What is Scattered Spider?

Scattered Spider is a native English-speaking group, also referred to, or closely associated with, aliases such as UNC3944, Octo Tempest and Storm-0875. They are primarily financially motivated with a clear emphasis on leveraging social engineering, SIM swapping attacks, exploiting legitimate tooling as well as using Living-Off-the-Land (LOTL) techniques [1][2].

In recent years, Scattered Spider has been observed employing a shift in tactics, leveraging Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) platforms in their attacks. This adoption reflects a shift toward more scalable attacks with a lower barrier to entry, allowing the group to carry out sophisticated ransomware attacks without the need to develop it themselves.

While RaaS offerings have been available for purchase on the Dark Web for several years, they have continued to grow in popularity, providing threat actors a way to cause significant impact to critical infrastructure and organizations without requiring highly technical capabilities [12].

This blog focuses on the group’s recent changes in tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) reported by open-source intelligence (OSINT) and how TTPs in a recent Scattered Spider attack observed by Darktrace compare.

How has Scattered Spider been reported to operate?

First observed in 2022, Scattered Spider is known to target various industries globally including telecommunications, technology, financial services, and commercial facilities.

Overview of key TTPs

Scattered Spider has been known to utilize the following methods which cover multiple stages of the Cyber Kill Chain including initial access, lateral movement, evasion, persistence, and action on objective:

Social engineering [1]:

Impersonating staff via phone calls, SMS and Telegram messages; obtaining employee credentials (MITRE techniques T1598,T1656), multi-factor authentication (MFA) codes such as one-time passwords, or convincing employees to run commercial remote access tools enabling initial access (MITRE techniques T1204,T1219,T1566)

- Phishing using specially crafted domains containing the victim name e.g. victimname-sso[.]com

- MFA fatigue: sending repeated requests for MFA approval with the intention that the victim will eventually accept (MITRE technique T1621)

SIM swapping [1][3]:

- Includes hijacking phone numbers to intercept 2FA codes

- This involves the actor migrating the victim's mobile number to a new SIM card without legitimate authorization

Reconnaissance, lateral movement & command-and-control (C2) communication via use of legitimate tools:

- Examples include Mimikatz, Ngrok, TeamViewer, and Pulseway [1]. A more recently reported example is Teleport [3].

Financial theft through their access to victim networks: Extortion via ransomware, data theft (MITRE technique T1657) [1]

Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD) techniques [4]:

- Exploiting vulnerable drivers to evade detection from Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) security products (MITRE technique T1068) frequently used against Windows devices.

LOTL techniques

LOTL techniques are also closely associated with Scattered Spider actors once they have gained initial access; historically this has allowed them to evade detection until impact starts to be felt. It also means that specific TTPs may vary from case-to-case, making it harder for security teams to prepare and harden defences against the group.

Prominent Scattered Spider attacks over the years

While attribution is sometimes unconfirmed, Scattered Spider have been linked with a number of highly publicized attacks since 2022.

Smishing attacks on Twilio: In August 2022 the group conducted multiple social engineering-based attacks. One example was an SMS phishing (smishing) attack against the cloud communication platform Twilio, which led to the compromise of employee accounts, allowing actors to access internal systems and ultimately target Twilio customers [5][6].

Phishing and social engineering against MailChimp: Another case involved a phishing and social engineering attack against MailChimp. After gaining access to internal systems through compromised employee accounts the group conducted further attacks specifically targeting MailChimp users within cryptocurrency and finance industries [5][7].

Social engineering against Riot Games: In January 2023, the group was linked with an attack on video game developer Riot Games where social engineering was once again used to access internal systems. This time, the attackers exfiltrated game source code before sending a ransom note [8][9].

Attack on Caesars & MGM: In September 2023, Scattered Spider was linked with attacked on Caesars Entertainment and MGM Resorts International, two of the largest casino and gambling companies in the United States. It was reported that the group gathered nearly six terabytes of stolen data from the hotels and casinos, including sensitive information of guests, and made use of the RaaS strain BlackCat [10].

Ransomware against Marks & Spencer: More recently, in April 2025, the group has also been linked to the alleged ransomware incident against the UK-based retailer Marks & Spencer (M&S) making use of the DragonForce RaaS [11].

How a recent attack observed by Darktrace compares

In May 2025, Darktrace observed a Scattered Spider attack affecting one of its customers. While initial access in this attack fell outside of Darktrace’s visibility, information from the affected customer suggests similar social engineering techniques involving abuse of the customer’s helpdesk and voice phishing (vishing) were used for reconnaissance.

Initial access

It is believed the threat actor took advantage of the customer’s third-party Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) applications, such as Salesforce during the attack.

