Introduction: AI & Cybersecurity

In the wake of artificial intelligence (AI) becoming more commonplace, it’s no surprise to see that threat actors are also adopting the use of AI in their attacks at an accelerated pace. AI enables augmentation of complex tasks such as spear-phishing, deep fakes, polymorphic malware generation, and advanced persistent threat (APT) campaigns, which significantly enhances the sophistication and scale of their operations. This has put security professionals in a reactive state, struggling to keep pace with the proliferation of threats.

As AI reshapes the future of cyber threats, defenders are also looking to integrate AI technologies into their security stack. Adopting AI-powered solutions in cybersecurity enables security teams to detect and respond to these advanced threats more quickly and accurately as well as automate traditionally manual and routine tasks. According to research done by Darktrace in the 2024 State of AI Cybersecurity Report improving threat detection, identifying exploitable vulnerabilities, and automating low level security tasks were the top three ways practitioners saw AI enhancing their security team’s capabilities [1], underscoring the wide-ranging capabilities of AI in cyber.

In this blog, we will discuss how AI has impacted the threat landscape, the rise of generative AI and AI adoption in security tools, and the importance of using multiple types of AI in cybersecurity solutions for a holistic and proactive approach to keeping your organization safe.

The impact of AI on the threat landscape

The integration of AI and cybersecurity has brought about significant advancements across industries. However, it also introduces new security risks that challenge traditional defenses. Three major concerns with the misuse of AI being leveraged by adversaries are: (1) the increase of novel social engineering attacks that are harder to detect and able to bypass traditional security tools, (2) the ease of access for less experienced threat actors to now deliver advanced attacks at speed and scale and (3) the attacking of AI itself, to include machine learning models, data corpuses and APIs or interfaces.

