Introduction

Good defence is like an onion, it has layers. Each part of a security implementation should have checks built in so that if one wall is breached, there are further contingencies. Security aficionados call this ‘defence in depth’, a military concept introduced to the cyber-sphere in 2009 [1]. Since then, it has remained a central tenet when designing secure systems, digital or otherwise [2]. Despite this, the attacker’s advantage is ever-present with continued development of malware and zero-day exploits. No matter how many layers a security platform has, how can organisations be expected to protect against a threat they do not know or even understand?

Take the case of one Darktrace customer, a government-contracted manufacturing company located in the Americas. This company possesses a modern OT and IT network comprised of several thousand devices. They have dozens of servers, a few of which host Microsoft Exchange. Every week, these few mail servers receive hundreds of malicious payloads which will ultimately attempt to make their way into over a thousand different inboxes while dodging different security gateways. Had the RESPOND portion of Darktrace for Email been properly enabled, this is where the story would have ended. However, in June 2022 an employee made an instinctual decision that could have potentially cost the company its time, money, and reputation as a government contractor. Their crime: opening an unknown html file attached to a compelling phishing email.

Following this misstep, a download was initiated which resulted in compromise of the system via vulnerable Microsoft admin tools from endpoints largely unknown to conventional OSINT sources. Using these tools, further malicious connectivity was accomplished before finally petering out. Fortunately, their existing Microsoft security gateway was up to date on the command and control (C2) domains observed in this breach and refused the connections.

Darktrace detected this activity at every turn, from the initial email to the download and subsequent attempted C2. Cyber AI Analyst stitched the events together for easy understanding and detected Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) that were not yet flagged in the greater intelligence community and, critically, did this all at machine speed.

So how did the attacker evade action for so long? The answer is product misconfiguration - they did not refine their ‘layers’.

Attack Details

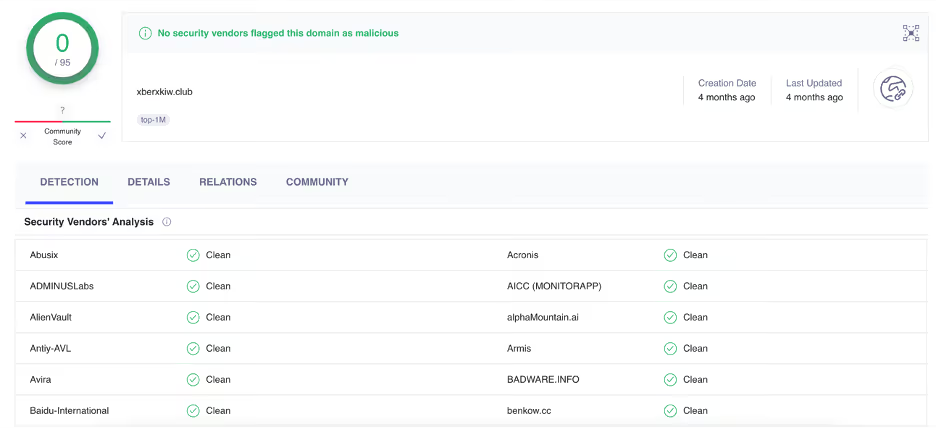

On the night of June 8th an employee received a malicious email. Darktrace detected that this email contained a html attachment which itself contained links to endpoints 100% rare to the network. This email also originated from a never-before-seen sender. Although it would usually have been withheld based on these factors, the customer’s Darktrace/Email deployment was set to Advisory Mode meaning it continued through to the inbox. Late the next day, this user opened the attachment which then routed them to the 100% rare endpoint ‘xberxkiw[.]club’, a probable landing page for malware that did not register on OSINT available at the time.

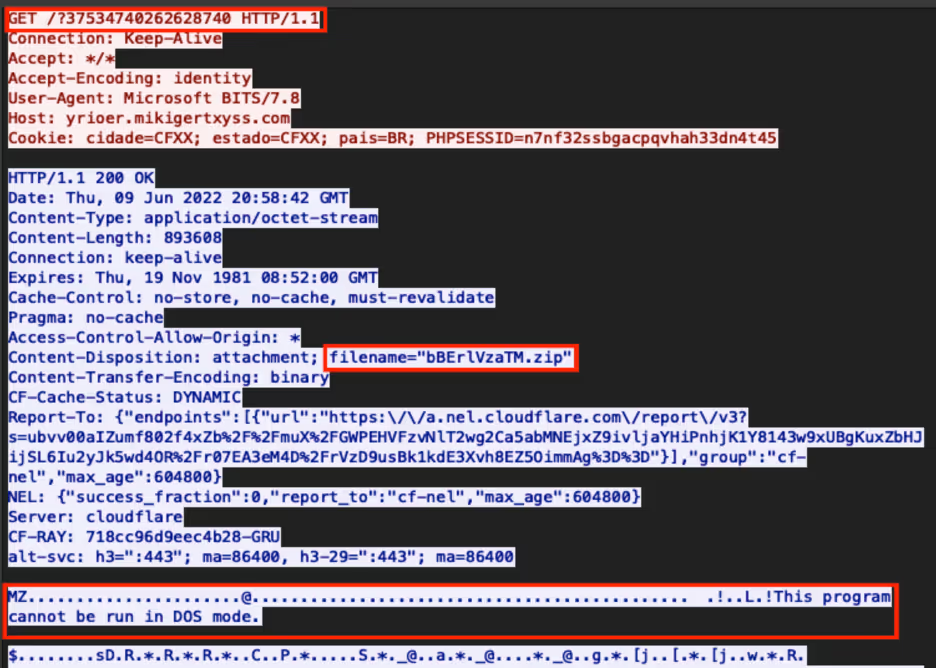

Only seconds after reaching the endpoint, Darktrace detected the Microsoft BITS user agent reaching out to another 100% rare endpoint ‘yrioer[.]mikigertxyss[.]com’, which generated a DETECT/Network model breach, ‘Unusual BITS Activity’. This was immediately suspicious since BITS is a deprecated and insecure windows admin tool which has been known to facilitate the movement of malicious payloads into and around a network. Upon successfully establishing a connection, the affected device began downloading a self-professed .zip file. However, Darktrace detected this file to be an extension-swapped .exe file. A PCAP of this activity can be seen below in Figure 2.

