Introduction: Meeten malware

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have identified a new sophisticated scam targeting people who work in Web3. The campaign includes cryptostealer Realst that has both macOS and Windows variants, and has been active for around four months. Research shows that the threat actors behind the malware have set up fake companies using AI to make them increase legitimacy. The company, which is currently going by the name “Meetio”, has cycled through various names over the past few months. In order to appear as a legitimate company, the threat actors created a website with AI-generated content, along with social media accounts. The company reaches out to targets to set up a video call, prompting the user to download the meeting application from the website, which is Realst info stealer.

Meeten

“Meeten” is the application that is attempting to scam users into downloading an information stealer. The company regularly changes names, and has also gone by Clusee[.]com, Cuesee, Meeten[.]gg, Meeten[.]us, Meetone[.]gg and is currently going by the name Meetio. In order to gain credibility, the threat actors set up full company websites, with AI-generated blog and product content and social media accounts including Twitter and Medium.

Based on public reports from targets (withheld from this post for privacy), the scam is conducted in multiple ways. In one reported instance, a user was contacted on Telegram by someone they knew who wanted to discuss a business opportunity and to schedule a call. However, the Telegram account was created to impersonate a contact of the target. Even more interestingly, the scammer sent an investment presentation from the target’s company to him, indicating a sophisticated and targeted scam. Other reports of targeted users report being on calls related to Web3 work, downloading the software and having their cryptocurrency stolen.

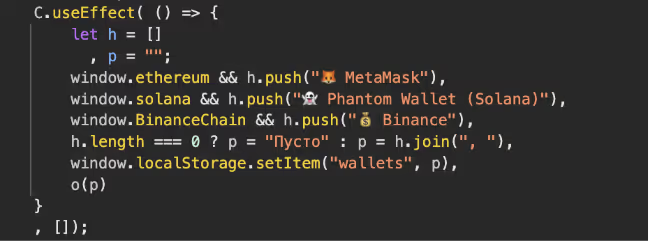

After initial contact, the target would be directed to the Meeten website to download the product. In addition to hosting information stealers, the Meeten websites contain Javascript to steal cryptocurrency that is stored in web browsers, even before installing any malware.

Technical analysis

macOS version

Name: CallCSSetup.pkg

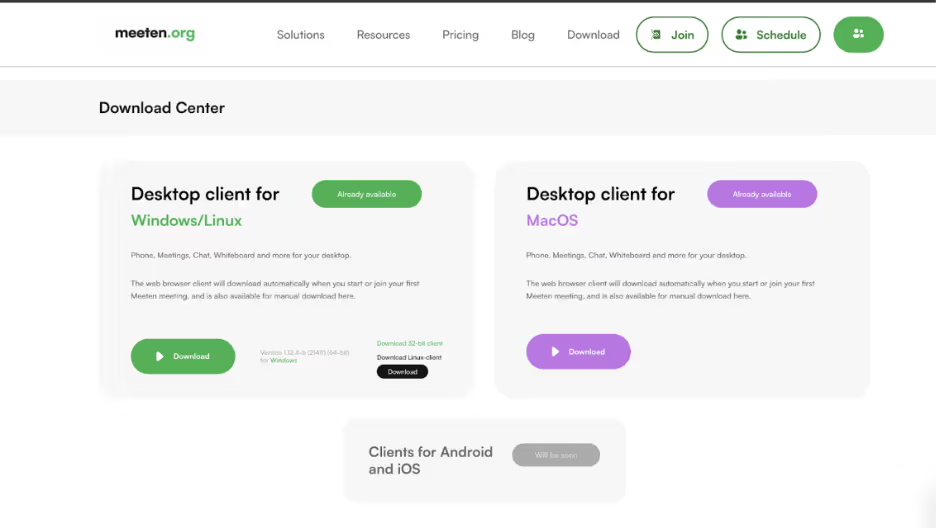

Once the victim is directed to the “Meeten” website, the downloads page offers macOS or Windows/Linux. In this iteration of the website, all download links lead to the macOS version. The package file contains a 64-bit binary named “fastquery”, however other versions of the malware are distributed as a DMG with a multi-arch binary. The binary is written in Rust, with the main functionality being information stealing.

