In recent weeks, security researchers and cyber security vendors have noted an increase in malvertising campaigns on Google, aimed at infiltrating info-stealer malware into the systems of unsuspecting victims, as reported in sources [1] [2]. It has been observed that when individuals search for popular tools such as Notepad++, Zoom, AnyDesk, Foxit, Photoshop, and others on Google, they may encounter ads that redirect them to malicious sites. This report aims to provide a high-level analysis of one such campaign, specifically focusing on the delivery of the Vidar Info-stealer malware.

Campaign Details

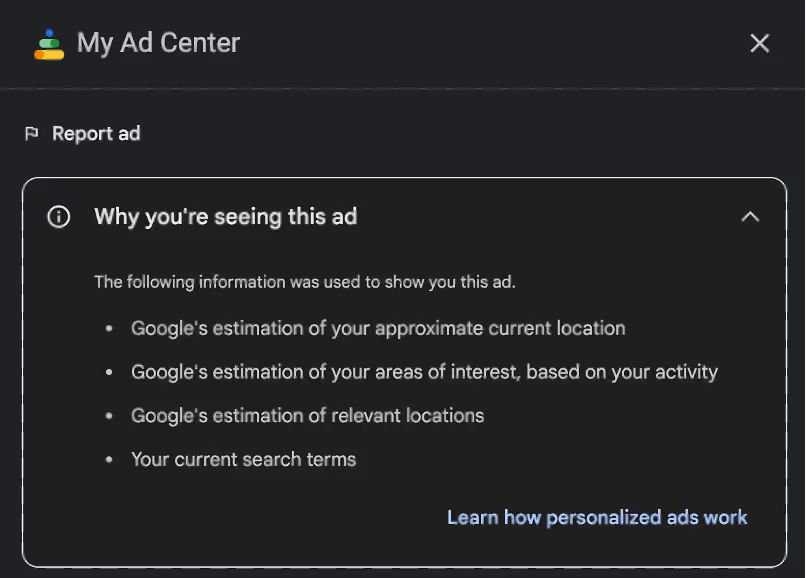

On the 25th of January 2023, Darktrace researchers observed that the advertisement depicted in Figure 1 was being displayed on Google when searching for the term "Notepad++" from within the United States.

As can be seen in Figure 2, the advertisement in question had no visible information regarding its publisher.

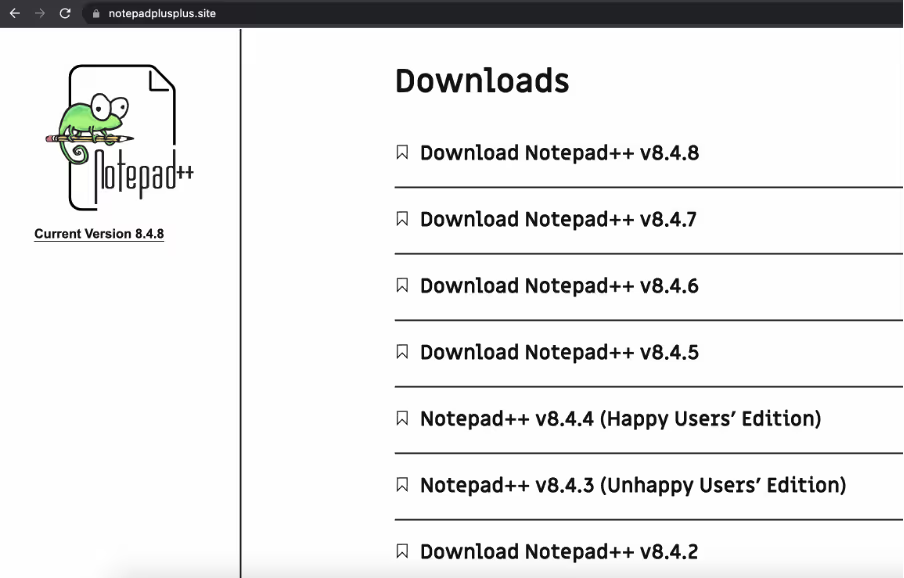

Clicking on the advertisement would direct potential victims to the website notepadplusplus.site, which had been registered on the 4th of January and is hosted on IP address 37[.]140[.]192[.]11. Upon selecting the desired version of the software, a download button is presented to the visitor.

