Introduction

Towards the end of March 2022, the operators of Raccoon Stealer announced the closure of the Raccoon Stealer project [1]. In May 2022, Raccoon Stealer v2 was unleashed onto the world, with huge numbers of cases being detected across Darktrace’s client base. In this series of blog posts, we will follow the development of Raccoon Stealer between March and September 2022. We will first shed light on how Raccoon Stealer functioned before its demise, by providing details of a Raccoon Stealer v1 infection which Darktrace’s SOC saw within a client network on the 18th March 2022. In the follow-up post, we will provide details about the surge in Raccoon Stealer v2 cases that Darktrace’s SOC has observed since May 2022.

What is Raccoon Stealer?

The misuse of stolen account credentials is a primary method used by threat actors to gain initial access to target environments [2]. Threat actors have several means available to them for obtaining account credentials. They may, for example, distribute phishing emails which trick their recipients into divulging account credentials. Alternatively, however, they may install information-stealing malware (i.e, info-stealers) onto users’ devices. The results of credential theft can be devastating. Threat actors may use the credentials to gain access to an organization’s SaaS environment, or they may use them to drain users’ online bank accounts or cryptocurrency wallets.

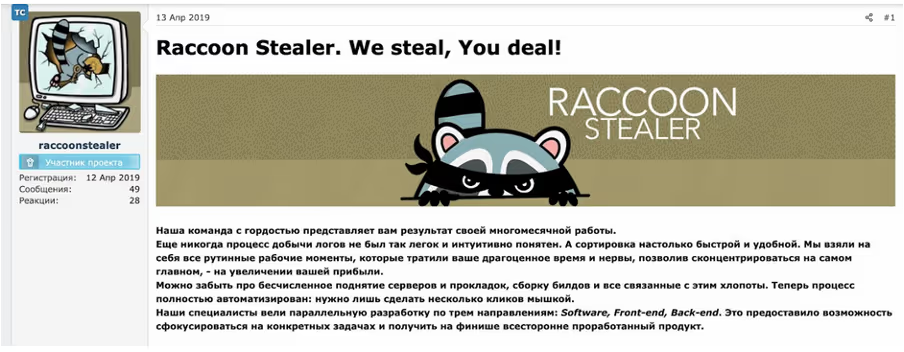

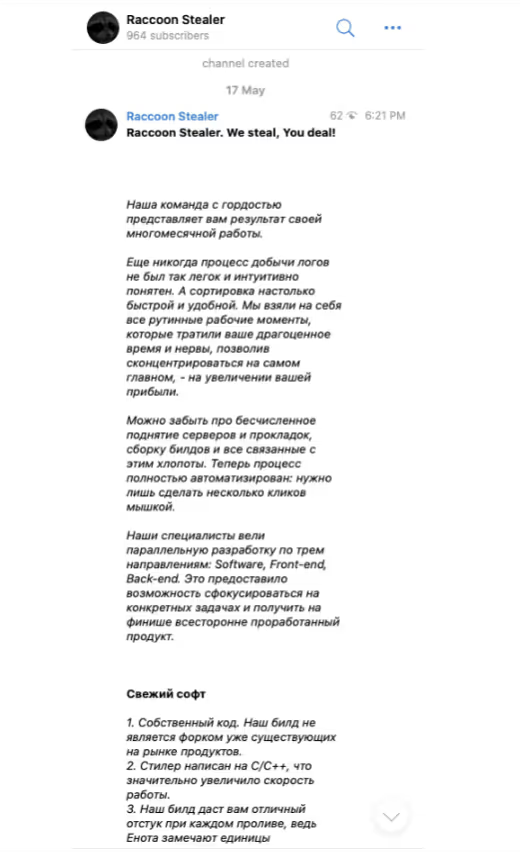

Raccoon Stealer is a Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) info-stealer first publicized in April 2019 on Russian-speaking hacking forums.

The team of individuals behind Raccoon Stealer provide a variety of services to their customers (known as ‘affiliates’), including access to the info-stealer, an easy-to-use automated backend panel, hosting infrastructure, and 24/7 customer support [3].

