Introduction

The aim of this blog is to be an educational resource, documenting how an analyst can perform malware analysis techniques such as unpacking. This blog will demonstrate the malware analysis process against well-known malware, in this case SnappyBee.

SnappyBee (also known as Deed RAT) is a modular backdoor that has been previously attributed to China-linked cyber espionage group Salt Typhoon, also known as Earth Estries [1] [2]. The malware was first publicly documented by TrendMicro in November 2024 as part of their investigation into long running campaigns targeting various industries and governments by China-linked threat groups.

In these campaigns, SnappyBee is deployed post-compromise, after the attacker has already obtained access to a customer's system, and is used to establish long-term persistence as well as deploying further malware such as Cobalt Strike and the Demodex rootkit.

To decrease the chance of detection, SnappyBee uses a custom packing routine. Packing is a common technique used by malware to obscure its true payload by hiding it and then stealthily loading and executing it at runtime. This hinders analysis and helps the malware evade detection, especially during static analysis by both human analysts and anti-malware services.

This blog is a practical guide on how an analyst can unpack and analyze SnappyBee, while also learning the necessary skills to triage other malware samples from advanced threat groups.

First principles

Packing is not a new technique, and threat actors have generally converged on a standard approach. Packed binaries typically feature two main components: the packed data and an unpacking stub, also called a loader, to unpack and run the data.

Typically, malware developers insert a large blob of unreadable data inside an executable, such as in the .rodata section. This data blob is the true payload of the malware, but it has been put through a process such as encryption, compression, or another form of manipulation to render it unreadable. Sometimes, this data blob is instead shipped in a different file, such as a .dat file, or a fake image. When this happens, the main loader has to read this using a syscall, which can be useful for analysis as syscalls can be easily identified, even in heavily obfuscated binaries.

In the main executable, malware developers will typically include an unpacking stub that takes the data blob, performs one or more operations on it, and then triggers its execution. In most samples, the decoded payload data is loaded into a newly allocated memory region, which will then be marked as executable and executed. In other cases, the decoded data is instead dropped into a new executable on disk and run, but this is less common as it increases the likelihood of detection.

Finding the unpacking routine

The first stage of analysis is uncovering the unpacking routine so it can be reverse engineered. There are several ways to approach this, but it is traditionally first triaged via static analysis on the initial stages available to the analyst.

SnappyBee consists of two components that can be analyzed:

- A Dynamic-link Library (DLL) that acts as a loader, responsible for unpacking the malicious code

- A data file shipped alongside the DLL, which contains the encrypted malicious code

Additionally, SnappyBee includes a legitimate signed executable that is vulnerable to DLL side-loading. This means that when the executable is run, it will inadvertently load SnappyBee’s DLL instead of the legitimate one it expects. This allows SnappyBee to appear more legitimate to antivirus solutions.

The first stage of analysis is performing static analysis of the DLL. This can be done by opening the DLL within a disassembler such as IDA Pro. Upon opening the DLL, IDA will display the DllMain function, which is the malware’s initial entry point and the first code executed when the DLL is loaded.

