Introduction

Last year provided further evidence that the cyber threat landscape remains both complex and challenging to predict. Between uncertain attribution, novel exploits and rapid malware developments, it is becoming harder to know where to focus security efforts. One of the largest surprises of 2021 was the re-emergence of the infamous Emotet botnet. This is an example of a campaign that ignored industry verticals or regions and seemingly targeted companies indiscriminately. Only 10 months after the Emotet takedown by law enforcement agencies in January, new Emotet activities in November were discovered by security researchers. These continued into the first quarter of 2022, a period which this blog will explore through findings from the Darktrace Threat Intel Unit.

Dating back to 2019, Emotet was known to deliver Trickbot payloads which ultimately deployed Ryuk ransomware strains on compromised devices. This interconnectivity highlighted the hydra-like nature of threat groups wherein eliminating one (even with full-scale law enforcement intervention) would not rule them out as a threat nor indicate that the threat landscape would be any more secure.

When Emotet resurged, as expected, one of the initial infection vectors involved leveraging existing Trickbot infrastructure. However, unlike the original attacks, it featured a brand new phishing campaign.

Although similar to the original Emotet infections, the new wave of infections has been classified into two categories: Epochs 4 and 5. These had several key differences compared to Epochs 1 to 3. Within Darktrace’s global deployments, Emotet compromises associated to Epoch 4 appeared to be the most prevalent. Affected customer environments were seen within a large range of countries (Figure 1) and industry verticals such as manufacturing and supply chain, hospitality and travel, public administration, technology and telecoms and healthcare. Company demographics and size did not appear to be a targeting factor as affected customers had varying employee counts ranging from less than 250, to over 5000.

Key differences between Epochs 1-3 vs 4-5

Based on wider security research into the innerworkings of the Emotet exploits, several key differences were identified between Epochs 4/5 and its predecessors. The newer epochs used:

· A different Microsoft document format (OLE vs XML-based).

· A different encryption algorithm for communication. The new epochs used Elliptic Curve Cryptograph (ECC) [1] with public encryption keys contained in the C2 configuration file [2]. This was different from the previous Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) key encryption method.

· Control Flow Flattening was used as an obfuscation technique to make detection and reverse engineering more difficult. This is done by hiding a program’s control flow [3].

