Introduction

Malicious cyber actors are known to exploit vulnerabilities in Internet-facing systems and services to gain entry to organizations’ digital environments. Keeping track of the vulnerabilities which malicious actors are exploiting is seemingly futile, with malicious actors continually finding new avenues of exploitation.

In mid-April 2023, Darktrace, along with the wider security community, observed malicious cyber actors gaining entry to networks through exploitation of a critical vulnerability in the print management system, PaperCut. Darktrace observed two types of attack chain within its customer base, one involving the deployment of payloads to facilitate crypto-mining, and the other involving the deployment of a payload to facilitate Tor-based command-and-control (C2) communication.

Walking Through the Front Door

One of the most widely abused Initial Access methods attackers use to gain entry to an organization’s digital environment is the exploitation of vulnerabilities in Internet-facing systems and services [1]. The public disclosure of a critical vulnerability in a widely used, Internet-facing service, along with a proof of concept (POC) exploit for such vulnerability, provides malicious cyber actors with a key to the front door of countless organizations. Once malicious actors are in possession of such a key, security teams are in a race against time to patch all their vulnerable systems and services. But until organizations accomplish this, the doors are left open.

This year, the security community has seen malicious actors gaining entry to networks through the exploitation of vulnerabilities in a range of services. These services include familiar suspects, such as Microsoft Exchange and ManageEngine, along with less familiar suspects, such as PaperCut. PaperCut is a system for managing and tracking printing, copying, and scanning activity within organizations. In 2021, PaperCut was used in more than 50,000 sites across over 100 countries [2], making PaperCut a widely used print management system.

In January 2023, Trend Micro’s Zero Day Initiative (ZDI) notified PaperCut of a critical RCE vulnerability, namely CVE-2023–27350, in certain versions of PaperCut NG (PaperCut’s ‘print only’ variant) and PaperCut MF (PaperCut’s ‘extended feature’ variant) [3,4]. In March 2023, PaperCut released versions of PaperCut NG and PaperCut MF containing a fix for CVE-2023–27350 [4]. Despite this, security teams observed a surge in cases of malicious actors exploiting CVE-2023–27350 to compromise PaperCut servers in April 2023 [4-10]. This trend was mirrored in Darktrace’s customer base, where a surge in compromises of PaperCut servers was observed in April 2023.