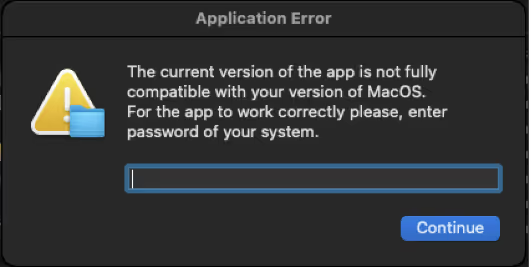

When opened, two error messages appear. The first one states “Cannot connect to the server. Please reinstall or use a VPN.” with a continue button. Osascript, the macOS command-line tool for running AppleScript and JavaScript is used to prompt the user for their password, as commonly seen in macOS malware. [1]

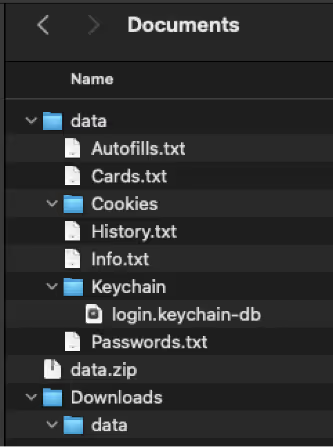

The malware iterates through various data stores, grabs sensitive information, creates a folder where the data is stored, and then exfiltrates the data as a zip.

Realst Stealer looks for and exfiltrates if available:

- Telegram credentials

- Banking card details

- Keychain credentials

- Browser cookies and autofill credentials from Google Chrome, Opera, Brave, Microsoft Edge, Arc, CocCoc and Vivaldi

- Ledger Wallets

- Trezor Wallets

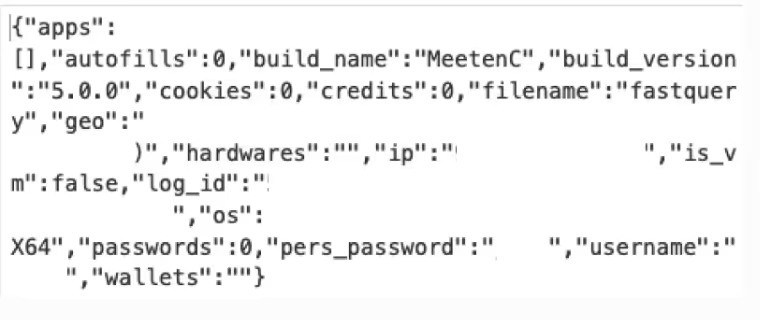

The data is sent to 139[.]162[.]179.170:8080/new_analytics with “log_id”, “anal_data” and “archive”. This contains the zip data to be exfiltrated along with analytics that include build name, build version, with system information.

Build information is also sent to 139[.]162[.]179.170:8080/opened along with metrics sent to /metrics. Following the data exfiltration, the created temporary directories are removed from the system.

Windows version

Name: MeetenApp.exe

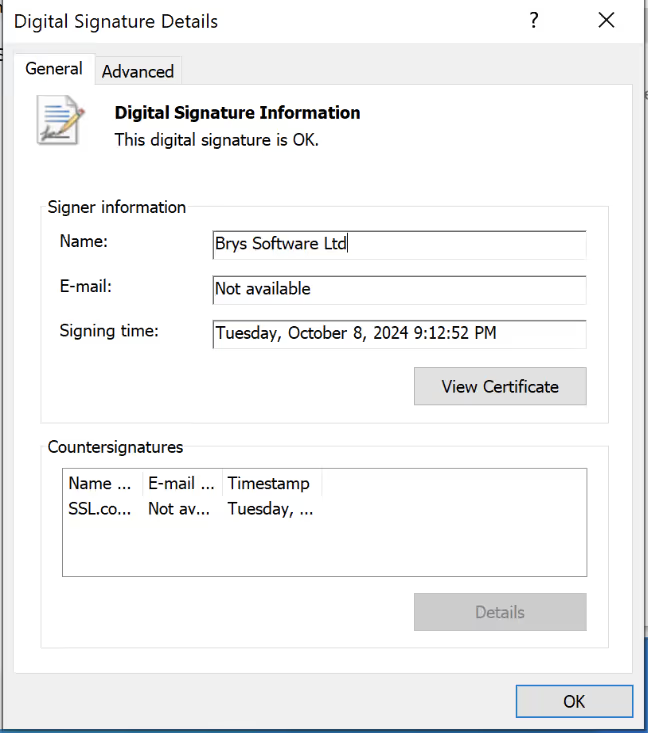

While analyzing the macOS version of Meeten, Cado Security Labs identified a Windows version of the malware. The binary, “MeetenApp.exe” is a Nullsoft Scriptable Installer System (NSIS) file, with a legitimate signature from “Brys Software” that has likely been stolen.

