Introduction: P2PInfect

Since July 2023, researchers at Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have been monitoring and reporting on the rapid growth of a cross-platform botnet, named “P2Pinfect”. As the name suggests, the malware - written in Rust - acts as a botnet agent, connecting infected hosts in a peer-to-peer topology. In early samples, the malware exploited Redis for initial access - a relatively common technique in cloud environments.

There are a number of methods for exploiting Redis servers, several of which appear to be utilized by P2Pinfect. These include exploitation of CVE-2022-0543 [1] - a sandbox escape vulnerability in the LUA scripting language (reported by Unit42 [2]), and, as reported previously by Cado Security Labs, an unauthorized replication attack resulting in the loading of a malicious Redis module.

Researchers have since encountered a new variant of the malware, specifically targeting embedded devices based on 32-bit MIPS processors, and attempting to brute force SSH access to these devices. It’s highly likely that by targeting MIPS, the P2Pinfect developers intend to infect routers and IoT devices with the malware. Use of MIPS processors is common for embedded devices and the architecture has been previously targeted by botnet malware, including high-profile families like Mirai [3], and its variants/derivatives.

Not only is this an interesting development in that it demonstrates a widening of scope for the developers behind P2Pinfect (more supported processor architectures equals more nodes in the botnet itself), but the MIPS32 sample includes some notable defense evasion techniques.

This, combined with the malware’s utilization of Rust (aiding cross-platform development) and rapid growth of the botnet itself, reinforces previous suggestions that this campaign is being conducted by a sophisticated threat actor.

Initial access

Cado researchers encountered the MIPS variant of P2Pinfect after triaging files uploaded via SFTP and SCP to a SSH honeypot. Although earlier variants had been observed scanning for SSH servers, and attempting to propagate the malware via SSH as part of its worming procedure, researchers had yet to observe successful implantation of a P2Pinfect sample using this method - until now.

In keeping with similar botnet families, P2Pinfect includes a number of common username/password pairs embedded within the MIPS binary itself. The malware will then iterate through these pairs, initiating a SSH connection with servers identified during the scanning phase to conduct a brute force attack.

It was assumed that SSH would be the primary method of propagation for the MIPS variant, due to routers and other embedded devices being more likely to utilize SSH. However, additional research shows that it is in fact possible to run the Redis server on MIPS. This is achievable via an OpenWRT package named redis-server. [4]

It is unclear what use-case running Redis on an embedded MIPS device solves, or whether it is commonly encountered in the wild. If such a device is compromised by P2Pinfect and has the Redis-server package installed, it is perfectly feasible for that node to then be used to compromise new peers via one of the reported P2Pinfect attack patterns, involving exploitation of Redis or SSH brute-forcing.

Static analysis

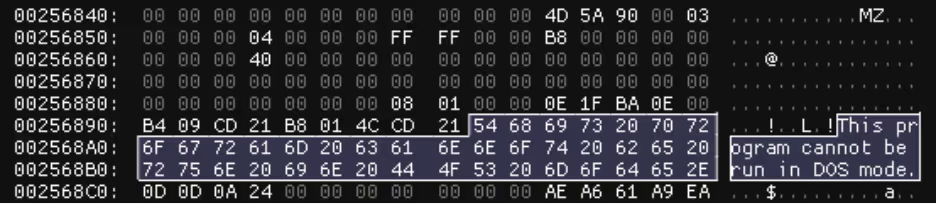

The MIPS variant of P2Pinfect is a 32-bit, statically-linked, ELF binary with stripped debug information. Basic static analysis revealed the presence of an additional ELF executable, along with a 32-bit Windows DLL in the PE32 format - more on this later.

This piqued the interest of Cado analysts, as it is unusual to encounter a compiled ELF with an embedded DLL. Consequently, it was a defining feature of the original P2Pinfect samples.