Observed Attack Chains

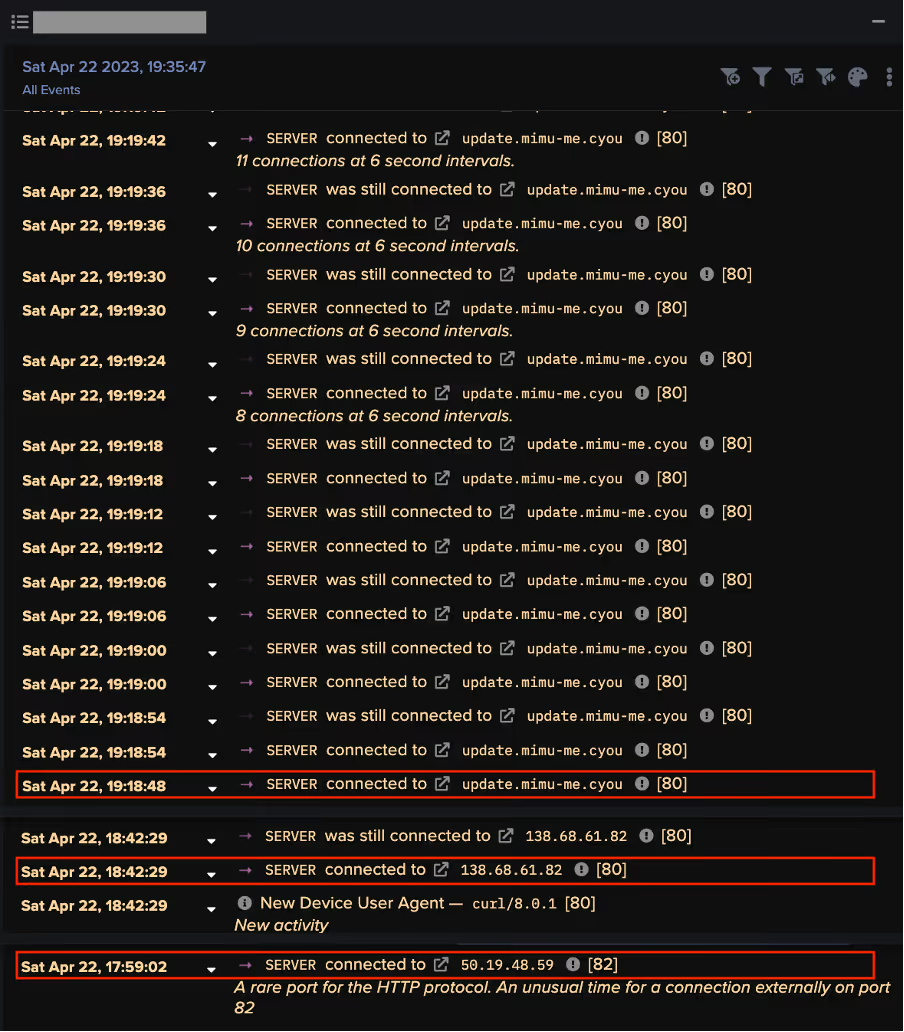

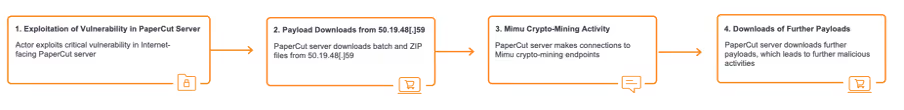

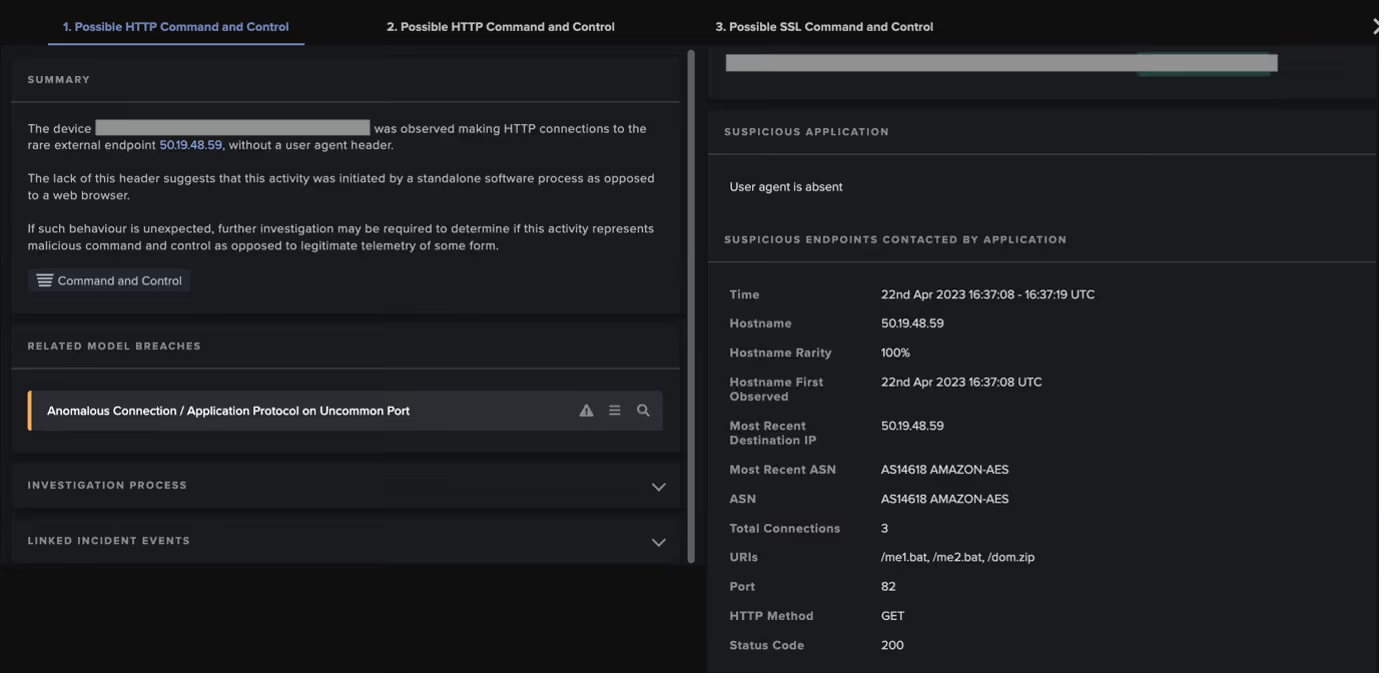

In mid-April 2023, Darktrace identified two related clusters of attack chains. The attack chains within the first of these clusters involved Internet-facing PaperCut servers downloading payloads with crypto-mining capabilities from the external location, 50.19.48[.]59. While the attack chains within the second of the clusters involved Internet-facing PaperCut servers downloading payloads with Tor-based C2 capabilities from 192.184.35[.]216. The attack chains within the first cluster, which were observed on April 22, 2023, will be referred to as ‘50.19.48[.]59 chains’ and the attack chains in the second cluster, observed on April 24, 2023, will be called ‘192.184.35[.]216 chains’.

