Introduction

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, cyber communities around the world have been witnessing what can be called a ‘renaissance of cyberwarfare' [1]. Rather than being financially motivated, threat actors are being guided by political convictions to defend allies or attack their enemies. This blog reviews some of the main threat actors involved in this conflict and their ongoing tactics, and advises on how organizations can best protect themselves. Darktrace’s preliminary assessments predicted that attacks would be observed globally with a focus on pro-Ukrainian nations such as North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members and that identified Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups would develop new and complex malware deployed through increasingly sophisticated attack vectors. This blog will show that many of these assessments had unexpected outcomes.

Context for Conflict

Cyber confrontation between Russia and Ukraine dates back to 2013, when Viktor Yanukovych, (former President of Ukraine) rejected an EU trade pact in favour of an agreement with Russia. This sparked mass protests leading to his overthrow, and shortly after, Russian troops annexed Crimea and initiated the beginning of Russian-Ukrainian ground and cyber warfare. Since then, Russian threat actors have been periodically targeting Ukrainian infrastructure. One of the most notable examples of this, an attack against their national power grid in December 2015, resulted in power outages for approximately 255,000 people in Ukraine and was later attributed to the Russian hacking group Sandworm [2 & 3].

Another well-known attack in June 2017 overwhelmed the websites of hundreds of Ukrainian organizations using the infamous NotPetya malware. This attack is still considered the most damaging cyberattack in history, with more than €10 billion euros in financial damage [4]. In February 2022, countries witnessed the next stage of cyberwar against Ukraine with both new and familiar actors deploying various techniques to target their rival’s critical infrastructure.

Tactic 1: Ransomware

Although some sources suggest US ransomware incidents and expectations of ransom may have declined during the conflict, ransomware still remained a significant tactic deployed globally across this period [5] [6] [7]. A Ukrainian hacking group, Network Battalion 65 (NB65), used ransomware to attack the Russian state-owned television and radio broadcasting network VGTRK. NB65 managed to steal 900,000 emails and 4000 files, and later demanded a ransom which they promised to donate to the Ukrainian army. This attack was unique because the group used the previously leaked source code of Conti, another infamous hacker group that had pledged its support to the Russian government earlier in the conflict. NB65 modified the leaked code to make unique ransomware for each of its targets [5].

Against expectations, Darktrace’s customer base appeared to deviate from these ransom trends. Analysts have seen relatively unsophisticated ransomware attacks during the conflict period, with limited evidence to suggest they were connected to any APT activity. Between November 2021 and June 2022, there were 51 confirmed ransomware compromises across the Darktrace customer base. This represents an increase of 43.16% compared to the same period the year before, accounting for relative customer growth. Whilst this suggests an overall growth in ransom cases, many of these confirmed incidents were unattributed and did not appear to be targeting any particular verticals or regions. While there was an increase in the energy sector, this could not be explicitly linked to the conflict.

The Darktrace DETECT family has a variety of models related to ransomware visibility:

Darktrace Detections for T1486 (Data Encrypted for Impact):

- Compromise / Ransomware / Ransom or Offensive Words Written to SMB

- Compromise / Ransomware / Suspicious SMB Activity

- Anomalous Connection / Sustained MIME Type Conversion

- Unusual Activity / Sustained Anomalous SMB Activity

- Compromise / Ransomware / Suspicious SMB File Extension

- Unusual Activity / Anomalous SMB Read & Write

- Unusual Activity / Anomalous SMB Read & Write from New Device

- SaaS / Resource / SaaS Resources with Additional Extensions

- Compromise / Ransomware / Possible Ransom Note Read

- [If RESPOND is enabled] Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Ransomware Block

Tactic 2: Wipers

One of the largest groups of executables seen during the conflict were wipers. On the eve of the invasion, Ukrainian organizations were targeted by a new wiper malware given the name “HermeticWiper”. Hermetic refers to the name of the Cyprian company “Hermetica Digital Ltd.” which was used by attackers to request a code signing certificate [6]. Such a digital certificate is used to verify the ownership of the code and that it has not been altered. The 24-year-old owner of Hermetica Digital says he had no idea that his company was abused to retrieve a code signing certificate [7].

HermeticWiper consists of three components: a worm, decoy ransomware and the wiper malware. The custom worm designed for HermeticWiper was used to spread the malware across the network of its infected machines. ESET researchers discovered that the decoy ransomware and the wiper were released at the same time [8]. The decoy ransomware was used to make it look like the machine was hit by ransomware, when in reality the wiper was already permanently wiping data from the machines. In the attack’s initial stage, it bypasses Windows security features designed to prevent overwriting boot records by installing a separate driver. After wiping data from the machine, HermeticWiper prevents that data from being re-fragmented and overwrites the files to fragment it further. This is done to make it more challenging to reconstruct data for post-compromise forensics [9]. Overall, the function and purpose of HermeticWiper seems similar to that of NotPetya ransomware.

