Industrial IoT (IIoT) devices are a pressing concern for security teams. Companies invest large sums of money to keep cyber-criminals out of industrial systems, but what happens when the hacker is already inside? Gateways and legacy security tools generally sit at the border of an organization and are designed to stop external threats, but are less effective once the threat is already inside. During this period, cyber-criminals carry out further reconnaissance, tamper with PLC settings, and subtly disrupt the production process.

Darktrace recently detected a series of pre-existing infections in Industrial IoT (IIoT) devices at a manufacturing firm in the EMEA region. The organization already had Darktrace in place in one area of the environment, but after seeing how the AI could successfully detect zero-day vulnerabilities and threats, they expanded the deployment, allowing Darktrace to actively monitor and defend interactions among its 5,000 devices, and dramatically improving visibility.

An unknown emerging threat was identified by Darktrace’s Industrial Immune System on multiple machines within hours of Darktrace being active in the environment. By casting light on this previously unknown threat, Darktrace enabled the customer to perform full incident response and threat investigation, before the attacker was able to cause any serious damage to the company.

Though it is unclear how long the devices had been infected, it is likely to have been first introduced manually via an infected USB. The affected endpoints were being used as part of a continuous production process and could not be installed with endpoint protection.

The Industrial Immune System, however, easily detects infections across the digital estate, regardless of the type of environment or technology. Darktrace AI does not rely on signature-based methods but instead continuously updates its understanding of what constitutes ‘normal’ in an industrial environment. This self-learning approach allows the AI to contain zero-days that have never been seen before in the wild, as well as detecting the new appearance of pre-existing attacks.

Industrial IoT attacked

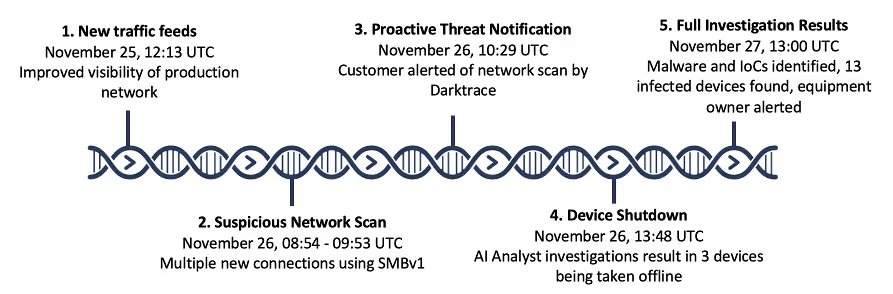

Only a few hours after Darktrace AI had begun defending the wider connections and interactions across the manufacturing firm, the Industrial Immune System detected a highly unusual network scan. A timeline of events, from first scan to full incident response results and conclusions, is shown below:

Darktrace’s AI recognized that the device was exploiting an SMBv1 protocol in order to attempt lateral movement. In addition to anonymous SMBv1 authentication, Darktrace detected the device abusing default vendor credentials for device enumeration.