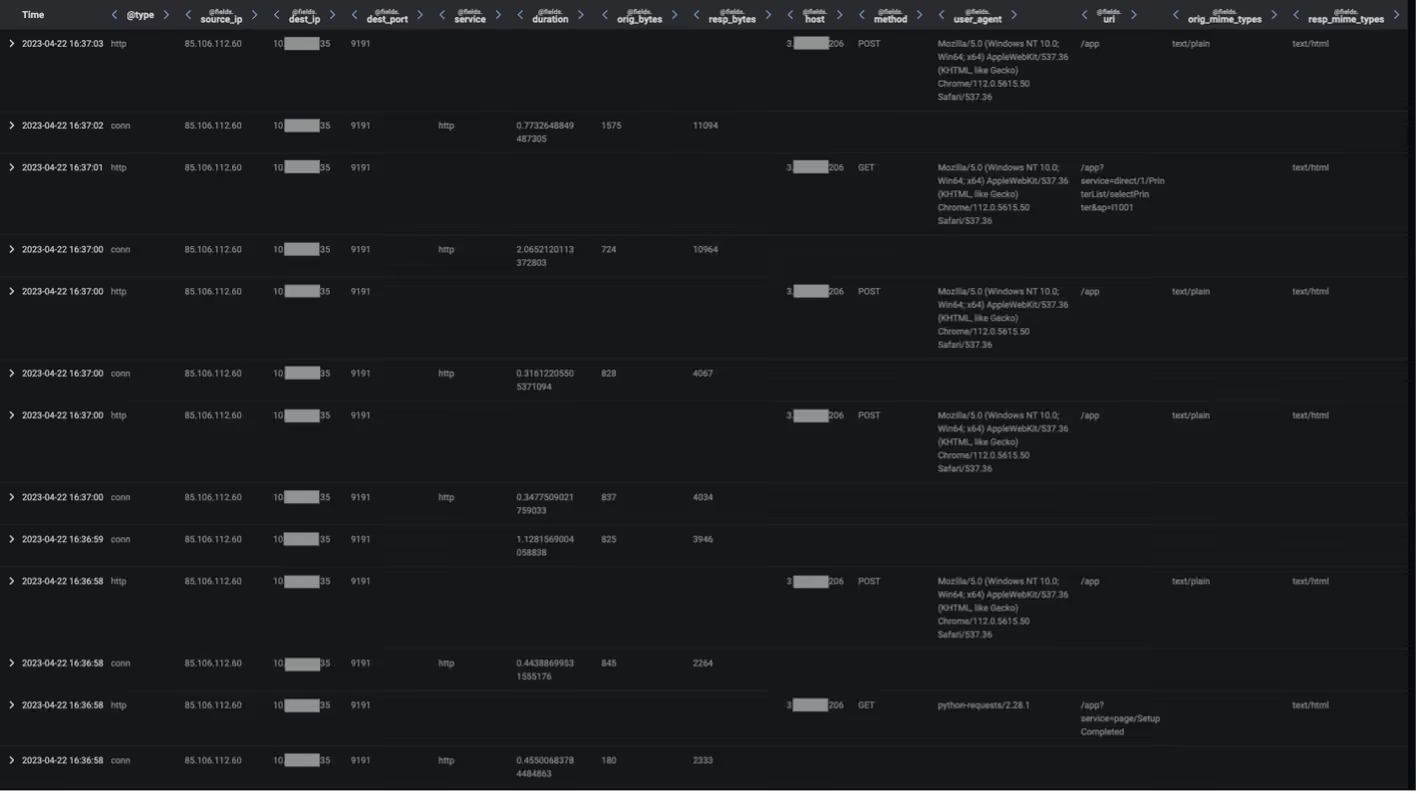

Both attack chains started with highly unusual external endpoints contacting the '/SetupCompleted' endpoint of an Internet-facing PaperCut server. These requests to the ‘/SetupCompleted’ endpoint likely represented attempts to exploit CVE-2023–27350 [10]. 50.19.48[.]59 chains started with exploit connections from the external endpoint, 85.106.112[.]60, whereas 192.184.35[.]216 chains started with exploit connections from Tor nodes, such as 185.34.33[.]2.

