What is ClickFix and how does it work?

Amid heightened security awareness, threat actors continue to seek stealthy methods to infiltrate target networks, often finding the human end user to be the most vulnerable and easily exploited entry point.

ClickFix baiting is an exploitation of the end user, making use of social engineering techniques masquerading as error messages or routine verification processes, that can result in malicious code execution.

Since March 2024, the simplicity of this technique has drawn attention from a range of threat actors, from individual cybercriminals to Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups such as APT28 and MuddyWater, linked to Russia and Iran respectively, introducing security threats on a broader scale [1]. ClickFix campaigns have been observed affecting organizations in across multiple industries, including healthcare, hospitality, automotive and government [2][3].

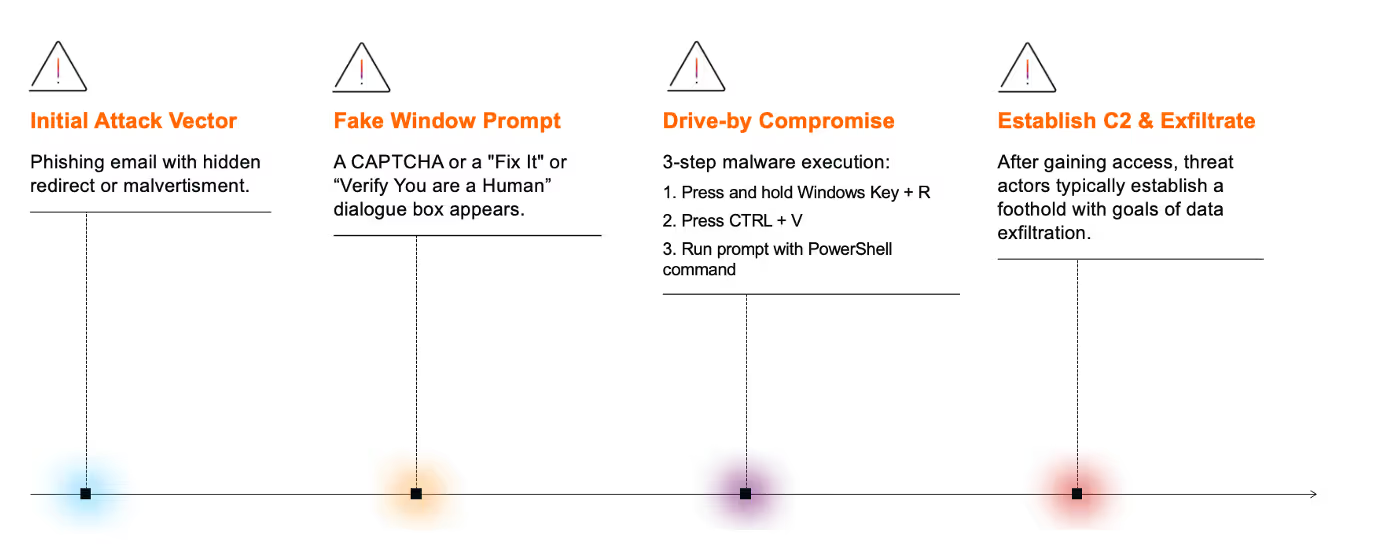

Actors carrying out these targeted attacks typically utilize similar techniques, tools and procedures (TTPs) to gain initial access. These include spear phishing attacks, drive-by compromises, or exploiting trust in familiar online platforms, such as GitHub, to deliver malicious payloads [2][3]. Often, a hidden link within an email or malvertisements on compromised legitimate websites redirect the end user to a malicious URL [4]. These take the form of ‘Fix It’ or fake CAPTCHA prompts [4].

