In recent years, the prevalence of crypto-jacking botnets has risen in tandem with the popularity and value of cryptocurrencies. Increasingly crypto-mining malware programs are distributed by botnets as they allow threat actors to harness the cumulative processing power of a large number of machines (discussed in our other Darktrace blogs.1 2 One of these botnets is Sysrv-hello, which in addition to crypto-mining, propagates aggressively across the Internet in a worm-like manner by trolling for Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerabilities and SSH worming from the compromised victim devices. This all has the purpose of expanding the botnet.

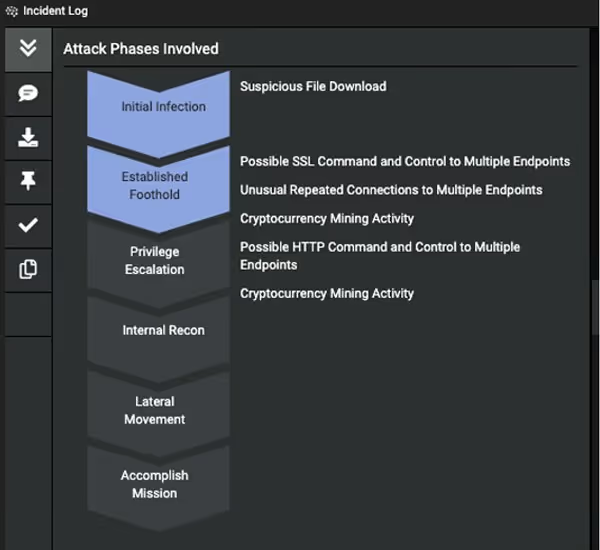

First identified in December 2020, Sysrv-hello’s operators constantly update and change the bots’ behavior to evolve and stay ahead of security researchers and law enforcement. As such, infected systems can easily go unnoticed by both users and organizations. This blog examines the cyber kill chain sequence of a Sysrv-hello botnet infection detected at the network level by Darktrace DETECT/Network, as well as the botnet’s tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) in March and April 2022.

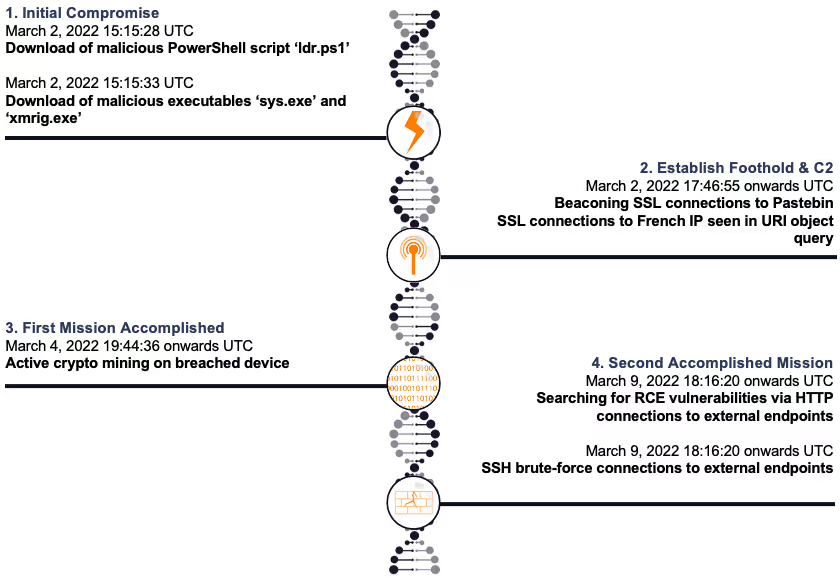

Figure 1: Timeline of the attack

Delivery and exploitation

The organization, which was trialing Darktrace, had deployed the technology on March 2, 2022. On the very same day, the initial host infection was seen through the download of a first-stage PowerShell loader script from a rare external endpoint by a device in the internal network. Although initial exploitation of the device happened prior to the installation and was not observed, this botnet is known to target RCE vulnerabilities in various applications such as MySQL, Tomcat, PHPUnit, Apache Solar, Confluence, Laravel, JBoss, Jira, Sonatype, Oracle WebLogic and Apache Struts to gain initial access to internal systems.3 Recent iterations have also been reported to have been deployed via drive-by-downloads from an empty HTML iframe pointing to a malicious executable that downloads to the device from a user visiting a compromised website.4

Initial intrusion

The Sysrv-hello botnet is distributed for both Linux and Windows environments, with the corresponding compatible script pulled based on the architecture of the system. In this incident, the Windows version was observed.