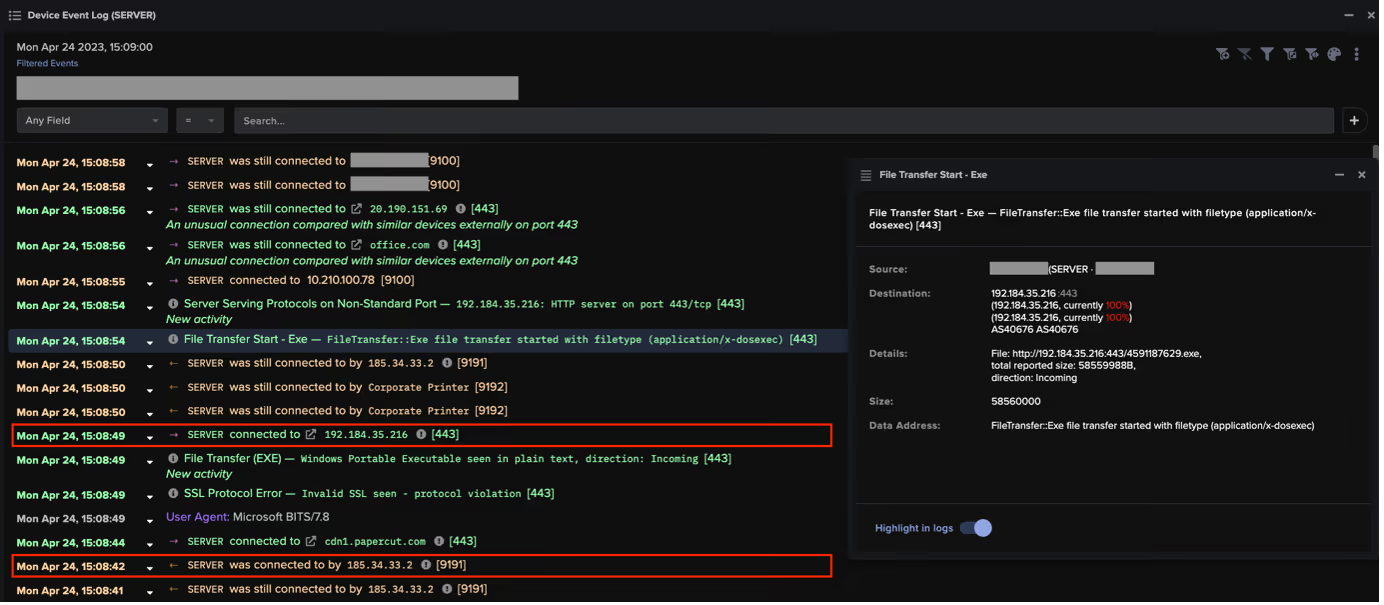

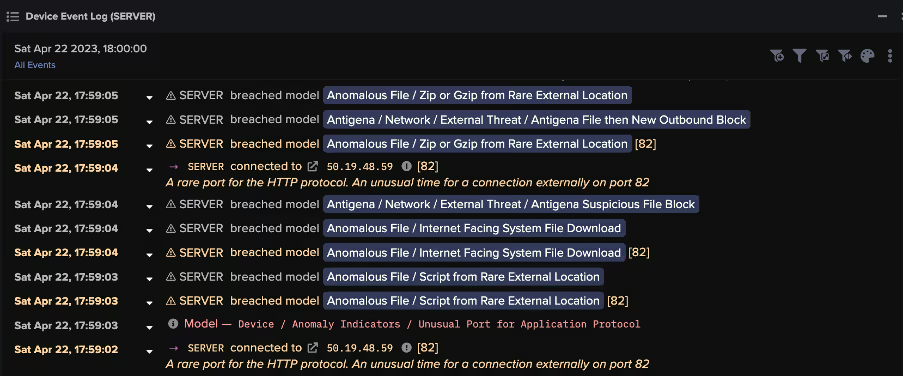

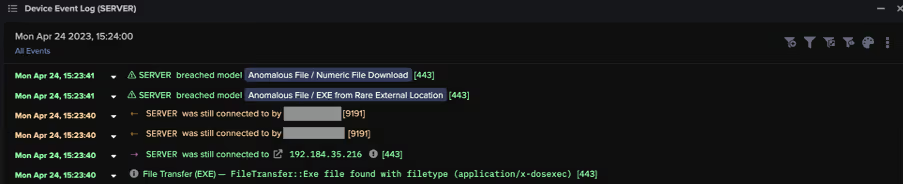

After the exploitation step, the two attack chains took different paths. In the 50.19.48[.]59 chains, the exploitation step was followed by the affected PaperCut server making HTTP GET requests over port 82 to the rare external endpoint, 50.19.48[.]59. In the 192.184.35[.]216 chains, the exploitation step was followed by the affected PaperCut server making an HTTP GET request over port 443 to 192.184.35[.]216.

The HTTP GET requests to 50.19.48[.]59 had Target URIs such as ‘/me1.bat’, ‘/me2.bat’, ‘/dom.zip’, ‘/mazar.bat’, and ‘/mazar.zip’, whilst the HTTP GET requests to 192.184.35[.]216 had the Target URI ‘/4591187629.exe’. The User-Agent header of the GET requests to 192.184.35[.]216 indicated that that the malicious file transfers were initiated through Microsoft’s pre-installed Background Intelligent Transfer Service (BITS).