From there, users are misled into believing they are completing a human verification step, registering a device, or fixing a non-existent issue such as a webpage display error. As a result, they are guided through a three-step process that ultimately enables the execution of malicious PowerShell commands:

- Open a Windows Run dialog box [press Windows Key + R]

- Automatically or manually copy and paste a malicious PowerShell command into the terminal [press CTRL+V]

- And run the prompt [press ‘Enter’] [2]

Once the malicious PowerShell command is executed, threat actors then establish command and control (C2) communication within the targeted environment before moving laterally through the network with the intent of obtaining and stealing sensitive data [4]. Malicious payloads associated with various malware families, such as XWorm, Lumma, and AsyncRAT, are often deployed [2][3].

Based on investigations conducted by Darktrace’s Threat Research team in early 2025, this blog highlights Darktrace’s capability to detect ClickFix baiting activity following initial access.

Darktrace’s coverage of a ClickFix attack chain

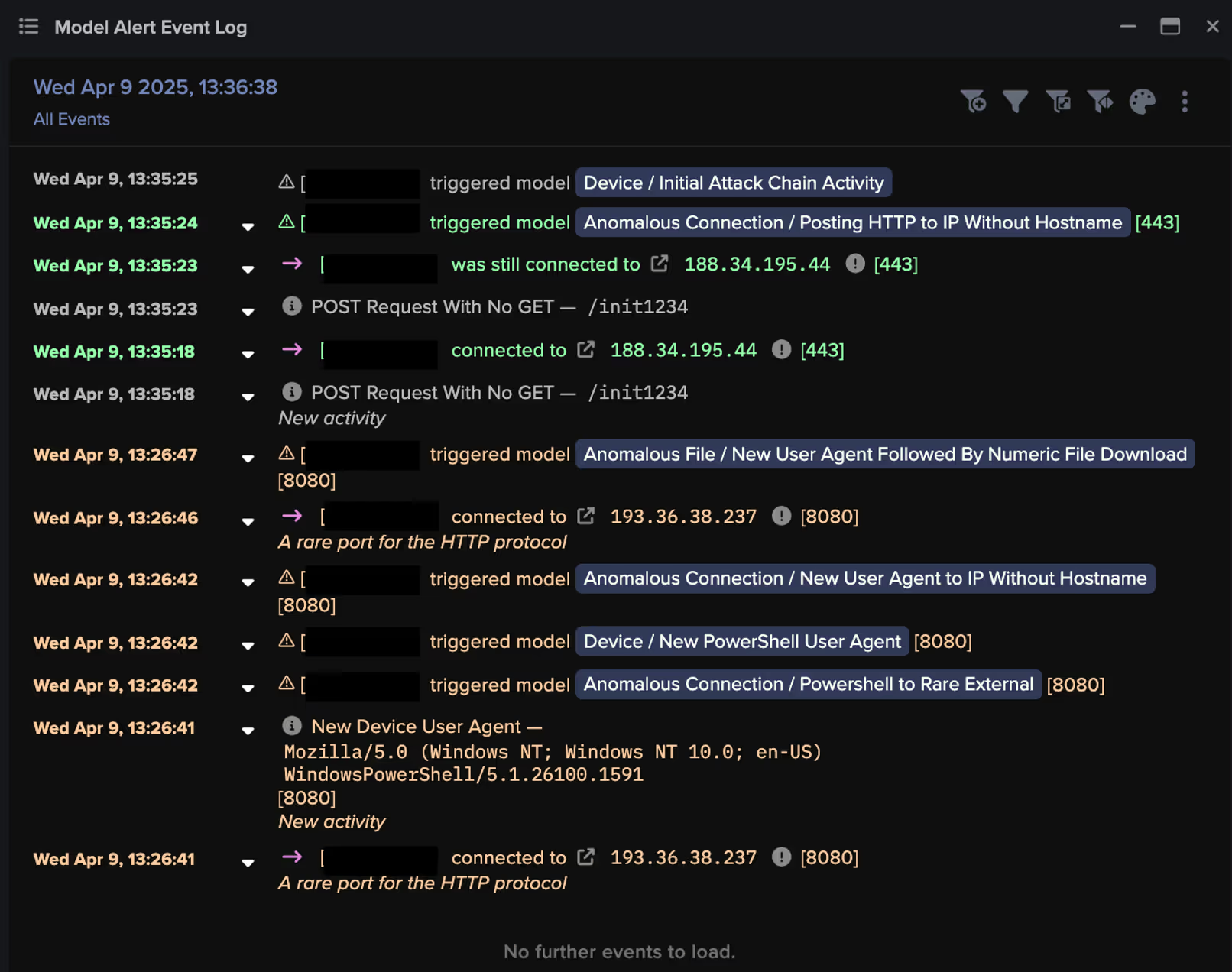

Darktrace identified multiple ClickFix attacks across customer environments in both Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) and the United States. The following incident details a specific attack on a customer network that occurred on April 9, 2025.

Although the initial access phase of this specific attack occurred outside Darktrace’s visibility, other affected networks showed compromise beginning with phishing emails or fake CAPTCHA prompts that led users to execute malicious PowerShell commands.

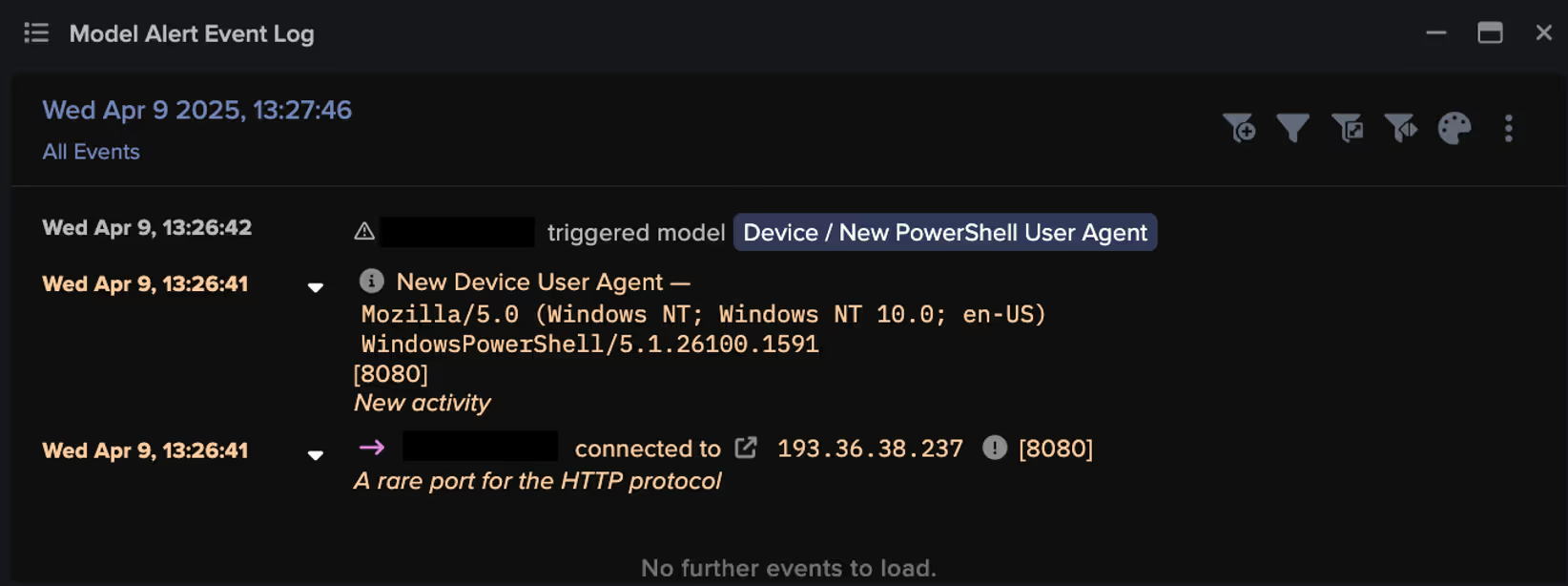

Darktrace’s visibility into the compromise began when the threat actor initiated external communication with their C2 infrastructure, with Darktrace / NETWORK detecting the use of a new PowerShell user agent, indicating an attempt at remote code execution.