Once Raccoon Stealer affiliates gain access to the info-stealer, it is up to them to decide how to distribute it. Since 2019, affiliates have been observed distributing the info-stealer via a variety of methods, such as exploit kits, phishing emails, and fake cracked software websites [3]/[4]. Once affiliates succeed in installing Raccoon Stealer onto target systems, the info-stealer will typically seek to obtain sensitive information saved in browsers and cryptocurrency wallets. The info-stealer will then exfiltrate the stolen data to a Command and Control (C2) server. The affiliate can then use the stolen data to conduct harmful follow-up activities.

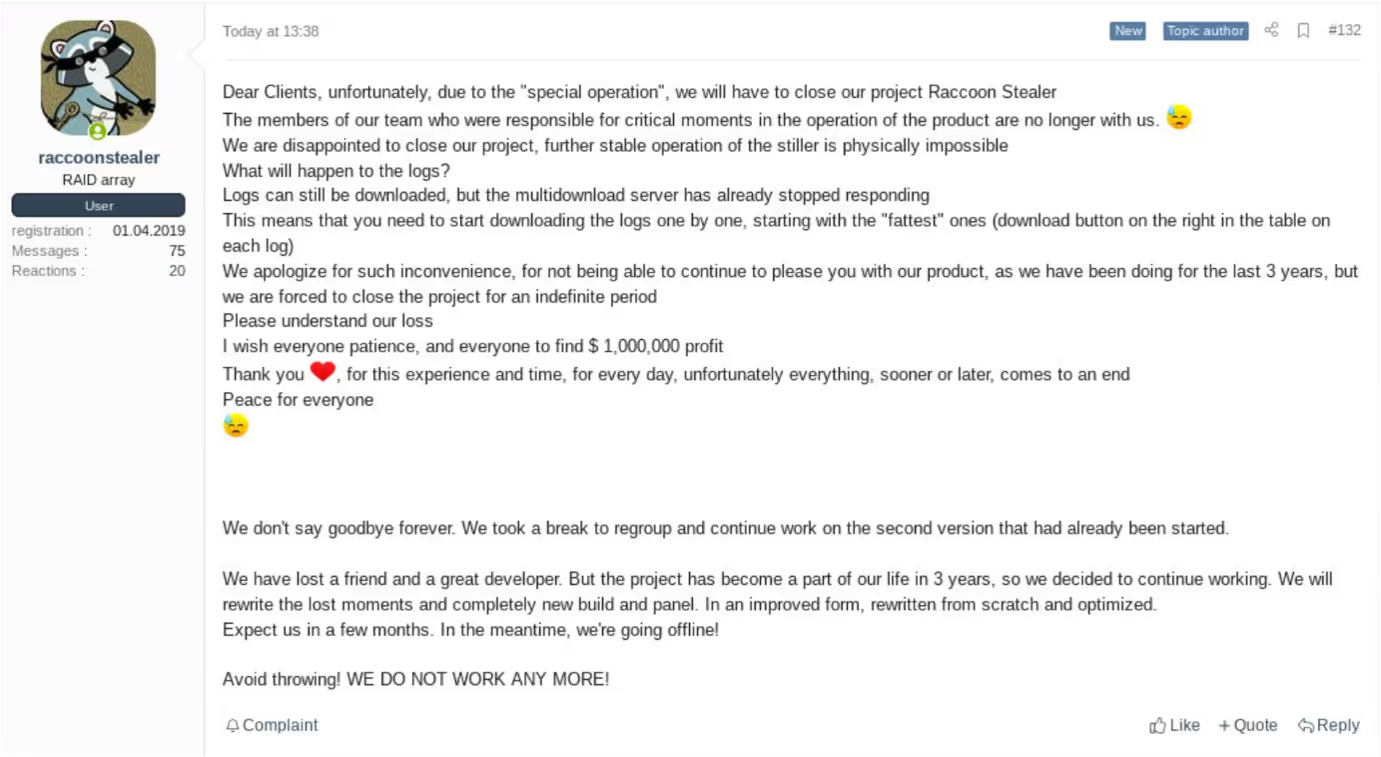

Towards the end of March 2022, the team behind Raccoon Stealer publicly announced that they would be suspending their operations after one of their core developers was killed during the Russia-Ukraine conflict [5].

Recent details shared by the US Department of Justice [6]/[7] indicate that it was in fact the arrest, rather than the death, of a key Raccoon Stealer operator which led the Raccoon Stealer team to suspend their operations [8].

