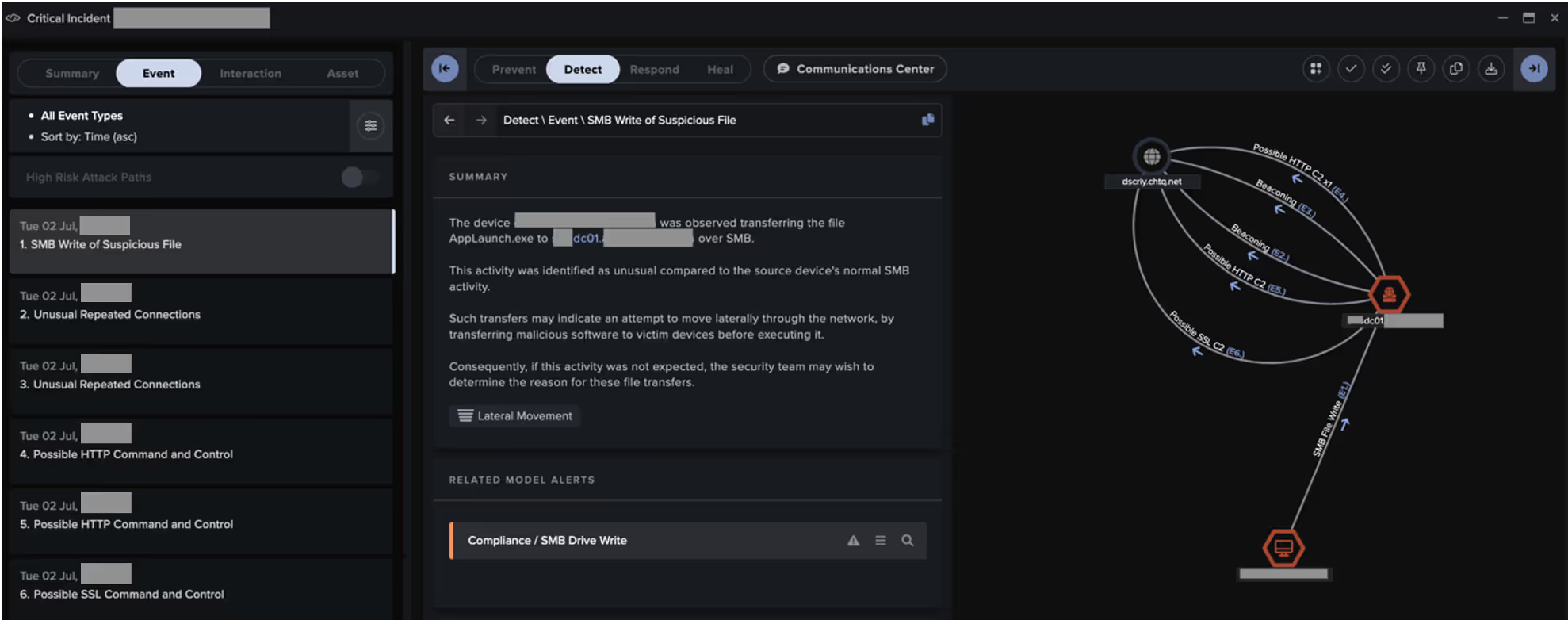

Between July 2024 and November 2024, Darktrace observed a cluster of activity threads sharing notable similarities. The threads began with a malicious actor using compromised user credentials to log in to the target organization's Check Point Remote Access virtual private network (VPN) from an attacker-controlled, remote device named 'DESKTOP-O82ILGG'. In one case, the IP from which the initial login was carried out was observed to be the ExpressVPN IP address, 194.5.83[.]25. After logging in, the actor gained access to service account credentials, likely via exploitation of an information disclosure vulnerability affecting Check Point Security Gateway devices. Recent reporting suggests this could represent exploitation of CVE-2024-24919 [27,28]. The actor then used these compromised service account credentials to move laterally over RDP and SMB, with files related to the modular backdoor, ShadowPad, being delivered to the ‘C:\PerfLogs\’ directory of targeted internal systems. ShadowPad was seen communicating with its command-and-control (C2) infrastructure, 158.247.199[.]185 (dscriy.chtq[.]net), via both HTTPS traffic and DNS tunneling, with subdomains of the domain ‘cybaq.chtq[.]net’ being used in the compromised devices’ TXT DNS queries.