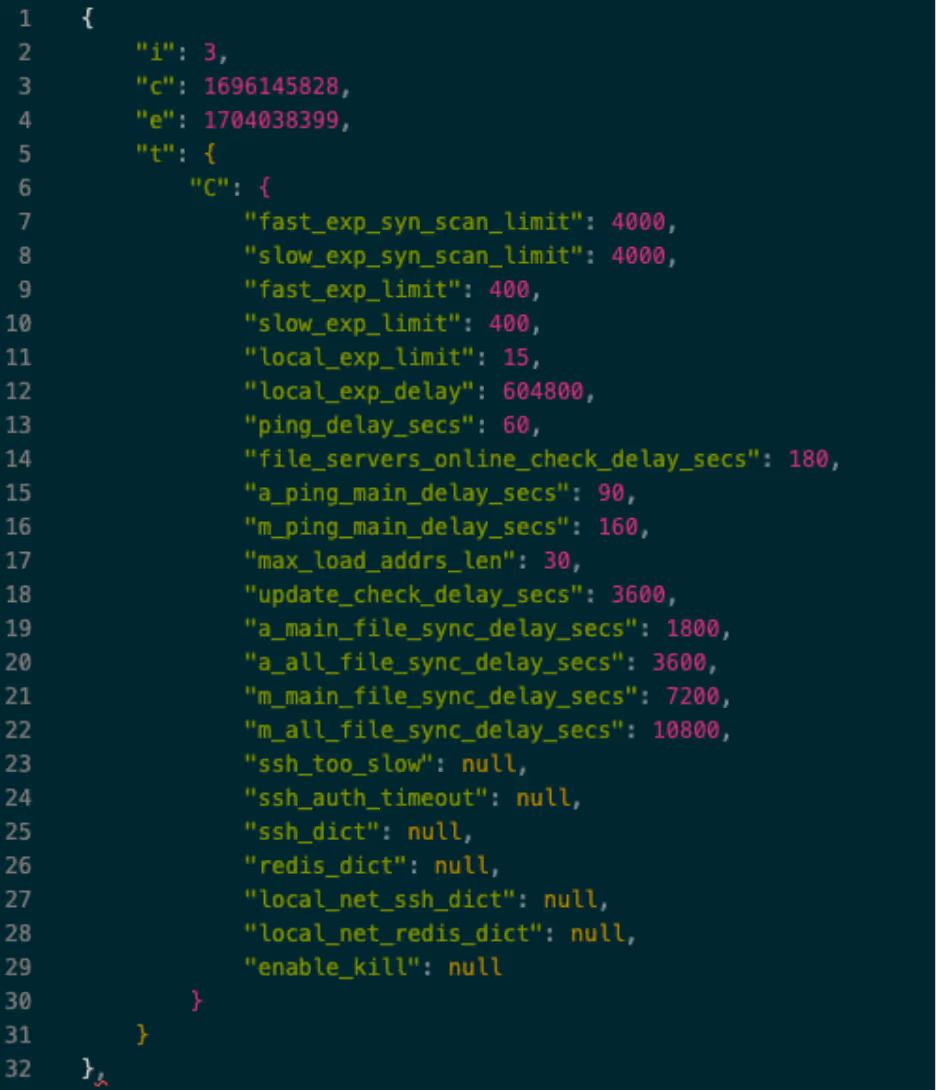

Further analysis of the host executable revealed a structure named “BotnetConf” with members consistent in naming with the original P2Pinfect samples.

As the name suggests, this structure defines the configuration of the malware itself, whilst also storing the IP addresses of nodes identified during the SSH and Redis scans. This, in combination with the embedded ELF and DLL, along with the use of the Rust programming language allowed for positive attribution of this sample to the P2Pinfect family.

Updated evasion - consulting tracerpid

One of the more interesting aspects of the MIPS sample was the inclusion of a new evasion technique. Shortly after execution, the sample calls fork() to spawn a child process.