The closure of the Raccoon Stealer project, which ultimately resulted from the FBI-backed dismantling of Raccoon Stealer’s infrastructure in March 2022, did not last long, with the completion of Raccoon Stealer v2 being announced on the Raccoon Stealer Telegram channel on the 17th May 2022 [9].

In the second part of this blog series, we will provide details of the recent surge in Raccoon Stealer v2 activity. In this post, however, we will provide insight into how the old version of Raccoon Stealer functioned just before its demise, by providing details of a Raccoon Stealer v1 infection which occurred on the 18th March 2022.

Attack Details

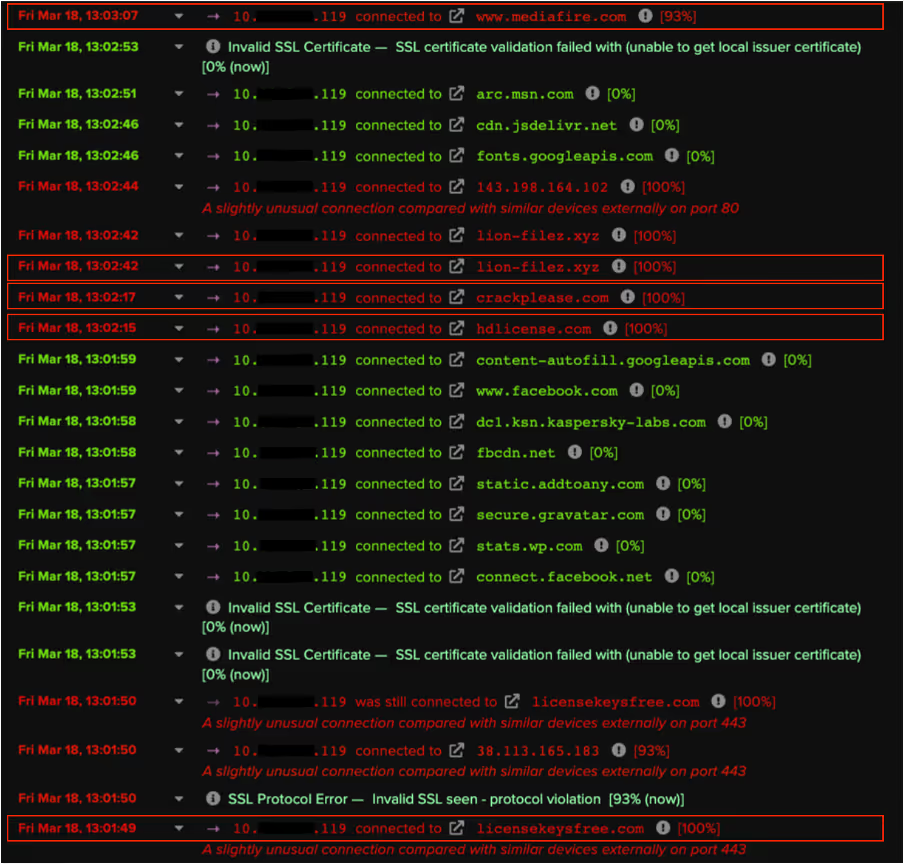

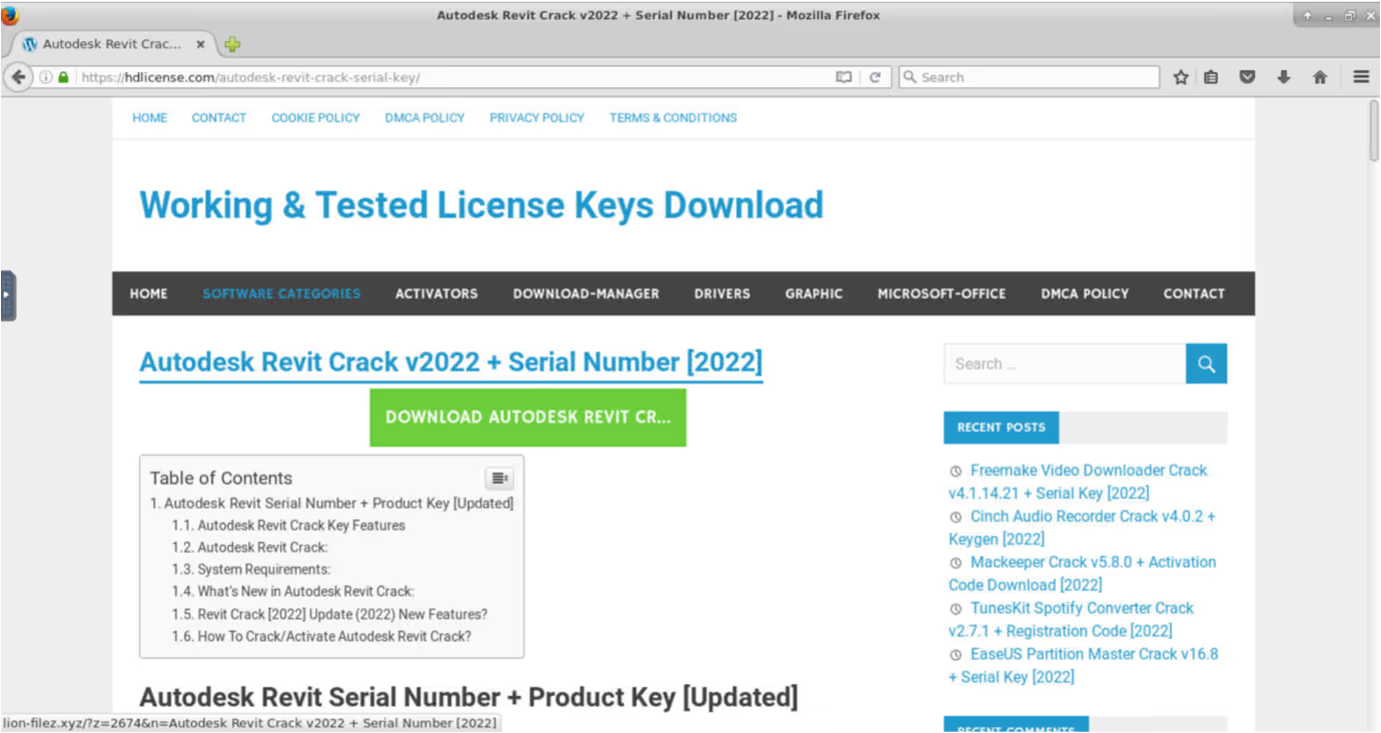

On the 18th March, at around 13:00 (UTC), a user’s device within a customer’s network was seen contacting several websites providing fake cracked software.

The user’s attempt to download cracked software from one of these websites resulted in their device making an HTTP GET request with a URI string containing ‘autodesk-revit-crack-v2022-serial-number-2022’ to an external host named ‘lion-filez[.]xyz’

The device’s HTTP GET request to lion-filez[.]xyz was immediately followed by an HTTPS connection to the file hosting service, www.mediafire[.]com. Given that threat actors are known to abuse platforms such as MediaFire and Discord CDN to host their malicious payloads, it is likely that the user’s device downloaded the Raccoon Stealer v1 sample over its HTTPS connection to www.mediafire[.]com.