![Event Log data showing a DC making DNS queries for subdomains of ‘cbaq.chtq[.]net’ to 158.247.199[.]185 after receiving SMB and RDP connections from the VPN-connected device, DESKTOP-O82ILGG.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/67d1dbda2020b168dc1d83c2_Screenshot%202025-03-12%20at%2012.07.41%E2%80%AFPM.avif)

Darktrace observed these ShadowPad activity threads within the networks of European-based customers in the manufacturing and financial sectors. One of these intrusions was followed a few months later by likely state-sponsored espionage activity, as detailed in the investigation of the year in Darktrace’s Annual Threat Report 2024.

[related-resource]

Related ShadowPad activity

Additional cases of ShadowPad were observed across Darktrace’s customer base in 2024. In some cases, common C2 infrastructure with the cluster discussed above was observed, with dscriy.chtq[.]net and cybaq.chtq[.]net both involved; however, no other common features were identified. These ShadowPad infections were observed between April and November 2024, with customers across multiple regions and sectors affected. Darktrace’s observations align with multiple other public reports that fit the timeframe of this campaign.

Darktrace has also observed other cases of ShadowPad without common infrastructure since September 2024, suggesting the use of this tool by additional threat actors.

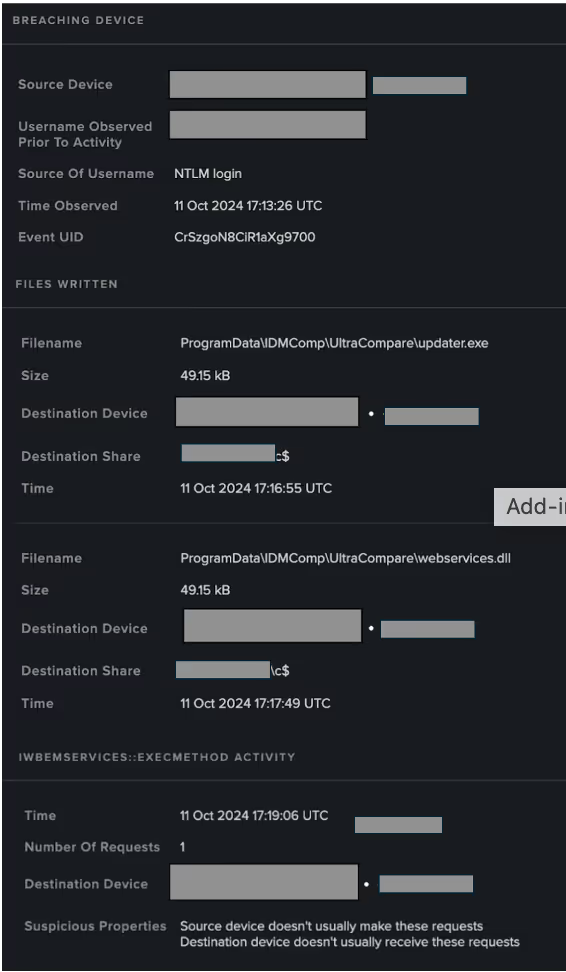

The data theft thread

One of the Darktrace customers impacted by the ShadowPad cluster highlighted above was a European manufacturer. A distinct thread of activity occurred within this organization’s network several months after the ShadowPad intrusion, in October 2024.