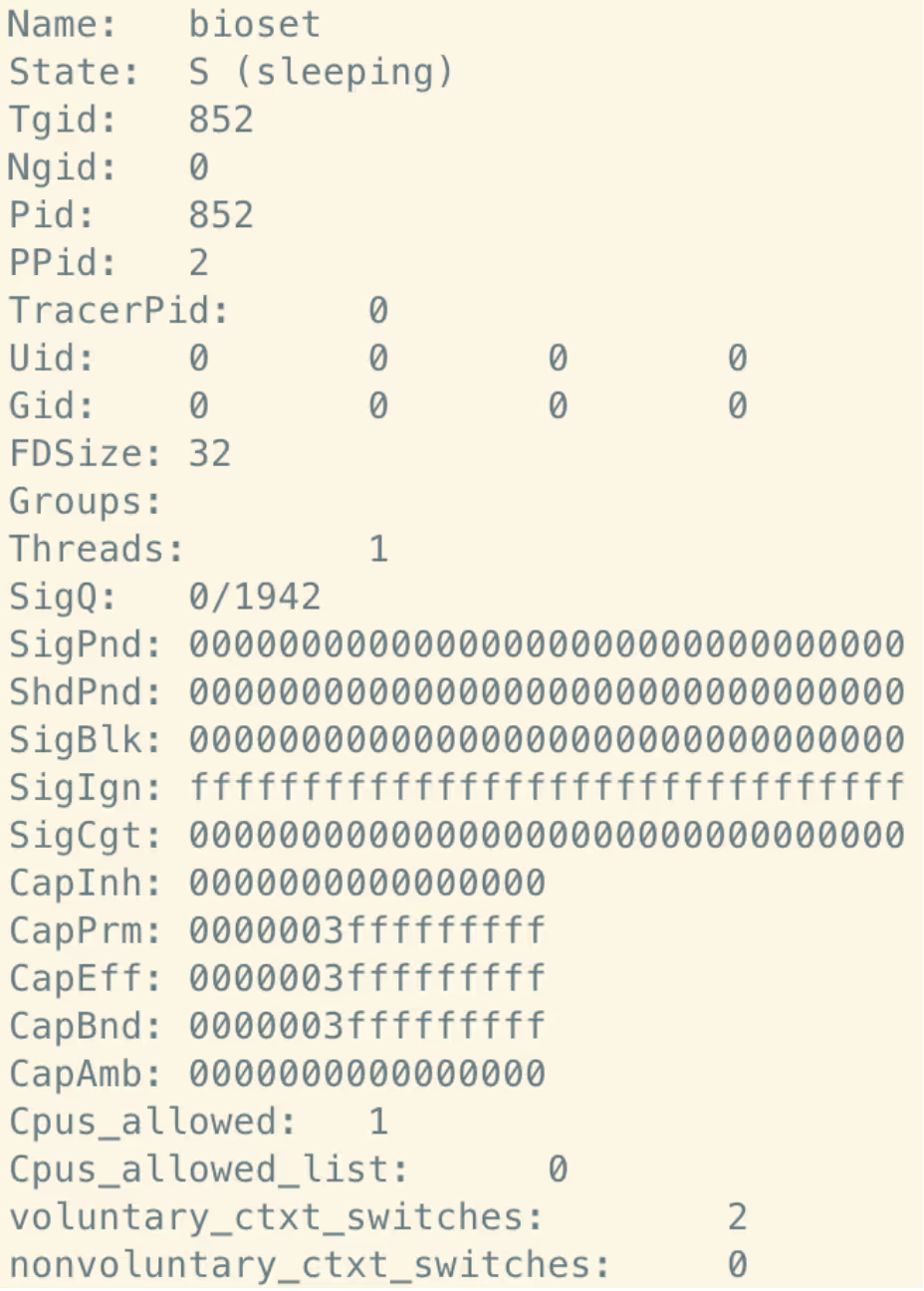

The child process then proceeds to access /proc using openat(), determines its own Process Identifier (PID) using the Linux getpid() syscall, and then uses this PID to consult the relevant /proc subdirectory and read the status file within that. Note that this is likely achieved in the source code by resolving the symbolic link at /proc/self/status.

/proc/<pid>/status contains human-readable metadata and other information about the process itself, including memory usage and the name of the command currently being run. Importantly, the status file also contains a field TracerPID:. This field is assigned a value of 0 if the current process is not being traced by dynamic analysis tools, such as strace and ltrace.

