What is Vo1d APK malware?

Vo1d malware first appeared in the wild in September 2024 and has since evolved into one of the most widespread Android botnets ever observed. This large-scale Android malware primarily targets smart TVs and low-cost Android TV boxes. Initially, Vo1d was identified as a malicious backdoor capable of installing additional third-party software [1]. Its functionality soon expanded beyond the initial infection to include deploying further malicious payloads, running proxy services, and conducting ad fraud operations. By early 2025, it was estimated that Vo1d had infected 1.3 to 1.6 million devices worldwide [2].

From a technical perspective, Vo1d embeds components into system storage to enable itself to download and execute new modules at any time. External researchers further discovered that Vo1d uses Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) to create new command-and-control (C2) domains, ensuring that regardless of existing servers being taken down, the malware can quickly reconnect to new ones. Previous published analysis identified dozens of C2 domains and hundreds of DGA seeds, along with new downloader families. Over time, Vo1d has grown increasingly sophisticated with clear signs of stronger obfuscation and encryption methods designed to evade detection [2].

Darktrace’s coverage

Earlier this year, Darktrace observed a surge in Vo1d-related activity across customer environments, with the majority of affected customers based in South Africa. Devices that had been quietly operating as expected began exhibiting unusual network behavior, including excessive DNS lookups. Open-source intelligence (OSINT) has long highlighted South Africa as one of the countries most impacted by Vo1d infections [2].

What makes the recent activity particularly interesting is that the surge observed by Darktrace appears to be concentrated specifically in South African environments. This localized spike suggests that a significant number of devices may have been compromised, potentially due to vulnerable software, outdated firmware, or even preloaded malware. Regions with high prevalence of low-cost, often unpatched devices are especially susceptible, as these everyday consumer electronics can be quietly recruited into the botnet’s network. This specifically appears to be the case with South Africa, where public reporting has documented widespread use of low-cost boxes, such as non-Google-certified Android TV sticks, that frequently ship with outdated firmware [3].

The initial triage highlighted the core mechanism Vo1d uses to remain resilient: its use of DGA. A DGA deterministically creates a large list of pseudo-random domain names on a predictable schedule. This enables the malware to compute hundreds of candidate domains using the same algorithm, instead of using a hard-coded single C2 hostname that defenders could easily block or take down. To ensure reproducible from the infected device’s perspective, Vo1d utilizes DGA seeds. These seeds might be a static string, a numeric value, or a combination of underlying techniques that enable infected devices to generate the same list of candidate domains for a time window, provided the same DGA code, seed, and date are used.

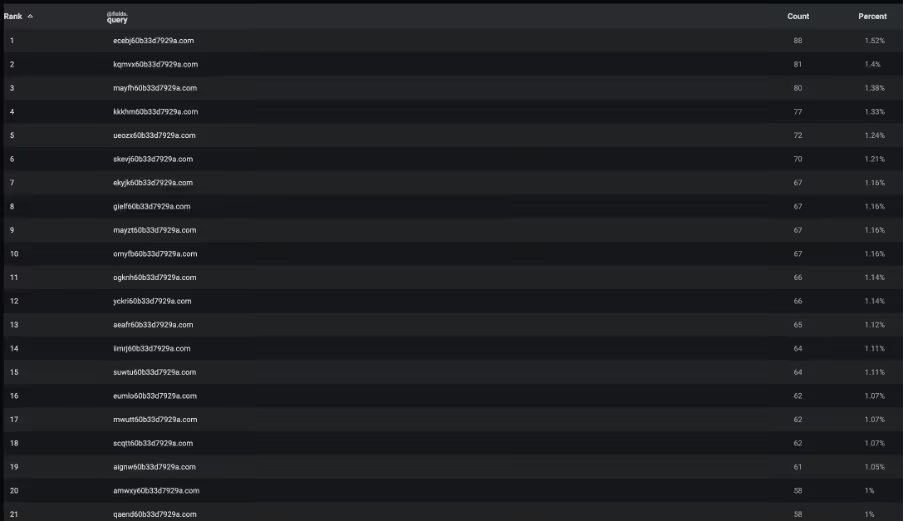

Interestingly, Vo1d’s DGA seeds do not appear to be entirely unpredictable, and the generated domains lack fully random-looking endings. As observed in Figure 1, there is a clear pattern in the names generated. In this case, researchers identified that while the first five characters would change to create the desired list of domain names, the trailing portion remained consistent as part of the seed: 60b33d7929a, which OSINT sources have linked to the Vo1d botnet. [2]. Darktrace’s Threat Research team also identified a potential second DGA seed, with devices in some cases also engaging in activity involving hostnames matching the regular expression /[a-z]{5}fc975904fc9\.(com|top|net). This second seed has not been reported by any OSINT vendors at the time of writing.