HermeticWiper is not the only conflict-associated wiper malware which has been observed. In January 2022, Microsoft warned Ukrainian customers that they detected wiper intrusion activity against several European organizations. One example of this was the MBR (Master Boot Record) wiper. This type of wiper overwrites the MBR, the disk sector that instructs a computer on how to load its operating system, with a ransomware note. In reality, the note is a misdirection and the malware destroys the MBR and targeted files [10].

One of the most notable groups that used wiper malware was Sandworm. Sandworm is an APT attributed to Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency, GRU. The group has been active since 2009 and has used a variety of TTPs within their attacks. They have a history of targeting Ukraine including attacks in 2015 on Ukraine’s energy distribution companies and in 2017 when they used the aforementioned NotPetya malware against several Ukrainian organizations [11]. Another Russian (or pro-Russian) group using wiper malware to target Ukraine is DEV-0586. This group targeted various Ukrainian organizations in January 2022 with Whispergate wiper malware. This type of wiper malware presents itself as ransomware by displaying a file instructing the victim to pay Bitcoin to have their files decrypted [12].

Darktrace did not observe any confirmed cases of HermeticWiper nor other conflict-associated wipers (e.g IsaacWiper and CaddyWiper) within the customer base over this period. Despite this, Darktrace DETECT has a variety of models related to wipers and data destruction:

Darktrace Detections for T1485 (Data Destruction)- this is the main technique exploited during wiper attacks

- Unusual Activity / Anomalous SMB Delete Volume

- IaaS / Unusual Activity / Anomalous AWS Resources Deleted

- IaaS / Storage / S3 Bucket Delete

- SaaS / Resource / Mass Email Deletes from Rare Location

- SaaS / Resource / Anomalous SaaS Resources Deleted

- SaaS / Resource / Resource Permanent Delete

- [If RESPOND is enabled] Antigena / Network / Manual / Enforce Pattern of Life

- [If RESPOND is enabled] Antigena / SaaS / Antigena Unusual Activity Block

Tactic 3: Spear-Phishing

Another strategy that some threat actors employ is spear-phishing. Targeting can be done using email, social media, messaging, or other platforms.

The hacking group Armageddon (also known as Gamaredon) has been responsible for several spear-phishing attacks during the crisis, primarily targeting individuals involved in the Ukrainian Government [13]. Since the beginning of the war, the group has been sending out a large volume of emails containing an HTML file which, if opened, downloads and launches a RAR payload. Those who click the attached link download an HTA with a PowerShell script which obtains the final Armageddon payload. Using the same strategy, the group is also targeting governmental agencies in the European Union [14]. With high-value targets, the need to improve teaching around phishing identification to minimize the chance of being caught in an attacker's net is higher than ever.

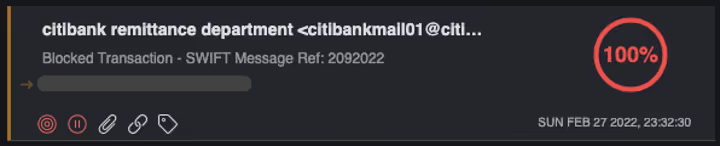

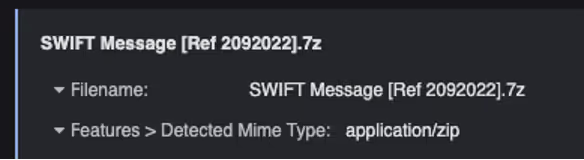

In comparison to the wider trends, Darktrace analysts again saw little-to-no evidence of conflict-associated phishing campaigns affecting customers. Those phishing attempts which did target customers were largely not conflict-related. In some cases, the conflict was used opportunistically, such as when one customer was targeted with a phishing email referencing Russian bank exclusions from the SWIFT payment system (Figures 1 and 2). The email was identified by Darktrace/Email as a probable attempt at financial extortion and inducement - in this case the company received a spoofed email from a major bank’s remittance department.