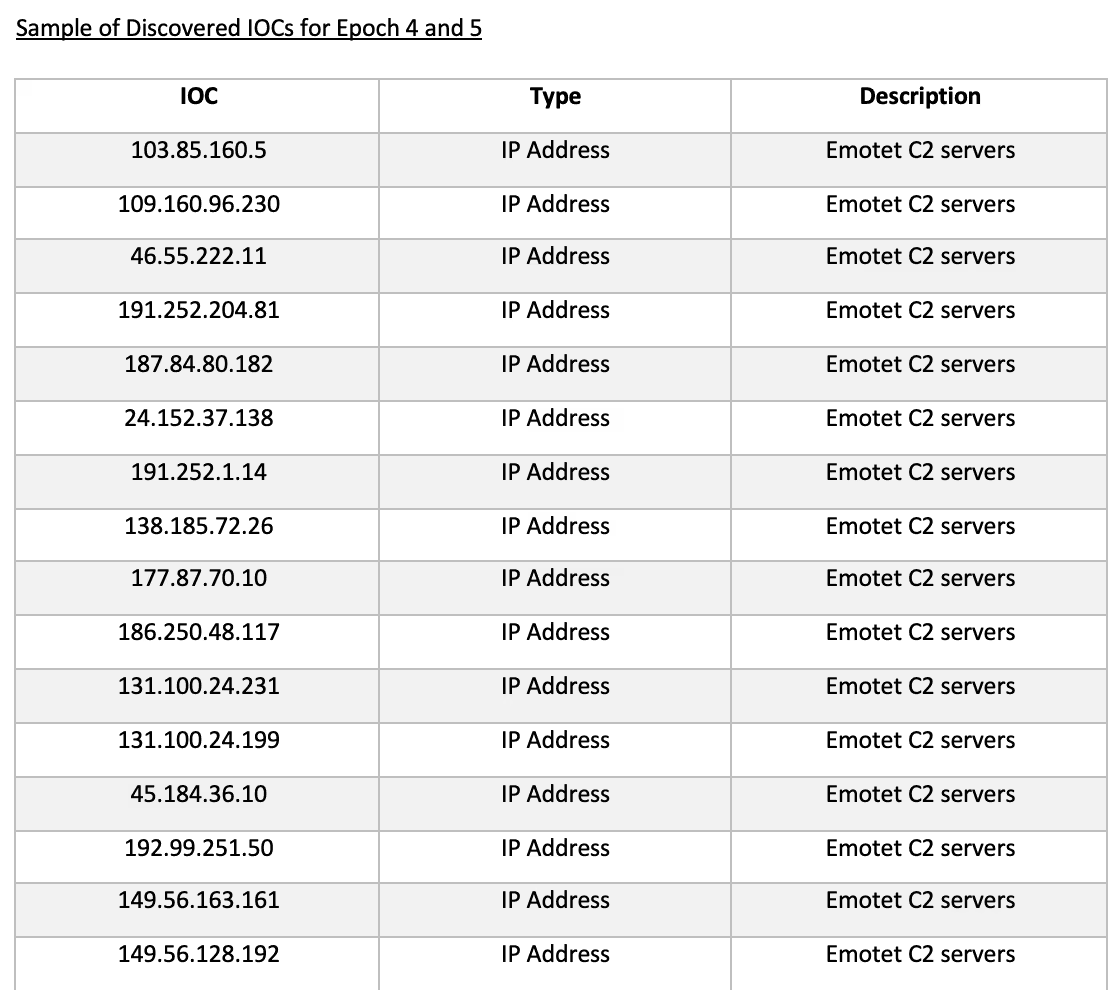

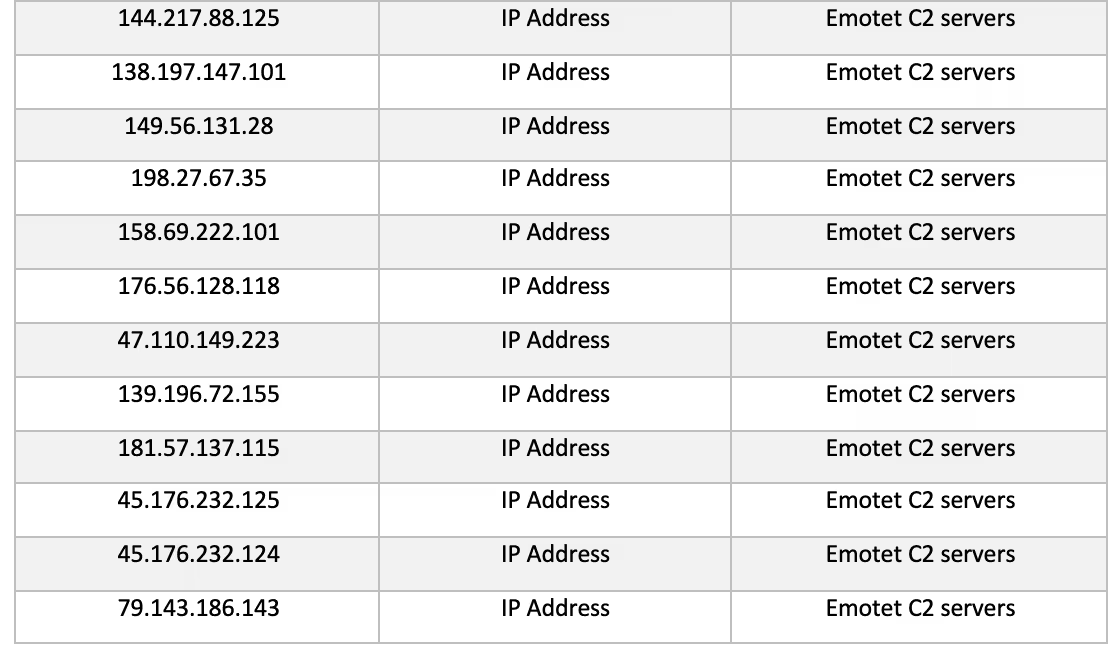

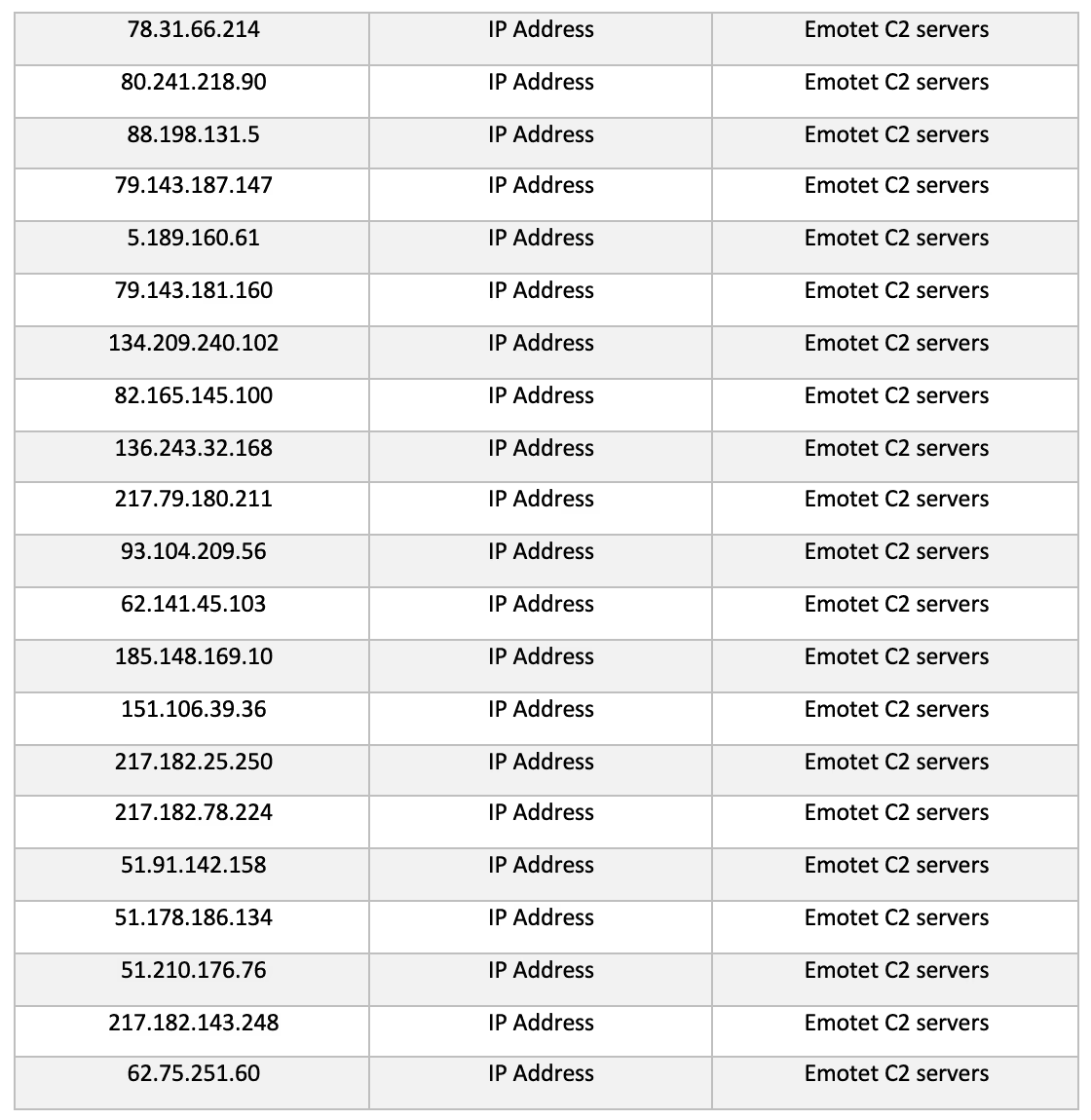

· New C2 infrastructure was observed as C2 communications were directed to over 230 unique IPs all associated to the new Epochs 4 and 5.