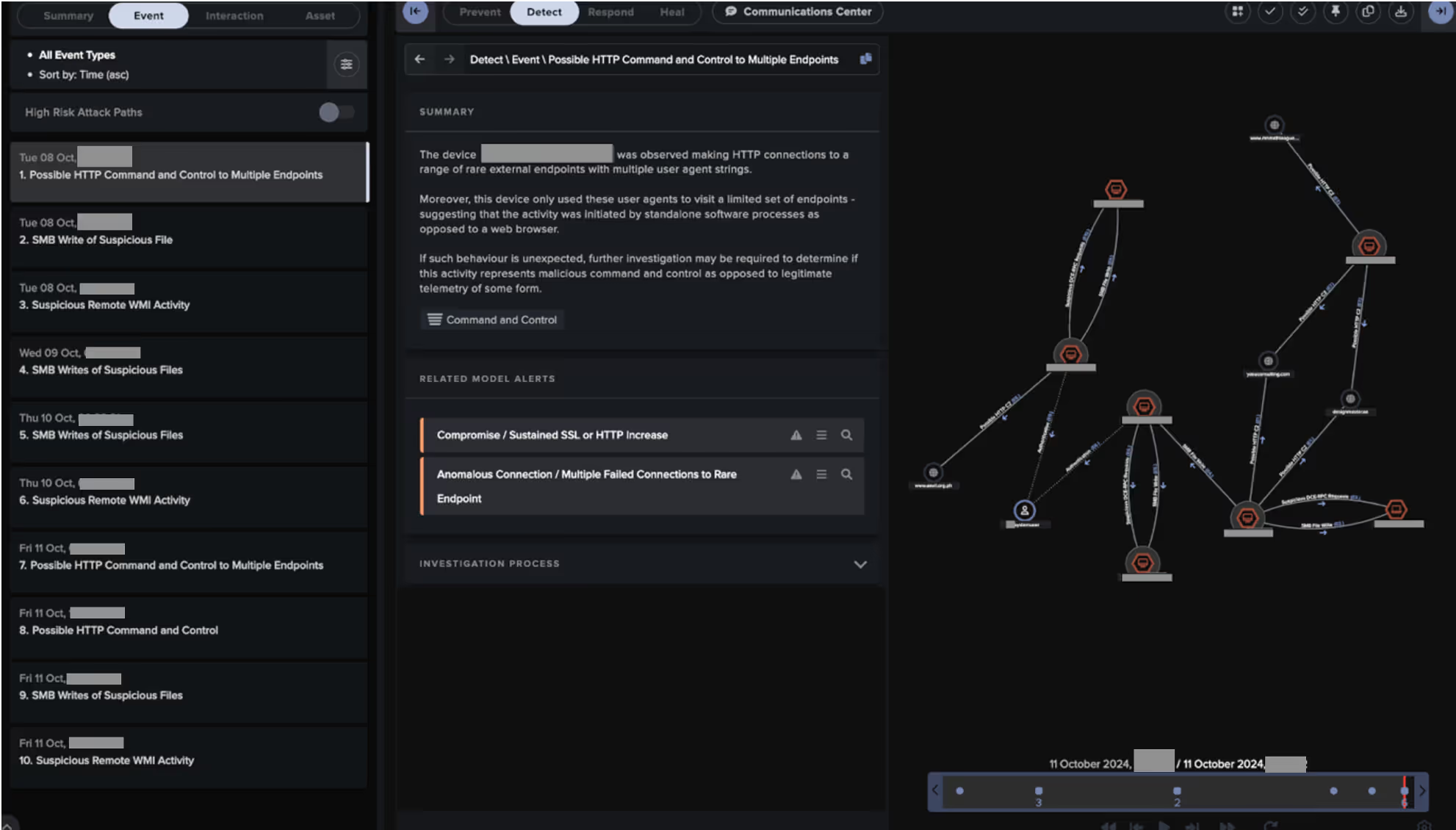

The thread involved the internal distribution of highly masqueraded executable files via Sever Message Block (SMB) and WMI (Windows Management Instrumentation), the targeted collection of sensitive information from an internal server, and the exfiltration of collected information to a web of likely compromised sites. This observed thread of activity, therefore, consisted of three phrases: lateral movement, collection, and exfiltration.