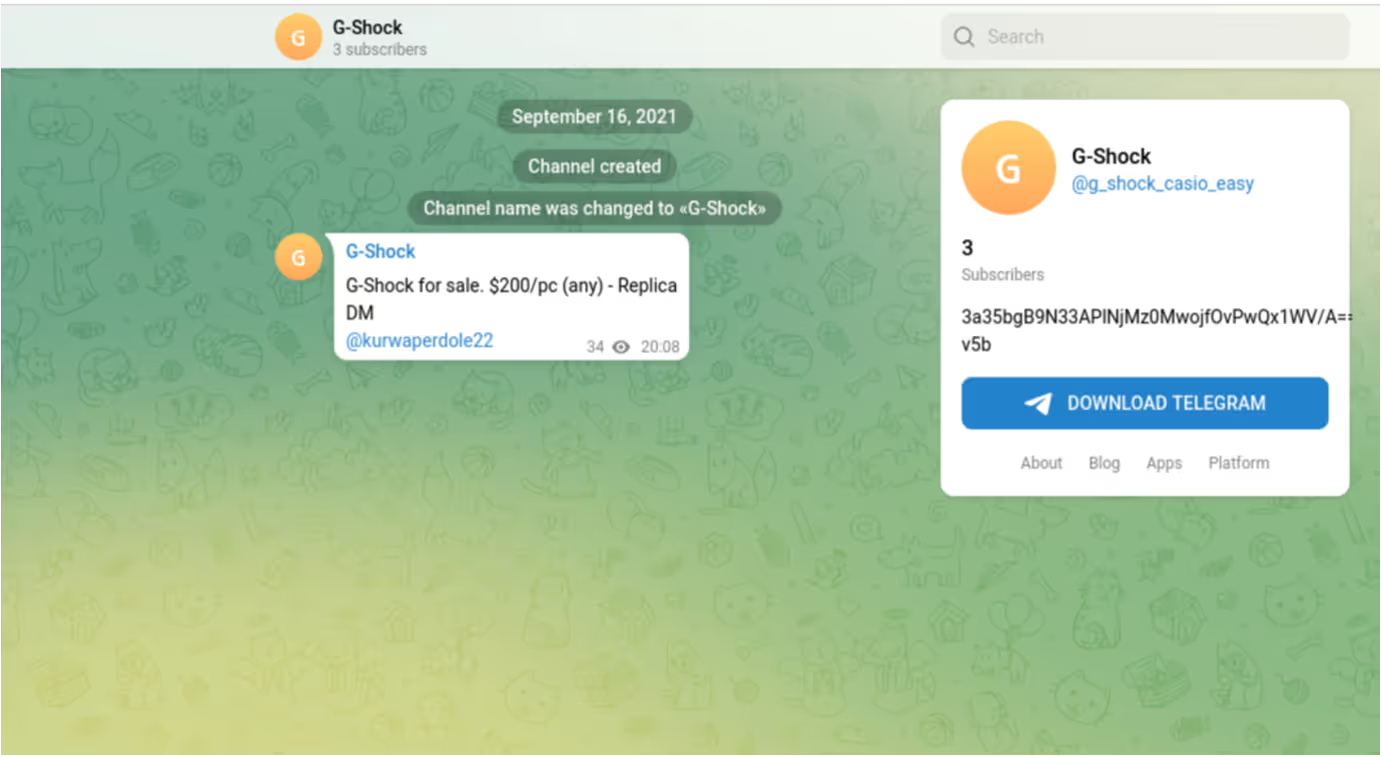

After installing the info-stealer sample, the user’s device was seen making an HTTP GET request with the URI string ‘/g_shock_casio_easy’ to 194.180.191[.]185. The endpoint responded to the request with data related to a Telegram channel named ‘G-Shock’.

The returned data included the Telegram channel’s description, which in this case, was a base64 encoded and RC4 encrypted string of characters [10]/[11]. The Raccoon Stealer sample decoded and decrypted this string of characters to obtain its C2 IP address, 188.166.49[.]196. This technique used by Raccoon Stealer v1 closely mirrors the espionage method known as ‘dead drop’ — a method in which an individual leaves a physical object such as papers, cash, or weapons in an agreed hiding spot so that the intended recipient can retrieve the object later on without having to come in to contact with the source. In this case, the operators of Raccoon Stealer ‘left’ the malware’s C2 IP address within the description of a Telegram channel. Usage of this method allowed the operators of Raccoon Stealer to easily change the malware’s C2 infrastructure.