Although the conflict was used as a reference in some examples, in most of Darktrace’s observed phishing cases during the conflict period there was little-to-no evidence to suggest that the company being targeted nor the threat actor behind the phishing attempt was associated with or attributable to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

However, Darktrace/Email has several model categories which pick up phishing related threats:

Sample of Darktrace for Email Detections for T1566 (Phishing)- this is the overarching technique exploited during spear-phishing events

Model Categories:

- Inducement

- Internal / External User Spoofing

- Internal / External Domain Spoofing

- Fake Support

- Link to Rare Domains

- Link to File Storage

- Redirect Links

- Anomalous / Malicious Attachments

- Compromised Known Sender

Specific models can be located on the Email Console

Tactic 4: Distributed-Denial-of-Service (DDoS)

Another tactic employed by both pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian threat actors was DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks. Both pro-Russia and pro-Ukraine actors were seen targeting critical infrastructure, information resources, and governmental platforms with mass DDoS attacks. The Ukrainian Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, called on an IT Army of underground Ukrainian hackers and volunteers to protect Ukraine's critical infrastructure and conduct DDoS attacks against Russia [16]. As of 1 August 2022, more than two hundred thousand people are subscribed to the group's official Telegram channel, where potential DDoS targets are announced [17].

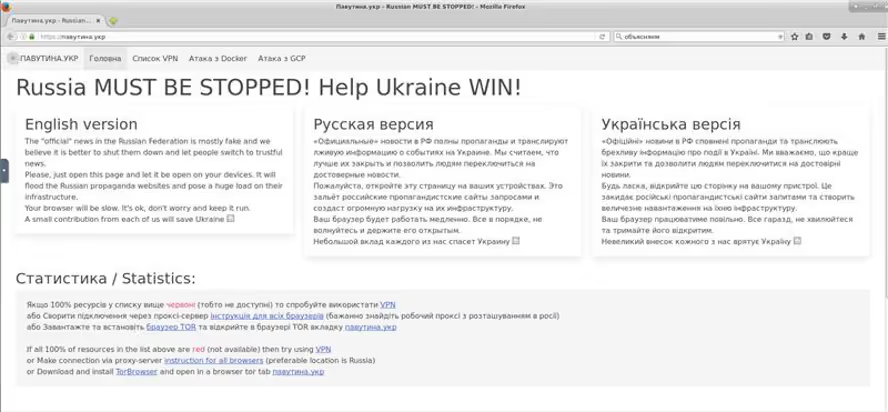

Darktrace observed similar pro-Ukraine DDoS behaviors within a variety of customer environments. These DDoS campaigns appeared to involve low-volume individual support combined with crowd-sourced DDoS activity. They were hosted on a range of public-sourced DDoS sites and seemed to share sentiments of groups such as the IT Army of Ukraine (Figure 3).

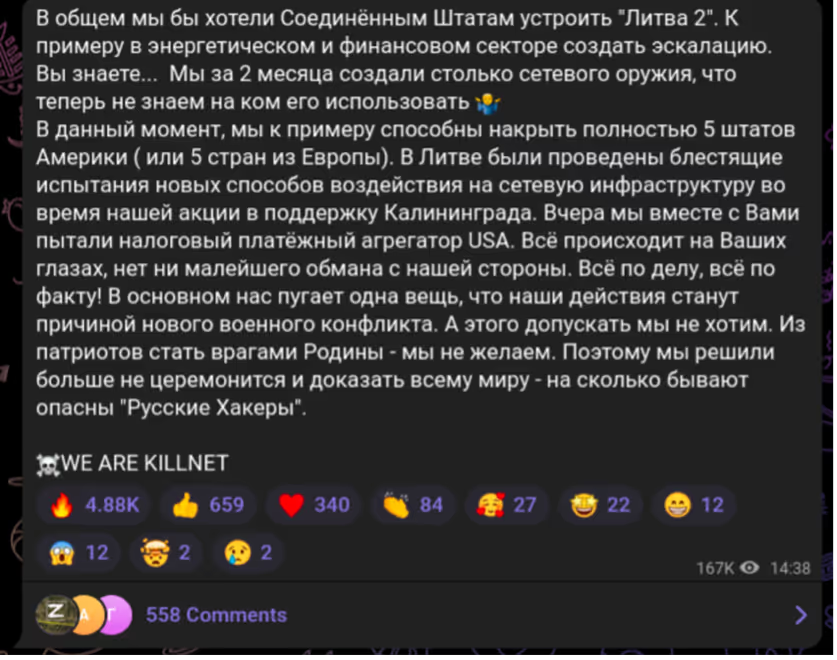

From the Russian side, one of the prominent newly emerged groups, Killnet, is striking back, launching several massive DDoS attacks against the critical infrastructure of countries that provide weaponry to Ukraine [18 & 19]. Today, the number of supporters of Killnet has grown to eighty-four thousand on their Telegram channel. The group has already launched a number of mass attacks on several NATO states, including Germany, Poland, Italy, Lithuania and Norway. This shows the conflict has attracted new and fast-growing groups with large backing and the capacity to undertake widespread attacks.

DETECT has several models to identify anomalous DoS/DDoS activity:

Darktrace Detection for T1498 (Network Denial of Service)- this is the main technique exploited during DDoS attacks

- Device / Anomaly Indicators / Denial of Service Activity Indicator

- Anomalous Server Activity / Possible Denial of Service Activity

- [If RESPOND is enabled] Antigena / Network / External Threat / Antigena Suspicious Activity Block

What did Darktrace observe?