In addition to the new Epoch 4 and 5 features, Darktrace detected unsurprising similarities in those deployments affected by the renewed campaign. This included self-signed SSL connections to Emotet’s new infrastructure as well as malware spam activities to multiple rare external endpoints. Preceding these outbound communications, devices across multiple deployments were detected downloading Emotet-associated payloads (algorithmically generated DLL files).

Emotet Resurgence Campaign

1. Initial Compromise

The initial point of entry for the resurgence activity was almost certainly via Trickbot infrastructure or a successful phishing attack (Figure 2). Following the initial intrusion, the malware strain begins to download payloads via macro-ladened files which are used to spawn PowerShell for subsequent malware downloads.

Following the downloads, malicious communication with Emotet’s C2 infrastructure was observed alongside activities from the spam module. Within Darktrace, key techniques were observed and documented below.

2. Establish Foothold: Binary Dynamic-link library (.dll) with algorithmically generated filenames

Emotet payloads are polymorphic and contain algorithmically generated filenames . Within deployments, HTTP GET requests involving a suspicious hostname, www[.]arkpp[.]com, and Emotet related samples such as those seen below were observed:

· hpixQfCoJb0fS1.dll (SHA256 hash: 859a41b911688b00e104e9c474fc7aaf7b1f2d6e885e8d7fbf11347bc2e21eaa)

· M0uZ6kd8hnzVUt2BNbRzRFjRoz08WFYfPj2.dll (SHA256 hash: 9fbd590cf65cbfb2b842d46d82e886e3acb5bfecfdb82afc22a5f95bda7dd804)

· TpipJHHy7P.dll (SHA256 hash: 40060259d583b8cf83336bc50cc7a7d9e0a4de22b9a04e62ddc6ca5dedd6754b)

These DLL files likely represent the distribution of Emotet loaders which depends on windows processes such as rundll32[.]exe and regsvr32[.]exe to execute.

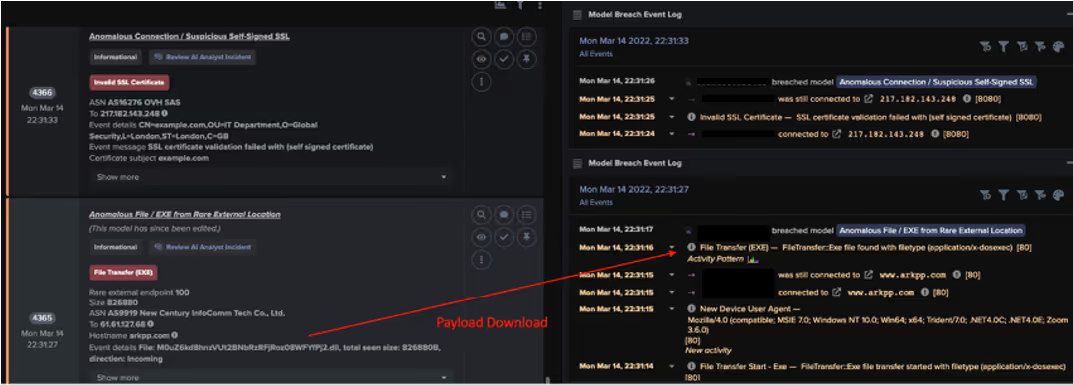

3. Establish Foothold: Outbound SSL connections to Emotet C2 servers

A clear network indicator of compromise for Emotet’s C2 communication involved self-signed SSL using certificate issuers and subjects which matched ‘CN=example[.]com,OU=IT Department,O=Global Security,L=London,ST=London,C=GB’ , and a common JA3 client fingerprint (72a589da586844d7f0818ce684948eea). The primary C2 communications were seen involving infrastructures classified as Epoch 4 rather than 5. Despite encryption in the communication content, network contextual connection details were sufficient for the detection of the C2 activities (Figure 3).