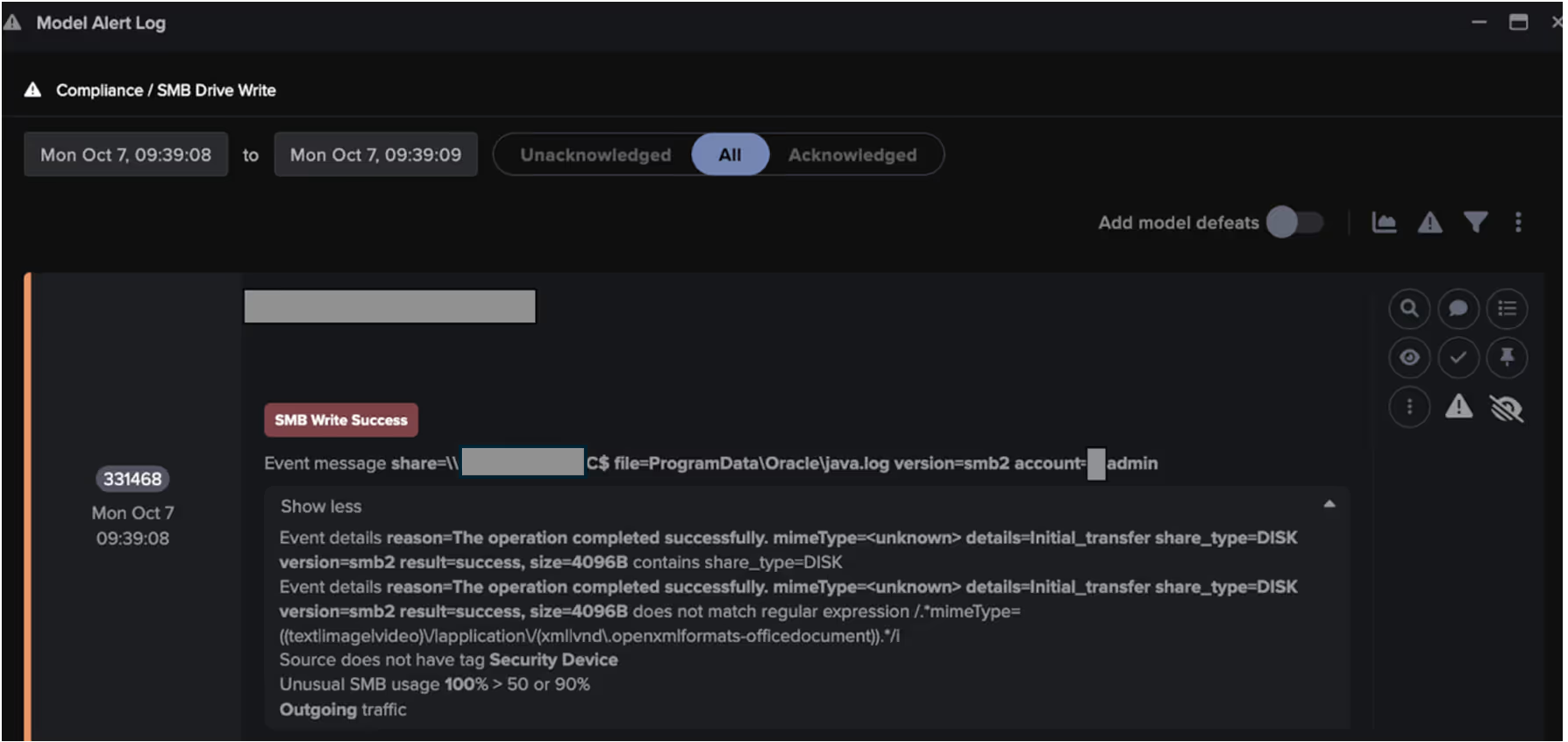

The lateral movement phase began when an internal user device used an administrative credential to distribute files named ‘ProgramData\Oracle\java.log’ and 'ProgramData\Oracle\duxwfnfo' to the c$ share on another internal system.