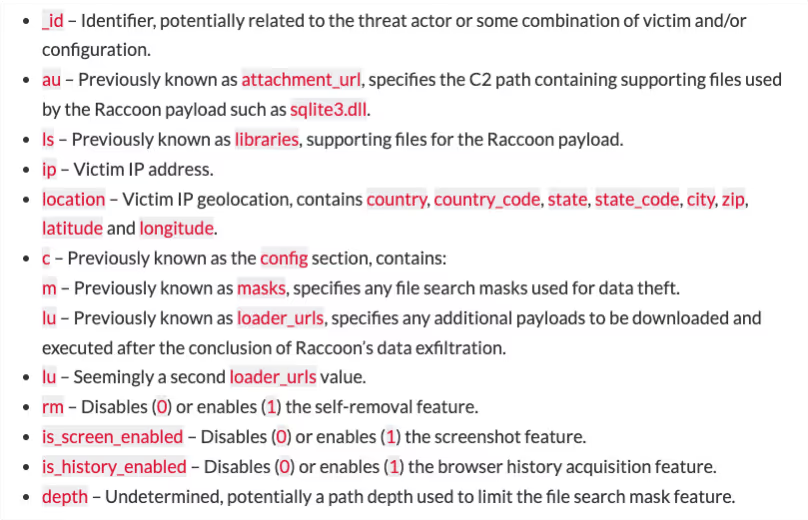

After obtaining the C2 IP address from the ‘G-Shock’ Telegram channel, the Raccoon Stealer sample made an HTTP POST request with the URI string ‘/’ to the C2 IP address, 188.166.49[.]196. This POST request contained a Windows GUID, a username, and a configuration ID. These details were RC4 encrypted and base64 encoded [12]. The C2 server responded to this HTTP POST request with JSON-formatted configuration information [13], including an identifier string, URL paths for additional files, along with several other fields. This configuration information was also concealed using RC4 encryption and base64 encoding.

In this case, the server’s response included the identifier string ‘hv4inX8BFBZhxYvKFq3x’, along with the following URL paths:

- /l/f/hv4inX8BFBZhxYvKFq3x/77d765d8831b4a7d8b5e56950ceb96b7c7b0ed70

- /l/f/hv4inX8BFBZhxYvKFq3x/0cb4ab70083cf5985b2bac837ca4eacb22e9b711

- /l/f/hv4inX8BFBZhxYvKFq3x/5e2a950c07979c670b1553b59b3a25c9c2bb899b

- /l/f/hv4inX8BFBZhxYvKFq3x/2524214eeea6452eaad6ea1135ed69e98bf72979

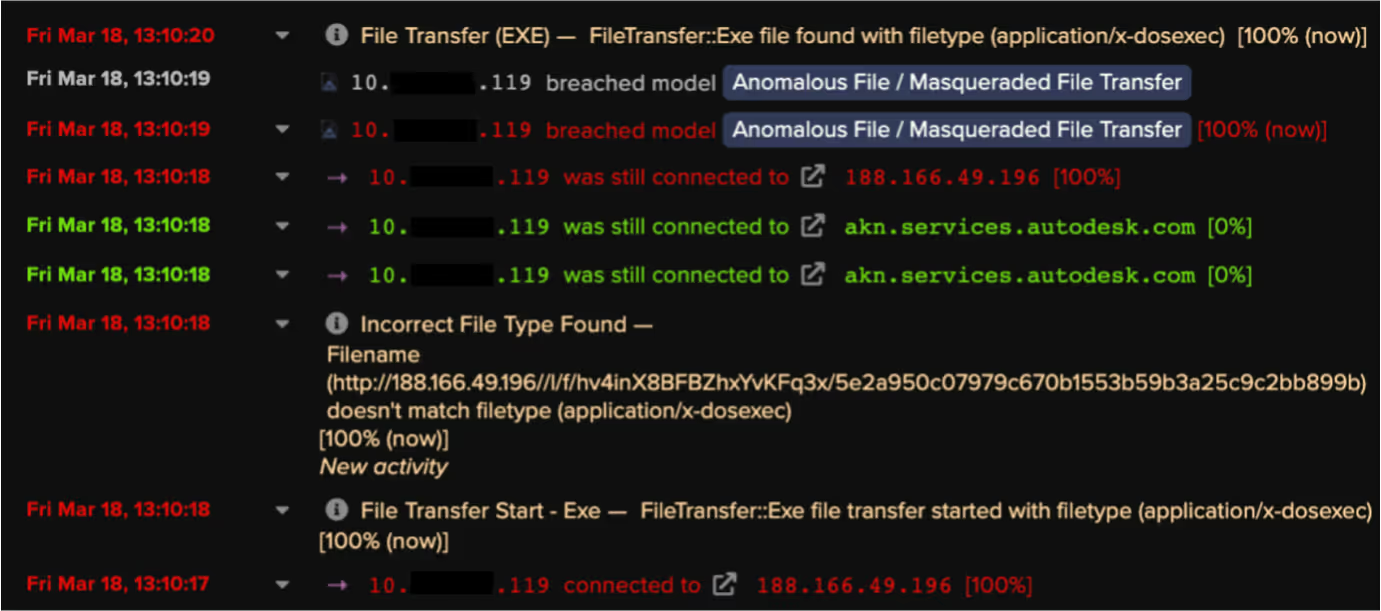

After retrieving configuration data, the user’s device was seen making HTTP GET requests with the above URI strings to the C2 server. The C2 server responded to these requests with legitimate library files such as sqlite3.dll. Raccoon Stealer uses these libraries to extract data from targeted applications.