When clicking on Download, regardless of the version selected, the traffic is then redirected to hxxps://download-notepad-plus-plus[.]duckdns[.]org/, and a .zip file with name “npp.Installer.x64.zip” is downloaded.

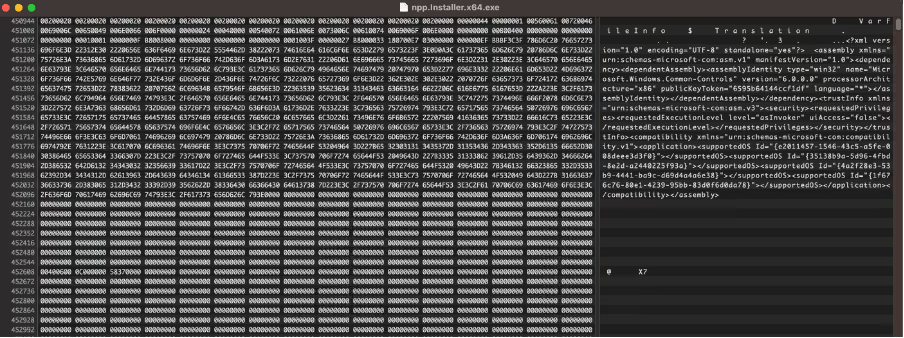

Upon extraction, the file "npp.Installer.x64.exe" has a file size of 684.1 megabytes. The significant size is attributed to the inclusion of an excessive number of null bytes, which serve to prevent the file from being scanned by some Antivirus and uploaded to malware analysis platforms such as VirusTotal, which has a file size limit of 650 megabytes.

Initially, padding was incorporated at the end of the executable, enabling individuals to remove it while maintaining a fully functional file. However, in the sample analysed in this report, padding was inserted into the binary's central region. This method renders the removal of padding more challenging, as simply deleting the zeroes would compromise the integrity of the file and impede its functionality during dynamic analysis.

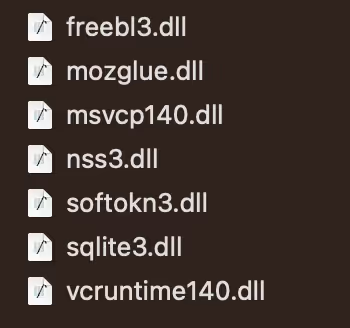

After execution, the malware promptly establishes a connection to a Telegram channel to acquire its command and control (C2) address, specifically hxxp://95[.]217[.]16[.]127. If Telegram is not available, the malware will then attempt to connect to a profile on video game platform Steam, in which case the C2 address was hxxp://157[.]90.148[.]112/ at the time of initial analysis and hxxp://116[.]203[.]6[.]107 later. It then proceeds to check-in and obtain its configuration file and subsequently downloads get.zip, an archive containing several legitimate DLL libraries, which are utilized to extract information and saved passwords from various applications and browsers. Through traffic analysis, the method by which the malware obtains its Command and Control (C2) location, and analysis of the configuration obtained, it can be assessed with high confidence that the malware in question is the info-stealer known as Vidar. Vidar has been extensively covered by various cybersecurity organizations. Further information regarding this info-stealer and its origins can be found here[3].

Campaign ID 827

The domain download-notepad-plus-plus.duckdns.org, from which the malware is distributed, resolves to the IP address 185[.]163[.]204[.]10. Using passive DNS, it has been determined that multiple domains also resolve to this IP address. This information suggests that the threat group responsible for this campaign is also utilizing advertising to target individuals searching for specific applications besides Notepad++, including:

- OBS Studio

- Davinci Resolve

- Sqlite

- Rufus

- Krita

Furthermore, it has been observed that all the malware samples obtained in this investigation connect to the same Telegram channel, utilize the same two Command and Control IP addresses, and share the same campaign ID of "827".