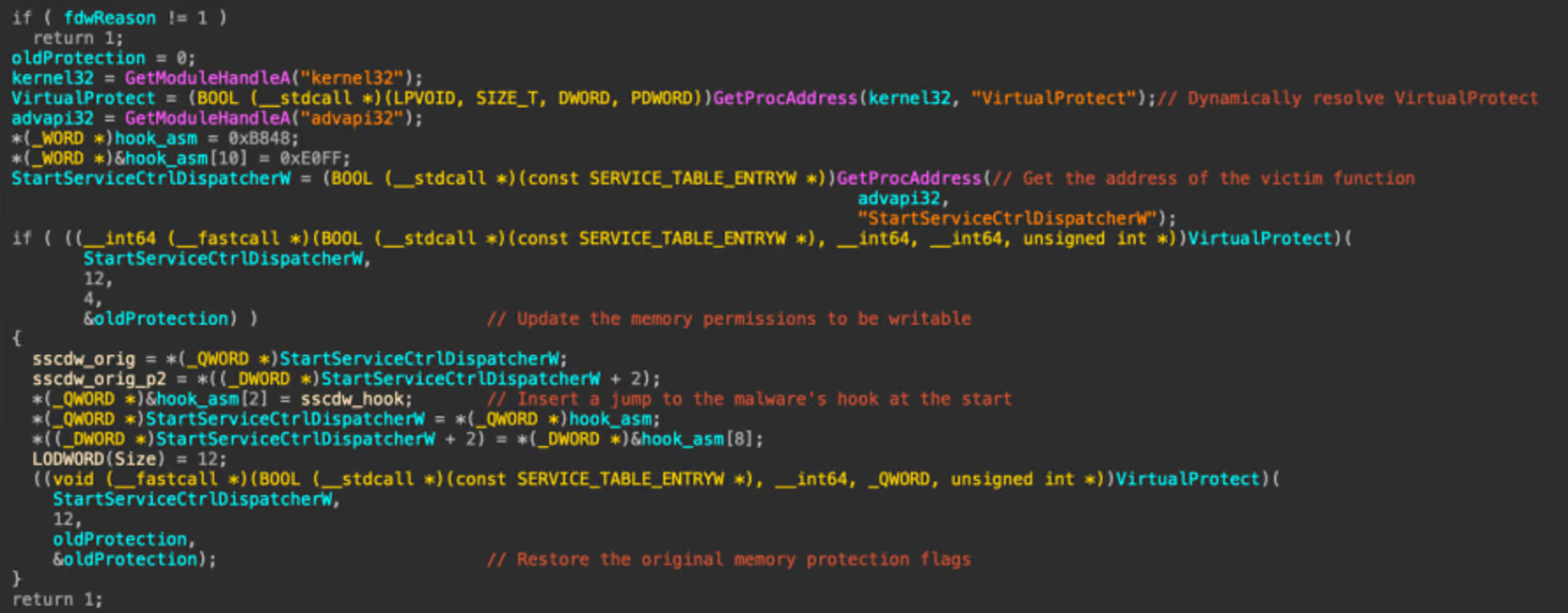

First, the function checks if the variable fdwReason is set to 1, and exits if it is not. This variable is set by Windows to indicate why the DLL was loaded. According to Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN), a value of 1 corresponds to DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH, meaning “The DLL is being loaded into the virtual address space of the current process as a result of the process starting up or as a result of a call to LoadLibrary” [3]. Since SnappyBee is known to use DLL sideloading for execution, DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH is the expected value when the legitimate executable loads the malicious DLL.