Download of Malicious Files for Lateral Movement

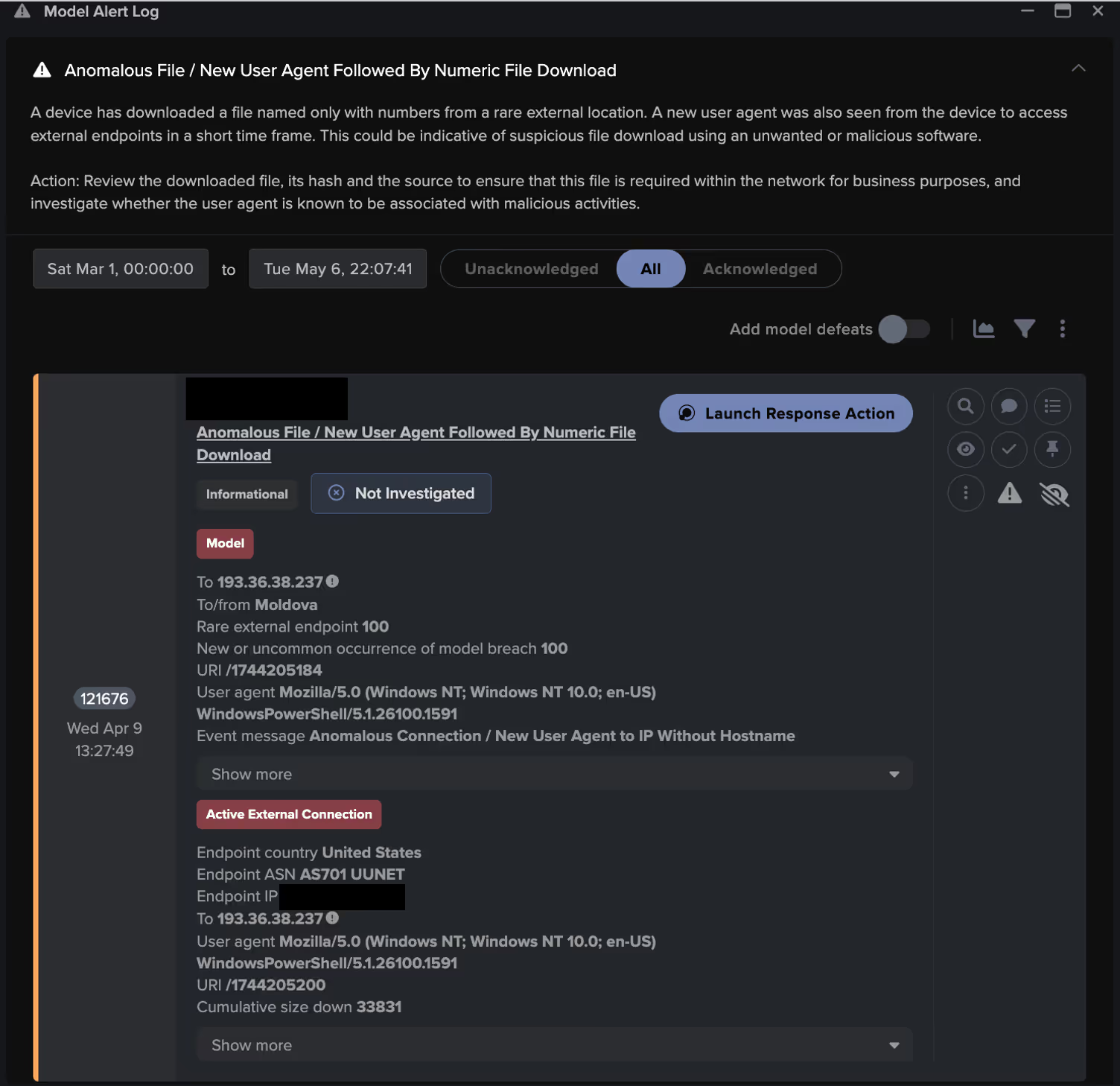

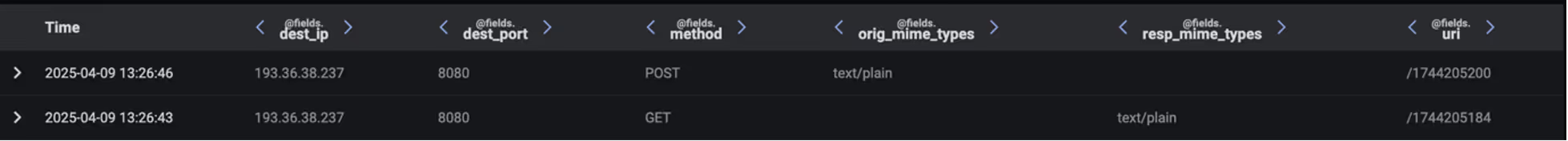

A few minutes later, the compromised device was observed downloading a numerically named file. Numeric files like this are often intentionally nondescript and associated with malware. In this case, the file name adhered to a specific pattern, matching the regular expression: /174(\d){7}/. Further investigation into the file revealed that it contained additional malicious code designed to further exploit remote services and gather device information.

The file contained a script that sent system information to a specified IP address using an HTTP POST request, which also processed the response. This process was verified through packet capture (PCAP) analysis conducted by the Darktrace Threat Research team.

By analyzing the body content of the HTTP GET request, it was observed that the command converts the current time to Unix epoch time format (i.e., 9 April 2025 13:26:40 GMT), resulting in an additional numeric file observed in the URI: /1744205200.

![PCAP highlighting the HTTP GET request that sends information to the specific IP, 193.36.38[.]237, which then generates another numeric file titled per the current time.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/684068fac1b4368f672c17cc_Screenshot%202025-06-04%20at%208.40.32%E2%80%AFAM.avif)

Across Darktrace’s investigations into other customers' affected by ClickFix campaigns, both internal information discovery events and further execution of malicious code were observed.