Once the Raccoon Stealer sample had collected relevant data, it made an HTTP POST request with the URI string ‘/’ to the C2 server. This posted data likely included a ZIP file (named with the identifier string) containing stolen credentials [13].

The observed infection chain, which lasted around 20 minutes, consisted of the following steps:

1. User’s device installs Raccoon Stealer v1 samples from the user attempting to download cracked software

2. User’s device obtains the info-stealer’s C2 IP address from the description text of a Telegram channel

3. User’s device makes an HTTP POST request with the URI string ‘/’ to the C2 server. The request contains a Windows GUID, a username, and a configuration ID. The response to the request contains configuration details, including an identifier string and URL paths for additional files

4. User’s device downloads library files from the C2 server

5. User’s device makes an HTTP POST request with the URI string ‘/’ to the C2 server. The request contains stolen data

Darktrace Coverage

Although RESPOND/Network was not enabled on the customer’s deployment, DETECT picked up on several of the info-stealer’s activities. In particular, the device’s downloads of library files from the C2 server caused the following DETECT/Network models to breach:

- Anomalous File / Masqueraded File Transfer

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Zip or Gzip from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Multiple EXE from Rare External Locations

Since the customer was subscribed to the Darktrace Proactive Threat Notification (PTN) service, they were proactively notified of the info-stealer’s activities. The quick response by Darktrace’s 24/7 SOC team helped the customer to contain the infection and to prevent further damage from being caused. Having been alerted to the info-stealer activity by the SOC team, the customer would also have been able to change the passwords for the accounts whose credentials were exfiltrated.

If RESPOND/Network had been enabled on the customer’s deployment, then it would have blocked the device’s connections to the C2 server, which would have likely prevented any stolen data from being exfiltrated.

Conclusion

Towards the end of March 2022, the team behind Raccoon Stealer announced that they would be suspending their operations. Recent developments suggest that the arrest of a core Raccoon Stealer developer was responsible for this suspension. Just before the Raccoon Stealer team were forced to shut down, Darktrace’s SOC team observed a Raccoon Stealer infection within a client’s network. In this post, we have provided details of the network-based behaviors displayed by the observed Raccoon Stealer sample. Since these v1 samples are no longer active, the details provided here are only intended to provide historical insight into the development of Raccoon Stealer’s operations and the activities carried out by Raccoon Stealer v1 just before its demise. In the next post of this series, we will discuss and provide details of Raccoon Stealer v2 — the new and highly prolific version of Raccoon Stealer.

Thanks to Stefan Rowe and the Threat Research Team for their contributions to this blog.

References

[1] https://twitter.com/3xp0rtblog/status/1507312171914461188

[2] https://www.gartner.com/doc/reprints?id=1-29OTFFPI&ct=220411&st=sb

[3] https://www.cybereason.com/blog/research/hunting-raccoon-stealer-the-new-masked-bandit-on-the-block

[4] https://www.cyberark.com/resources/threat-research-blog/raccoon-the-story-of-a-typical-infostealer

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fsz6acw-ZJY

[8] https://riskybiznews.substack.com/p/raccoon-stealer-dev-didnt-die-in

[9] https://medium.com/s2wblog/raccoon-stealer-is-back-with-a-new-version-5f436e04b20d

[10] https://blog.cyble.com/2021/10/21/raccoon-stealer-under-the-lens-a-deep-dive-analysis/

[11] https://decoded.avast.io/vladimirmartyanov/raccoon-stealer-trash-panda-abuses-telegram/

[12] https://blogs.blackberry.com/en/2021/09/threat-thursday-raccoon-infostealer

[13] https://cyberint.com/blog/research/raccoon-stealer/

Appendices