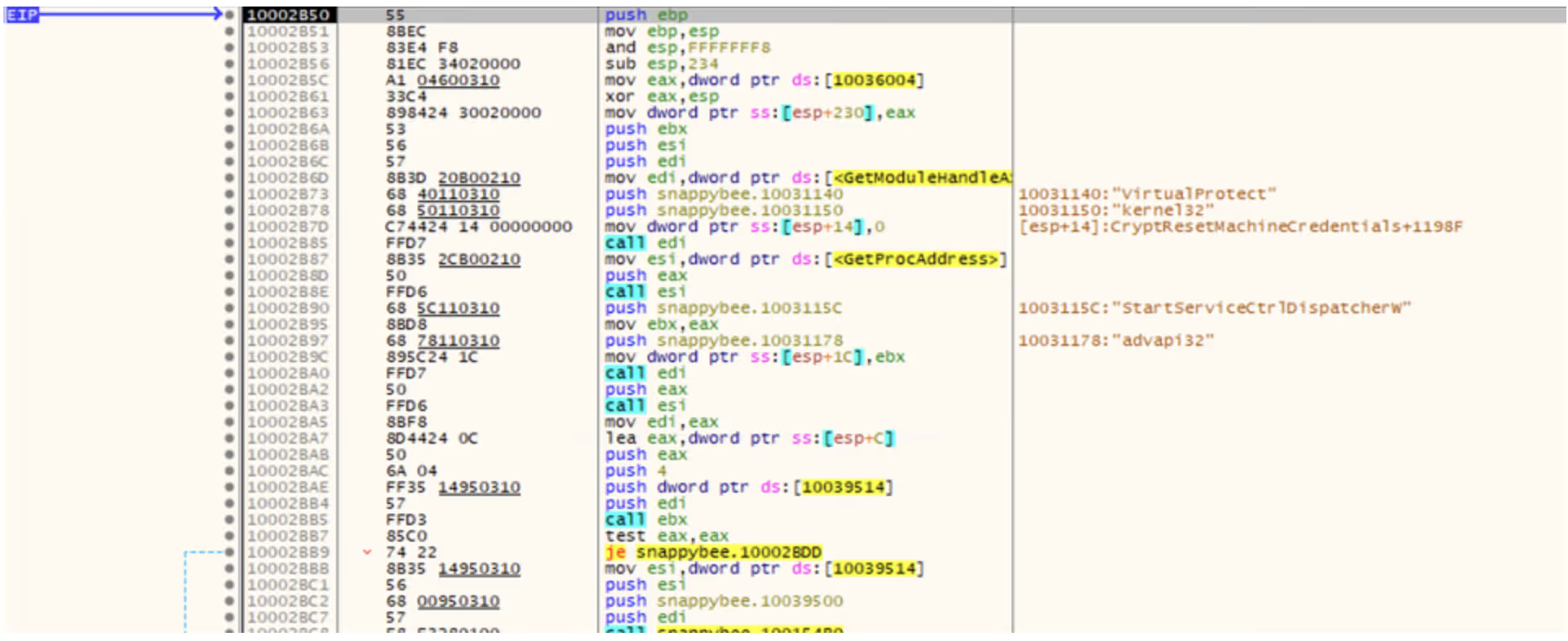

SnappyBee then uses the GetModule and GetProcAddress to dynamically resolve the address of the VirtualProtect in kernel32 and StartServiceCtrlDispatcherW in advapi32. Resolving these dynamically at runtime prevents them from showing up as a static import for the module, which can help evade detection by anti-malware solutions. Different regions of memory have different permissions to control what they can be used for, with the main ones being read, write, and execute. VirtualProtect is a function that changes the permissions of a given memory region.

SnappyBee then uses VirtualProtect to set the memory region containing the code for the StartServiceCtrlDispatcherW function as writable. It then inserts a jump instruction at the start of this function, redirecting the control flow to one of the SnappyBee DLL’s other functions, and then restores the old permissions.

In practice, this means when the legitimate executable calls StartServiceCtrlDispatcherW, it will immediately hand execution back to SnappyBee. Meanwhile, the call stack now appears more legitimate to outside observers such as antimalware solutions.

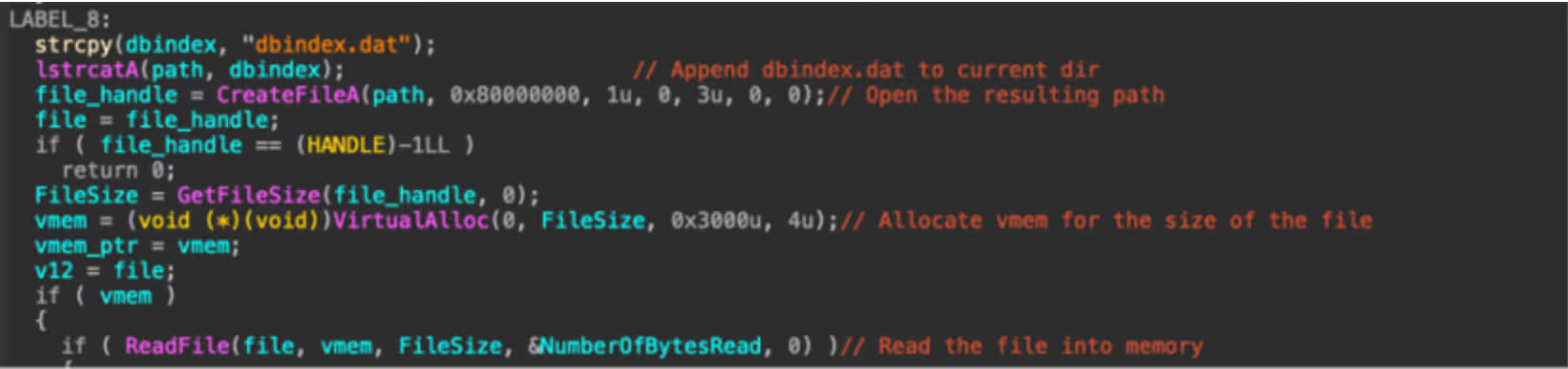

The hooked-in function then reads the data file that is shipped with SnappyBee and loads it into a new memory allocation. This pattern of loading the file into memory likely means it is responsible for unpacking the next stage.

SnappyBee then proceeds to decrypt the memory allocation and execute the code.

This section may look complex, however it is fairly straight forward. Firstly, it uses memset to zero out a stack variable, which will be used to store the decryption key. It then uses the first 16 bytes of the data file as a decryption key to initialize the context from.