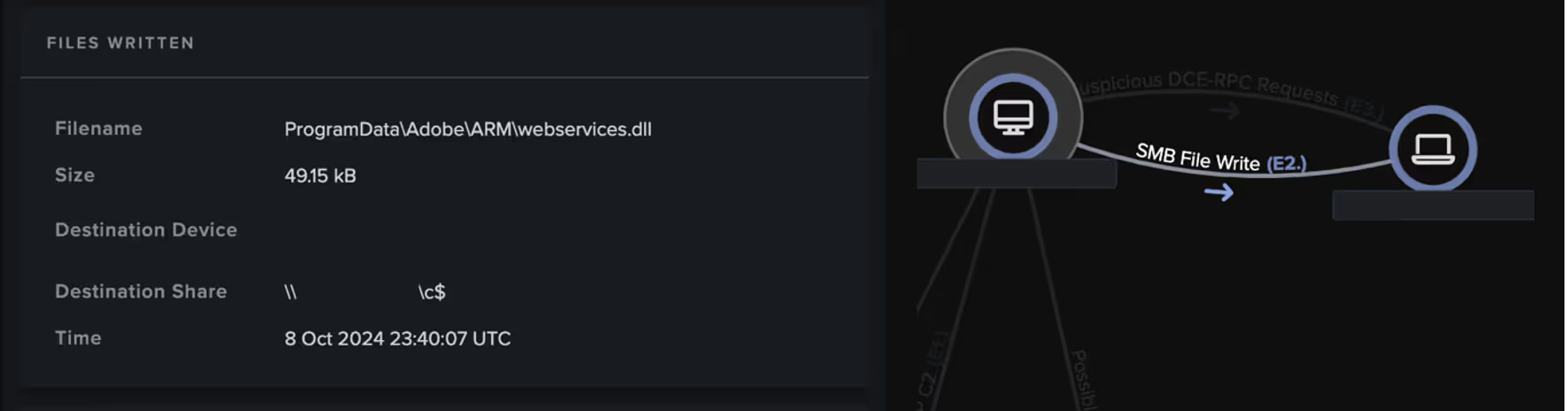

Over the next few days, Darktrace detected several other internal systems using administrative credentials to upload files with the following names to the c$ share on internal systems:

ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\webservices.dll

ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\wksprt.exe

ProgramData\Oracle\Java\wksprt.exe

ProgramData\Oracle\Java\webservices.dll

ProgramData\Microsoft\DRM\wksprt.exe

ProgramData\Microsoft\DRM\webservices.dll

ProgramData\Abletech\Client\webservices.dll

ProgramData\Abletech\Client\client.exe

ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\rzrmxrwfvp

ProgramData\3Dconnexion\3DxWare\3DxWare.exe

ProgramData\3Dconnexion\3DxWare\webservices.dll

ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\updater.exe

ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\webservices.dll

ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\imtrqjsaqmm

The threat actor appears to have abused the Microsoft RPC (MS-RPC) service, WMI, to execute distributed payloads, as evidenced by the ExecMethod requests to the IWbemServices RPC interface which immediately followed devices’ SMB uploads.

Several of the devices involved in these lateral movement activities, both on the source and destination side, were subsequently seen using administrative credentials to download tens of GBs of sensitive data over SMB from a specially selected server. The data gathering stage of the threat sequence indicates that the threat actor had a comprehensive understanding of the organization’s system architecture and had precise objectives for the information they sought to extract.

Immediately after collecting data from the targeted server, devices went on to exfiltrate stolen data to multiple sites. Several other likely compromised sites appear to have been used as general C2 infrastructure for this intrusion activity. The sites used by the threat actor for C2 and data exfiltration purport to be sites for companies offering a variety of service, ranging from consultancy to web design.

At least 16 sites were identified as being likely data exfiltration or C2 sites used by this threat actor in their operation against this organization. The fact that the actor had such a wide web of compromised sites at their disposal suggests that they were well-resourced and highly prepared.

![Darktrace model alert highlighting an internal device slowly exfiltrating data to the external endpoint, yasuconsulting[.]com.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/67d1dd09fe9cf54a67c48f13_Screenshot%202025-03-12%20at%2012.14.04%E2%80%AFPM.avif)

![Darktrace model alert highlighting an internal device downloading nearly 1 GB of data from an internal system just before uploading a similar volume of data to another suspicious endpoint, www.tunemmuhendislik[.]com](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/67d1dd45f3743ebe06d81d89_Screenshot%202025-03-12%20at%2012.14.46%E2%80%AFPM.avif)

Cyber AI Analyst spotlight

As shown in the above figures, Cyber AI Analyst’s ability to thread together the different steps of these attack chains are worth highlighting.

In the ShadowPad attack chains, Cyber AI Analyst was able to identify SMB writes from the VPN subnet to the DC, and the C2 connections from the DC. It was also able to weave together this activity into a single thread representing the attacker’s progression.

Similarly, in the data exfiltration attack chain, Cyber AI Analyst identified and connected multiple types of lateral movement over SMB and WMI and external C2 communication to various external endpoints, linking them in a single, connected incident.