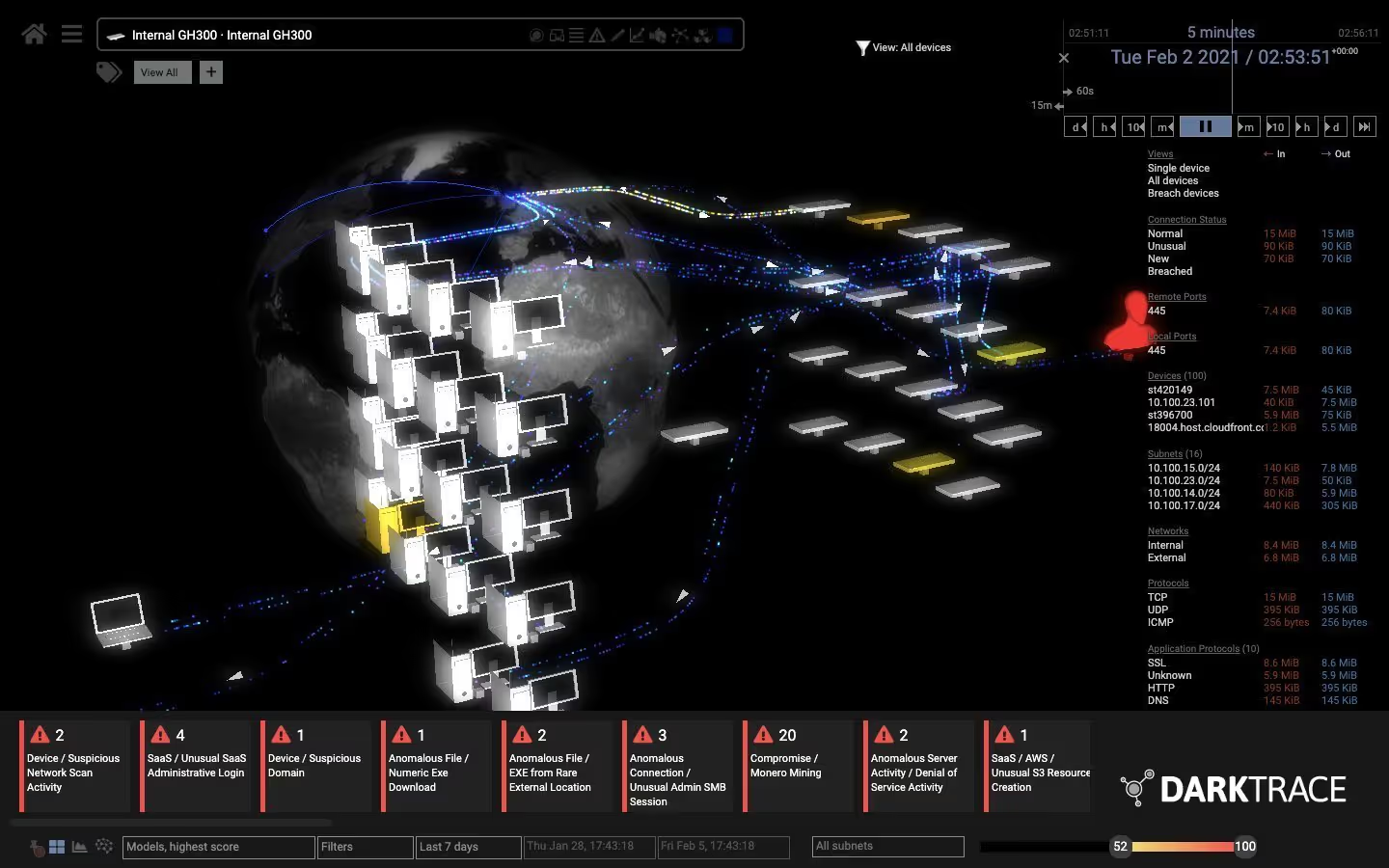

The device made a large number of unusual connections, including connections to internal endpoints which the company had previously been unaware of. As these occurred, the Threat Visualizer, Darktrace’s user interface, provided a graphical visualization of the incident, illuminating the unusual activity’s spread from the infected device across the infrastructure in question.