Data Exfiltration

By following the HTTP stream in the same PCAP, the Darktrace Threat Research Team assessed the activity as indicative of data exfiltration involving system and device information to the same command-and-control (C2) endpoint, , 193.36.38[.]237. This endpoint was flagged as malicious by multiple open-source intelligence (OSINT) vendors [5].

![PCAP highlighting HTTP POST connection with the numeric file per the URI /1744205200 that indicates data exfiltration to 193.36.38[.]237.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/6840694509d92b6220ccf5f1_Screenshot%202025-06-04%20at%208.41.48%E2%80%AFAM.avif)

Further analysis of Darktrace’s Advanced Search logs showed that the attacker’s malicious code scanned for internal system information, which was then sent to a C2 server via an HTTP POST request, indicating data exfiltration

Actions on objectives

Around ten minutes after the initial C2 communications, the compromised device was observed connecting to an additional rare endpoint, 188.34.195[.]44. Further analysis of this endpoint confirmed its association with ClickFix campaigns, with several OSINT vendors linking it to previously reported attacks [6].

In the final HTTP POST request made by the device, Darktrace detected a file at the URI /init1234 in the connection logs to the malicious endpoint 188.34.195[.]44, likely depicting the successful completion of the attack’s objective, automated data egress to a ClickFix C2 server.