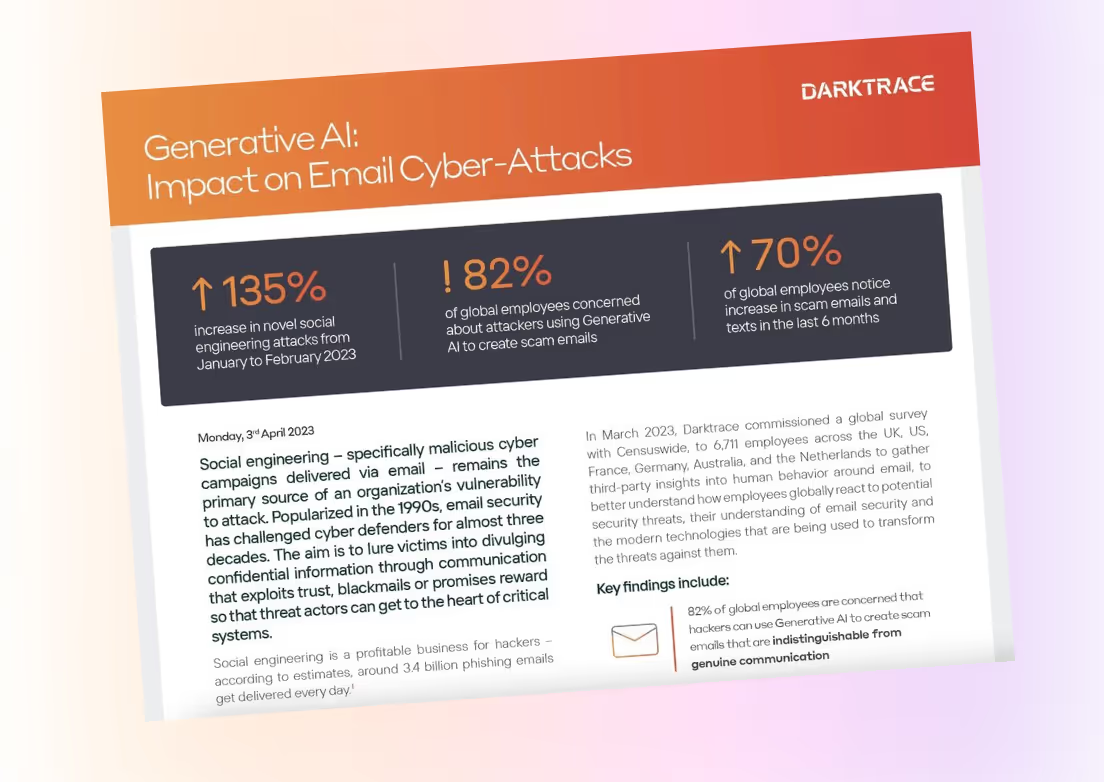

In the context of social engineering, AI can be used to create more convincing phishing emails, conduct advanced reconnaissance, and simulate human-like interactions to deceive victims more effectively. Generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT, are already being used by adversaries to craft these sophisticated phishing emails, which can more aptly mimic human semantics without spelling or grammatical error and include personal information pulled from internet sources such as social media profiles. And this can all be done at machine speed and scale. In fact, Darktrace researchers observed a 135% rise in ‘novel social engineering attacks’ across Darktrace / EMAIL customers in 2023, corresponding to the widespread adoption and use of ChatGPT [2].

Furthermore, these sophisticated social engineering attacks are now able to circumvent traditional security tools. In between December 21, 2023, and July 5, 2024, Darktrace / EMAIL detected 17.8 million phishing emails across the fleet, with 62% of these phishing emails successfully bypassing Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance (DMARC) verification checks [2].

And while the proliferation of novel attacks fueled by AI is persisting, AI also lowers the barrier to entry for threat actors. Publicly available AI tools make it easy for adversaries to automate complex tasks that previously required advanced technical skills. Additionally, AI-driven platforms and phishing kits available on the dark web provide ready-made solutions, enabling even novice attackers to execute effective cyber campaigns with minimal effort.

The impact of adversarial use of AI on the ever-evolving threat landscape is important for organizations to understand as it fundamentally changes the way we must approach cybersecurity. However, while the intersection of cybersecurity and AI can have potentially negative implications, it is important to recognize that AI can also be used to help protect us.

A generation of generative AI in cybersecurity

When the topic of AI in cybersecurity comes up, it’s typically in reference to generative AI, which became popularized in 2023. While it does not solely encapsulate what AI cybersecurity is or what AI can do in this space, it’s important to understand what generative AI is and how it can be implemented to help organizations get ahead of today’s threats.

Generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT or Microsoft Copilot) is a type of AI that creates new or original content. It has the capability to generate images, videos, or text based on information it learns from large datasets. These systems use advanced algorithms and deep learning techniques to understand patterns and structures within the data they are trained on, enabling them to generate outputs that are coherent, contextually relevant, and often indistinguishable from human-created content.

For security professionals, generative AI offers some valuable applications. Primarily, it’s used to transform complex security data into clear and concise summaries. By analyzing vast amounts of security logs, alerts, and technical data, it can contextualize critical information quickly and present findings in natural, comprehensible language. This makes it easier for security teams to understand critical information quickly and improves communication with non-technical stakeholders. Generative AI can also automate the creation of realistic simulations for training purposes, helping security teams prepare for various cyberattack scenarios and improve their response strategies.

Despite its advantages, generative AI also has limitations that organizations must consider. One challenge is the potential for generating false positives, where benign activities are mistakenly flagged as threats, which can overwhelm security teams with unnecessary alerts. Moreover, implementing generative AI requires significant computational resources and expertise, which may be a barrier for some organizations. It can also be susceptible to prompt injection attacks and there are risks with intellectual property or sensitive data being leaked when using publicly available generative AI tools. In fact, according to the MIT AI Risk Registry, there are potentially over 700 risks that need to be mitigated with the use of generative AI.