On March 2, 2022 at 15:15:28 UTC, the device made a successful HTTP GET request to a malicious IP address5 that had a rarity score of 100% in the network. It subsequently downloaded a malicious PowerShell script named ‘ldr.ps1'6 onto the system. The associated IP address ‘194.145.227[.]21’ belongs to ‘ASN AS48693 Rices Privately owned enterprise’ and had been identified as a Sysrv-hello botnet command and control (C2) server in April the previous year. 3

Looking at the URI ‘/ldr.ps1?b0f895_admin:admin_81.255.222.82:8443_https’, it appears some form of query was being executed onto the object. The question mark ‘?’ in this URI is used to delimit the boundary between the URI of the queryable object and the set of strings used to express a query onto that object. Conventionally, we see the set of strings contains a list of key/value pairs with equal signs ‘=’, which are separated by the ampersand symbol ‘&’ between each of those parameters (e.g. www.youtube[.]com/watch?v=RdcCjDS0s6s&ab_channel=SANSCyberDefense), though the exact structure of the query string is not standardized and different servers may parse it differently. Instead, this case saw a set of strings with the hexadecimal color code #b0f895 (a light shade of green), admin username and password login credentials, and the IP address ‘81.255.222[.]82’ being applied during the object query (via HTTPS protocol on port 8443). In recent months this French IP has also had reports of abuse from the OSINT community.7

On March 2, 2022 at 15:15:33 UTC, the PowerShell loader script further downloaded second-stage executables named ‘sys.exe’ and ‘xmrig.2 sver.8 9 These have been identified as the worm and cryptocurrency miner payloads respectively.

Establish foothold

On March 2, 2022 at 17:46:55 UTC, after the downloads of the worm and cryptocurrency miner payloads, the device initiated multiple SSL connections in a regular, automated manner to Pastebin – a text storage website. This technique was used as a vector to download/upload data and drop further malicious scripts onto the host. OSINT sources suggest the JA3 client SSL fingerprint (05af1f5ca1b87cc9cc9b25185115607d) is associated with PowerShell usage, corroborating with the observation that further tooling was initiated by the PowerShell script ‘ldr.ps1’.

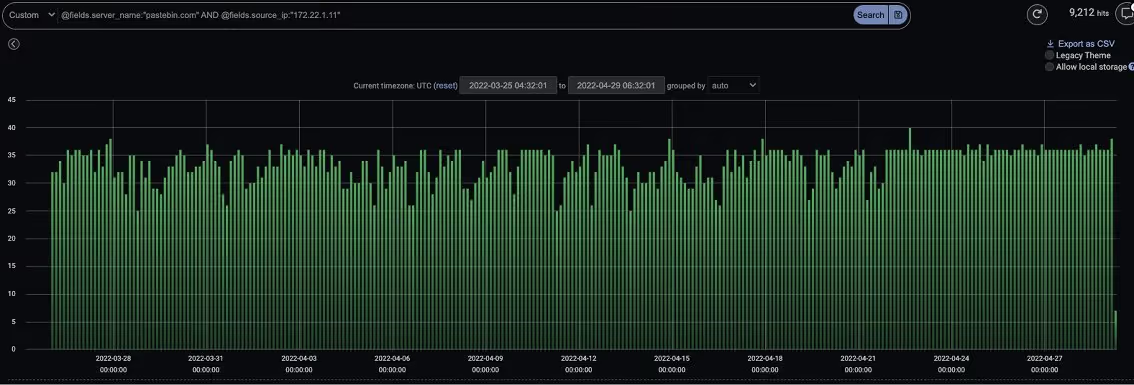

Continual Pastebin C2 connections were still being made by the device almost two months since the initiation of such connections. These Pastebin C2 connections point to new tactics and techniques employed by Sysrv-hello — reports earlier than May do not appear to mention any usage of the file storage site. These new TTPs serve two purposes: defense evasion using a web service/protocol and persistence. Persistence was likely achieved through scheduling daemons downloaded from this web service and shellcode executions at set intervals to kill off other malware processes, as similarly seen in other botnets.10 Recent reports have seen other malware programs also switch to Pastebin C2 tunnels to deliver subsequent payloads, scrapping the need for traditional C2 servers and evading detection.11

Figure 2: A section of the constant SSL connections that the device was still making to ‘pastebin[.]com’ even in the month of April, which resembles beaconing scheduled activity

Throughout the months of March and April, suspicious SSL connections were made from a second potentially compromised device in the internal network to the infected breach device. The suspicious French IP address ‘81.255.222[.]82’ previously seen in the URI object query was revealed as the value of the Server Name Indicator (SNI) in these SSL connections where, typically, a hostname or domain name is indicated.