If this value is non-zero, the MIPS variant of P2Pinfect determines that it is being analyzed and will immediately terminate both the child process and its parent.

read(5, "Name:\tmips_embedded_p\nUmask:\t002", 32) = 32

read(5, "2\nState:\tR (running)\nTgid:\t975\nN", 32) = 32

read(5, "gid:\t0\nPid:\t975\nPPid:\t1\nTracerPid:\t971\nUid:\t0\t0\t0\t0\nGid:\t0\t0\t0\t0", 64) = 64

read(5, "\nFDSize:\t32\nGroups:\t0 \nNStgid:\t975\nNSpid:\t975\nNSpgid:\t975\nNSsid:\t975\nVmPeak:\t 3200 kB\nVmSize:\t 3192 kB\nVmLck:\t 0 kB\n", 128) = 128

read(5, "VmPin:\t 0 kB\nVmHWM:\t 1564 kB\nVmRSS:\t 1560 kB\nRssAnon:\t 60 kB\nRssFile:\t 1500 kB\nRssShmem:\t 0 kB\nVmData:\t 108 kB\nVmStk:\t 132 kB\nVmExe:\t 2932 kB\nVmLib:\t 8 kB\nVmPTE:\t 16 kB\nVmSwap:\t 0 kB\nCoreDumping:\t0\nThre", 256) = 256

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x77ff1000

read(5, "ads:\t1\nSigQ:\t0/1749\nSigPnd:\t00000000000000000000000000000000\nShdPnd:\t00000000000000000000000000000000\nSigBlk:\t00000000000000000000000000000000\nSigIgn:\t00000000000000000000000000001000\nSigCgt:\t00000000000000000000000000000600\nCapInh:\t0000000000000000\nCapPrm:\t0000003fffffffff\nCapEff:\t0000003fffffffff\nCapBnd:\t0000003fffffffff\nCapAmb:\t0000000000000000\nNoNewPrivs:\t0\nSeccomp:\t0\nSpeculation_Store_Bypass:\tunknown\nCpus_allowed:\t1\nCpus_allowed_list:\t0\nMems_allowed:\t1\nMems_allowed_list:\t0\nvoluntary_ctxt_switches:\t92\nn", 512) = 512

mmap2(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x77fef000

munmap(0x77ff1000, 4096) = 0

read(5, "onvoluntary_ctxt_switches:\t0\n", 1024) = 29

read(5, "", 995) = 0

close(5) = 0

munmap(0x77fef000, 8192) = 0

sigaltstack({ss_sp=NULL, ss_flags=SS_DISABLE, ss_size=8192}, NULL) = 0

munmap(0x77ff4000, 12288) = 0

exit_group(-101) = ?

+++ exited with 155 +++ Strace output demonstrating TracerPid evasion technique

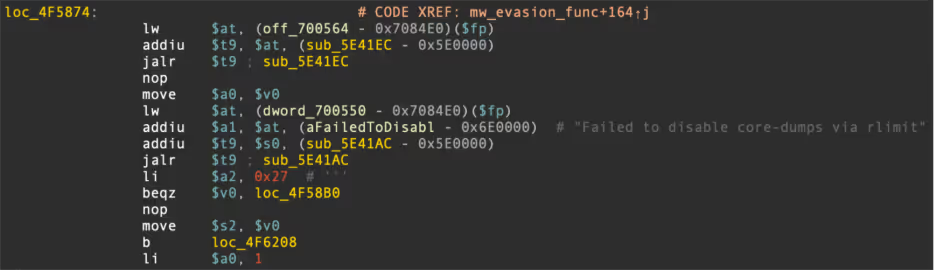

Updated evasion - disabling core dumps

Interestingly, the sample will also attempt to disable Linux core dumps. This is likely used as an anti-forensics procedure as the memory regions written to disk as part of the core dump can often contain internal information about the malware itself. In the case of P2Pinfect, this would likely include information such as IP addresses of connected peers and the populated BotnetConf structure mentioned previously.

It is also possible that the sample prevents core dumps from being created to protect the availability of the MIPS device itself. Low-powered embedded devices are unlikely to have much local storage available and core dumps could quickly fill what little storage they do have, affecting performance of the device itself.