For more information on generative AI's impact on the cyber threat landscape download the Darktrace Data Sheet

Beyond the Generative AI Glass Ceiling

Generative AI has a place in cybersecurity, but security professionals are starting to recognize that it’s not the only AI organizations should be using in their security tool kit. In fact, according to Darktrace’s State of AI Cybersecurity Report, “86% of survey participants believe generative AI alone is NOT enough to stop zero-day threats.” As we look toward the future of AI in cybersecurity, it’s critical to understand that different types of AI have different strengths and use cases and choosing the technologies based on your organization’s specific needs is paramount.

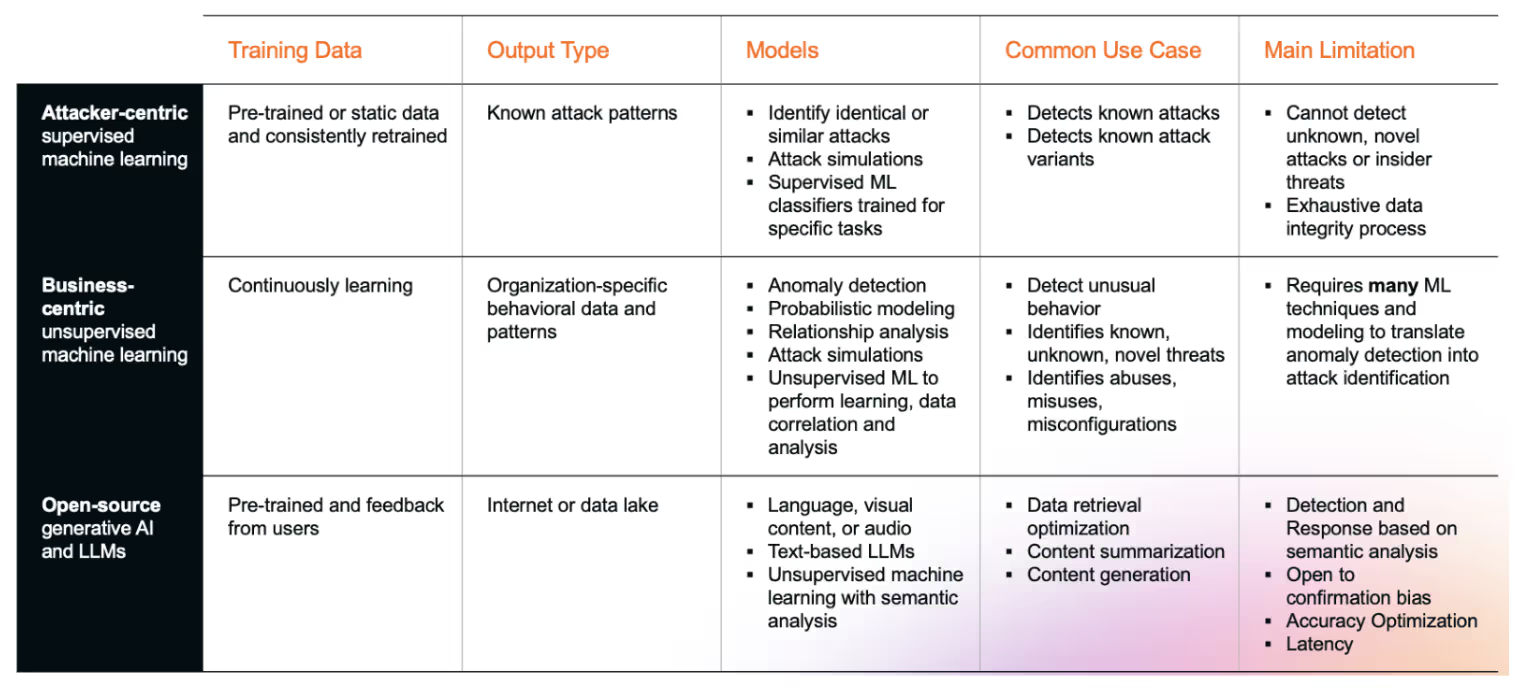

There are a few types of AI used in cybersecurity that serve different functions. These include:

Supervised Machine Learning: Widely used in cybersecurity due to its ability to learn from labeled datasets. These datasets include historical threat intelligence and known attack patterns, allowing the model to recognize and predict similar threats in the future. For example, supervised machine learning can be applied to email filtering systems to identify and block phishing attempts by learning from past phishing emails. This is human-led training facilitating automation based on known information.