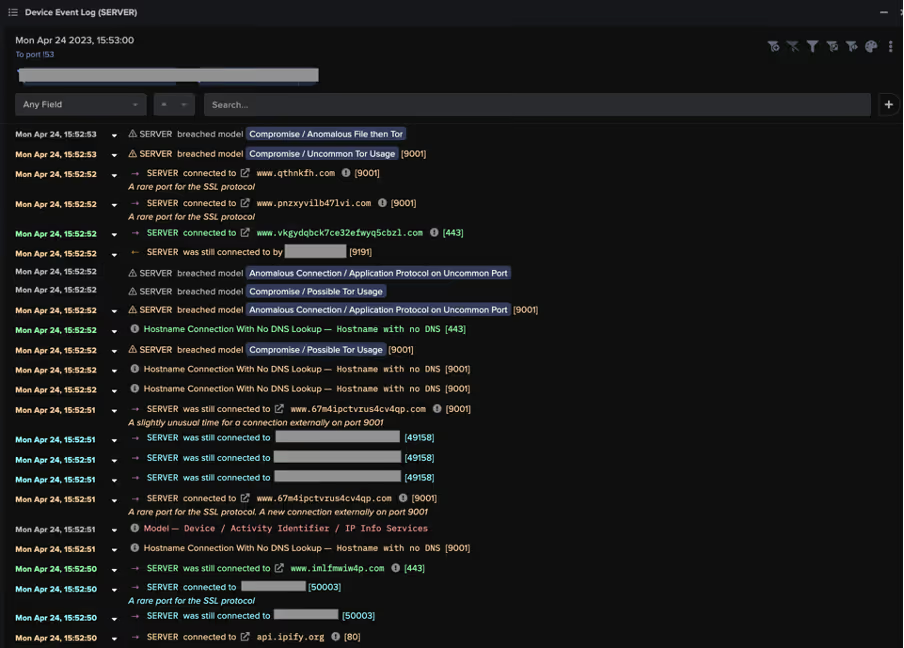

Downloads from 50.19.48[.]59 were followed by cURL GET requests to 138.68.61[.]82 and then connections to external endpoints associated with the cryptocurrency miner, Mimu (as seen in Fig 4). Downloads from 192.184.35[.]216 were followed by Python-urllib GET requests to api.ipify[.]org and long connections to Tor nodes (as seen in Fig 5).

These facts suggest that the actor behind the 50.19.48[.]59 chains were seeking to drop cryptocurrency miners on PaperCut servers, with the intention of abusing the customer’s network to carry out resource intensive and costly cryptocurrency mining activity. Meanwhile, the actors behind the 192.184.35[.]216 chains were likely attempting to establish a Tor-based C2 channel with PaperCut servers to allow actors to further communicate with compromised devices.

The activities ensuing from both attack chains were varied, making it difficult to ascertain whether the activities were steps of separate attack chains, or steps of the existing 50.19.48[.]59 and 192.184.35[.]216 chains. A wide variety of activities ensued from observed 50.19.48[.]59 and 192.184.35[.]216 chains, including the abuse of pre-installed tools, such as cURL, CertUtil, and PowerShell to transfer further payloads to PaperCut servers, Cobalt Strike C2 communication, Ngrok usage, Mimikatz usage, AnyDesk usage, and in one case, detonation of the LockBit ransomware strain.

As the PaperCut servers that were targeted by malicious actors are Internet-facing, they regularly receive connections from unusual external endpoints. The exploit connections in the 50.19.48[.]59 and 192.184.35[.]216 chains, which originated from unusual external endpoints, were therefore not detected by Darktrace DETECT™, which relies on anomaly-based methods to detect network-based steps of an intrusion.

On the other hand, the post-exploitation steps of the 50.19.48[.]59 and 192.184.35[.]216 chains yielded ample anomaly-based detections, given that they consisted of PaperCut servers displaying highly unusual behaviors. As such Darktrace DETECT was able to successfully identify multiple chains of suspicious activity, including unusual file downloads from external endpoints and beaconing activity to rare external locations.

The file downloads from 50.19.48[.]59 observed in the 50.19.48[.]59 chains caused the following Darktrace DETECT models to breach:

- Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port

- Anomalous File / Internet Facing System File Download

- Anomalous File / Script from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Zip or Gzip from Rare External Location

- Device / Internet Facing Device with High Priority Alert

The file downloads from 192.184.35[.]216 observed in the 192.184.35[.]216 chains caused the following Darktrace DETECT models to breach:

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Numeric File Download

- Device / Internet Facing Device with High Priority Alert

Subsequent C2, beaconing, and crypto-mining connections in the 50.19.48[.]59 chains caused the following Darktrace DETECT models to breach:

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Server Activity / New User Agent from Internet Facing System

- Anomalous Server Activity / Rare External from Server

- Compromise / Crypto Currency Mining Activity

- Compromise / High Priority Crypto Currency Mining

- Compromise / High Volume of Connections with Beacon Score

- Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Failed Connections

- Compromise / SSL Beaconing to Rare Destination

- Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

- Device / Large Number of Model Breaches

Subsequent C2, beaconing, and Tor connections in the 192.184.35[.]216 chains caused the following Darktrace DETECT models to breach:

- Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port

- Compromise / Anomalous File then Tor

- Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Compromise / Possible Tor Usage

- Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Compromise / Uncommon Tor Usage

- Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

Darktrace RESPOND

Darktrace RESPOND™ was not active in any of the networks affected by 192.184.35[.]216 activity, however, RESPOND was active in some of the networks affected by 50.19.48[.]59 activity. In those environments where RESPOND was enabled in autonomous mode, observed malicious activities resulted in intervention from RESPOND, including autonomous actions like blocking connections to specific external endpoints, blocking all outgoing traffic, and restricting affected devices to a pre-established pattern of behavior.