After an initial compromise, attackers usually aim to gain long-term remote shell access to continue the attack. As the breach device does not have a public IP address and is most certainly behind a firewall, for it to be directly accessible from the Internet a reverse shell would need to be established. Outgoing connections often succeed because firewalls generally filter only incoming traffic. Darktrace observed the device making continuous outgoing connections to an external host listening on an unusual port, 8443, indicating the presence of a reverse shell for pivoting and remote administration.

Figure 3: SSL connections to server name ‘81.255.222[.]8’ at end of March and start of April

Accomplish mission

On March 4, 2022 at 15:07:04 UTC, the device made a total of 16,029 failed connections to a large volume of external endpoints on the same port (8080). This behavior is consistent with address scanning. From the country codes, it appears that public IP addresses for various countries around the world were contacted (at least 99 unique addresses), with the US being the most targeted.

From 19:44:36 UTC onwards, the device performed cryptocurrency mining using the Minergate mining pool protocol to generate profits for the attacker. A login credential called ‘x’ was observed in the Minergate connections to ‘194.145.227[.]21’ via port 5443. JSON-RPC methods of ‘login’ and ‘submit’ were seen from the connection originator (the infected breach device) and ‘job’ was seen from the connection responder (the C2 server). A high volume of connections using the JSON-RPC application protocol to ‘pool-fr.supportxmr[.]com’ were also made on port 80.

When the botnet was first discovered in December 2020, mining pools MineXMR and F2Pool were used. In February 2021, MineXMR was removed and in March 2021, Nanopool mining pool was added,12 before switching to the present SupportXMR and Minergate mining pools. Threat actors utilize such proxy pools to help hide the actual crypto wallet address where the contributions are made by the crypto-mining activity. From April onwards, the device appears to download the ‘xmrig.exe’ executable from a rare IP address ‘61.103.177[.]229’ in Korea every few days – likely in an attempt to establish persistency and ensure the cryptocurrency mining payload continues to exist on the compromised system for continued mining.

On March 9, 2022 from 18:16:20 UTC onwards, trolling for various RCE vulnerabilities (including but not limited to these four) was observed over HTTP connections to public IP addresses:

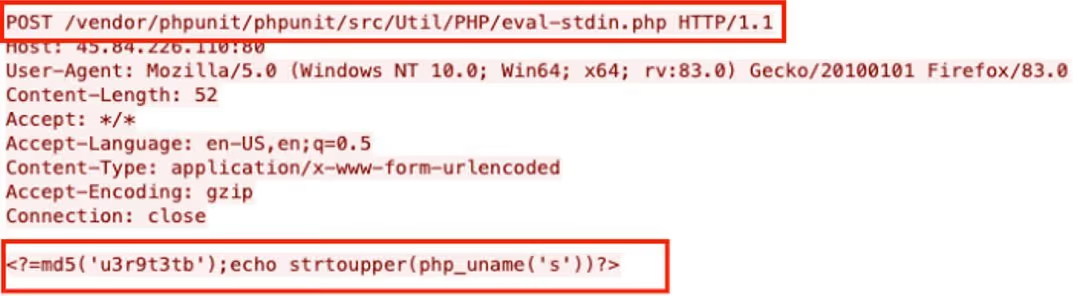

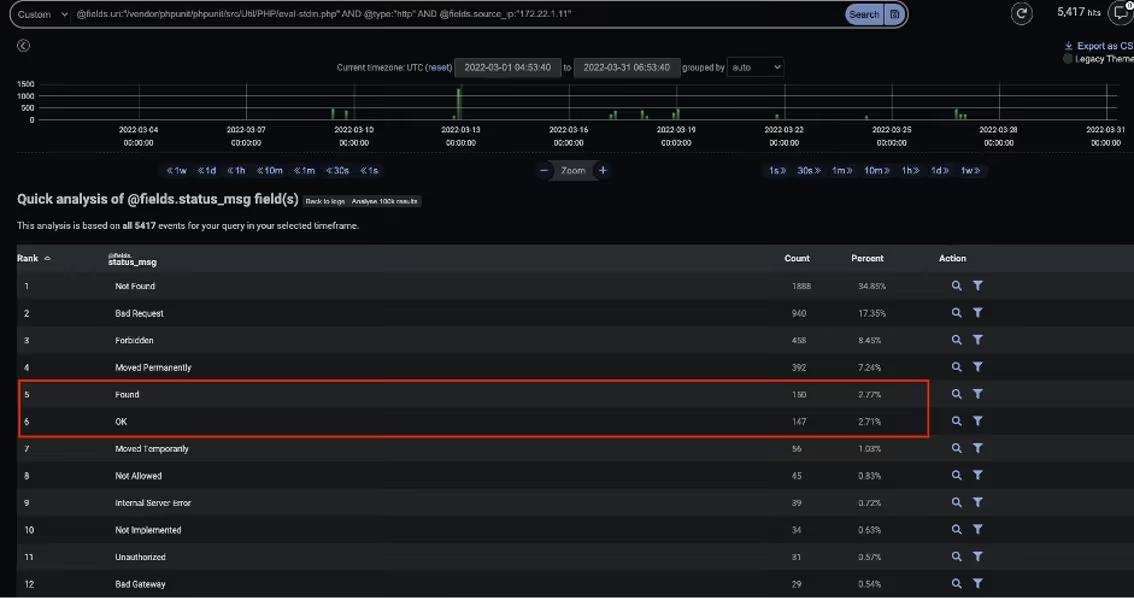

- Through March, the device made around 5,417 HTTP POSTs with the URI ‘/vendor/phpunit/phpunit/src/Util/PHP/eval-stdin.php’ to at least 99 unique public IPs. This appears to be related to CVE-2017-9841, which in PHPUnit allows remote attackers to execute arbitrary PHP code via HTTP POST data beginning with a ‘13 PHPUnit is a common testing framework for PHP, used for performing unit tests during application development. It is used by a variety of popular Content Management Systems (CMS) such as WordPress, Drupal and Prestashop. This CVE has been called “one of the most exploitable CVEs of 2019,” with around seven million attack attempts being observed that year.14 This framework is not designed to be exposed on the critical paths serving web pages and should not be reachable by external HTTP requests. Looking at the status messages of the HTTP POSTs in this incident, some ‘Found’ and ‘OK’ messages were seen, suggesting the vulnerable path could be accessible on some of those endpoints.

Figure 4: PCAP of CVE-2017-9841 vulnerability trolling

Figure 5: The CVE-2017-9841 vulnerable path appears to be reachable on some endpoints

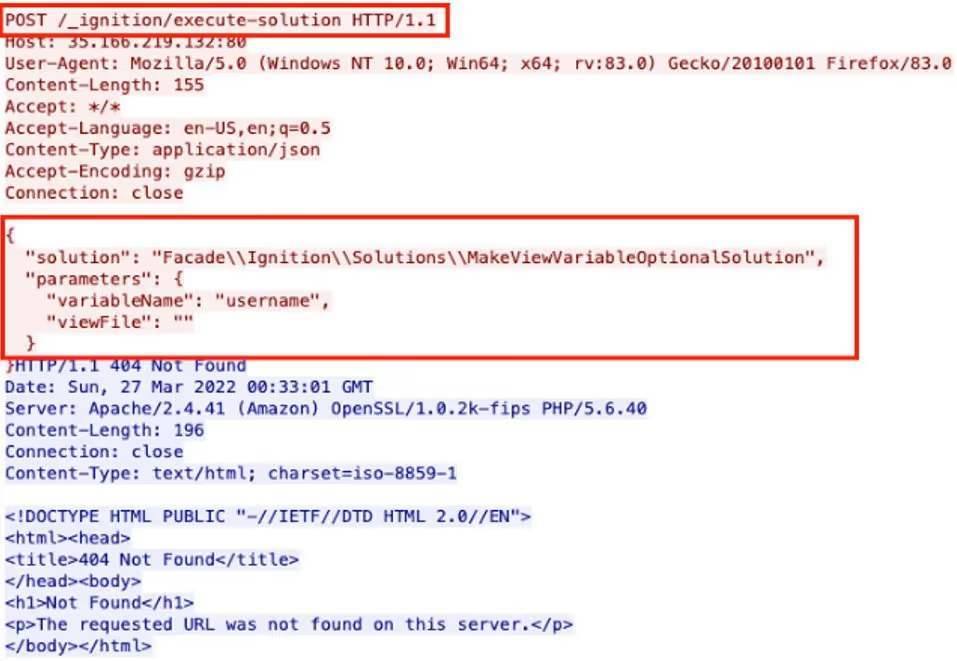

- Through March, the device also made around 5,500 HTTP POSTs with the URI ‘/_ignition/execute-solution’ to at least 99 unique public IPs. This appears related to CVE-2021-3129, which allows unauthenticated remote attackers to execute arbitrary code using debug mode with Laravel, a PHP web application framework in versions prior to 8.4.2.15 The POST request below makes the variable ‘username’ optional, and the ‘viewFile’ parameter is empty, as a test to see if the endpoint is vulnerable.16