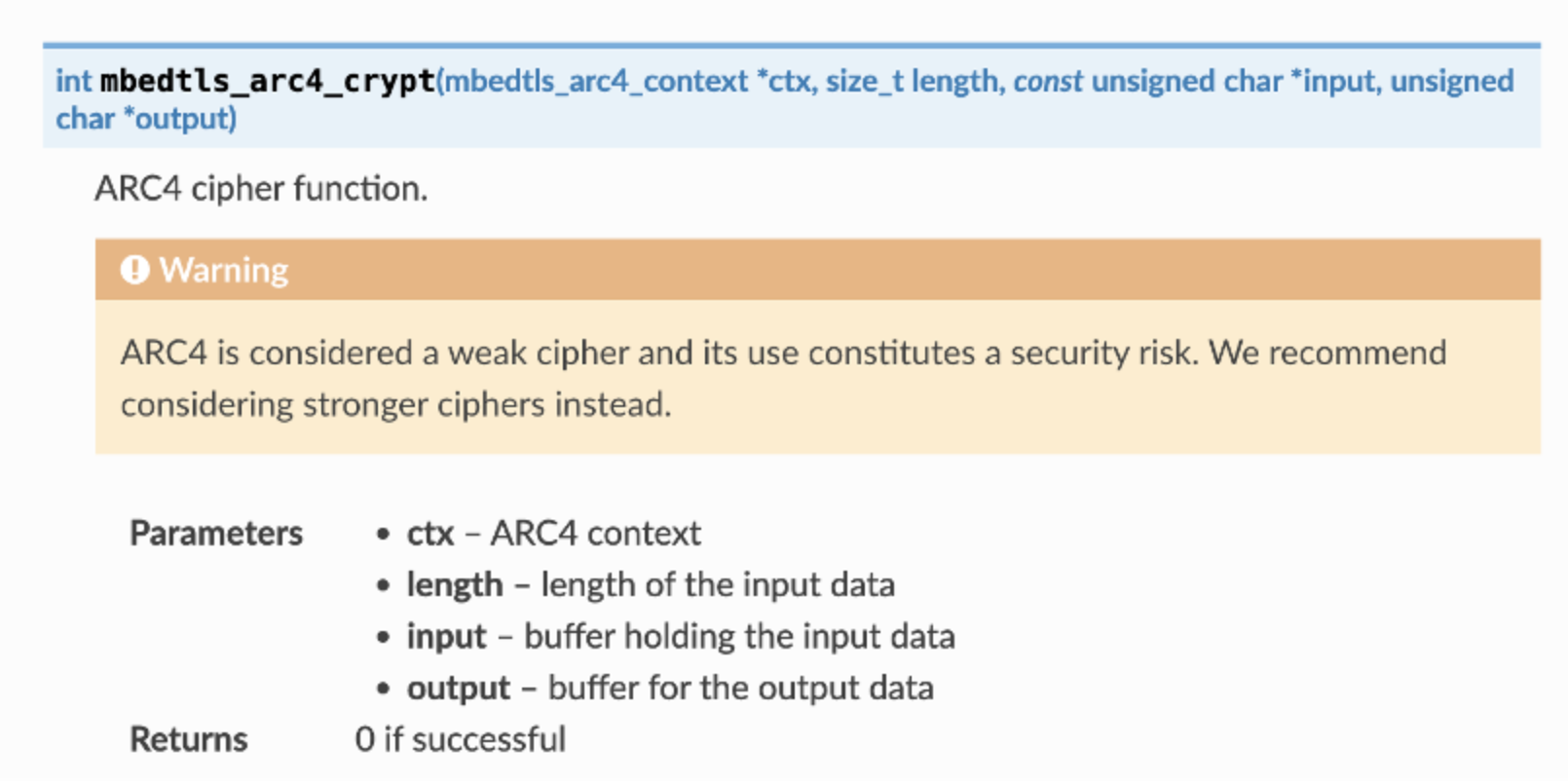

SnappyBee then calls the mbed_tls_arc4_crypt function, which is a function from the mbedtls library. Documentation for this function can be found online and can be referenced to better understand what each of the arguments mean [4].

Comparing the decompilation with the documentation, the arguments SnappyBee passes to the function can be decoded as:

- The context derived from 16-byte key at the start of the data is passed in as the context in the first parameter

- The file size minus 16 bytes (to account for the key at the start of the file) is the length of the data to be decrypted

- A pointer to the file contents in memory, plus 16 bytes to skip the key, is used as the input

- A pointer to a new memory allocation obtained from VirtualAlloc is used as the output

So, putting it all together, it can be concluded that SnappyBee uses the first 16 bytes as the key to decrypt the data that follows , writing the output into the allocated memory region.

SnappyBee then calls VirtualProtect to set the decrypted memory region as Read + Execute, and subsequently executes the code at the memory pointer. This is clearly where the unpacked code containing the next stage will be placed.