Such applications are a prime target for data exfiltration due to the sensitive data they hold; customer, personnel, and business data can all prove useful in enabling further access into target networks.

Techniques used by Scattered Spider following initial access to a victim network tend to vary more widely and so details are sparser within OSINT. However, Darktrace is able to provide some additional insight into what techniques were used in this specific case, based on observed activity and subsequent investigation by its Threat Research team.

Lateral movement

Following initial access to the customer’s network, the threat actor was able to pivot into the customer’s Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) environment.

Darktrace observed the threat actor spinning up new virtual machines and activating cloud inventory management tools to enable discovery of targets for lateral movement.

In some cases, these virtual machines were not monitored or managed by the customer’s security tools, allowing the threat actor to make use of additional tooling such as AnyDesk which may otherwise have been blocked.

Tooling in further stages of the attack sometimes overlapped with previous OSINT reporting on Scattered Spider, with anomalous use of Ngrok and Teleport observed by Darktrace, likely representing C2 communication. Additional tooling was also seen being used on the virtual machines, such as Pastebin.

![Cyber AI Analyst’s detection of C2 beaconing to a teleport endpoint with hostname CUSTOMERNAME.teleport[.]sh, likely in an attempt to conceal the traffic.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/68798ca3603c1ac18b3ed3d6_Screenshot%202025-07-17%20at%204.51.51%E2%80%AFPM.avif)

Leveraging LOTL techniques

Alongside use of third-party tools that may have been unexpected on the network, various LOTL techniques were observed during the incident; this primarily involved the abuse of standard network protocols such as:

- SAMR requests to alter Active Directory account details

- Lateral movement over RDP and SSH

- Data collection over LDAP and SSH

Coordinated exfiltration activity linked through AI-driven analysis

Multiple methods of exfiltration were observed following internal data collection. This included SSH transfers to IPs associated with Vultr, alongside significant uploads to an Amazon S3 bucket.

While connections to this endpoint were not deemed unusual for the network at this stage due to the volume of traffic seen, Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst was still able to identify the suspiciousness of this behavior and launched an investigation into the activity.