Figure 6: PCAP of CVE-2021-3129 vulnerability trolling

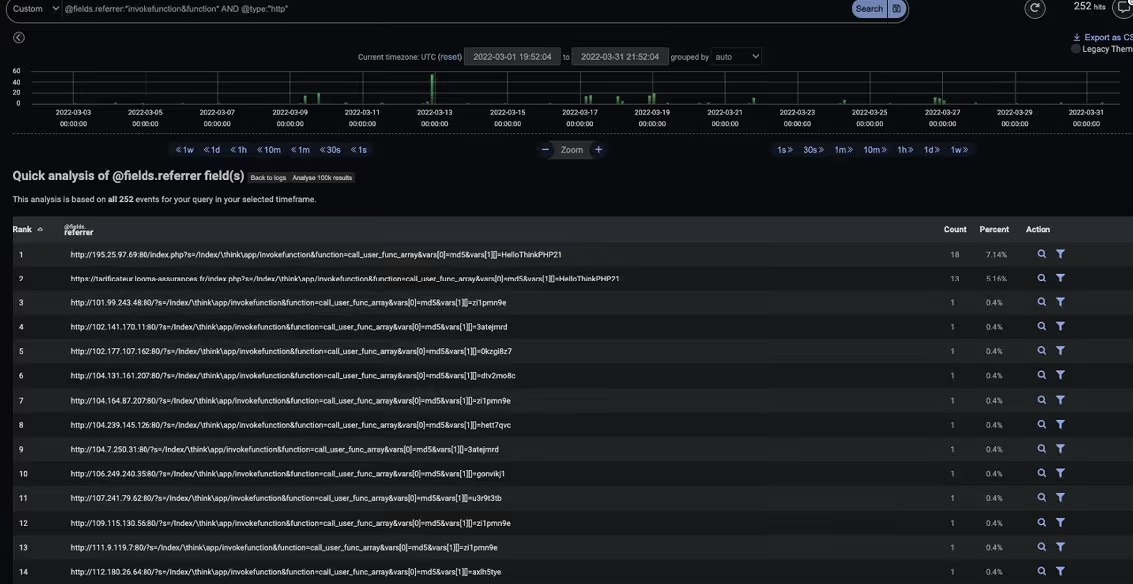

- The device made approximately a further 252 HTTP GETs with URIs containing ‘invokefunction&function’ to another minimum of 99 unique public IPs. This appears related to a RCE vulnerability in ThinkPHP, an open-source web framework.17

Figure 7: Some of the URIs associated with ThinkPHP RCE vulnerability

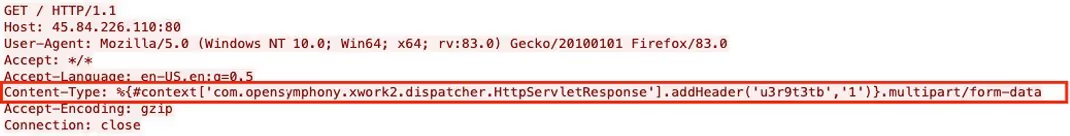

- A HTTP header related to a RCE vulnerability for the Jakarta Multipart parser used by Apache struts2 in CVE-2017-563818 was also seen during the connection attempts. In this case the payload used a custom Content-Type header.

Figure 8: PCAP of CVE-2017-5638 vulnerability trolling

Two widely used methods of SSH authentication are public key authentication and password authentication. After gaining a foothold in the network, previous reports3 19 have mentioned that Sysrv-hello harvests private SSH keys from the compromised device, along with identifying known devices. Being a known device means the system can communicate with the other system without any further authentication checks after the initial key exchange. This technique was likely performed in conjunction with password brute-force attacks against the known devices. Starting from March 9, 2022 at 20:31:25 UTC, Darktrace observed the device making a large number of SSH connections and login failures to public IP ranges. For example, between 00:05:41 UTC on March 26 and 05:00:02 UTC on April 14, around 83,389 SSH connection attempts were made to 31 unique public IPs.