This procedure can be observed during dynamic analysis, with the binary utilising the prctl() syscall and passing the parameters PR_SET_DUMPABLE, SUID_DUMP_DISABLE.

munmap(0x77ff1000, 4096) = 0

prctl(PR_SET_DUMPABLE, SUID_DUMP_DISABLE) = 0

prlimit64(0, RLIMIT_CORE, {rlim_cur=0, rlim_max=0}, NULL) = 0 Example strace output demonstrating disabling of core dumps

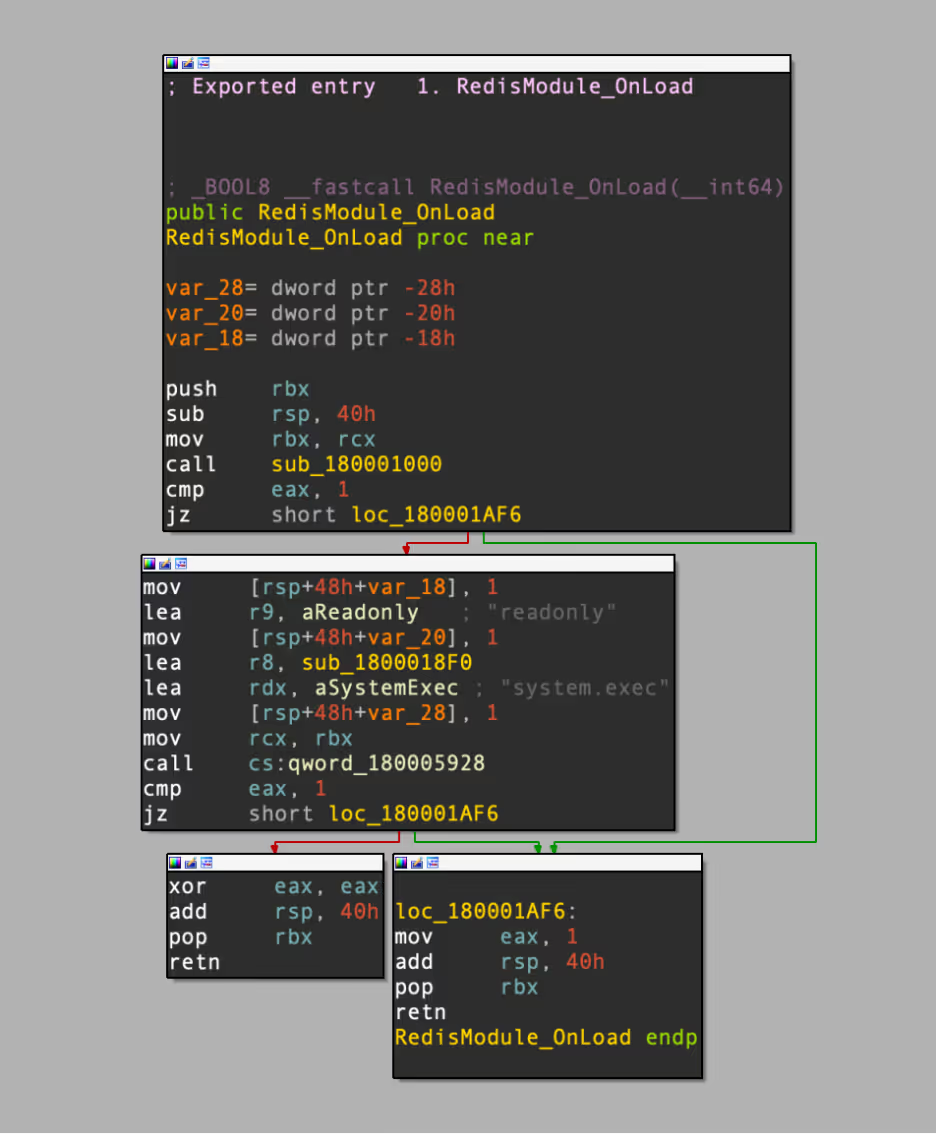

Embedded DLL

As mentioned in the Static Analysis section, the MIPS variant of P2Pinfect includes an embedded 64-bit Windows DLL. This DLL acts as a malicious loadable module for Redis, implementing the system.exec functionality to allow the running of shell commands on a compromised host.