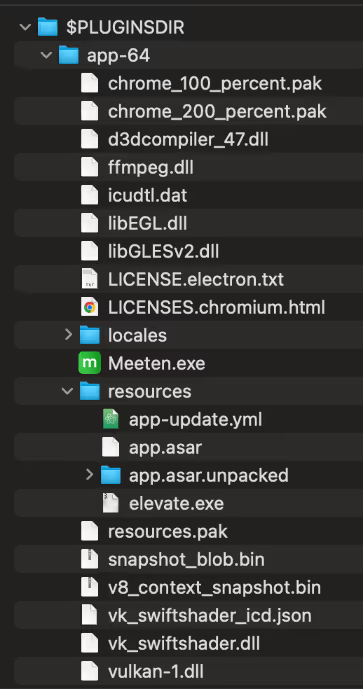

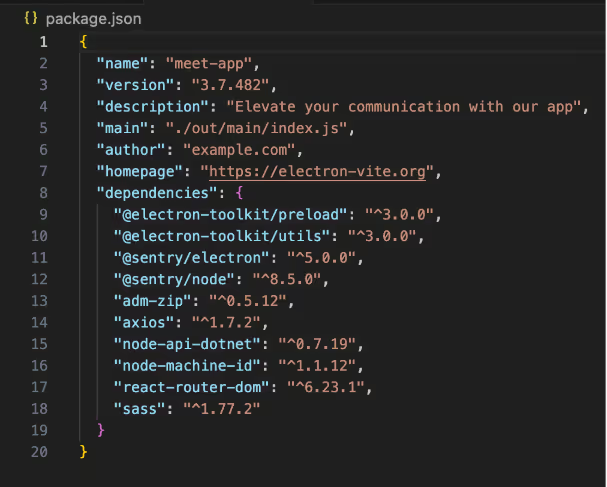

After extracting the files from the installer, there are two folders $PLUGINDIR and $R0. Inside $PLUGINDIR is a 7zip archive named “app-64” that contains resources, assets, binaries and an app.asar file, indicating this is an Electron application. Electron applications are built on the Electron framework that is used to develop cross-platform desktop applications with web languages such as Javascript. App.asar files are used by Electron runtime, and is a virtual file system containing application code, assets, and dependencies.

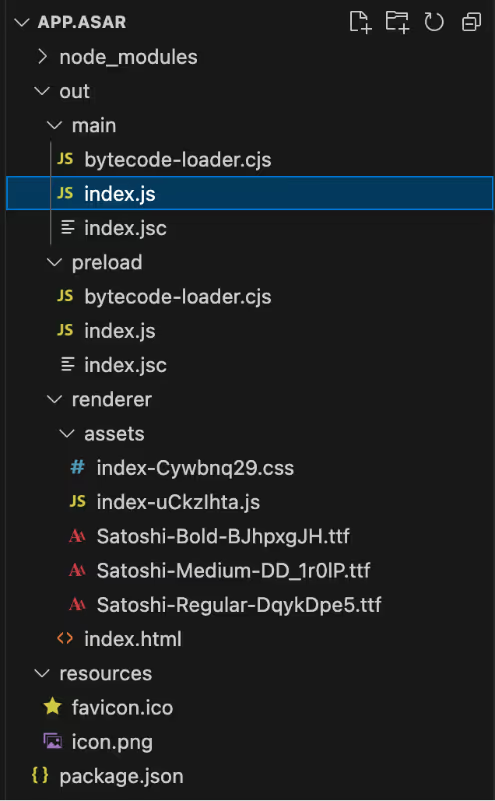

After extracting the contents of app.asar, we can see the main script points to index.js containing:

"use strict";

require("./bytecode-loader.cjs");

require("./index.jsc"); Both of these are Bytenode Compiled Javascript files. Bytenode is a tool that compiles JavaScript code into V8 bytecode, allowing the execution of JavaScript without exposing the source code. The bytecode is a low-level representation of the JavaScript code that can be executed by the V8 JavaScript engine which powers Node.js. Since the Javascript is compiled, reverse engineering of the files is more difficult, and less likely to be detected by security tools.