Unpacking the malware

Understanding how the unpacking routine works is the first step. The next step is obtaining the actual code, which cannot be achieved through static analysis alone.

There are two viable methods to retrieve the next stage. The first method is implementing the unpacking routine from scratch in a language like Python and running it against the data file.

This is straightforward in this case, as the unpacking routine in relatively simple and would not require much effort to re-implement. However, many unpacking routines are far more complex, which leads to the second method: allowing the malware to unpack itself by debugging it and then capturing the result. This is the approach many analysts take to unpacking, and the following will document this method to unpack SnappyBee.

As SnappyBee is 32-bit Windows malware, debugging can be performed using x86dbg in a Windows sandbox environment to debug SnappyBee. It is essential this sandbox is configured correctly, because any mistake during debugging could result in executing malicious code, which could have serious consequences.

Before debugging, it is necessary to disable the DYNAMIC_BASE flag on the DLL using a tool such as setdllcharacteristics. This will stop ASLR from randomizing the memory addresses each time the malware runs and ensures that it matches the addresses observed during static analysis.

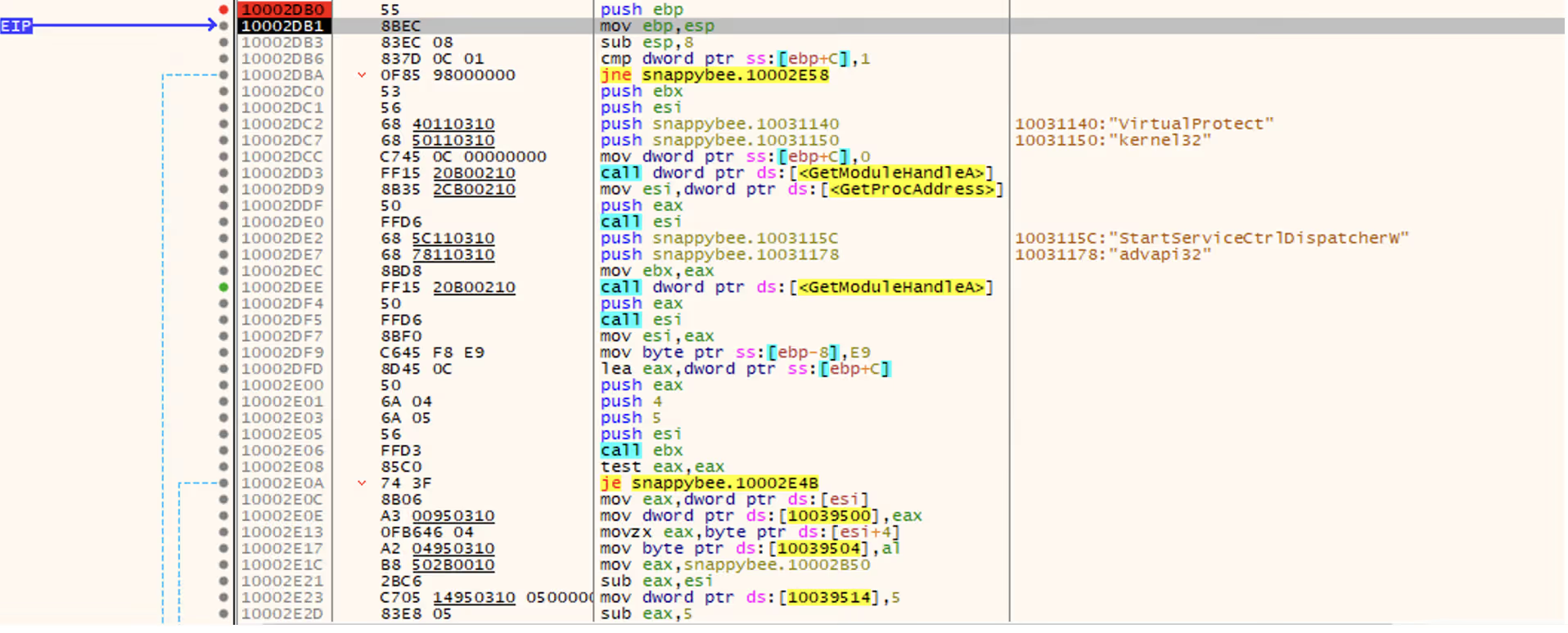

The first place to set a breakpoint is DllMain, as this is the start of the malicious code and the logical place to pause before proceeding. Using IDA, the functions address can be determined; in this case, it is at offset 10002DB0. This can be used in the Goto (CTRL+G) dialog to jump to the offset and place a breakpoint. Note that the “Run to user code” button may need to be pressed if the DLL has not yet been loaded by x32dbg, as it spawns a small process to load the DLL as DLLs cannot be executed directly.