Darktrace / NETWORK grouped together the observed indicators of compromise (IoCs) on the compromised device and triggered an Enhanced Monitoring model alert, a high-priority detection model designed to identify activity indicative of the early stages of an attack. These models are monitored and triaged 24/7 by Darktrace’s Security Operations Center (SOC) as part of the Managed Threat Detection service, ensuring customers are promptly notified of malicious activity as soon as it emerges.

Darktrace Autonomous Response

In the incident outlined above, Darktrace was not configured in Autonomous Response mode. As a result, while actions to block specific connections were suggested, they had to be manually implemented by the customer’s security team. Due to the speed of the attack, this need for manual intervention allowed the threat to escalate without interruption.

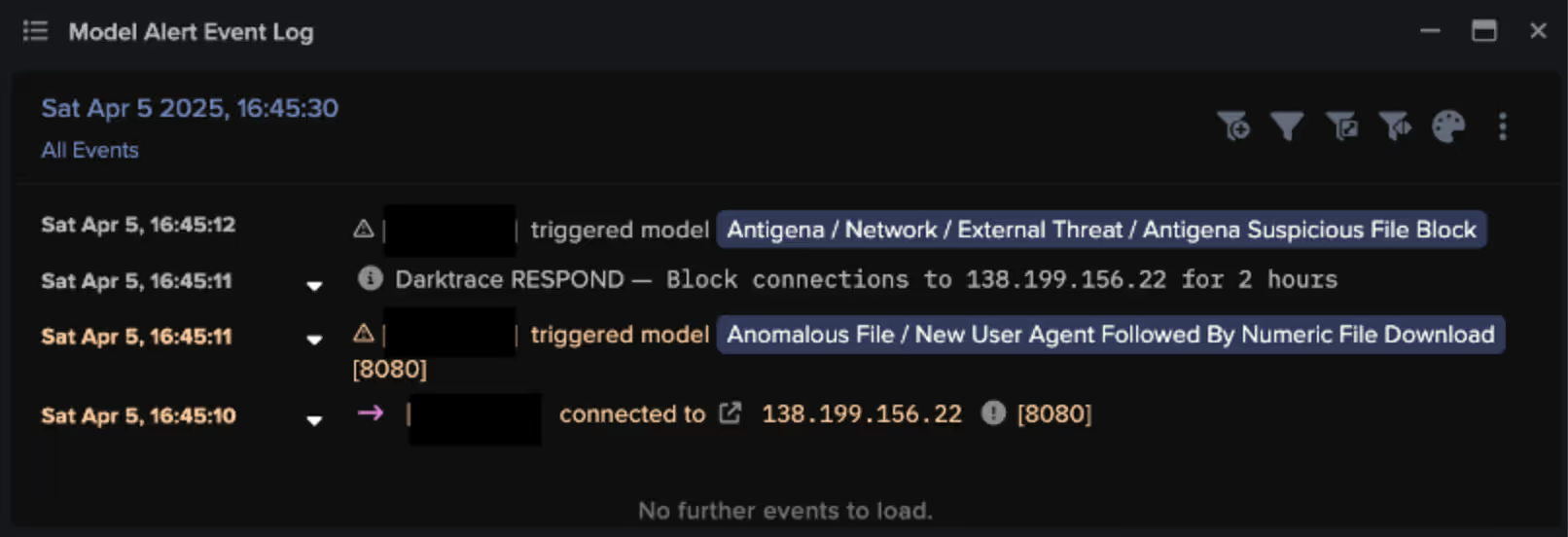

However, in a different example, Autonomous Response was fully enabled, allowing Darktrace to immediately block connections to the malicious endpoint (138.199.156[.]22) just one second after the initial connection in which a numerically named file was downloaded [7].

This customer was also subscribed to our Managed Detection and Response service, Darktrace’s SOC extended a ‘Quarantine Device’ action that had already been autonomously applied in order to buy their security team additional time for remediation.