These Cyber AI Analyst actions enabled a quicker understanding of the threat actor sequence of events and, in some cases, faster containment.

Attribution puzzle

Publicly shared research into ShadowPad indicates that it is predominantly used as a backdoor in People’s Republic of China (PRC)-sponsored espionage operations [5][6][7][8][9][10]. Most publicly reported intrusions involving ShadowPad are attributed to the China-based threat actor, APT41 [11][12]. Furthermore, Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) recently shared their assessment that ShadowPad usage is restricted to clusters associated with APT41 [13]. Interestingly, however, there have also been public reports of ShadowPad usage in unattributed intrusions [5].

The data theft activity that later occurred in the same Darktrace customer network as one of these ShadowPad compromises appeared to be the targeted collection and exfiltration of sensitive data. Such an objective indicates the activity may have been part of a state-sponsored operation. The tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), artifacts, and C2 infrastructure observed in the data theft thread appear to resemble activity seen in previous Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)-linked intrusion activities [15] [16] [17] [18] [19].

The distribution of payloads to the following directory locations appears to be a relatively common behavior in DPRK-sponsored intrusions.

Observed examples:

C:\ProgramData\Oracle\Java\

C:\ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\

C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\DRM\

C:\ProgramData\Abletech\Client\

C:\ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\

C:\ProgramData\3Dconnexion\3DxWare\

Additionally, the likely compromised websites observed in the data theft thread, along with some of the target URI patterns seen in the C2 communications to these sites, resemble those seen in previously reported DPRK-linked intrusion activities.

No clear evidence was found to link the ShadowPad compromise to the subsequent data theft activity that was observed on the network of the manufacturing customer. It should be noted, however, that no clear signs of initial access were found for the data theft thread – this could suggest the ShadowPad intrusion itself represents the initial point of entry that ultimately led to data exfiltration.

Motivation-wise, it seems plausible for the data theft thread to have been part of a DPRK-sponsored operation. DPRK is known to pursue targets that could potentially fulfil its national security goals and had been publicly reported as being active in months prior to this intrusion [21]. Furthermore, the timing of the data theft aligns with the ratification of the mutual defense treaty between DPRK and Russia and the subsequent accused activities [20].

Darktrace assesses with medium confidence that a nation-state, likely DPRK, was responsible, based on our investigation, the threat actor applied resources, patience, obfuscation, and evasiveness combined with external reporting, collaboration with the cyber community, assessing the attacker’s motivation and world geopolitical timeline, and undisclosed intelligence.

Conclusion

When state-linked cyber activity occurs within an organization’s environment, previously unseen C2 infrastructure and advanced evasion techniques will likely be used. State-linked cyber actors, through their resources and patience, are able to bypass most detection methods, leaving anomaly-based methods as a last line of defense.

Two threads of activity were observed within Darktrace’s customer base over the last year: The first operation involved the abuse of Check Point VPN credentials to log in remotely to organizations’ networks, followed by the distribution of ShadowPad to an internal domain controller. The second operation involved highly targeted data exfiltration from the network of one of the customers impacted by the previously mentioned ShadowPad activity.

Despite definitive attribution remaining unresolved, both the ShadowPad and data exfiltration activities were detected by Darktrace’s Self-Learning AI, with Cyber AI Analyst playing a significant role in identifying and piecing together the various steps of the intrusion activities.

Credit to Sam Lister (R&D Detection Analyst), Emma Foulger (Principal Cyber Analyst), Nathaniel Jones (VP), and the Darktrace Threat Research team.

Appendices

Darktrace / NETWORK model alerts

User / New Admin Credentials on Client

Anomalous Connection / Unusual Admin SMB Session

Compliance / SMB Drive Write

Device / Anomalous SMB Followed By Multiple Model Breaches

Anomalous File / Internal / Unusual SMB Script Write

User / New Admin Credentials on Client

Anomalous Connection / Unusual Admin SMB Session

Compliance / SMB Drive Write

Device / Anomalous SMB Followed By Multiple Model Breaches

Anomalous File / Internal / Unusual SMB Script Write

Device / New or Uncommon WMI Activity

Unusual Activity / Internal Data Transfer

Anomalous Connection / Download and Upload

Anomalous Server Activity / Rare External from Server

Compromise / Beacon to Young Endpoint

Compromise / Agent Beacon (Short Period)