The program can then run until the breakpoint, at which point the program will pause and code recognizable from static analysis can be observed.

In the previous section, this function was noted as responsible for setting up a hook, and in the disassembly listing the hook address can be seen being loaded at offset 10002E1C. It is not necessary to go through the whole hooking process, because only the function that gets hooked in needs to be run. This function will not be naturally invoked as the DLL is being loaded directly rather than via sideloading as it expects. To work around this, the Extended Instruction Pointer (EIP) register can be manipulated to point to the start of the hook function instead, which will cause it to run instead of the DllMain function.

To update EIP, the CRTL+G dialog can again be used to jump to the hook function address (10002B50), and then the EIP register can be set to this address by right clicking the first instruction and selecting “Set EIP here”. This will make the hook function code run next.

Once in this function, there are a few addresses where breakpoints should be set in order to inspect the state of the program at critical points in the unpacking process. These are:

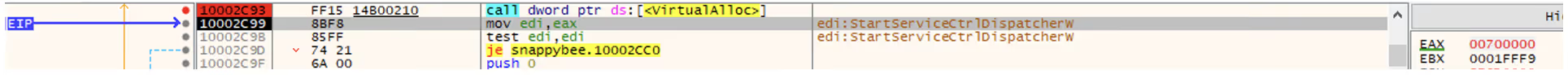

- 10002C93, which allocates the memory for the data file and final code

- 10002D2D, which decrypts the memory

- 10002D81, which runs the unpacked code

Setting these can be done by pressing the dot next to the instruction listing, or via the CTRL+G Goto menu.

At the first breakpoint, the call to VirtualAlloc will be executed. The function returns the memory address of the created memory region, which is stored in the EAX register. In this case, the region was allocated at address 00700000.

It is possible to right click the address and press “Follow in dump” to pin the contents of the memory to the lower pane, which makes it easy to monitor the region as the unpacking process continues.

Single-stepping through the application from this point eventually reaches the call to ReadFile, which loads the file into the memory region.