Outbound SSL and SMTP connections on TCP ports 25, 465, 587

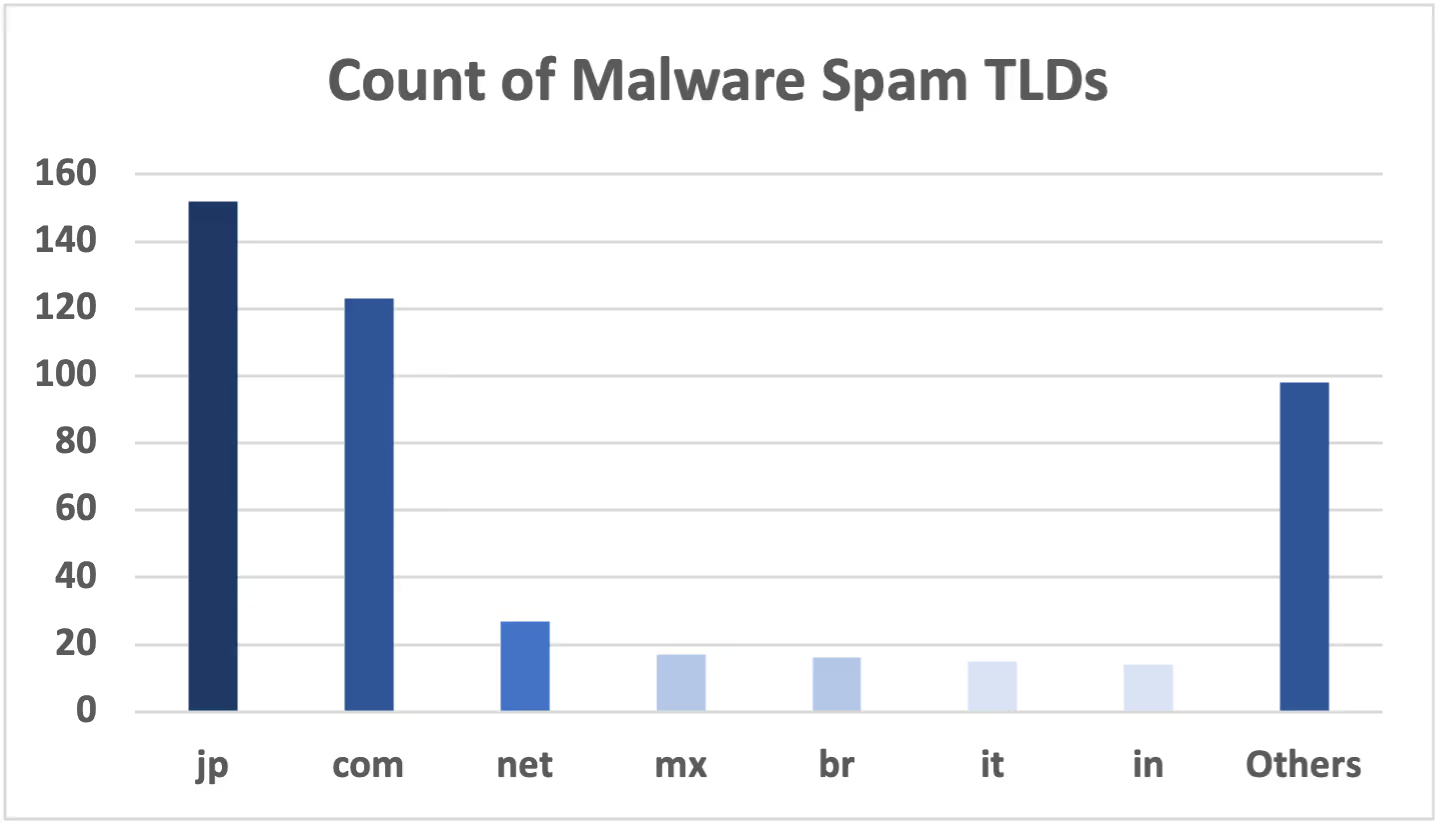

An anomalous user agent such as, ‘Microsoft Outlook 15.0’, was observed being used for SMTP connections with some subject lines of the outbound emails containing Base64-encoded strings. In addition, this JA3 client fingerprint (37cdab6ff1bd1c195bacb776c5213bf2) was commonly seen from the SSL connections. Based on the set of malware spam hostnames observed across at least 10 deployments, the majority of the TLDs were .jp, .com, .net, .mx, with the Japanese TLD being the most common (Figure 4).

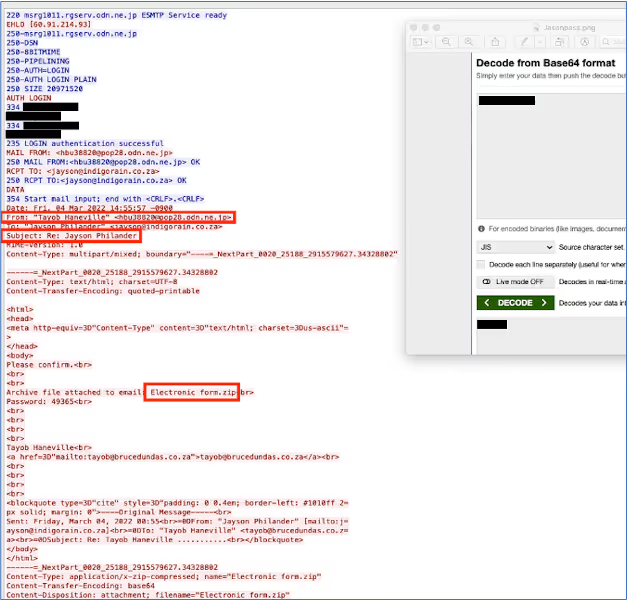

Plaintext spam content generated from the spam module were seen in PCAPs (Figure 5). Examples of clear phishing or spam indicators included 1) mismatched personal header and email headers, 2) unusual reply chain and recipient references in the subject line, and 3) suspicious compressed file attachments, e.g. Electronic form[.]zip.

4. Accomplish Mission

The Emotet resurgence also showed through secondary compromises involving anomalous SMB drive writes related to CobaltStrike. This consistently included the following JA3 hash (72a589da586844d7f0818ce684948eea) seen in SSL activities as well as SMB writes involving the svchost.exe file.

Darktrace Detection

The key DETECT models used to identify Emotet Resurgence activities were focused on determining possible C2. These included:

· Suspicious SSL Activity

· Suspicious Self-Signed SSL

· Rare External SSL Self-Signed

· Possible Outbound Spam

File-focused models were also beneficial and included:

· Zip or Gzip from Rare External Location

· EXE from Rare External Location

Darktrace’s detection capabilities can also be shown through a sample of case studies identified during the Threat Research team’s investigations.

Case Studies

Darktrace’s detection of Emotet activities was not limited by industry verticals or company sizing. Although there were many similar features seen across the new epoch, each incident displayed varying techniques from the campaign. This is shown in two client environments below:

When investigating a large customer environment within the public administration sector, 16 different devices were detected making 52,536 SSL connections with the example[.]com issuer. Devices associated with this issuer were mainly seen breaching the same Self-Signed and Spam DETECT models. Although anomalous incoming octet-streams were observed prior to this SSL, there was no clear relation between the downloads and the Emotet C2 connections. Despite the total affected devices occupying only a small portion of the total network, Darktrace analysts were able to filter against the much larger network ‘noise’ and locate detailed evidence of compromise to notify the customer.