Anomalous Server Activity / Anomalous External Activity from Critical Network Device

Anomalous Connection / POST to PHP on New External Host

Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

Compromise / Sustained TCP Beaconing Activity To Rare Endpoint

Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

Device / Multiple C2 Model Alerts

Anomalous Connection / Data Sent to Rare Domain

Anomalous Connection / Download and Upload

Unusual Activity / Unusual External Data Transfer

Anomalous Connection / Low and Slow Exfiltration

Anomalous Connection / Uncommon 1 GiB Outbound

MITRE ATT&CK mapping

(Technique name – Tactic ID)

ShadowPad malware threads

Initial Access - Valid Accounts: Domain Accounts (T1078.002)

Initial Access - External Remote Services (T1133)

Privilege Escalation - Exploitation for Privilege Escalation (T1068)

Privilege Escalation - Valid Accounts: Default Accounts (T1078.001)

Defense Evasion - Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location (T1036.005)

Lateral Movement - Remote Services: Remote Desktop Protocol (T1021.001)

Lateral Movement - Remote Services: SMB/Windows Admin Shares (T1021.002)

Command and Control - Proxy: Internal Proxy (T1090.001)

Command and Control - Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols (T1071.001)

Command and Control - Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography (T1573.002)

Command and Control - Application Layer Protocol: DNS (T1071.004)

Data theft thread

Resource Development - Compromise Infrastructure: Domains (T1584.001)

Privilege Escalation - Valid Accounts: Default Accounts (T1078.001)

Privilege Escalation - Valid Accounts: Domain Accounts (T1078.002)

Execution - Windows Management Instrumentation (T1047)

Defense Evasion - Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location (T1036.005)

Defense Evasion - Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027)

Lateral Movement - Remote Services: SMB/Windows Admin Shares (T1021.002)

Collection - Data from Network Shared Drive (T1039)

Command and Control - Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols (T1071.001)

Command and Control - Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography (T1573.002)

Command and Control - Proxy: External Proxy (T1090.002)

Exfiltration - Exfiltration Over C2 Channel (T1041)

Exfiltration - Data Transfer Size Limits (T1030)

List of indicators of compromise (IoCs)

IP addresses and/or domain names (Mid-high confidence):

ShadowPad thread

- dscriy.chtq[.]net • 158.247.199[.]185 (endpoint of C2 comms)

- cybaq.chtq[.]net (domain name used for DNS tunneling)

Data theft thread

- yasuconsulting[.]com (45.158.12[.]7)

- hobivan[.]net (94.73.151[.]72)

- mediostresbarbas.com[.]ar (75.102.23[.]3)

- mnmathleague[.]org (185.148.129[.]24)

- goldenborek[.]com (94.138.200[.]40)

- tunemmuhendislik[.]com (94.199.206[.]45)

- anvil.org[.]ph (67.209.121[.]137)

- partnerls[.]pl (5.187.53[.]50)

- angoramedikal[.]com (89.19.29[.]128)

- awork-designs[.]dk (78.46.20[.]225)

- digitweco[.]com (38.54.95[.]190)

- duepunti-studio[.]it (89.46.106[.]61)

- scgestor.com[.]br (108.181.92[.]71)

- lacapannadelsilenzio[.]it (86.107.36[.]15)

- lovetamagotchith[.]com (203.170.190[.]137)

- lieta[.]it (78.46.146[.]147)

File names (Mid-high confidence):

ShadowPad thread:

- perflogs\1.txt

- perflogs\AppLaunch.exe

- perflogs\F4A3E8BE.tmp

- perflogs\mscoree.dll

Data theft thread

- ProgramData\Oracle\java.log

- ProgramData\Oracle\duxwfnfo

- ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\webservices.dll

- ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\wksprt.exe

- ProgramData\Oracle\Java\wksprt.exe

- ProgramData\Oracle\Java\webservices.dll

- ProgramData\Microsoft\DRM\wksprt.exe

- ProgramData\Microsoft\DRM\webservices.dll

- ProgramData\Abletech\Client\webservices.dll

- ProgramData\Abletech\Client\client.exe

- ProgramData\Adobe\ARM\rzrmxrwfvp

- ProgramData\3Dconnexion\3DxWare\3DxWare.exe

- ProgramData\3Dconnexion\3DxWare\webservices.dll

- ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\updater.exe

- ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\webservices.dll

- ProgramData\IDMComp\UltraCompare\imtrqjsaqmm

- temp\HousecallLauncher64.exe

Attacker-controlled device hostname (Mid-high confidence)