Large Language Models (LLMs): Deep learning models trained on extensive datasets to understand and generate human-like text. LLMs can analyze vast amounts of text data, such as security logs, incident reports, and threat intelligence feeds, to identify patterns and anomalies that may indicate a cyber threat. They can also generate detailed and coherent reports on security incidents, summarizing complex data into understandable formats.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): Involves the application of computational techniques to process and understand human language. In cybersecurity, NLP can be used to analyze and interpret text-based data, such as emails, chat logs, and social media posts, to identify potential threats. For instance, NLP can help detect phishing attempts by analyzing the language used in emails for signs of deception.

Unsupervised Machine Learning: Continuously learns from raw, unstructured data without predefined labels. It is particularly useful in identifying new and unknown threats by detecting anomalies that deviate from normal behavior. In cybersecurity, unsupervised learning can be applied to network traffic analysis to identify unusual patterns that may indicate a cyberattack. It can also be used in endpoint detection and response (EDR) systems to uncover previously unknown malware by recognizing deviations from typical system behavior.

Employing multiple types of AI in cybersecurity is essential for creating a layered and adaptive defense strategy. Each type of AI, from supervised and unsupervised machine learning to large language models (LLMs) and natural language processing (NLP), brings distinct capabilities that address different aspects of cyber threats. Supervised learning excels at recognizing known threats, while unsupervised learning uncovers new anomalies. LLMs and NLP enhance the analysis of textual data for threat detection and response and aid in understanding and mitigating social engineering attacks. By integrating these diverse AI technologies, organizations can achieve a more holistic and resilient cybersecurity framework, capable of adapting to the ever-evolving threat landscape.

A Multi-Layered AI Approach with Darktrace

AI-powered security solutions are emerging as a crucial line of defense against an AI-powered threat landscape. In fact, “Most security stakeholders (71%) are confident that AI-powered security solutions will be better able to block AI-powered threats than traditional tools.” And 96% agree that AI-powered solutions will level up their organization’s defenses. As organizations look to adopt these tools for cybersecurity, it’s imperative to understand how to evaluate AI vendors to find the right products as well as build trust with these AI-powered solutions.

Darktrace, a leader in AI cybersecurity since 2013, emphasizes interpretability, explainability, and user control, ensuring that our AI is understandable, customizable and transparent. Darktrace’s approach to cyber defense is rooted in the belief that the right type of AI must be applied to the right use cases. Central to this approach is Self-Learning AI, which is crucial for identifying novel cyber threats that most other tools miss. This is complemented by various AI methods, including LLMs, generative AI, and supervised machine learning, to support the Self-Learning AI.

Darktrace focuses on where AI can best augment the people in a security team and where it can be used responsibly to have the most positive impact on their work. With a combination of these AI techniques, applied to the right use cases, Darktrace enables organizations to tailor their AI defenses to unique risks, providing extended visibility across their entire digital estates with the Darktrace ActiveAI Security Platform™.

Credit to: Ed Metcalf, Senior Director Product Marketing, AI & Innovations - Nicole Carignan VP of Strategic Cyber AI for their contribution to this blog.

To learn more about Darktrace and AI in cybersecurity download the CISO’s Guide to Cyber AI here.

Download the white paper to learn how buyers should approach purchasing AI-based solutions. It includes:

- Key steps for selecting AI cybersecurity tools

- Questions to ask and responses to expect from vendors

- Understand tools available and find the right fit

- Ensure AI investments align with security goals and needs

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)