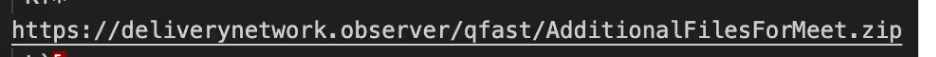

While the file is compiled, there is still some information we can see as plain text. Similarly to the macOS version, a log with system information is sent to a remote server. A secondary password protected archive , “AdditionalFilesForMeet.zip” is retrieved from deliverynetwork[.]observer into a temporary directory “temp03241242”.

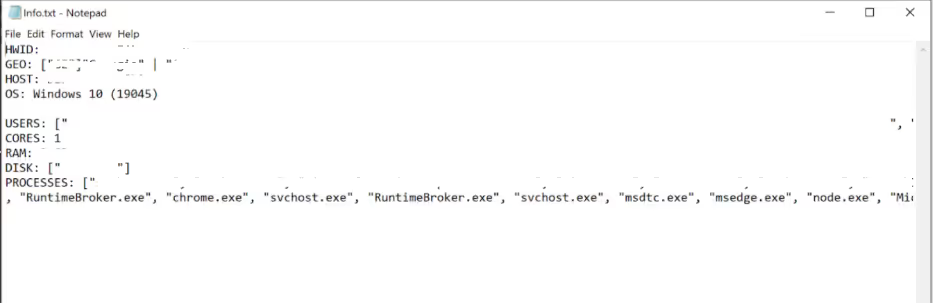

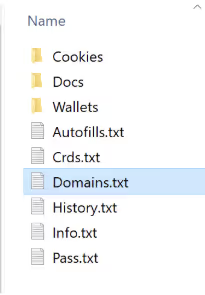

From AdditionalFilesForMeet.zip is a binary named “MicrosoftRuntimeComponentsX86.exe” This binary gathers system information including HWID, geo IP, hostname, OS, users, cores, RAM, disk size and running processes.

This data is sent to 172[.]104.133.212/opened, along with the build version of Meeten.

An additional payload is retrieved “UpdateMC.zip” from “deliverynetwork[.]observer/qfast” into AppData/Local/Temp. The archive file extracts to UpdateMC.exe.

UpdateMC

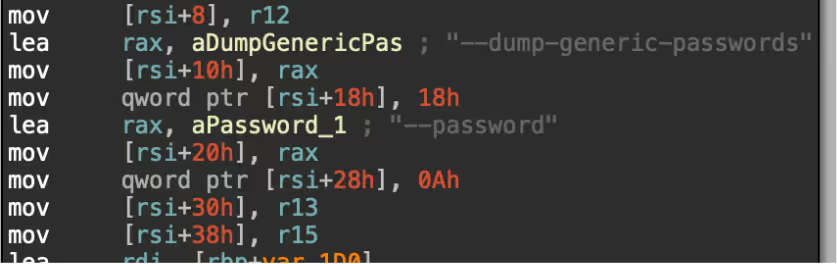

UpdateMC.exe is a Rust-based binary, with similar functionality to the macOS version. The stealer searches in various data stores to collect and exfiltrate sensitive data as a zip. Meeten has the ability to steal data from:

- Telegram credentials

- Banking card details

- Browser cookies, history and autofill credentials from Google Chrome, Opera, Brave, Microsoft Edge, Arc, CocCoc and Vivaldi

- Ledger Wallets

- Trezor Wallets

- Phantom Wallets

- Binance Wallets

The data is stored inside a folder named after the users’ HWID inside AppData/Local/Temp directory before being exfiltrated to 172[.]104.133.212.