Figure 9: Darktrace’s Threat Visualizer shows large spikes in SSH connections by the breach device

Figure 10: Beaconing SSH connections to a single external endpoint, indicating a potential brute-force attack

Darktrace coverage

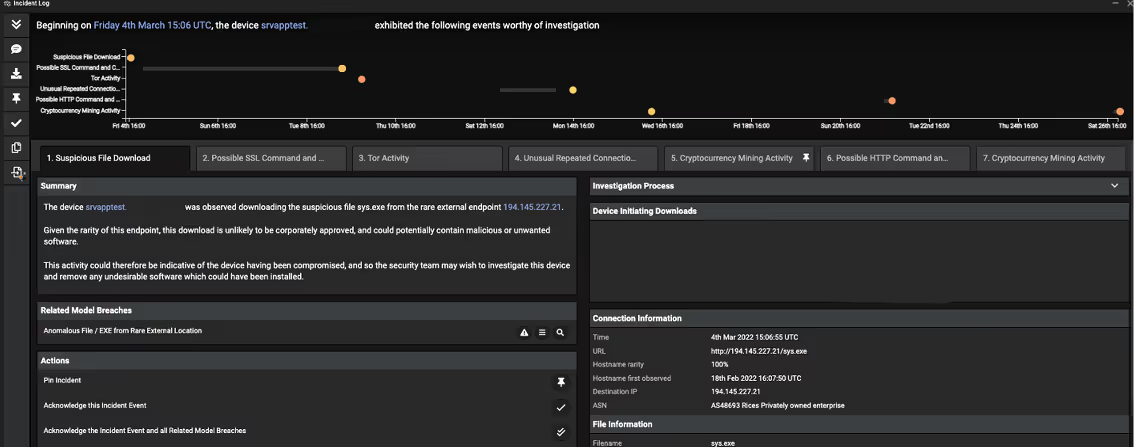

Cyber AI Analyst was able to connect the events and present them in a digestible, chronological order for the organization. In the aftermath of any security incidents, this is a convenient way for security users to conduct assisted investigations and reduce the workload on human analysts. However, it is good to note that this activity was also easily observed in real time from the model section on the Threat Visualizer due to the large number of escalating model breaches.

Figure 11: Cyber AI Analyst consolidating the events in the month of March into a summary

Figure 12: Cyber AI Analyst shows the progression of the attack through the month of March

As this incident occurred during a trial, Darktrace RESPOND was enabled in passive mode – with a valid license to display the actions that it would have taken, but with no active control performed. In this instance, no Antigena models breached for the initial compromised device as it was not tagged to be eligible for Antigena actions. Nonetheless, Darktrace was able to provide visibility into these anomalous connections.

Had Antigena been deployed in active mode, and the breach device appropriately tagged with Antigena All or Antigena External Threat, Darktrace would have been able to respond and neutralize different stages of the attack through network inhibitors Block Matching Connections and Enforce Group Pattern of Life, and relevant Antigena models such as Antigena Suspicious File Block, Antigena Suspicious File Pattern of Life Block, Antigena Pastebin Block and Antigena Crypto Currency Mining Block. The first of these inhibitors, Block Matching Connections, will block the specific connection and all future connections that matches the same criteria (e.g. all future outbound HTTP connections from the breach device to destination port 80) for a set period of time. Enforce Group Pattern of Life allows a device to only make connections and data transfers that it or any of its peer group typically make.

Conclusion

Resource hijacking results in unauthorized consumption of system resources and monetary loss for affected organizations. Compromised devices can potentially be rented out to other threat actors and botnet operators could switch from conducting crypto-mining to other more destructive illicit activities (e.g. DDoS or dropping of ransomware) whilst changing their TTPs in the future. Defenders are constantly playing catch-up to this continual evolution, and retrospective rules and signatures solutions or threat intelligence that relies on humans to spot future threats will not be able to keep up.

In this case, it appears the botnet operator has added an object query in the URL of the initial PowerShell loader script download, added Pastebin C2 for evasion and persistence, and utilized new cryptocurrency mining pools. Despite this, Darktrace’s Self-Learning AI was able to identify the threats the moment attackers changed their approach, detecting every step of the attack in the network without relying on known indicators of threat.