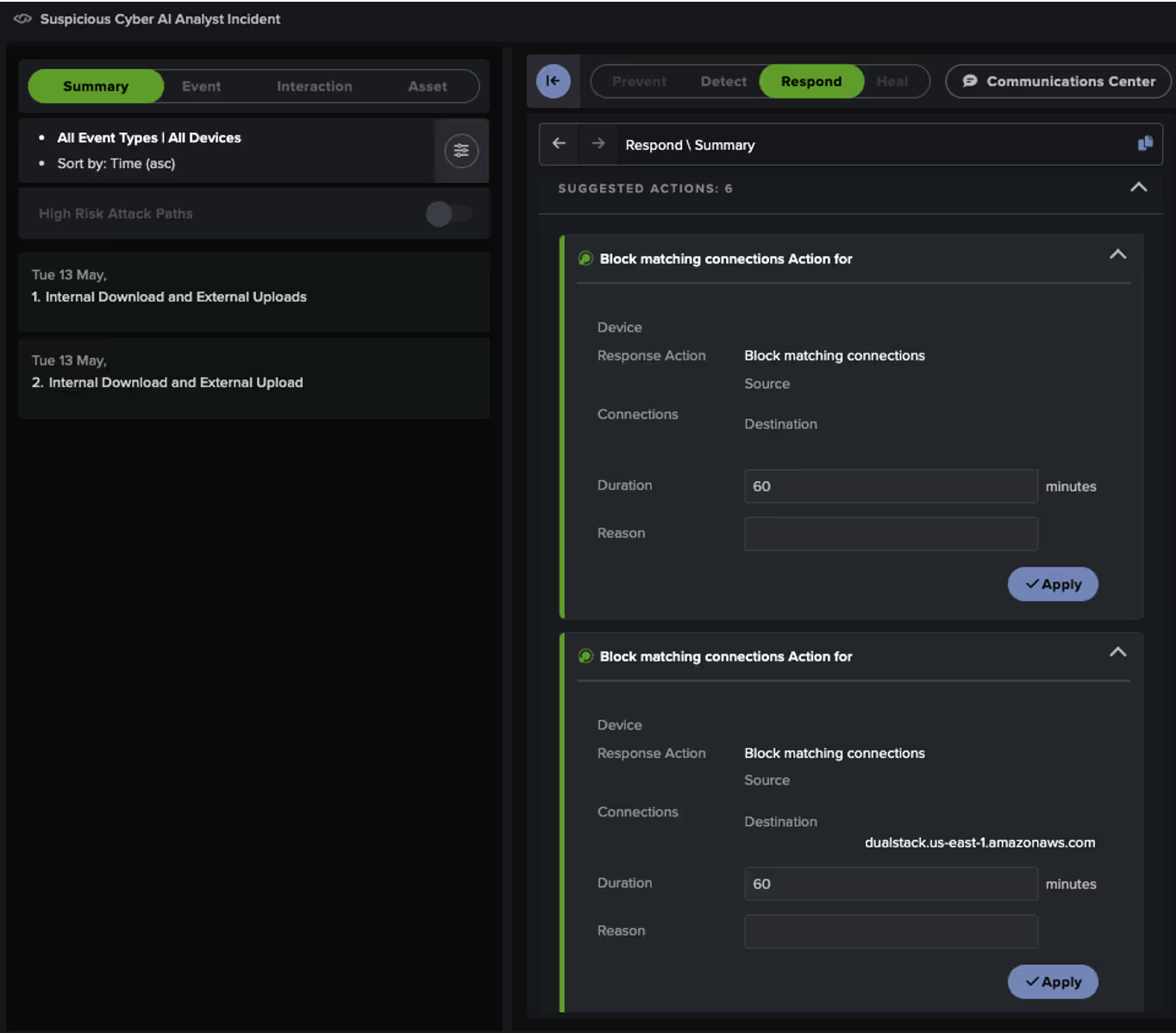

Cyber AI Analyst successfully correlated seemingly unrelated internal download and external upload activity across multiple devices into a single, broader incident for the customer’s security team to review.

Exfiltration and response

Unfortunately, as Darktrace was not configured in Autonomous Response mode at the time, the attack was able to proceed without interruption, ultimately escalating to the point of data exfiltration.

Despite this, Darktrace was still able to recommend several Autonomous Response actions, aimed at containing the attack by blocking the internal data-gathering activity and the subsequent data exfiltration connections.

These actions required manual approval by the customer’s security team and as shown in Figure 3, at least one of the recommended actions was subsequently approved.

Had Darktrace been enabled in Autonomous Response mode, these measures would have been applied immediately, effectively halting the data exfiltration attempts.

Scattered Spider’s use of RaaS

In this recent Scattered Spider incident observed by Darktrace, exfiltration appears to have been the primary impact. While no signs of ransomware deployment were observed here, it is possible that this was the threat actors’ original intent, consistent with other recent Scattered Spider attacks involving RaaS platforms like DragonForce.

DragonForce emerged towards the end of 2023, operating by offering their platform and capabilities on a wide scale. They also launched a program which offered their affiliates 80% of the eventual ransom, along with tools for further automation and attack management [13].

The rise of RaaS and attacker customization is fragmenting TTPs and indicators, making it harder for security teams to anticipate and defend against each unique intrusion.

While DragonForce appears to be the latest RaaS used by Scattered Spider, it is not the first, showcasing the ongoing evolution of tactics used the group.

In addition, the BlackCat RaaS strain was reportedly used by Scattered Spider for their attacks against Caesars Entertainment and MGM Resorts International [10].

In 2024 the group was also seen making use of additional RaaS strains; RansomHub and Qilin [15].

What security teams and CISOs can do to defend against Scattered Spider

The ongoing changes in tactics used by Scattered Spider, reliance on LOTL techniques, and continued adoption of evolving RaaS providers like DragonForce make it harder for organizations and their security teams to prepare their defenses against such attacks.

CISOs and security teams should implement best practices such as MFA, Single Sign-On (SSO), notifications for suspicious logins, forward logging, ethical phishing tests.

Also, given Scattered Spider’s heavy focus on social engineering, and at times using their native English fluency to their advantage, it is critical to IT and help desk teams are reminded they are possible targets.

Beyond social engineering, the threat actor is also adept at taking advantage of third-party SaaS applications in use by victims to harvest common SaaS data, such as PII and configuration data, that enable the threat actor to take on multiple identities across different domains.

With Darktrace’s Self-Learning AI, anomaly-based detection, and Autonomous Response inhibitors, businesses can halt malicious activities in real-time, whether attackers are using known TTPs or entirely new ones. Offerings such as Darktrace /Attack Surface Management enable security teams to proactively identify signs of malicious activity before it can cause an impact, while more generally Darktrace’s ActiveAI Security Platform can provide a comprehensive view of an organization’s digital estate across multiple domains.