Darktrace’s cross-fleet detections were largely contrary to expectations. Analysts did not see large-scale complex conflict-linked attacks utilizing either conflict-associated ransomware, malware, or other TTPs. Instead, cyber incidents observed were largely opportunistic, using malware that could be purchased through Malware-as-a-Service models and other widely available toolkits, (rather than APT or conflict-attributable attacks). Overall, this is not to say there have been no repercussions from the conflict or that opportunistic attacks will cease, but evidence suggests that there were fewer wider cyber consequences beyond the initial APT-based attacks seen in the public forum.

Another trend expected since the beginning of the conflict was targeted responses to sanction announcements focusing on NATO businesses and governments. Analysts, however, saw the limited reactive actions, with little-to-no direct impact from sanction announcements. Although cyber-attacks on some NATO organizations did take place, they were not as widespread or impactful as expected. Lastly, it was thought that exposure to new and sophisticated exploits would increase and be used to weaken NATO nations - especially corporations in critical industries. However, analysts observed relatively common exploits deployed indiscriminately and opportunistically. Overall, with the wider industry expecting chaos, Darktrace analysts did not see the crisis taken advantage of to target wider businesses outside of Ukraine. Based on this comparison between expectations and reality, the conflict has demonstrated the danger of falling prey to confirmation bias and the need to remain vigilant and expect the unexpected. It may be possible to say that cyberwar is ‘cold’ right now, however the element of surprise is always present, and it is better to be prepared to protect yourself and your organization.

What to Expect from the Future

As cyberattacks continue to become less monetarily and physically costly, it is to be expected that they will increase in frequency. Even after a political ceasefire is established, hacking groups can harbour resentment and continue their attacks, though possibly on a smaller scale.

Additionally, the longer this conflict continues, the more sophisticated hacking groups’s attacks may become. In one of their publications, Killnet shared with subscribers that they had created ‘network weaponry’ powerful enough to simultaneously take down five European countries (Figure 4) [20]. Whether or not this claim is true, it is vital to be prepared. The European Union and the United States have supported Ukraine since the start of the invasion, and the EU has also stated that it is considering providing further assistance to help Ukraine in cyberspace [21].

How to Protect Against these Attacks

In the face of wider conflict and cybersecurity tensions, it is crucial that organizations evaluate their security stack and practise the following:

· Know what your critical assets are and what software is running on them.

· Keep your software up to date. Prioritize patching critical and high vulnerabilities that allow remote code execution.

· Enforce Multifactor Authentication (MFA) to the greatest extent possible.

· Require the use of a password manager to generate strong and unique passwords for each separate account.

· Backup all the essential files on the cloud and external drives and regularly maintain them.

· Train your employees to recognize phishing emails, suspicious websites, infected links or other abnormalities to prevent successful compromise of email accounts.

In order to prevent an organization from suffering damage due to one of the attacks mentioned above, a full-circle approach is needed. This defence starts with a thorough understanding of the attack surface to provide timely mitigation. This can be supported by Darktrace products:

· As shown throughout this blog, Darktrace DETECT and Darktrace/Email have several models relating to conflict-associated TTPs and attacks. These help to quickly alert security teams and provide visibility of anomalous behaviors.

· Darktrace PREVENT/ASM helps to identify vulnerable external-facing assets. By patching and securing these devices, the risk of exploit is drastically reduced.

· Darktrace RESPOND and RESPOND/Email can make targeted actions to a range of threats such as blocking incoming DDoS connections or locking malicious email links.

Thanks to the Darktrace Threat Intelligence Unit for their contributions to this blog.

Appendices

Reference List

[2] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-cybersecurity-idUSKCN0VY30K

[3] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-cybersecurity-sandworm-idUSKBN0UM00N20160108

[4 & 11] https://www.wired.com/story/notpetya-cyberattack-ukraine-russia-code-crashed-the-world/

[6] https://ransomware.org/blog/has-the-ukraine-conflict-disrupted-ransomware-attacks/

[10] https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-cyber-cyprus-idCAKBN2KT2QI

[15] https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/aa22-057a

[16] https://attack.mitre.org/groups/G0047/

[17] https://cyware.com/news/ukraine-cert-warns-of-increasing-attacks-by-armageddon-group-850081f8

[18] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-60521822

[19] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/11/russia-cyberwarfare-us-ukraine-volunteer-hackers-it-army/

[20] https://t.me/itarmyofukraine2022

[19 & 20] https://flashpoint.io/blog/killnet-kaliningrad-and-lithuanias-transport-standoff-with-russia/

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)