![Autonomous Response blocked connections to malicious endpoints, including 138.199.156[.]22, 185.250.151[.]155, and rkuagqnmnypetvf[.]top, and also quarantined the affected device. These actions were later manually reinforced by the Darktrace SOC.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/68406a1f723c9d6fda9c5268_Screenshot%202025-06-04%20at%208.45.23%E2%80%AFAM.avif)

Conclusion

ClickFix baiting is a widely used tactic in which threat actors exploit human error to bypass security defenses. By tricking end point users into performing seemingly harmless, everyday actions, attackers gain initial access to systems where they can access and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Darktrace’s anomaly-based approach to threat detection identifies early indicators of targeted attacks without relying on prior knowledge or IoCs. By continuously learning each device’s unique pattern of life, Darktrace detects subtle deviations that may signal a compromise. In this case, Darktrace's Autonomous Response, when operating in a fully autonomous mode, was able to swiftly contain the threat before it could progress further along the attack lifecycle.

Credit to Keanna Grelicha (Cyber Analyst) and Jennifer Beckett (Cyber Analyst)

Appendices

NETWORK Models

- Device / New PowerShell User Agent

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / Powershell to Rare External

- Device / Suspicious Domain

- Device / New User Agent and New IP

- Anomalous File / New User Agent Followed By Numeric File Download (Enhanced Monitoring Model)

- Device / Initial Attack Chain Activity (Enhanced Monitoring Model)

Autonomous Response Models

- Antigena / Network::Significant Anomaly::Antigena Significant Anomaly from Client Block

- Antigena / Network::Significant Anomaly::Antigena Enhanced Monitoring from Client Block

- Antigena / Network::External Threat::Antigena File then New Outbound Block

- Antigena / Network::External Threat::Antigena Suspicious File Block

- Antigena / Network::Significant Anomaly::Antigena Alerts Over Time Block

- Antigena / Network::External Threat::Antigena Suspicious File Block

IoC - Type - Description + Confidence

· 141.193.213[.]11 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 141.193.213[.]10 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 64.94.84[.]217 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 138.199.156[.]22 – IP address – C2 server

· 94.181.229[.]250 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 216.245.184[.]181 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 212.237.217[.]182 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 168.119.96[.]41 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· 193.36.38[.]237 – IP address – C2 server

· 188.34.195[.]44 – IP address – C2 server

· 205.196.186[.]70 – IP address – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· rkuagqnmnypetvf[.]top – Hostname – C2 server

· shorturl[.]at/UB6E6 – Hostname – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· tlgrm-redirect[.]icu – Hostname – Possible C2 Infrastructure

· diagnostics.medgenome[.]com – Hostname – Compromised Website

· /1741714208 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1741718928 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1743871488 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1741200416 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1741356624 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /ttt – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1741965536 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1.txt – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1744205184 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1744139920 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1744134352 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1744125600 – URI – Possible malicious file

· /1[.]php?s=527 – URI – Possible malicious file

· 34ff2f72c191434ce5f20ebc1a7e823794ac69bba9df70721829d66e7196b044 – SHA-256 Hash – Possible malicious file

· 10a5eab3eef36e75bd3139fe3a3c760f54be33e3 – SHA-1 Hash – Possible malicious file

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Tactic – Technique – Sub-Technique

Spearphishing Link - INITIAL ACCESS - T1566.002 - T1566

Drive-by Compromise - INITIAL ACCESS - T1189

PowerShell - EXECUTION - T1059.001 - T1059

Exploitation of Remote Services - LATERAL MOVEMENT - T1210

Web Protocols - COMMAND AND CONTROL - T1071.001 - T1071

Automated Exfiltration - EXFILTRATION - T1020 - T1020.001

References

[3] https://cyberresilience.com/threatonomics/understanding-the-clickfix-attack/

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/193.36.38.237/detection

[6] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/188.34.195.44/community

[7] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/138.199.156.22/detection

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)