Another recurring characteristic observed across multiple cases was the choice of top-level domains (TLDs), which included .com, .net, and .top.

The activity was detected by multiple models in Darktrace / NETWORK™, which triggered on devices making an unusually large volume of DNS requests for domains uncommon across the network.

During the network investigation, Darktrace analysts traced Vo1d’s infrastructure and uncovered an interesting pattern related to responder ASNs. A significant number of connections pointed to AS16509 (AMAZON-02). By hosting redirectors or C2 nodes inside major cloud environments, Vo1d is able to gain access to highly available and geographically diverse infrastructure. When one node is taken down or reported, operators can quickly enable a new node under a different IP within the same ASN. Another feature of cloud infrastructure that hardens Vo1d’s resilience is the fact that many organizations allow outbound connections to cloud IP ranges by default, assuming they are legitimate. Despite this, Darktrace was able to identify the rarity of these endpoints, identifying the unusualness of the activity.

Analysts further observed that once a generated domain successfully resolved, infected devices consistently began establishing outbound connections to ephemeral port ranges like TCP ports 55520 and 55521. These destination ports are atypical for standard web or DNS traffic. Even though the choice of high-numbered ports appears random, it is likely far from not accidental. Commonly used ports such as port 80 (HTTP) or 443 (HTTPS) are often subject to more scrutiny and deeper inspection or content filtering, making them riskier for attackers. On the other hand, unregistered ports like 55520 and 55521 are less likely to be blocked, providing a more covert channel that blends with outbound TCP traffic. This tactic helps evade firewall rules that focus on common service ports. Regardless, Darktrace was able to identify external connections on uncommon ports to locations that the network does not normally visit.