Conclusion

The recent proliferation of malvertising campaigns, which are employed by cyber-criminals to distribute malware, has become a significant cause for concern. Unlike more traditional infection vectors, such as email, malvertising is harder to protect against. Furthermore, the use of padding techniques to inflate the size of malware payloads can make detection and analysis more challenging.

To mitigate the risk of falling victim to such attacks, it is recommended to exercise caution when interacting with online advertisements. Specifically, it is advisable to avoid clicking on any advertisements while searching for free software on search engines and to instead download programs directly from official sources. This approach can reduce the likelihood of inadvertently downloading malware from untrusted sources.

Another effective measure to counteract the threat of malicious ads is the utilization of ad-blocker software. The implementation of an ad-blocker can provide an additional layer of protection against malvertising campaigns and enhance overall cybersecurity.

Appendices

Indicators of Compromise

Filename npp.Installer.x64.zip

SHA256 Hash 7DFD1D4FE925F802513FEA5556DE53706D9D8172BFA207D0F8AAB3CEF46424E8

Filename npp.Installer.x64.exe

SHA256 Hash 368008b450397c837f0b9c260093935c5cef56646e16a375ba7c47fea5562bfd

Filename rufus-3.21.zip

SHA256 Hash 75db4f8187abf49376a6ff3de0163b2d708d72948ea4b3d5645b86a0e41af084

Filename rufus-3.21.exe

SHA256 Hash 169603a5b5d23dc2f02dc0f88a73dcdd08a5c62d12203fb53a3f43998c04bb41

Filename DaVinci_Resolve_18.1.2_Windows.zip

SHA256 Hash 73f00e3b3ab01f4d5de42790f9ab12474114abe10cd5104f623aef9029c15b1e

Filename DaVinci_Resolve_18.1.2_Windows.exe

SHA256 Hash 169603a5b5d23dc2f02dc0f88a73dcdd08a5c62d12203fb53a3f43998c04bb41

Filename krita-x64-5.1.5-setup.zip

SHA256 Hash 85eb4b0e3922312d88ca046d89909fba078943aea3b469d82655a253e0d3ac67

Filename krita-x64-5.1.5-setup.exe

SHA256 Hash 169603a5b5d23dc2f02dc0f88a73dcdd08a5c62d12203fb53a3f43998c04bb41

URL hxxp://95[.]217[.]16[.]127/827 URL hxxp://95[.]217[.]16[.]127/get[.]zip URL hxxp://95[.]217[.]16[.]127/ URL hxxp://157[.]90[.]148[.]112/827 URL hxxp://157[.]90[.]148[.]112/ URL hxxp://157[.]90[.]148[.]112/get[.]zip URL hxxp://116[.]203[.]6[.]107/ Domain notepadplusplus[.]site Domain download-notepad-plus-plus[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-obsstudio[.]duckdns[.]org Domain dowbload-notepadd[.]duckdns[.]org Domain dowbload-notepad1[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-davinci-resolve[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-davinci[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-sqlite[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-davinci17[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-rufus[.]duckdns[.]org Domain download-kritapaint[.]duckdns[.]org IP Address 37[.]140[.]192[.]11 IP Address 185[.]163[.]204[.]10 IP Address 95[.]217[.]16[.]127 IP Address 157[.]90[.]148[.]112 IP Address 116[.]203[.]6[.]107 URL hxxps://t[.]me/litlebey URL hxxps://steamcommunity[.]com/profiles/76561199472399815

References

[1] https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/hackers-push-malware-via-google-search-ads-for-vlc-7-zip-ccleaner/

[2] https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/ransomware-access-brokers-use-google-ads-to-breach-your-network/

[3] https://www.team-cymru.com/post/darth-vidar-the-dark-side-of-evolving-threat-infrastructure

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)