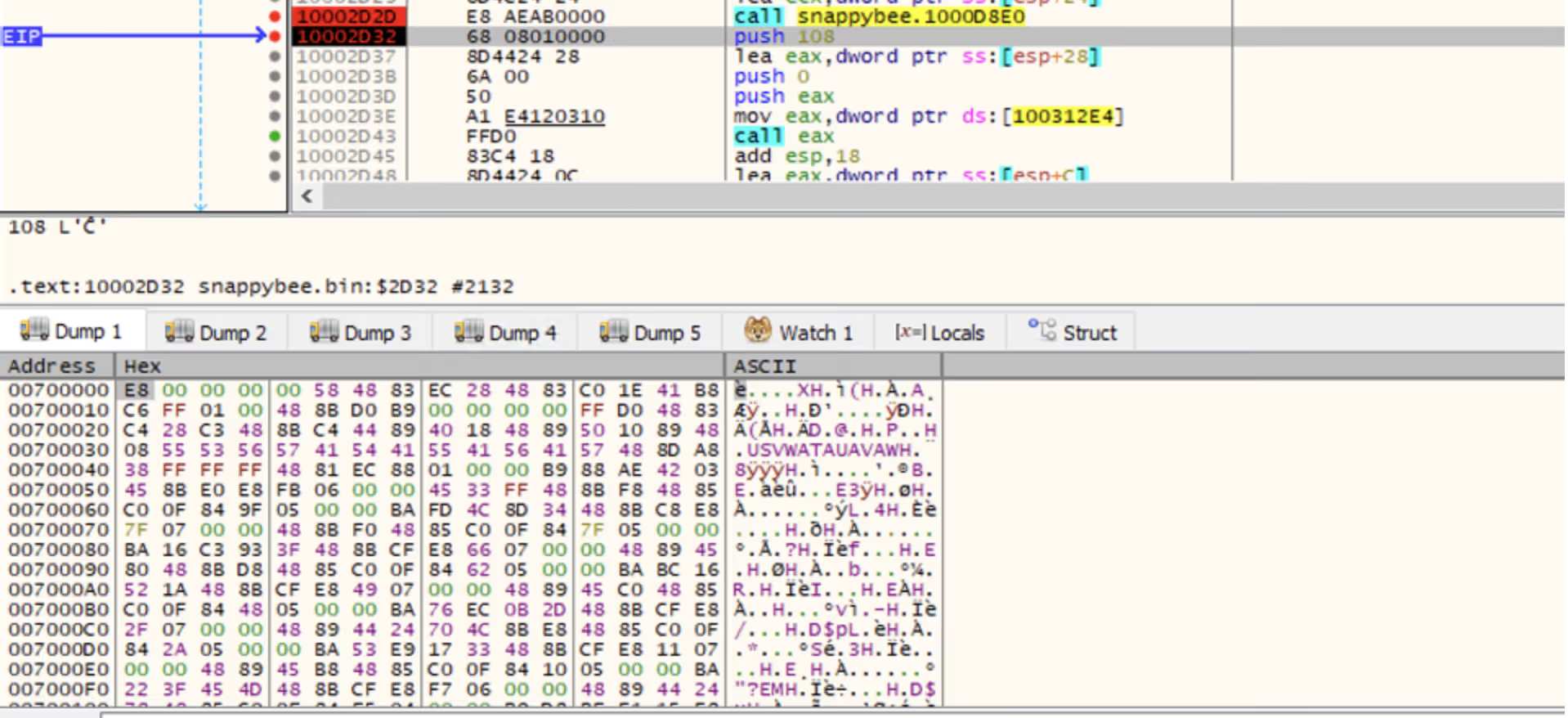

The program can then be allowed to run until the next breakpoint, which after single-stepping will execute the call to mbedtls_arc4_crypt to decrypt the memory. At this point, the data in the dump will have changed.