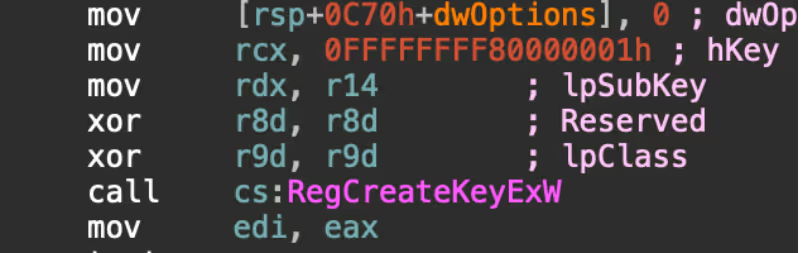

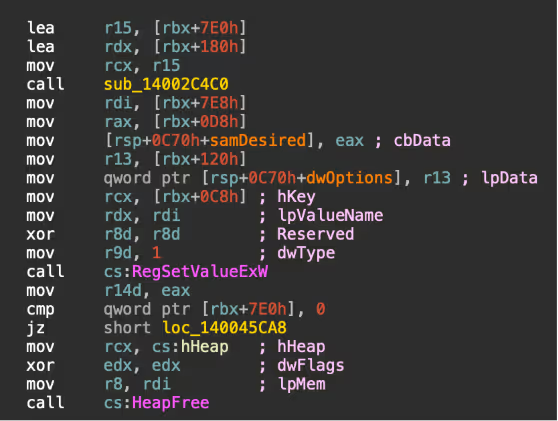

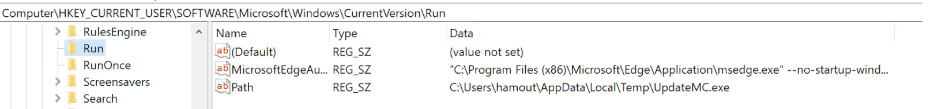

For persistence, a registry key is added to HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run to ensure that the stealer is run each time the machine is started.

Key takeaways

This blog highlights a sophisticated campaign that uses AI to social engineer victims into downloading low detected malware that has the ability to steal financial information. Although the use of malicious Electron applications is relatively new, there has been an increase of threat actors creating malware with Electron applications. [2] As Electron apps become increasingly common, users must remain vigilant by verifying sources, implementing strict security practices, and monitoring for suspicious activity.

While much of the recent focus has been on the potential of AI to create malware, threat actors are increasingly using AI to generate content for their campaigns. Using AI enables threat actors to quickly create realistic website content that adds legitimacy to their scams, and makes it more difficult to detect suspicious websites. This shift shows how AI can be used as a powerful tool in social engineering. As a result, users need to exercise caution when being approached about business opportunities, especially through Telegram. Even if the contact appears to be an existing contact, it is important to verify the account and always be diligent when opening links.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

http://172[.]104.133.212:8880/new_analytics

http://172[.]104.133.212:8880/opened

http://172[.]104.133.212:8880/metrics

http://172[.]104.133.212:8880/sede

139[.]162[.]179.170:8080

deliverynetwork[.]observer/qfast/UpdateMC.zip

deliverynetwork[.]observer/qfast/AdditionalFilesForMeet.zip

www[.]meeten.us

www[.]meetio.one

www[.]meetone.gg

www[.]clusee.com

199[.]247.4.86

File / md5

CallCSSetup.pkg 9b2d4837572fb53663fffece9415ec5a

Meeten.exe 6a925b71afa41d72e4a7d01034e8501b

UpdateMC.exe 209af36bb119a5e070bad479d73498f7

MicrosoftRuntimeComponentsX64.exe d74a885545ec5c0143a172047094ed59

CluseeApp.pkg 09b7650d8b4a6d8c8fbb855d6626e25d

MITRE ATT&CK

Technique name / ID

T1204 User Execution

T1555.001 Credentials From Password Stores: Keychain

T1555.003 Credentials From Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers

T1539 Steal Web Session Cookie

T1217 Browser Information Discovery

T1082 System Information Discovery

T1016 System Network Configuration Discovery

T1033 System Owner/User Discovery

T1005 Data from Local System

T1074 Local Data Staging

T1071.001 Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

T1041 Exfiltration Over C2 Channel

T1657 Financial Theft

T1070.004 File Deletion

T1553.001 Subvert Trust Controls: Gatekeeper Bypass

T1553.002 Subvert Trust Controls: Code Signing

T1547.001 Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Folder

T1497.001 Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion: System Checks

T1058.001 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Powershell

T1016 Network Configuration Discovery

T1007 System Service Discovery

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)