This is consistent with the previous examples of P2Pinfect, and demonstrates that the intention is to utilize MIPS devices for the Redis-specific initial access attack patterns mentioned throughout this blog.

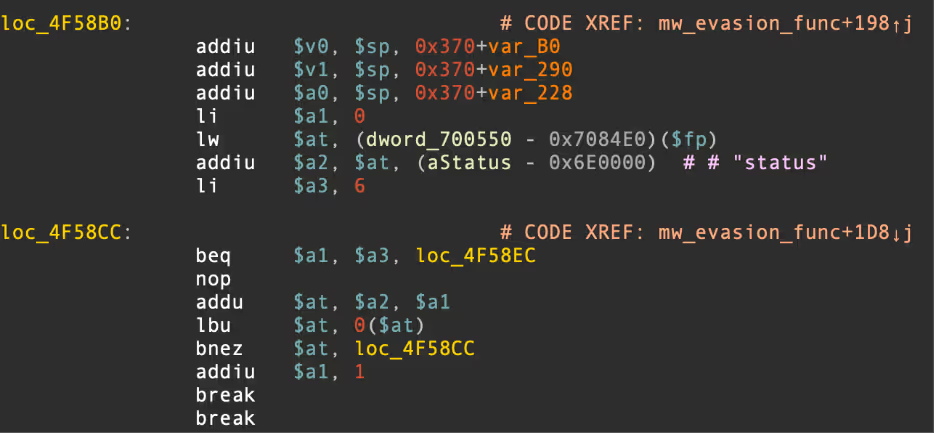

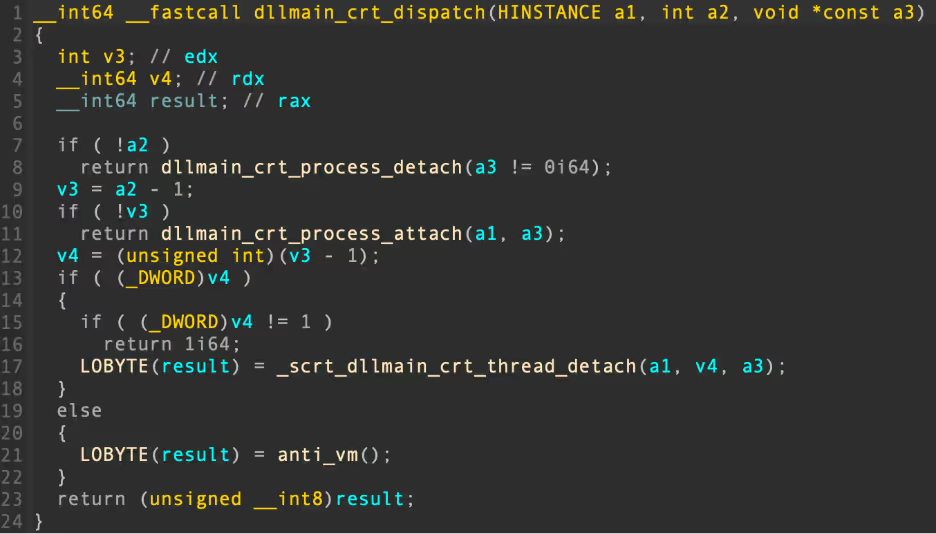

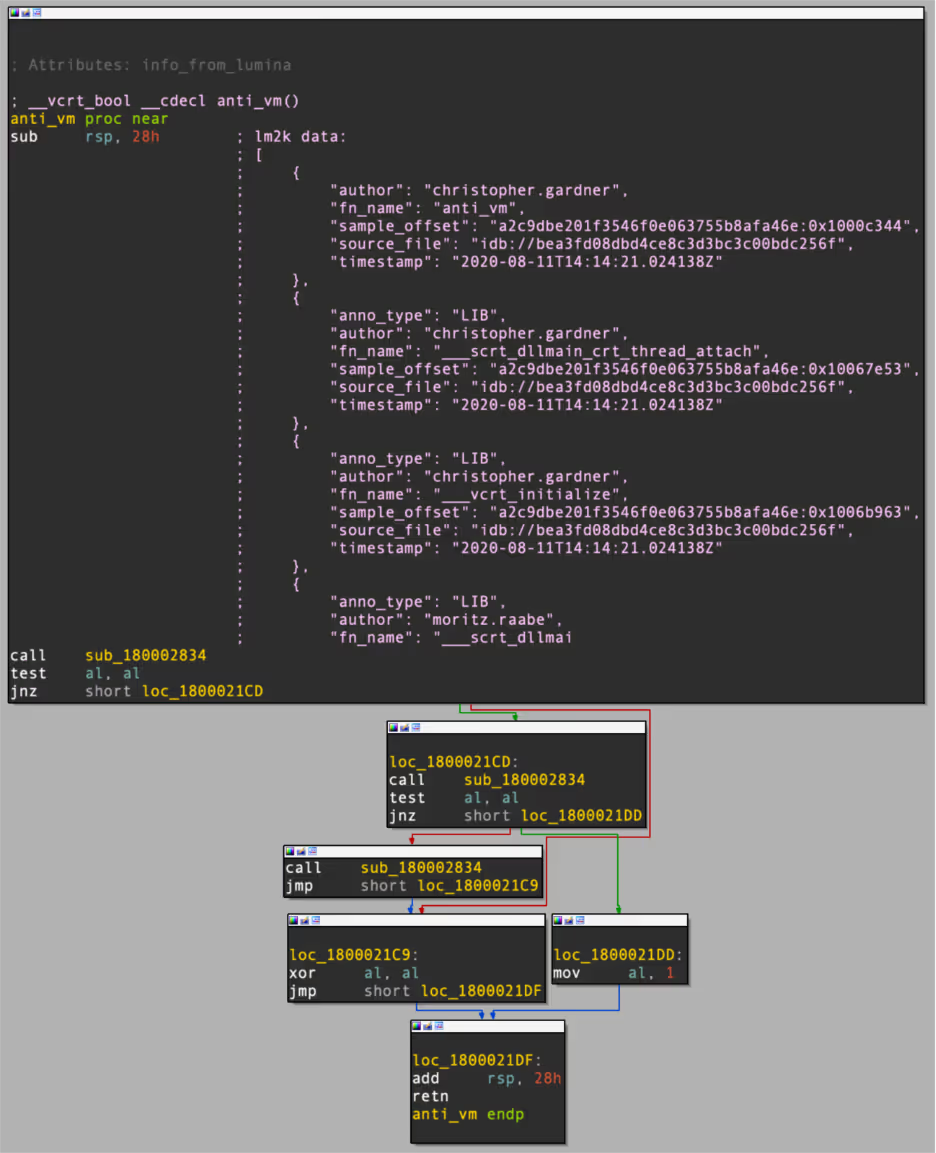

Interestingly, this embedded DLL also includes a Virtual Machine (VM) evasion function, demonstrating the lengths that the P2Pinfect developers have taken to hinder the analysis process. In the DLLs main function, a call can be observed to a function helpfully labelled anti_vm by IDAs Lumina feature.

Viewing the function itself, it can be seen that researchers Christopher Gardner and Moritz Raabe have identified it as a known VM evasion method in other malware samples.

Conclusion

P2Pinfect’s continued evolution and broadened targeting appear to be the utilization of a variety of evasion techniques demonstrate an above-average level of sophistication when it comes to malware development. This is a botnet that will continue to grow until it’s properly utilized by its operators.

While much of the functionality of the MIPS variant is consistent with the previous variants of this malware, the developer’s efforts in making both the host and embedded executables as evasive as possible show a continued commitment to complicating the analysis procedure. The use of anti-forensics measures such as the disabling of core dumps on Linux systems also supports this.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

Files SHA256

MIPS ELF 8b704d6334e59475a578d627ae4bcb9c1d6987635089790350c92eafc28f5a6c

Embedded DLL Redis Module d75d2c560126080f138b9c78ac1038ff2e7147d156d1728541501bc801b6662f

References:

[1] https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2022-0543

[2] https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/peer-to-peer-worm-p2pinfect/

[3] https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/mirai-variant-iz1h9/

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)