Appendix

Darktrace model detections

- Anomalous File / Script from Rare Location

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Medium Period)

- Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Device / External Address Scan

- Compromise / Crypto Currency Mining Activity

- Compromise / High Priority Crypto Currency Mining

- Compromise / High Volume of Connections with Beacon Score

- Compromise / SSL Beaconing to Rare Destination

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple HTTP POSTs to Rare Hostname

- Device / Large Number of Model Breaches

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

- Anomalous Connection / SSH Brute Force

- Compromise / SSH Beacon

- Compliance / SSH to Rare External AWS

- Compromise / High Frequency SSH Beacon

- Compliance / SSH to Rare External Destination

- Device / Multiple C2 Model Breaches

- Anomalous Connection / POST to PHP on New External Host

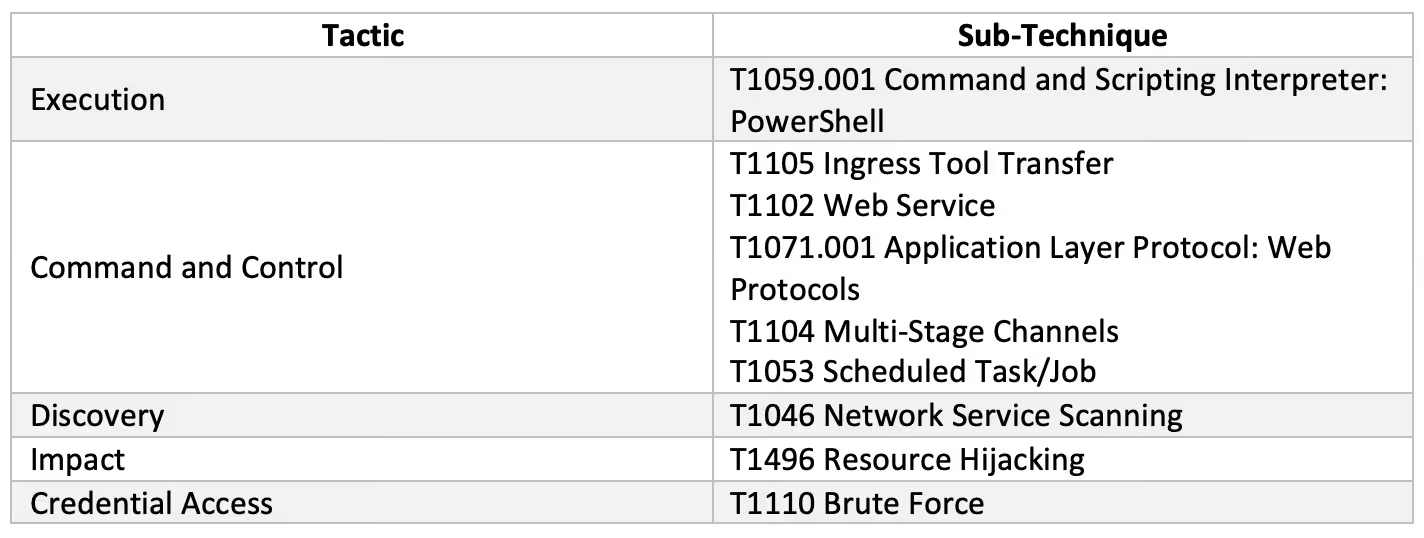

MITRE ATT&CK techniques observed:

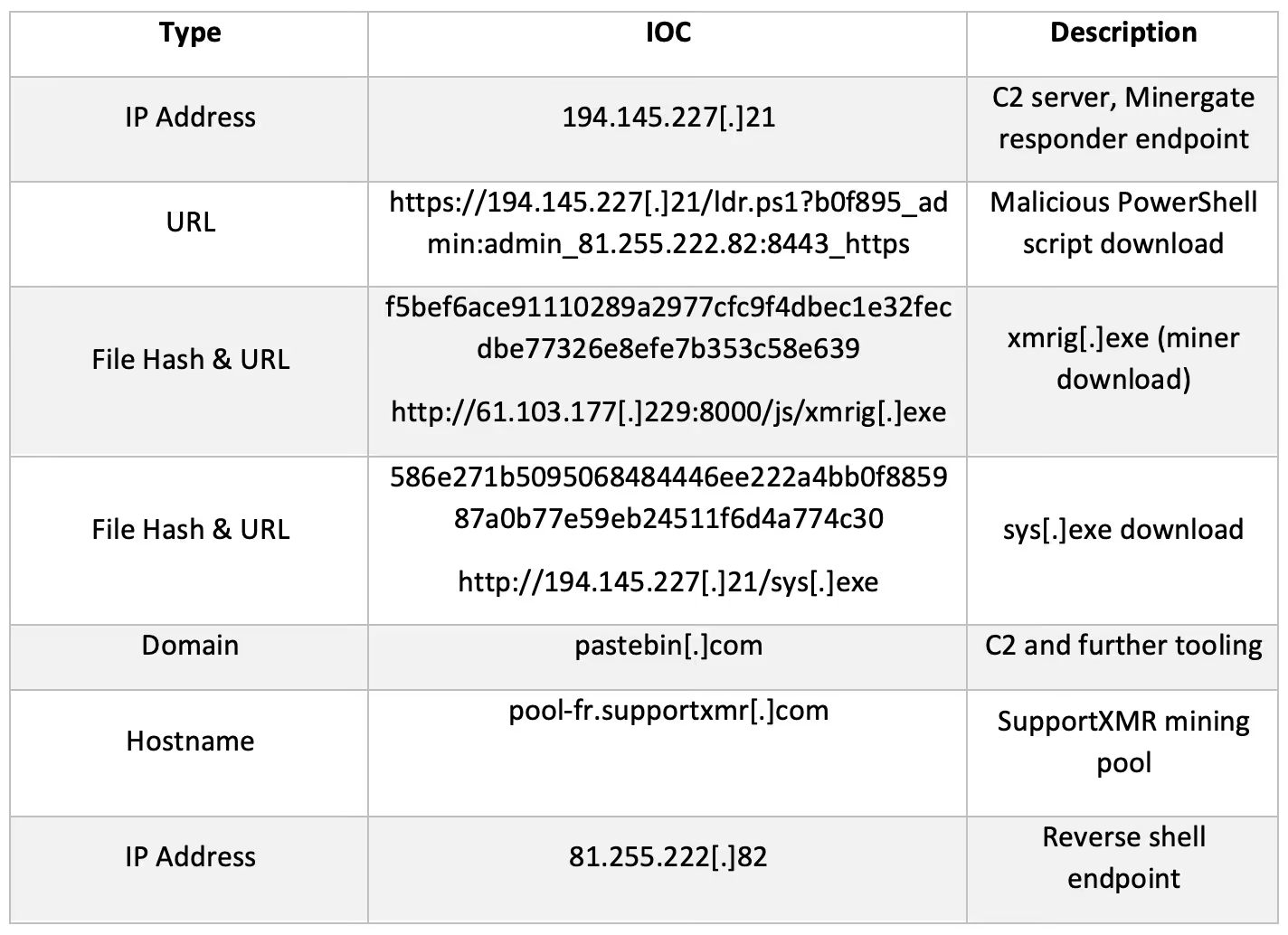

IoCs

Thanks to Victoria Baldie and Yung Ju Chua for their contributions.

Footnotes

1. https://www.darktrace.com/en/blog/crypto-botnets-moving-laterally

2. https://www.darktrace.com/en/blog/how-ai-uncovered-outlaws-secret-crypto-mining-operation

3. https://www.lacework.com/blog/sysrv-hello-expands-infrastructure

4. https://www.riskiq.com/blog/external-threat-management/sysrv-hello-cryptojacking-botnet

5. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/ip-address/194.145.227.21

6. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/url/c586845daa2aec275453659f287dcb302921321e04cb476b0d98d731d57c4e83?nocache=1

7. https://www.abuseipdb.com/check/81.255.222.82

8. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/586e271b5095068484446ee222a4bb0f885987a0b77e59eb24511f6d4a774c30

9. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/f5bef6ace91110289a2977cfc9f4dbec1e32fecdbe77326e8efe7b353c58e639

10. https://www.ironnet.com/blog/continued-exploitation-of-cve-2021-26084

11. https://www.zdnet.com/article/njrat-trojan-operators-are-now-using-pastebin-as-alternative-to-central-command-server

12. https://blogs.juniper.net/en-us/threat-research/sysrv-botnet-expands-and-gains-persistence

13. https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2017-9841

14. https://www.imperva.com/blog/the-resurrection-of-phpunit-rce-vulnerability

15. https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2021-3129

16. https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Laravel+v842+exploit+attempts+for+CVE20213129+debug+mode+Remote+code+execution/27758

17. https://securitynews.sonicwall.com/xmlpost/thinkphp-remote-code-execution-rce-bug-is-actively-being-exploited

18. https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2017-5638

19. https://sysdig.com/blog/crypto-sysrv-hello-wordpress