Darktrace also identified new Emotet activities in much smaller customer environments. Looking at a company in the healthcare and pharmaceutical sector, from mid-March 2022 a single internal device was detected making an HTTP GET request to the host arkpp[.]com involving the algorithmically-generated DLL, TpipJHHy7P.dll with the SHA256 hash: 40060259d583b8cf83336bc50cc7a7d9e0a4de22b9a04e62ddc6ca5dedd6754b (Figure 6).

After the sample was downloaded, the device contacted a large number of endpoints that had never been contacted by devices on the network. The endpoints were contacted over ports 443, 8080, and 7080 involving Emotet related IOCs and the same SSL certificate mentioned previously. Malware spam activities were also observed during a similar timeframe.

The Emotet case studies above demonstrate how autonomous detection of an anomalous sequence of activities - without depending on conventional rules and signatures - can reveal significant threat activities. Though possible staged payloads were only seen in a proportion of the affected environments, the following outbound C2 and malware spam activities involving many endpoints and ports were sufficient for the detection of Emotet.

If present, in both instances Darktrace’s Autonomous Response technology, RESPOND, would recommend or implement surgical actions to precisely target activities associated with the staged payload downloads, outgoing C2 communications, and malware spam activities. Additionally, restriction to the devices’ normal pattern of life will prevent simultaneously occurring malicious activities while enabling the continuity of normal business operations.

Conclusion

· The technical differences between past and present Emotet strains emphasizes the versatility of malicious threat actors and the need for a security solution that is not reliant on signatures.

· Darktrace’s visibility and unique behavioral detection continues to provide visibility to network activities related to the novel Emotet strain without reliance on rules and signatures. Key examples include the C2 connections to new Emotet infrastructure.

· Looking ahead, detection of C2 establishment using suspicious DLLs will prevent further propagation of the Emotet strains across networks.

· Darktrace’s AI detection and response will outpace conventional post compromise research involving the analysis of Emotet strains through static and dynamic code analysis, followed by the implementation of rules and signatures.

Thanks to Paul Jennings and Hanah Darley for their contributions to this blog.

Appendices

Model breaches

· Anomalous Connection / Anomalous SSL without SNI to New External

· Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port

· Anomalous Connection / Multiple Connections to New External TCP Port

· Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

· Anomalous Connection / Multiple HTTP POSTs to Rare Hostname

· Anomalous Connection / Possible Outbound Spam

· Anomalous Connection / Rare External SSL Self-Signed

· Anomalous Connection / Repeated Rare External SSL Self-Signed

· Anomalous Connection / Suspicious Expired SSL

· Anomalous Connection / Suspicious Self-Signed SSL

· Anomalous File / Anomalous Octet Stream (No User Agent)

· Anomalous File / Zip or Gzip from Rare External Location

· Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

· Compromise / Agent Beacon to New Endpoint

· Compromise / Beacon to Young Endpoint

· Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / New or Repeated to Unusual SSL Port

· Compromise / Repeating Connections Over 4 Days

· Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

· Compromise / SSL Beaconing to Rare Destination

· Compromise / Suspicious Beaconing Behaviour

· Compromise / Suspicious Spam Activity

· Compromise / Suspicious SSL Activity

· Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

· Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

· Device / Large Number of Connections to New Endpoints

· Device / Long Agent Connection to New Endpoint

· Device / New User Agent

· Device / New User Agent and New IP

· Device / SMB Session Bruteforce

· Device / Suspicious Domain

· Device / Suspicious SMB Scanning Activity

For Darktrace customers who want to know more about using Darktrace to triage Emotet, refer here for an exclusive supplement to this blog.

References

[1] https://blog.lumen.com/emotet-redux/

[2] https://blogs.vmware.com/security/2022/03/emotet-c2-configuration-extraction-and-analysis.html

[3] https://news.sophos.com/en-us/2022/05/04/attacking-emotets-control-flow-flattening/