- DESKTOP-O82ILGG

References

[1] https://www.kaspersky.com/about/press-releases/shadowpad-how-attackers-hide-backdoor-in-software-used-by-hundreds-of-large-companies-around-the-world

[2] https://media.kasperskycontenthub.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2017/08/07172148/ShadowPad_technical_description_PDF.pdf

[3] https://blog.avast.com/new-investigations-in-ccleaner-incident-point-to-a-possible-third-stage-that-had-keylogger-capacities

[4] https://securelist.com/operation-shadowhammer-a-high-profile-supply-chain-attack/90380/

[5] https://assets.sentinelone.com/c/Shadowpad?x=P42eqA

[6] https://www.cyfirma.com/research/the-origins-of-apt-41-and-shadowpad-lineage/

[7] https://www.csoonline.com/article/572061/shadowpad-has-become-the-rat-of-choice-for-several-state-sponsored-chinese-apts.html

[8] https://global.ptsecurity.com/analytics/pt-esc-threat-intelligence/shadowpad-new-activity-from-the-winnti-group

[9] https://cymulate.com/threats/shadowpad-privately-sold-malware-espionage-tool/

[10] https://www.secureworks.com/research/shadowpad-malware-analysis

[11] https://blog.talosintelligence.com/chinese-hacking-group-apt41-compromised-taiwanese-government-affiliated-research-institute-with-shadowpad-and-cobaltstrike-2/

[12] https://hackerseye.net/all-blog-items/tails-from-the-shadow-apt-41-injecting-shadowpad-with-sideloading/

[13] https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/threat-intelligence/scatterbrain-unmasking-poisonplug-obfuscator

[14] https://www.domaintools.com/wp-content/uploads/conceptualizing-a-continuum-of-cyber-threat-attribution.pdf

[15] https://www.nccgroup.com/es/research-blog/north-korea-s-lazarus-their-initial-access-trade-craft-using-social-media-and-social-engineering/

[16] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2021/01/28/zinc-attacks-against-security-researchers/

[17] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2022/09/29/zinc-weaponizing-open-source-software/

[18] https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/eset-research/lazarus-luring-employees-trojanized-coding-challenges-case-spanish-aerospace-company/

[19] https://blogs.jpcert.or.jp/en/2021/01/Lazarus_malware2.html

[20] https://usun.usmission.gov/joint-statement-on-the-unlawful-arms-transfer-by-the-democratic-peoples-republic-of-korea-to-russia/

[21] https://media.defense.gov/2024/Jul/25/2003510137/-1/-1/1/Joint-CSA-North-Korea-Cyber-Espionage-Advance-Military-Nuclear-Programs.PDF

[22] https://kyivindependent.com/first-north-korean-troops-deployed-to-front-line-in-kursk-oblast-ukraines-military-intelligence-says/

[23] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2024/12/04/frequent-freeloader-part-i-secret-blizzard-compromising-storm-0156-infrastructure-for-espionage/

[24] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2024/12/11/frequent-freeloader-part-ii-russian-actor-secret-blizzard-using-tools-of-other-groups-to-attack-ukraine/

[25] https://www.sentinelone.com/labs/chamelgang-attacking-critical-infrastructure-with-ransomware/

[26] https://thehackernews.com/2022/06/state-backed-hackers-using-ransomware.html/

[27] https://blog.checkpoint.com/security/check-point-research-explains-shadow-pad-nailaolocker-and-its-protection/

[28] https://www.orangecyberdefense.com/global/blog/cert-news/meet-nailaolocker-a-ransomware-distributed-in-europe-by-shadowpad-and-plugx-backdoors

[related-resource]

AI Cybersecurity: Insights for 2025

We surveyed 1,500+ cybersecurity professionals globally to explore their views, knowledge, and priorities on AI cybersecurity in 2025.