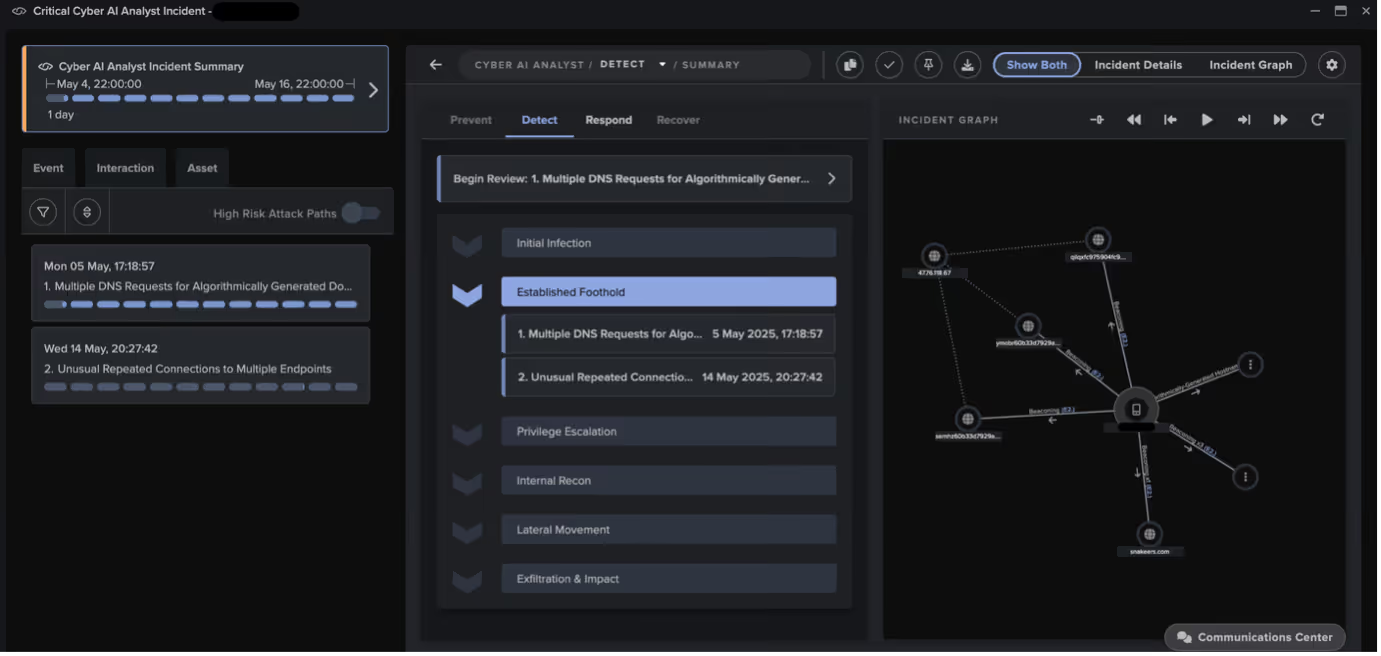

The continuation of the described activity was identified by Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst, which correlated individual events into a broader interconnected incident. It began with the multiple DNS requests for the algorithmically generated domains, followed by repeated connections to rare endpoints later confirmed as attacker-controlled infrastructure. Cyber AI Analyst’s investigation further enabled it to categorize the events as part of the “established foothold” phase of the attack.

Conclusion

The observations highlighted in this blog highlight the precision and scale of Vo1d’s operations, ranging from its DGA-generated domains to its covert use of high-numbered ports. The surge in affected South African environments illustrate how regions with many low-cost, often unpatched devices can become major hubs for botnet activity. This serves as a reminder that even everyday consumer electronics can play a role in cybercrime, emphasizing the need for vigilance and proactive security measures.

Credit to Christina Kreza (Cyber Analyst & Team Lead) and Eugene Chua (Principal Cyber Analyst & Team Lead)

Edited by Ryan Traill (Analyst Content Lead)

Appendices

Darktrace Model Detections

- Anomalous Connection / Devices Beaconing to New Rare IP

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Connections to New External TCP Port

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

- Compromise / DGA Beacon

- Compromise / Domain Fluxing

- Compromise / Fast Beaconing to DGA

- Unusual Activity / Unusual External Activity

List of Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

- 3.132.75[.]97 – IP address – Likely Vo1d C2 infrastructure

- g[.]sxim[.]me – Hostname – Likely Vo1d C2 infrastructure

- snakeers[.]com – Hostname – Likely Vo1d C2 infrastructure

Selected DGA IoCs

- semhz60b33d7929a[.]com – Hostname – Possible Vo1d C2 DGA endpoint

- ggqrb60b33d7929a[.]com – Hostname – Possible Vo1d C2 DGA endpoint

- eusji60b33d7929a[.]com – Hostname – Possible Vo1d C2 DGA endpoint

- uacfc60b33d7929a[.]com – Hostname – Possible Vo1d C2 DGA endpoint

- qilqxfc975904fc9[.]top – Hostname – Possible Vo1d C2 DGA endpoint

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

- T1071.004 – Command and Control – DNS

- T1568.002 – Command and Control – Domain Generation Algorithms

- T1568.001 – Command and Control – Fast Flux DNS

- T1571 – Command and Control – Non-Standard Port

[1] https://news.drweb.com/show/?lng=en&i=14900

[2] https://blog.xlab.qianxin.com/long-live-the-vo1d_botnet/

The content provided in this blog is published by Darktrace for general informational purposes only and reflects our understanding of cybersecurity topics, trends, incidents, and developments at the time of publication. While we strive to ensure accuracy and relevance, the information is provided “as is” without any representations or warranties, express or implied. Darktrace makes no guarantees regarding the completeness, accuracy, reliability, or timeliness of any information presented and expressly disclaims all warranties.

Nothing in this blog constitutes legal, technical, or professional advice, and readers should consult qualified professionals before acting on any information contained herein. Any references to third-party organizations, technologies, threat actors, or incidents are for informational purposes only and do not imply affiliation, endorsement, or recommendation.

Darktrace, its affiliates, employees, or agents shall not be held liable for any loss, damage, or harm arising from the use of or reliance on the information in this blog.

The cybersecurity landscape evolves rapidly, and blog content may become outdated or superseded. We reserve the right to update, modify, or remove any content.