This activity also triggered a correlating breach of the ‘Masqueraded File Transfer’ model and pushed a high-fidelity alert to the Darktrace Proactive Threat Notification (PTN) service. This ensured both Darktrace and the customer’s SOC team were alerted to the anomalous activity.

At this stage the local SOC were likely beginning their triage. However further connections were being made to extend the compromise on the employee’s device and the network. The file they downloaded was later revealed to be ‘AutoIT3.exe’, a default filename given to any AutoIt script. AutoIt scripts do have legitimate use cases but are often associated with malicious activity for their ability to interact with the Windows GUI and bypass client protections. After opening, these scripts would launch on the host device and probe for other weaknesses. In this case, the script may have attempted to hunt passwords/default credentials, scan the local directory for common sensitive files, or scout local antivirus software on the device. It would then share any information gathered via established C2 channels.

After the successful download of this mismatched MIME type, the device began attempting to further establish C2 to the endpoint ‘dirirxhitoq[.]kialsoyert[.]tk’. Even though OSINT still did not flag this endpoint, Darktrace detected this outreach as suspicious and initiated its first Cyber AI Analyst investigation into the beaconing activity. Following the sixth connection made to this endpoint on the 10th of June, the infected device breached C2 models, such as ‘Agent Beacon (Long Period)’ and ‘HTTP Beaconing to Rare Destination’.

As the beaconing continued, it was clear that internal reconnaissance from AutoIt was not widely achieved, although similar IOCs could be detected on at least two other internal devices. This may represent other users opening the same malicious email, or successful lateral movement and infection propagation from the initial user/device. However comparatively, these devices did not experience the same level of infection as the first employee’s machine and never downloaded any malicious executables. AutoIt has a history of being used to deliver information stealers, which suggests a possible motivation had wider network compromise been successful [3].

Thankfully, after the 10th of June no further exploitation was observed. This was likely due to the combined awareness and action brought by the PTN alerting, static security gateways and action from the local security team. The company were protected thanks to defence in depth.

Darktrace Coverage

Despite this, the role of Darktrace itself cannot be understated. Darktrace/Email was integral to the early detection process and provided insight into the vector and delivery methods used by this attacker. Post-compromise, Darktrace/Network also observed the full range of suspicious activity brought about by this incursion. In particular, the AI analyst feature played a major role in reducing the time for the SOC team to triage by detecting and flagging key information regarding some of the earliest IOCs.

Alongside the early detection, there were several instances where RESPOND/Network would have intervened however autonomous actions were limited to a small test group and not enabled widely throughout the customer’s deployment. As such, this activity continued unimpeded- a weak layer. Figure 4 highlights the first Darktrace RESPOND action which would have been taken.

This Darktrace RESPOND action provides a precise and limited response by blocking the anomalous file download. However, after continued anomalous activity, RESPOND would have strengthened its posture and enforced stronger curbs across the wider anomalous activity. This stronger enforcement is a measure designed to relegate a device to its established norm. The breach which would generate this response can be seen below:

Although Darktrace RESPOND was not fully enabled, this company had an extra layer of security in the PTN service, which alerted them just minutes after the initial file download was detected, alongside details relevant to the investigation. This ensured both Darktrace analysts and their own could review the activity and begin to isolate and remediate the threat.

Concluding Insights

Thankfully, with multiple layers in their security, the customer managed to escape this incident largely unscathed. Quick and comprehensive email and network detection, customer alerting and local gateway blocking C2 connections ensured that the infection did not have leeway to propagate laterally throughout the network. However, even though this infection did not lead to catastrophe, the fact that it happened in the first place should be a learning point.

Had RESPOND/Email been properly configured, this threat would have been stopped before reaching its intended recipients, removing the need to rely on end-users as a security measure. Furthermore, had RESPOND/Network been utilized beyond a limited test group, this activity would have been blocked at every other step of the network-level kill chain. From the anomalous MIME download to the establishment of C2, Darktrace RESPOND would have been able to effectively isolate and quarantine this activity to the host device, without any reliance on slow-to-update OSINT sources. RESPOND allows for the automation of time-sensitive security decisions and adds a powerful layer of defence that conventional security solutions cannot provide. Although it can be difficult to relinquish human ownership of these decisions, doing so is necessary to prevent unknown attackers from infiltrating using unknown vectors to achieve unknown ends.

In conclusion, this incident demonstrates an effective case study around detecting a threat with novel IOCs. However, it is also a reminder that a company’s security makeup can always be improved. Overall, when building security layers in a company’s ‘onion’, it is great to have the best tools, but it is even greater to use them in the best way. Only with continued refining can organisations guarantee defence in depth.

Thanks to Connor Mooney and Stefan Rowe for their contributions.

Appendices

Darktrace Model Detections

· Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

· Compromise / Agent Beacon (Long Period)

· Compromise / HTTP Beaconing to Rare Destination

· Device / Large Number of Model Breaches

· Device / Suspicious Domain

· Device / Unusual BITS Activity

· Enhanced Monitoring: Anomalous File / Masqueraded File Transfer