Darktrace Cyber AI Analyst

Cyber AI Analyst autonomously investigated model breaches caused by events within these 50.19.48[.]59 and 192.184.35[.]216 chains. Cyber AI Analyst created user-friendly and detailed descriptions of these events, and then linked together these descriptions into threads representing the attack chains. Darktrace DETECT thus uncovered the individual steps of the attack chains, while Cyber AI Analyst was able to piece together the individual steps and uncover the attack chains themselves.

Conclusion

The existence of critical vulnerabilities in third-party software leaves organizations at constant risk of malicious actors breaching the perimeters of their networks. This risk can be mitigated through attack surface management and regular patching. However, this does not eliminate cyber risk entirely, meaning that organizations must be prepared for the eventuality of malicious actors getting inside their digital estate.

In April 2023, Darktrace observed malicious actors breaching the perimeters of several customer networks through exploitation of a critical vulnerability in PaperCut. Darktrace DETECT observed actors exploiting PaperCut servers to conduct a wide variety of post-exploitation activities, including downloading malicious payloads associated with cryptocurrency mining or payloads with Tor-based C2 capabilities. Darktrace DETECT created numerous model breaches based on this activity which alerted then customer’s security teams early in their development, providing them with ample time to take mitigative steps.

The successful detection of this payload delivery activity, along with the crypto-mining, beaconing, and Tor C2 activities which followed, elicited Darktrace RESPOND to take autonomous inhibitive action against the ongoing activity in those environments where it was operating in autonomous response mode.

If left to unfold, these intrusions developed in a variety of ways, in some cases leading to Cobalt Strike and ransomware activity. The detection of these intrusions in their early stages thus played a vital role in preventing malicious cyber actors from causing significant disruption.

Credit to: Sam Lister, Senior SOC Analyst, Zoe Tilsiter, Senior Cyber Analyst.

Appendices

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Initial Access techniques:

- Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190)

Execution techniques:

- Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell (T1059.001)

Discovery techniques:

- System Network Configuration Discovery (T1016)

Command and Control techniques

- Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols (T1071.001)

- Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography (T1573.002)

- Ingress Tool Transfer (T1105)

- Non-Standard Port (T1571)

- Protocol Tunneling (T1572)

- Proxy: Multi-hop Proxy (T1090.003)

- Remote Access Software (T1219)

Defense Evasion techniques:

- BITS Jobs (T1197)

Impact techniques:

- Data Encrypted for Impact (T1486)

List of Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

IoCs from 50.19.48[.]59 attack chains:

- 85.106.112[.]60

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/me1.bat

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/me2.bat

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/dom.zip

- 138.68.61[.]82

- update.mimu-me[.]cyou • 102.130.112[.]157

- 34.195.77[.]216

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/mazar.bat

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/mazar.zip

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/prx.bat

- http://50.19.48[.]59:82/lol.exe

- http://77.91.85[.]117/122.exe

- windows.n1tro[.]cyou • 176.28.51[.]151

- 77.91.85[.]117

- 91.149.237[.]76

- kernel-mlclosoft[.]site • 104.21.29[.]206

- tunnel.us.ngrok[.]com • 3.134.73[.]173

- 212.113.116[.]105

- c34a54599a1fbaf1786aa6d633545a60 (JA3 client fingerprint of crypto-mining client)

IoCs from 192.184.35[.]216 attack chains:

- 185.56.83[.]83

- 185.34.33[.]2

- http://192.184.35[.]216:443/4591187629.exe

- api.ipify[.]org • 104.237.62[.]211

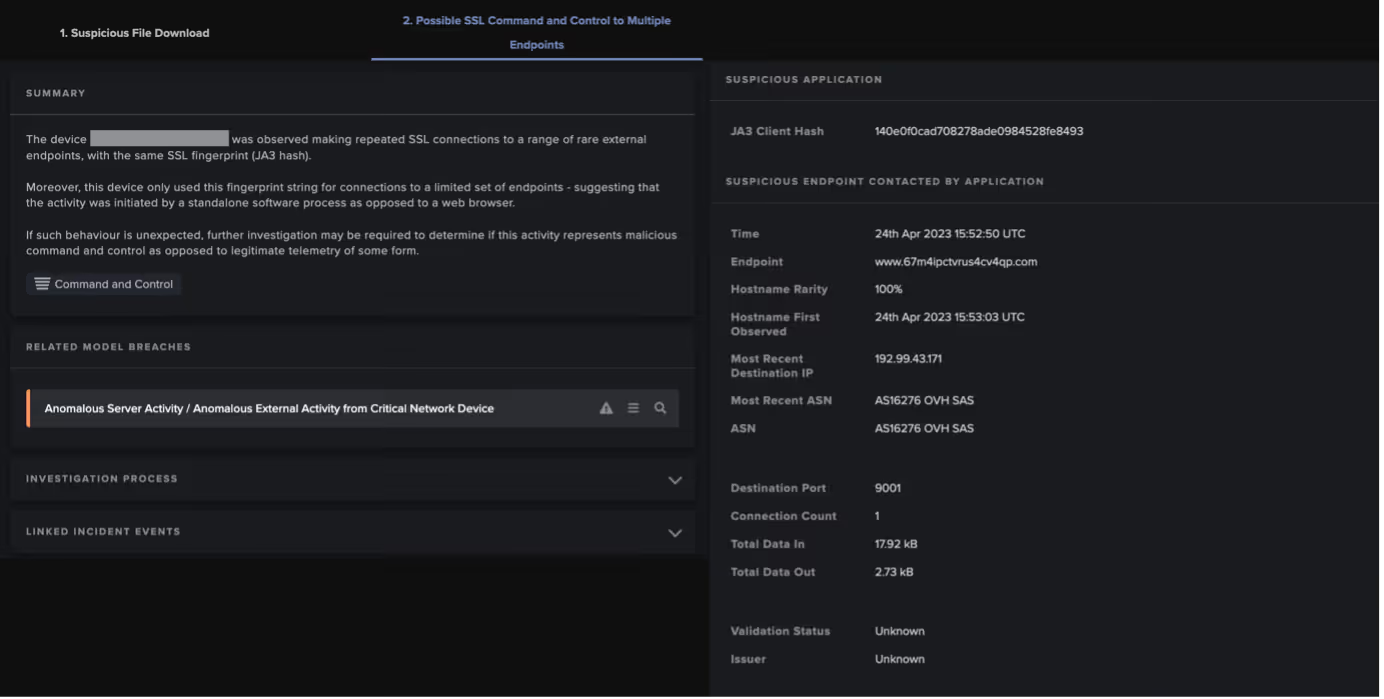

- www.67m4ipctvrus4cv4qp[.]com • 192.99.43[.]171

- www.ynbznxjq2sckwq3i[.]com • 51.89.106[.]29

- www.kuo2izmlm2silhc[.]com • 51.89.106[.]29

- 148.251.136[.]16

- 51.158.231[.]208

- 51.75.153[.]22

- 82.66.61[.]19

- backmainstream-ltd[.]com • 77.91.72[.]149

- 159.65.42[.]223

- 185.254.37[.]236

- http://137.184.56[.]77:443/for.ps1

- http://137.184.56[.]77:443/c.bat

- 45.88.66[.]59

- http://5.8.18[.]237/download/Load64.exe

- http://5.8.18[.]237/download/sdb64.dll

- 140e0f0cad708278ade0984528fe8493 (JA3 client fingerprint of Tor-based client)

References

[1] https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa22-137a

[2] https://www.papercut.com/kb/Main/PaperCutMFSolutionBrief/

[3] https://www.zerodayinitiative.com/advisories/ZDI-23-233/

[4] https://www.papercut.com/kb/Main/PO-1216-and-PO-1219

[6] https://www.huntress.com/blog/critical-vulnerabilities-in-papercut-print-management-software

[8] https://twitter.com/MsftSecIntel/status/1651346653901725696

[9] https://twitter.com/MsftSecIntel/status/1654610012457648129

[10] https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-131a

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)