Credit to Justin Torres (Senior Cyber Analyst), Emma Foulger (Global Threat Research Operations Lead), Zaki Al-Dhamari (Cyber Analyst), Nathaniel Jones (VP, Security & AI Strategy, FCISO), and Ryan Traill (Analyst Content Lead)

---------------------

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational purposes only and is provided "as is" without any representations or warranties, express or implied. While Darktrace makes reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of the content related to cybersecurity threats such as Scattered Spider, we make no warranties or guarantees regarding the completeness, reliability, or suitability of the information for any purpose.

This blog post does not constitute professional cybersecurity advice, and should not be relied upon as such. Readers should seek guidance from qualified cybersecurity professionals or legal counsel before making any decisions or taking any actions based on the content herein.

No warranty of any kind, whether express or implied, including, but not limited to, warranties of performance, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement, is given with respect to the contents of this post.

Darktrace expressly disclaims any liability for any loss or damage arising from reliance on the information contained in this blog.

Appendices

References

[1] https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-320a

[2] https://attack.mitre.org/groups/G1015/

[3] https://www.rapid7.com/blog/post/scattered-spider-rapid7-insights-observations-and-recommendations/

[6] https://www.cxtoday.com/crm/uk-teenager-accused-of-hacking-twilio-lastpass-mailchimp-arrested/

[7] https://mailchimp.com/newsroom/august-2022-security-incident/

[9] https://www.pcmag.com/news/hackers-behind-riot-games-breach-stole-league-of-legends-source-code

[10] https://www.bbrown.com/us/insight/a-look-back-at-the-mgm-and-caesars-incident/

[11] https://cyberresilience.com/threatonomics/scattered-spider-uk-retail-attacks/

[12] https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/cybersecurity-101/ransomware/ransomware-as-a-service-raas/

[13] https://www.group-ib.com/blog/dragonforce-ransomware/

[14] https://blackpointcyber.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/DragonForce.pdf

[15] https://x.com/MsftSecIntel/status/1812932749314978191?lang=en

Select MITRE tactics associated with Scattered Spider

Tactic – Technique – Technique Name

Reconnaissance - T1598 - Phishing for Information

Initial Access - T1566 – Phishing

Execution - T1204 - User Execution

Privilege Escalation - T1068 - Exploitation for Privilege Escalation

Defense Evasion - T1656 - Impersonation

Credential Access - T1621 - Multi-Factor Authentication Request Generation

Lateral Movement - T1021 - Remote Services

Command and Control - T1102 - Web Service

Command and Control - T1219 - Remote Access Tools

Command and Control - T1572 - Protocol Tunneling

Exfiltration - T1567 - Exfiltration Over Web Service

Impact - T1657 - Financial Theft

Select MITRE tactics associated with DragonForce

Tactic – Technique – Technique Name

Initial Access, Defense Evasion, Persistence, Privilege Escalation - T1078 - Valid Accounts

Initial Access, Persistence - T1133 - External Remote Services

Initial Access - T1190 - Exploit Public-Facing Application

Initial Access - T1566 – Phishing

Execution - T1047 - Windows Management Instrumentation

Privilege Escalation - T1068 - Exploitation for Privilege Escalation

Lateral Movement - T1021 - Remote Services

Impact - T1486 - Data Encrypted for Impact

Impact - T1657 - Financial Theft

Select Darktrace models

Compliance / Internet Facing RDP Server

Compliance / Incoming Remote Access Tool

Compliance / Remote Management Tool on Server

Anomalous File / Internet Facing System File Download

Anomalous Server Activity/ New User Agent from Internet Facing System

Anomalous Connection / Callback on Web Facing Device

Device / Internet Facing System with High Priority Alert

Anomalous Connection / Unusual Admin RDP

Anomalous Connection / High Priority DRSGetNCChanges

Anomalous Connection / Unusual Internal SSH

Anomalous Connection / Active Remote Desktop Tunnel

Compliance / Pastebin

Anomalous Connection / Possible Tunnelling to Rare Endpoint

Compromise / Beaconing Activity to External Rare

Device / Long Agent Connection to New Endpoint

Compromise / SSH to Rare External AWS

Compliance / SSH to Rare External Destination

Anomalous Server Activity / Outgoing from Server

Anomalous Connection / Large Volume of LDAP Download

Unusual Activity / Internal Data Transfer on New Device

Anomalous Connection / Download and Upload

Unusual Activity / Enhanced Unusual External Data Transfer

Compromise / Ransomware/Suspicious SMB Activity

![Pivoting off the previous event by filtering the timeline to events within the same window using timestamp: [“2026-02-18T09:09:00Z” TO “2026-02-18T09:12:00Z”].](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/69a8a18526ca3e653316a596_Screenshot%202026-03-04%20at%201.17.50%E2%80%AFPM.png)