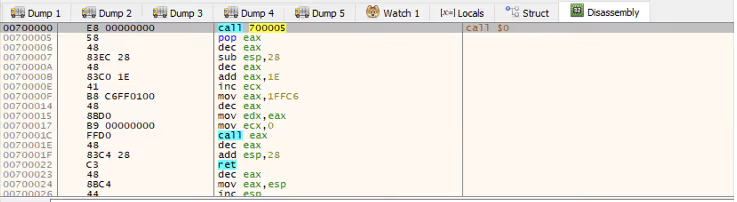

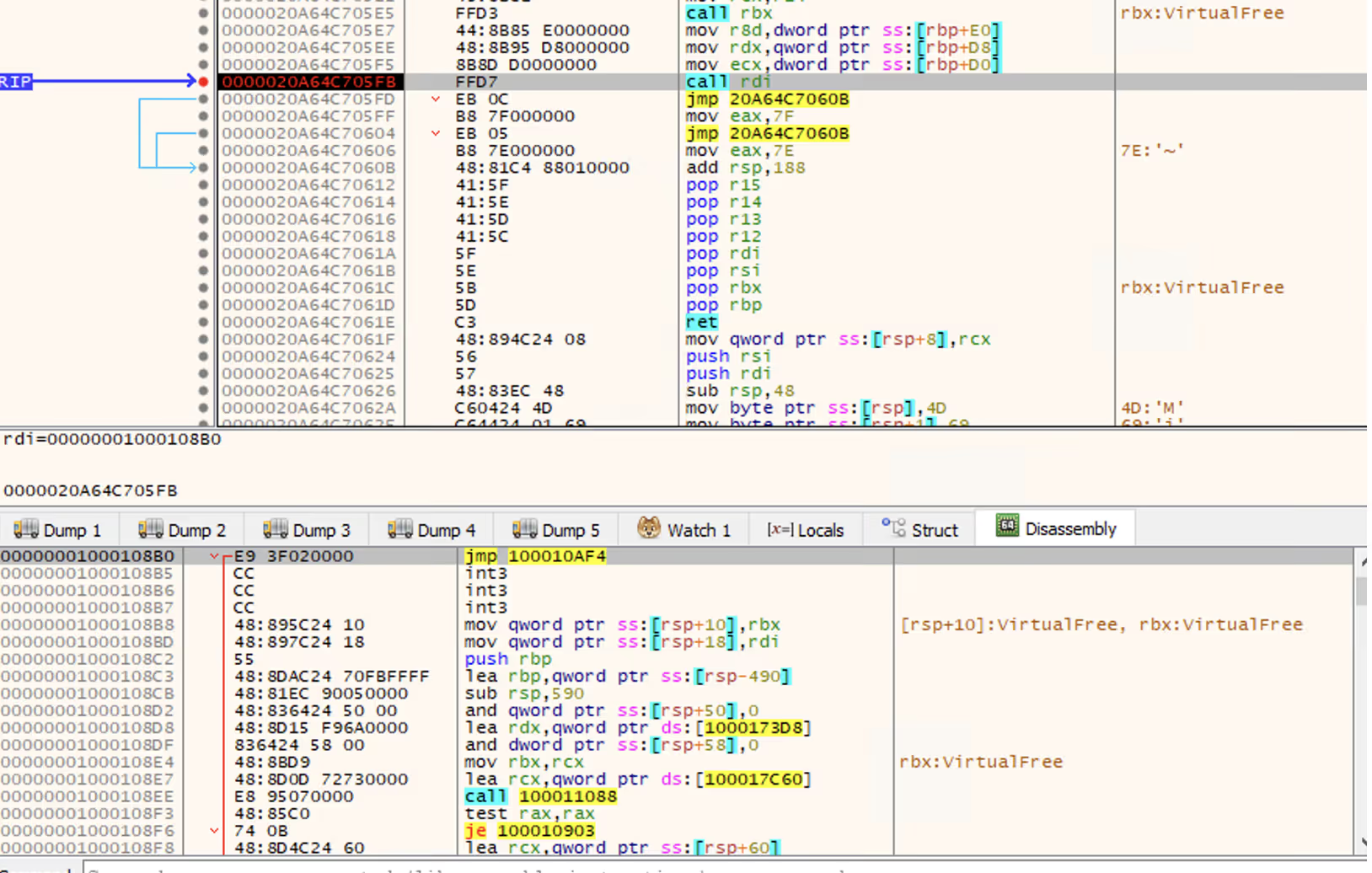

Right-clicking in the dump and selecting "Disassembly” will disassemble the data. This yields valid shell code, indicating that the unpacking succeeded, whereas corrupt or random data would be expected if the unpacking had failed.

Right-clicking and selecting “Follow in memory map” will show the memory allocation under the memory map view. Right-clicking this then provides an option to dump the entire memory block to file.

This dump can then be opened in IDA, enabling further static analysis of the shellcode. Reviewing the shellcode, it becomes clear that it performs another layer of unpacking.

As the debugger is already running, the sample can be allowed to execute up to the final breakpoint that was set on the call to the unpacked shellcode. Stepping into this call will then allow debugging of the new shellcode.

The simplest way to proceed is to single-step through the code, pausing on each call instruction to consider its purpose. Eventually, a call instruction that points to one of the memory regions that were assigned will be reached, which will contain the next layer of unpacked code. Using the same disassembly technique as before, it can be confirmed that this is more unpacked shellcode.

Once again, this can be dumped out and analyzed further in IDA. In this case, it is the final payload used by the SnappyBee malware.

Conclusion

Unpacking remains one of the most common anti-analysis techniques and is a feature of most sophisticated malware from threat groups. This technique of in-memory decryption reduces the forensic “surface area” of the malware, helping it to evade detection from anti-malware solutions. This blog walks through one such example and provides practical knowledge on how to unpack malware for deeper analysis.

In addition, this blog has detailed several other techniques used by threat actors to evade analysis, such as DLL sideloading to execute code without arising suspicion, dynamic API resolving to bypass static heuristics, and multiple nested stages to make analysis challenging.

Malware such as SnappyBee demonstrates a continued shift towards highly modular and low-friction malware toolkits that can be reused across many intrusions and campaigns. It remains vital for security teams to maintain the ability to combat the techniques seen in these toolkits when responding to infections.

While the technical details of these techniques are primarily important to analysts, the outcomes of this work directly affect how a Security Operations Centre (SOC) operates at scale. Without the technical capability to reliably unpack and observe these samples, organizations are forced to respond without the full picture.

The techniques demonstrated here help close that gap. This enables security teams to reduce dwell time by understanding the exact mechanisms of a sample earlier, improve detection quality with behavior-based indicators rather than relying on hash-based detections, and increase confidence in response decisions when determining impact.

Credit to Nathaniel Bill (Malware Research Engineer)

Edited by Ryan Traill (Analyst Content Lead)

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

SnappyBee Loader 1 - 25b9fdef3061c7dfea744830774ca0e289dba7c14be85f0d4695d382763b409b

SnappyBee Loader 2 - b2b617e62353a672626c13cc7ad81b27f23f91282aad7a3a0db471d84852a9ac

SnappyBee Payload - 1a38303fb392ccc5a88d236b4f97ed404a89c1617f34b96ed826e7bb7257e296

References

[1] https://www.trendmicro.com/en_gb/research/24/k/earth-estries.html

[2] https://www.darktrace.com/blog/salty-much-darktraces-view-on-a-recent-salt-typhoon-intrusion

[3] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/dlls/dllmain#parameters