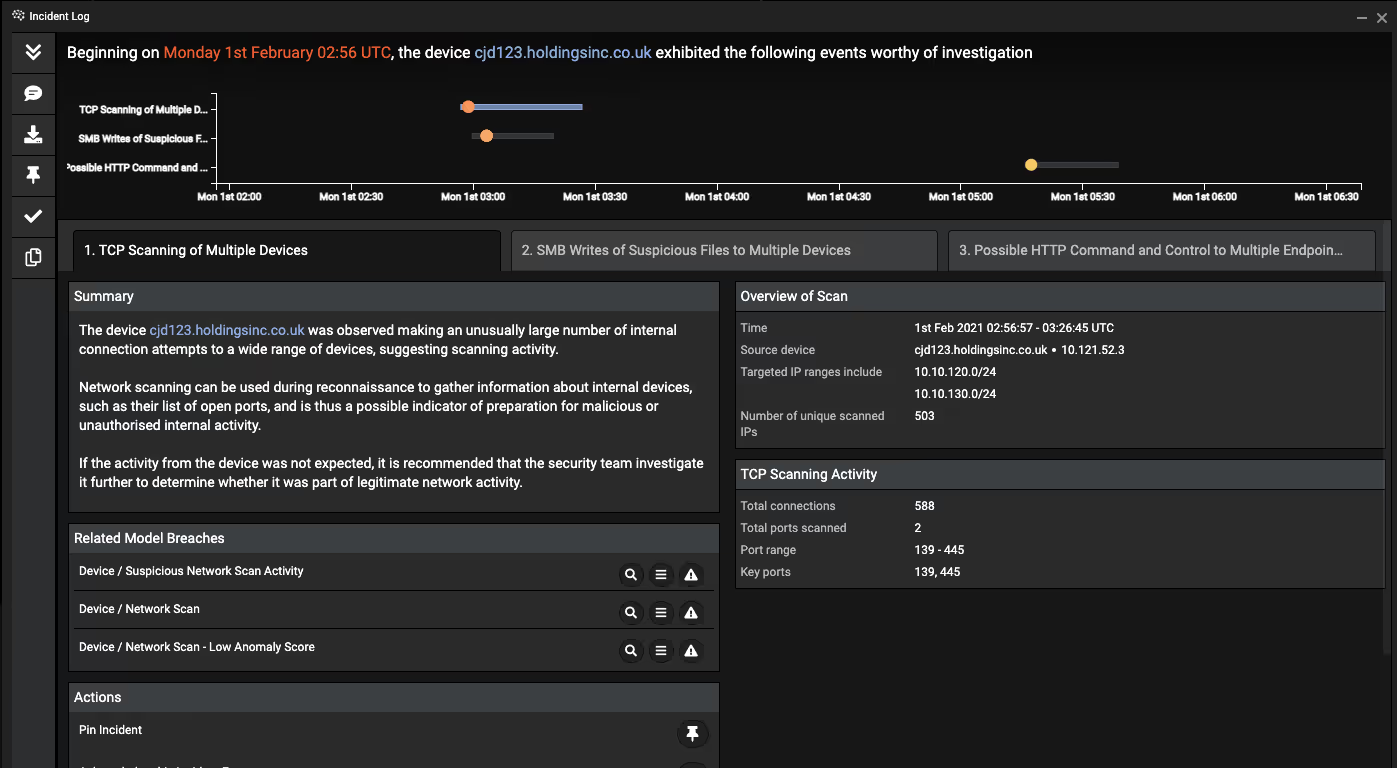

Darktrace’s Immune System identified that the infected Industrial IoT device was making an unusually large number of internal connections, suggesting an effort to perform reconnaissance.

Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst launched an immediate investigation into the alert, surfacing an incident summary at machine speed with all the information the security team needed to act.

The Cyber AI Analyst further identified two other devices behaving in a similar way, and these were removed from the network by the customer in response. When investigated by the security team, these devices were shown to be infected with the Yalove and Renocide worms, and the Autoit trojan-dropper. Open source intelligence suggests these infections are often spread via removable media such as USB drives.

Using Darktrace’s Advanced Search function, the customer was able to investigate related model breaches to build a list of similar indicators of compromise (IoCs), including failed external connections to www.whatismyip[.]com and DYNDNS IP addresses on HTTP port 80.

Recurring infections: How to deal with a persistent attack

In total, Darktrace was used to identify 13 infected production devices. The customer contacted the equipment owner, whose response confirmed that they had seen similar attacks on other networks in the past, including recurring infections.

Recurring infections imply one of two things: either, that the malware has a persistence mechanism, where it uses a range of techniques to remain undetected on the exploited machine and achieve persistent access to the system. Alternatively, a recurring infection could mean that the IoT manufacturer was not able to find all infected devices when they were first alerted to the compromise, and thus did not shut down the attack in its entirety.

As the infected machines are owned by a third party, they could not be immediately remediated. Darktrace AI, however, contained this threat with minimal business disruption. The customer was able to leave the infected devices active, which were still needed for production, confident that Darktrace would alert them if the infection spread or changed in behavior.

Industrial IoT: Shining a light on pre-existing threats

The mass adoption of Industrial IoT devices has made industrial environments more complex and more vulnerable than ever. This blog demonstrates the prevalent threat that attackers are already on the inside, and the importance for security teams to expand visibility over their full industrial system. In this case, the customer was able to use Darktrace’s AI to illuminate a previous blind spot and contain a persistent attack, while minimizing disruption to operations. Crucially, this ‘unknown known’ threat was detected without any prior knowledge of the devices, their supplier, or patch history, and without using malware signatures or IoCs.

The customer was made aware of the infection via the Darktrace SOC service. Yet the same outcome could have been obtained with other workflows provided by Darktrace, such as email alerting, notifications through the Darktrace mobile app, seamlessly integrating Darktrace with a SIEM solution, or alerting via an internal SOC.

Cyber AI Analyst enabled the customer to perform immediate incident response. While waiting for a reinstallation date with the equipment owner, the customer could keep the production devices online, knowing Darktrace would be monitoring the outstanding risk. In an industrial setting, trade-offs like this are often necessary to sustain production. Darktrace helps organizations maintain the vigilance they need to do this securely, and when remediation does become possible, Darktrace can be used to reliably locate the full extent of the infection.

Thanks to Darktrace analyst Oakley Cox for his insights on the above threat find.

Find out more about the Industrial Immune System

Darktrace model detections:

- Device / Suspicious Network Scan Activity [Enhanced Monitoring]

- Device / ICMP Address Scan

- ICS / Anomalous IT to ICS Connection

- Anomalous Connection / SMB Enumeration

- Device / Network Scan