As the USA prepared for a holiday weekend ahead of the Fourth of July, the ransomware group REvil were leveraging a vulnerability in Kaseya software to attack Managed Service Providers (MSPs) and their downstream customers. At least 1,500 companies appear to have been affected, even ones with no direct relationship to Kaseya.

At the time of writing, it appears that a zero-day vulnerability was used to gain access to the Kaseya VSA servers, before deploying ransomware on the endpoints managed by those VSA servers. This modus operandi vastly differs from previous ransomware campaigns which have traditionally been human-operated, direct intrusions.

The analysis below offers Darktrace’s insights into the campaign by looking at a real-life example. It highlights how Self-Learning AI detected the ransomware attack, and how Antigena protected customer data on the network from being encrypted.

Dissecting REvil ransomware from the network perspective

Antigena detected the first signs of ransomware on the network as soon as encryption had begun. The graphic below illustrates the start of the ransomware encryption over SMB shares. When the graphic was taken, the attack was happening live and had never been seen before. As it was a novel threat, Darktrace stopped the network encryption without any static signatures or rules.

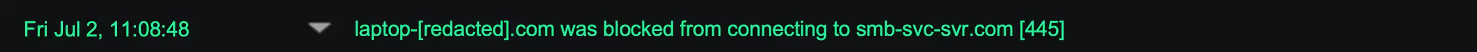

The ransomware began to take action at 11:08:32, shown by the ‘SMB Delete Success’ from the infected laptop to an SMB server. While the laptop sometimes reads files on that SMB server, it never deletes these types of files on this particular file share, so Darktrace detected this activity as new and unusual.

Simultaneously, the infected laptop created the ransom note ‘943860t-readme.txt’. Again, the ‘SMB Write Success’ to the SMB server was new activity – and crucially, Darktrace did not look for a static string or a known ransom note. Instead – by previously learning the ‘normal’ behavior of every entity, peer group, and the overall enterprise – it identified that the activity was unusual and new for this organization and device.

By detecting and correlating these subtle anomalies, Darktrace identified this as the earliest stages of ransomware encryption on the network and Antigena took immediate action.

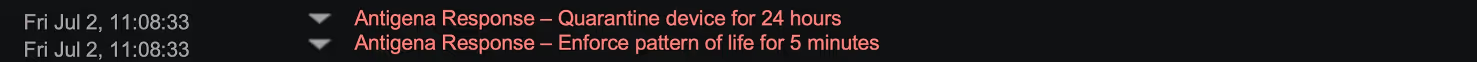

Antigena took two precise steps:

- Enforce ‘pattern of life’ for five minutes: This prevented the infected laptop from making any connections that were new or unusual. In this case, it prevented any further new SMB encryption activity.

- Quarantine device for 24 hours: Usually, Antigena would not take such drastic action, but it was clear that this activity closely resembled ransomware behavior, so Antigena decided to quarantine the device on the network completely to prevent it from doing any further damage.

For several minutes, the infected laptop kept trying to connect to other internal devices via SMB to continue the encryption activity. It was blocked by Antigena at every stage, limiting the spread of the attack and mitigating any damage posed via the network encryption.

On a technical level, Antigena delivered the blocking mechanisms via integrations with native security controls such as existing firewalls, or by taking action itself to disrupt the connections.

The below graphic shows the ‘pattern of life’ for all network connections for the infected laptop. The three red dots represent Darktrace’s detections and pinpoint the exact moment in time when REvil ransomware was installed on the laptop. The graphic also shows an abrupt stop to all network communication as Antigena quarantined the device.

Attacks will always get in

During the incident, part of the encryption happened locally on the endpoint device, which Darktrace had no visibility over. Furthermore, the Internet-facing Kaseya VSA server that was initially compromised was not visible to Darktrace in this case.

Nevertheless, Self-Learning AI detected the infection as soon as it reached the network. This shows the importance of being able to defend against active ransomware within the enterprise. Organizations cannot rely solely on a single layer of defense to keep threats out. An attacker will always – eventually – breach your environment. Defense therefore needs to change its approach towards detecting and mitigating damage once an adversary is inside.

Many cyber-attacks succeed in bypassing endpoint controls and begin to spread aggressively in corporate environments. Autonomous Response can provide resilience in such cases, even for novel campaigns and new strains of malware.

Thanks to Self-Learning AI, ransomware from the REvil attack could not perform any encryption over the network, and files available on that network were saved. This included the organization’s critical file servers which did not have Kaseya installed and thus did not receive the initial payload via the malicious update directly. By interrupting the attack as it happened, Antigena prevented thousands of files on network shares from being encrypted.

Further observations

Data exfiltration

In contrast to other REvil intrusions Darktrace has caught in the past, no data exfiltration has been observed. This is interesting as it differs from the general trend this last year where cyber-criminal groups generally focus more on the exfiltration of data to hold their victims to ransom, in response to companies becoming better with backups.

Bitcoin

REvil has demanded a total payment of $70 million in Bitcoin. For a group that tries to maximize their profits, this seems odd for two reasons:

- How do they expect a single entity to collect $70 million from potentially thousands of affected organizations? They must be aware of the massive logistical challenges behind this, even if they do expect Kaseya to act as a focal point for collecting the money.

- Since DarkSide lost access to most of the Colonial Pipeline ransom, ransomware groups have shifted to demanding payments in Monero rather than Bitcoin. Monero appears to be more difficult to track for law enforcement agencies. The fact REvil are using Bitcoin, a more traceable cryptocurrency, appears counter-productive to their usual goal of maximizing profits.

Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS)

Darktrace also noticed that other, more traditional ‘big game hunting’ REvil ransomware operations took place over the same weekend. This is not surprising as REvil is running a RaaS model, so it is likely some affiliate groups continued their regular big game hunting attacks while the Kaseya supply chain attack was underway.

Unpredictable is not undefendable

The weekend of the Fourth of July experienced major supply chain attacks against Kaseya and separately, against California-based distributor Synnex. Threats are coming from every direction – leveraging zero-days, social engineering tactics, and other advanced tools.

The case study above demonstrates how self-learning technology detects such attacks and minimizes the damage. It functions as a crucial part of defense-in-depth when other layers – such as endpoint protection, threat intelligence or known signatures and rules – fail to detect unknown threats.

The attack happened in milliseconds, faster than any human security team could react. Autonomous Response has proven invaluable in outpacing this new generation of machine-speed threats. It keeps thousands of organizations safe around the world, around the clock, stopping an attack every second.

Darktrace model detections

- Compromise / Ransomware / Suspicious SMB Activity

- Compromise / Ransomware / Suspicious SMB File Extension

- Compromise / Ransomware / Ransom or Offensive Words Written to SMB

- Compromise / Ransomware / Ransom or Offensive Words Read from SMB

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)